Chapter 69B Simple cysts and polycystic liver disease

Surgical and nonsurgical management

Single Cysts

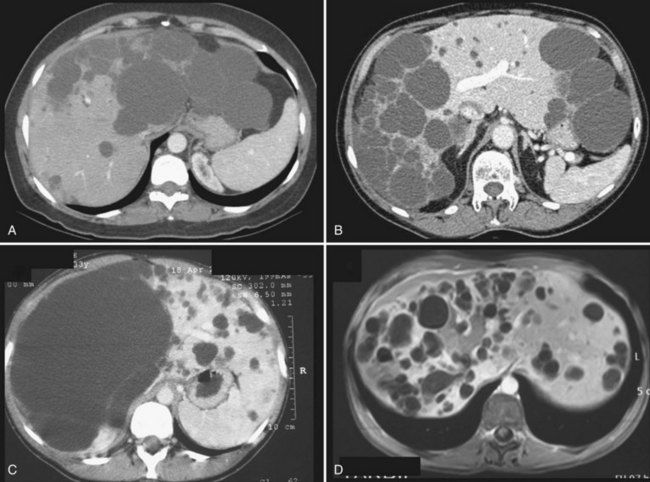

Asymptomatic liver cysts, even when large, need no treatment and do not require surveillance. A small percentage of patients have symptoms related to an increase in the size of cysts (see Chapter 69A). Caution must be exercised when considering whether a simple cyst is symptomatic when it is smaller than 8 cm or when it does not protrude outside of the liver surface. If this is not the case, or if symptoms are vague, ultrasound-guided aspiration of the cyst may be attempted as a therapeutic test. If this does not result in improvement of symptoms, further treatment is not required. When aspiration is effective at relieving symptoms, the cyst is symptomatic. Improvement, however, is transient, as the cyst inevitably recurs after simple aspiration (Saini et al, 1983), and more radical treatment, such as sclerotherapy or fenestration, can be considered.

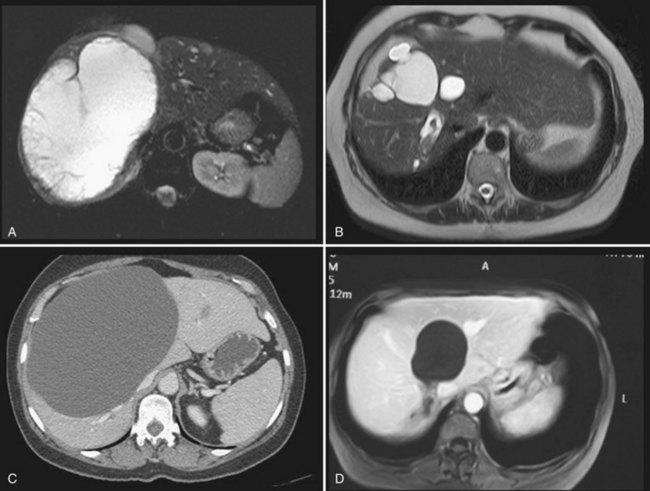

It is unclear whether treatment is indicated in patients who are asymptomatic but nevertheless have evidence on imaging of compression of the bile ducts, or of portal or hepatic veins, by the cysts. If these anomalies are unilateral—that is, at least one hemiliver has normal biliary drainage and normal inflow and outflow—our opinion is that treatment is not required, as the stenosis is not always reversible (Fig. 69B.1).

Sclerotherapy

Method

Sclerotherapy aims at destroying the epithelium lining the inner surface of the wall to stop intracystic fluid secretion (see Chapter 28). Under US guidance, the cyst is located and punctured, and a small drainage catheter is introduced by the Seldinger technique. Injection of water-soluble contrast media ensures that no communication with the bile duct exists and that no leak into the peritoneal cavity is present, both of which are contraindications (Tikkakoski et al, 1996).

The most frequently used sclerosing agent is 95% ethanol, as for renal cysts. Minocycline hydrochloride, otherwise used for pleurodesis or, more recently, ethanolamine oleate (Miyamoto et al, 2006; Nakaoka et al, 2009) have been proposed as alternatives. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has also been performed, although reports are only anecdotal.

The amount of ethanol injected should be limited because alcohol sclerotherapy is associated with an increase in blood alcohol concentration, peaking 3 to 4 hours after treatment (Yang et al, 2006). As massive ethanol intoxication leading to coma has been reported after injection of 240 mL in a 3500 mL cyst (Wernet et al, 2008), the volume of alcohol should not exceed 100 to 120 mL. To ensure that the sclerosant comes in contact with the entire surface, the patient is rolled in different positions. Alcohol is then aspirated and the catheter removed. The procedure is performed with the patient under light general anesthesia because it is painful.

