33 Sinusitis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

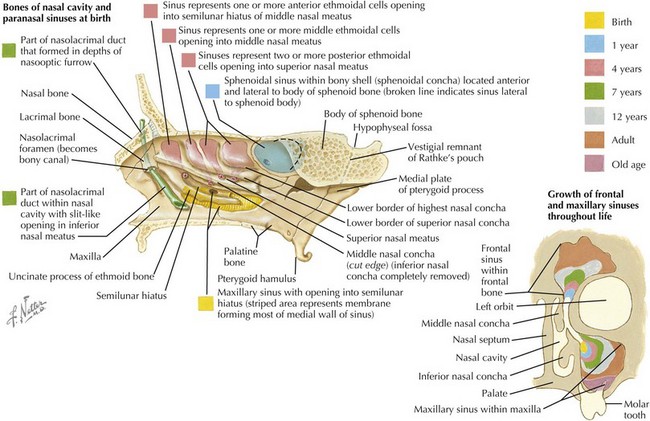

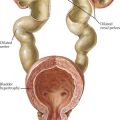

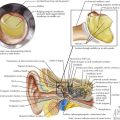

Paranasal sinus development begins in utero and continues until adolescence. The ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are present at birth, although the maxillary sinuses are not pneumatized until approximately 4 years of age. The sphenoid sinus is pneumatized by about 5 years of age. The frontal sinuses are present at 7 to 8 years of age, but they do not fully develop until adolescence (Figure 33-1).

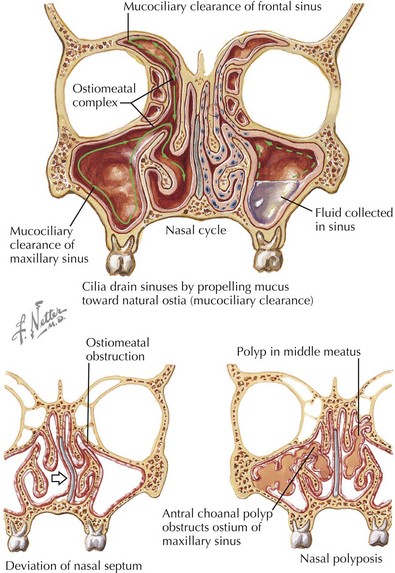

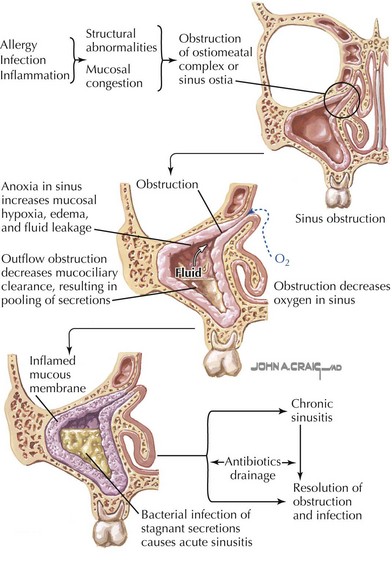

The frontal, anterior ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses drain into the middle meatus of the nasal cavity through the osteomeatal complex. This structure forms a direct communication between the sinuses, which are normally sterile, and the nasopharynx, which is heavily colonized with bacteria. Under normal circumstances, sinus sterility is maintained by the mucociliary apparatus of the sinuses, which mobilizes secretions (and any bacteria that may have entered the sinus cavity) in the direction of the sinus ostia (Figure 33-2). This clearance mechanism may be compromised when the ostia are obstructed (because of mucosal inflammation and swelling, as in viral or allergic rhinitis or mechanical obstruction). The cilia do not function properly, resulting in stasis of secretions and hypoxia, which worsens edema and inflammation and creates an ideal environment for the overgrowth of bacteria (Figure 33-3).

Clinical Presentation

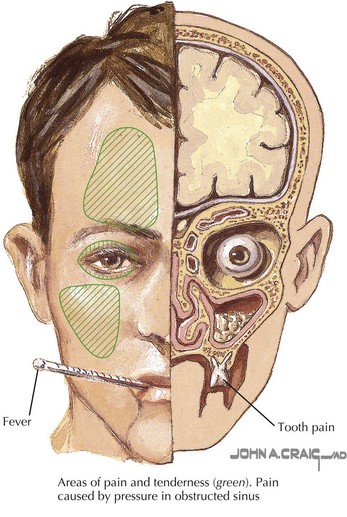

Nasal discharge in ABS is typically consistently purulent and without improvement, in contrast with the nasal discharge in a typical URI, which may become purulent but usually turns clear again before resolving. Nasal congestion or obstruction, fever, and cough (which may be worse at night) are also generally present in URIs but are more persistent in ABS. Halitosis, headache, ill appearance, reproducible facial pain or tenderness, and eye swelling are commonly seen in ABS (Figure 33-4). A thorough physical examination of the nasopharynx may reveal a foreign body, nasal polyps, a deviated septum, or other structures causing mechanical obstruction; more commonly in ABS, mucosal erythema and edema and purulent nasal discharge are seen. Periorbital swelling may be noted. Sinus tenderness may be reproduced over the frontal and maxillary bones, although this sign is difficult to elicit in small children. Transillumination, classically taught to demonstrate the presence of fluid in the sinuses, is also difficult to perform and interpret in children.

Evaluation and Management

Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenko OV, Kovanen N, et al: Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD000243, 2008.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Management of Sinusitis and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: management of sinusitis. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):798-808.

Bluestone CD, Stool SE, Alper CM, et al. Pediatric Otolaryngology, ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003.

Garbutt JM, Goldstein M, Gellman E, Whannon W, Littenberg B. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of antimicrobial treatment for children with clinically diagnosed acute sinusitis. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):619-625.

Wald ER, Chiponis D, Ledesma-Medina J. Comparative effectiveness of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium in acute paranasal sinus infections in children: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1986;77(6):795-800.

Wald ER, Nash D, Eickhoff J. Effectiveness of amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium in the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):9-15.