Chapter 372 Sinusitis

Sinusitis is a common illness of childhood and adolescence with significant acute and chronic morbidity as well as the potential for serious complications. There are 2 types of acute sinusitis: viral and bacterial. The common cold produces a viral, self-limited rhinosinusitis (Chapter 371). Approximately 0.5-2% of viral upper respiratory tract infections in children and adolescents are complicated by acute bacterial sinusitis. Some children with underlying predisposing conditions have chronic sinus disease that does not appear to be infectious. The means for appropriate diagnosis and optimal treatment of sinusitis remain controversial.

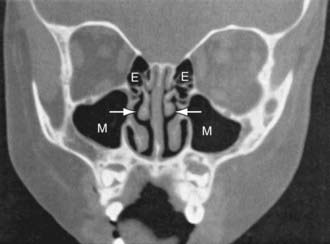

Both the ethmoidal and maxillary sinuses are present at birth, but only the ethmoidal sinuses are pneumatized (Fig. 372-1). The maxillary sinuses are not pneumatized until 4 yr of age. The sphenoidal sinuses are present by 5 yr of age, whereas the frontal sinuses begin development at age 7-8 yr and are not completely developed until adolescence. The ostia draining the sinuses are narrow (1-3 mm) and drain into the ostiomeatal complex in the middle meatus. The paranasal sinuses are normally sterile, maintained by the mucociliary clearance system.

Figure 372-1 Coronal CT scan of normal 3 yr old child. Arrows point to middle meatus. E, ethmoid sinuses; M, maxillary sinuses.

(From Isaacson G: Sinusitis in childhood, Pediatr Clin North Am 43:1297–1317, 1996.)

Etiology

The bacterial pathogens causing acute bacterial sinusitis in children and adolescents include Streptococcus pneumoniae (∼30%; Chapter 176), nontypable Haemophilus influenzae (∼20%; Chapter 186), and Moraxella catarrhalis (∼20%; Chapter 188). Approximately 50% of H. influenzae and 100% of M. catarrhalis are β-lactamase positive. About 25% of S. pneumoniae may be penicillin resistant. Staphylococcus aureus, other streptococci, and anaerobes are uncommon causes of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Although Staphylococcus aureus is an uncommon pathogen for acute sinusitis in children, the increasing prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a significant concern. H. influenzae, α- and β-hemolytic streptococci, M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, and coagulase-negative staphylococci are commonly recovered from children with chronic sinus disease.

Epidemiology

Acute bacterial sinusitis can occur at any age. Predisposing conditions include viral upper respiratory tract infections (associated with out-of-home daycare or a school-aged sibling), allergic rhinitis, and cigarette smoke exposure. Children with immune deficiencies particularly of antibody production (immunoglobulin G [IgG], IgG subclasses, IgA) (Chapter 118), cystic fibrosis (Chapter 395), ciliary dysfunction (Chapter 396), abnormalities of phagocyte function, gastroesophageal reflux, anatomic defects (cleft palate), nasal polyps, cocaine abuse, and nasal foreign bodies (including nasogastric tubes) can develop chronic sinus disease. Immunosuppression for bone marrow transplantation or malignancy with profound neutropenia and lymphopenia predisposes to severe fungal (aspergillus, mucor) sinusitis, often with intracranial extension. Patients with nasotracheal intubation or nasogastric tubes may have obstruction of the sinus ostia and develop sinusitis with the multiple-drug resistant organisms of the intensive care unit (ICU).

Diagnosis

Sinus aspirate culture is the only accurate method of diagnosis but is not practical for routine use for immunocompetent patients. It may be a necessary procedure for immunosuppressed patients with suspected fungal sinusitis. In adults, rigid nasal endoscopy is a less-invasive method for obtaining culture material from the sinus but detects a great excess of positive cultures compared to aspirates. Transillumination of the sinus cavities can demonstrate the presence of fluid but cannot reveal whether it is viral or bacterial in origin. In children, transillumination is difficult to perform and is unreliable. Findings on radiographic studies (sinus plain films, CT scans) including opacification, mucosal thickening, or presence of an air-fluid level are not totally diagnostic (Fig. 372-2). Such findings can confirm the presence of sinus inflammation but cannot be used to differentiate among viral, bacterial, or allergic causes of inflammation.

Treatment

Frontal sinusitis can rapidly progress to serious intracranial complications and necessitates initiation of parenteral ceftriaxone until substantial clinical improvement is achieved (Figs. 372-3 and 372-4). Treatment is then completed with oral antibiotic therapy.