Several protocols have been designed that differ in the duration of alcohol retention in the cyst (from 10 to 240 minutes) and in the number of sessions (single or multiple) (Larssen et al, 2003; Simonetti et al, 1993; Tikkakoski et al, 1996; Yang et al, 2006). Comparative studies are lacking, but a single study showed that 120- and 240-minute retention times yield comparable results (Yang et al, 2006).

Recently, prolonged catheter drainage with negative pressure of the cyst without sclerotherapy has been shown to be as effective as alcohol injection in a randomized study (Zerem, 2009). This result mainly shows that an important aspect of percutaneous treatments in general is to achieve collapse of the cystic cavity.

Complications

Although the injection is painful, pain resolves rapidly and most patients are discharged the following day. Transient neuropsychic disorders secondary to diffusion of alcohol through the cyst wall have been reported. Intracystic bleeding is rare but potentially severe (Fig. 69B.2). It should be realized that vessels are compressed at the periphery of enlarged cysts because of the high intracystic pressure and are therefore not visible; however, bleeding may occur once the cysts have emptied if a vessel has been inadvertently punctured.

Long-Term Outcome

A systematic literature review published in 2001 identified 112 patients treated by alcohol sclerotherapy and 17 treated with minocycline hydrochloride instillation (Moorthy et al, 2001). In most patients, a complete or partial regression of the cyst was seen, but follow-up was short overall. Although the reported experience since then has been limited, the efficacy has been confirmed, with a symptomatic recurrence rate requiring additional treatment of less than 5% (Erdogan et al, 2007).

An early morphologic assessment, usually by US, is frequently performed. However, patients should be warned that this is likely to show the persistence of the cyst, although at a smaller size; this is not predictive of symptomatic recurrence. In practice, several months—perhaps up to a year—may be required to achieve optimal efficacy after alcohol sclerotherapy (Fig. 69B.3).

Fenestration

Limitations

Cysts protruding into segments VII or VIII are not formal contraindications to laparoscopic fenestration, but the procedure is unlikely to be very successful in such a case because limited access will prevent wide unroofing. In addition, the margins of the opening may adhere to the diaphragm, and the risk of cyst recurrence is increased as a result of contained secretion (Fig. 69B.4). Open fenestration is a wise alternative in this circumstance.

Complications

The most severe intraoperative complication is bleeding, and transfusion has occasionally been required (Loehe et al, 2010). This occurs when the liver parenchyma, not the cyst wall, is opened. Conversion, the most frequent indication for which is bleeding, is required in less than 5% of patients.

Postoperative complications are rare, and patients are usually discharged after 1 to 3 days. No deaths have been reported, and morbidity ranges between 0% and 15% (Gall et al, 2009; Loehe et al, 2010). The most severe complications include biliary leak and hemorrhage, which result from reexpansion of biliary and vascular structures that were compressed at the interface between the cyst wall and the parenchyma and that were inadequately secured. If the periphery of the opened cyst is thick, it should be closed with running sutures; an alternative is to use an endovascular stapler on these portions of the cyst wall because it allows wide fenestration while maintaining hemostasis. Ascites is very rare after fenestration of simple cysts, unlike PCLD (see below).

Long-Term Outcome

Long-term efficacy of fenestration for simple cysts is still somewhat unclear. Reported experience is limited, follow-up is usually short, and results are not always stratified according to the number of cysts (i.e., simple cysts vs. PCLD). Furthermore, cyst recurrence, symptomatic recurrence, and the need for additional treatment are not always distinguished. It is usually assumed that although cysts may recur in one third to one half of patients, symptomatic recurrence occurs in less than 5% (Hansman et al, 2001; Morino et al, 1994; Tan et al, 2005); however, higher figures of symptomatic recurrence (15% to 20%) have been reported (Erdogan et al, 2007; Gall et al, 2009; Martin et al, 1998).

A more precise comparison of preoperative and postoperative symptoms has recently been published (Loehe et al, 2010). Abdominal pain was improved in 91% of patients and disappeared in 68%. Other symptoms—including impaired gastrointestinal transport, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, and acid reflux—disappeared in 53% of the patients. Overall, within 1 year of surgery, 32% of the patients developed or had persistent subjective symptoms in this series, but this rate decreased to 7% and 2% after 3 and 5 years, respectively. During follow-up, 9% required reoperation.

Persistent symptoms may be related to technical failure or reflect inaccurate selection, with some patients undergoing surgery for non–cyst-related symptoms (see Chapter 69A).