Complications

Because of the close proximity of the paranasal sinuses to the brain and eyes, serious orbital and/or intracranial complications can result from acute bacterial sinusitis and progress rapidly. Orbital complications, including periorbital cellulitis and orbital cellulitis (Chapter 626) are most often secondary to acute bacterial ethmoiditis. Infection can spread directly through the lamina papyracea, the thin bone that forms the lateral wall of the ethmoidal sinus. Periorbital cellulitis produces erythema and swelling of the tissues surrounding the globe, whereas orbital cellulitis involves the intraorbital structures and produces proptosis, chemosis, decreased visual acuity, double vision and impaired extraocular movements, and eye pain. Evaluation should include CT scan of the orbits and sinuses with ophthalmology and otolaryngology consultations. Treatment with intravenous antibiotics should be initiated. Orbital cellulitis can require surgical drainage of the ethmoidal sinuses.

Intracranial complications can include epidural abscess, meningitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, subdural empyema, and brain abscess (Chapter 595). Children with altered mental status, nuchal rigidity, or signs of increased intracranial pressure (headache, vomiting) require immediate CT scan of the brain, orbits, and sinuses to evaluate for the presence of intracranial complications of acute bacterial sinusitis. Treatment with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (usually cefotaxime or ceftriaxone combined with vancomycin) should be initiated immediately, pending culture and susceptibility results. In 50% the abscess is a polymicrobial infection. Abscesses can require surgical drainage. Other complications include osteomyelitis of the frontal bone (Pott puffy tumor), which is characterized by edema and swelling of the forehead (see Fig. 372-3), and mucoceles, which are chronic inflammatory lesions commonly located in the frontal sinuses that can expand, causing displacement of the eye with resultant diplopia. Surgical drainage is usually required.

Ah-See KW, Evans AS. Sinusitis and its management. BMJ. 2007;334:358-361.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Management of Sinusitis and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: management of sinusitis. Pediatrics. 2001;108:798-808.

Arroll B, Kenealy T. Are antibiotics effective for acute purulent rhinitis? Systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo controlled randomized trials. BMJ. 2006;333:279-280.

Coffinet L, Chan KH, Abzug MJ, et al. Immunopathology of chronic rhinosinusitis in young children. J Pediatr. 2009;154:757-758.

Edmondson NE, Parikh SR. Complications of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37(10):680-685.

Esposito S, Principi N, Italian Society of PediatricsItalian Society of Pediatric InfectivologyItalian Society of Pediatric Allergology and ImmunologyItalian Society of Pediatric Respiratory DiseasesItalian Society of Preventive and Social PediatricsItalian Society of OtorhinolaryngologyItalian Society of Chemotherapy; Italian Society of Microbiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and subacute rhinosinusitis in children. J Chemother. 2008;20:147-157.

Germiller JA, Monin DL, Sparano AM, et al. Intracranial complications of sinusitis in children and adolescents and their outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:969-976.

Goldsmith AJ, Rosenfeld RM. Treatment of pediatric sinusitis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2003;50:413-426.

Goytia VK, Giannoni CM, Edwards MS. Intraorbital and intracranial extension of sinusitis: comparative morbidity. J Pediatr. 2011;158:486-491.

Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, et al: Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD006394, 2007.

Kristo A, Uhari M. Timing of rhinosinusitis complications in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:769-771.

Kristo A, Uhari M, Luotonen J, et al. Paranasal sinus findings in children during respiratory infection evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e586-e589.

Lindbaek M, Butler CC. Antibiotics for sinusitis-like symptoms in primary care. Lancet. 2008;371:874-876.

Parikh SR, Brown SM. Image-guided frontal sinus surgery in children. Operative Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;15:37-41.

Piccirillo JF. Acute bacterial sinusitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:902-910.

Slavin RG, Spector RL, Bernstein IL. The diagnosis and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:S13-S47.

Steele RW. Rhinosinusitis in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2006;6:508-512.

Talbot G, Kennedy D, Scheld W, et al. Rigid nasal endoscopy versus sinus puncture and aspiration for microbiologic documentation of acute bacterial maxillary sinusitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1668-1675.

Wald ER, Nash D, Eickhoff J. Effectiveness of amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium in the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:9-15.

Williamson IG, Rumsby K, Benge S, et al. Antibiotics and topical nasal steroid for treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis. JAMA. 2007;298:2487-2496.