Sclerotherapy Versus Fenestration

Although both techniques have been used for years, no randomized or prospective comparative analysis has been done. As a rule, the severity of symptoms that leads to treatment has not been standardized, and recurrence is poorly defined. It would seem that both methods are almost as effective (Erdogan et al, 2007; Furuta et al, 1990; Moorthy et al, 2001). Our policy is to systematically attempt sclerotherapy first; fenestration is indicated in cases of recurrence, but location of the protruding part of the cyst may influence this choice (see Fig. 69B.4).

Polycystic Liver Disease

Symptoms in PCLD are related mainly to the volume of the entire liver rather than to the volume of a specific cyst. Although palliation with percutaneous alcohol sclerotherapy or laparoscopic fenestration has been reported, neither proves effective in the long term in the most frequent forms of PCLD (Robinson et al, 2005). The aim of treatment is instead to decompress and reduce the size of the entire liver or to remove as many cysts as possible. In highly symptomatic patients, these objectives can be achieved by open fenestration, liver resection, or liver transplantation. Patients should be carefully informed of the limitations and risks of these procedures. Medical alternatives have been recently introduced, although larger studies are required to confirm their clinical impact.

Nonsurgical Treatments

Medical Treatment

Avoidance of Estrogen Replacement Therapy

Avoidance of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) would seem logical as medical treatment for PCLD because hepatic cystic disease may worsen under the influence of hormones of pregnancy or exogenous female steroid hormones (Shrestha et al, 1997). However, proof that avoidance is effective is lacking, and the benefits and drawbacks should be discussed on an individual basis.

Somatostatin Analogues

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is a potent mediator of cholangiocyte proliferation and secretion of fluid into cysts (see Chapter 69A). Somatostatin receptors are expressed on cholangiocytes; when triggered, this activates a signaling cascade that suppresses cAMP. Somatostatin blunts hepatic cyst expansion by blocking secretin-induced cAMP generation (Masyuk et al, 2007). It also suppresses the expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and other cystogenic growth factors and downstream signaling from their receptors (Pyronnet et al, 2008). Two randomized controlled trials have recently demonstrated that 6 or 12 months of treatment with lanreotide, a long-acting somatostatin analogue, was associated with a significant reduction of liver volume in patients with PCLD, with or without autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), compared with placebo-treated controls (Hogan et al, 2010; van Keimpema et al, 2009). This was especially the case in patients with larger livers; however, this decrease in volume was limited overall, on average 3% to 5%. Severity of abdominal symptoms was not improved (Van Keimpema et al, 2009), although some features of quality of life scores were.

mTOR Inhibitors

Although mTOR-mediated signaling has been shown to play a role in cyst expansion (see Chapter 69A), sirolimus inhibits this pathway and promotes apoptosis. Follow-up of transplant recipients with ADPKD whose immunosuppression contained sirolimus has shown that both the native kidney (Shillingford et al, 2006) and liver volume (Qian et al, 2008) decreased compared with those of patients who received the more classic calcineurin inhibitor immunosuppression. The clinical impact of this size reduction was not assessed. Trials have been lauched in ADPKD patients to halt the progression of kidney disease (Perico et al, 2010), but long-term efficacy and safety studies are required. This treatment should not be used outside these trials.

Arterial Embolization

Transcatheter embolization, also known as renal contraction therapy, has been advocated in Japan since the mid-1990s for patients with ADPKD (Ubara et al, 2002), and it has been applied to PCLD since the early 2000s (Takei et al, 2007). The rationale is that kidney cysts are supplied by well-developed arteries, but hepatic cysts in ADPKD patients are mostly supplied from hepatic arteries but not from portal veins. Embolization may use microcoils or polyvinyl alcohol particles, ranging in size between 150 and 250 µm, and targets hepatic artery branches supplying the hepatic segments mainly replaced by the cysts (Park et al, 2009;Takei et al, 2007). Considering the extent of the disease and the number of small-branch arteries to occlude, the procedure is demanding. Reported experience is limited, but the largest series includes 30 patients in whom intrahepatic cyst volume was significantly reduced (from 6.667 ± 2.978 cm3 to 4.625 ± 2.299 cm3), whereas the volume of hepatic parenchyma increased (Takei et al, 2007). Improvement of symptoms was observed in most patients but required several months to be optimal. No major complications were related except for classic but occasionally severe postembolization syndrome (Takei et al, 2007; Park et al, 2009). Because targeted segments are those that also have an occluded portal flow, it is possible that the procedure acts as a hepatectomy, favoring regeneration of noncystic parenchyma.

Cyst-Targeted Treatments

Percutaneous Sclerotherapy

Percutaneous sclerotherapy is usually considered ineffective in patients with PCLD because symptoms are related to the multiplicity of the cysts, which cannot all be targeted. Furthermore, the rigid architecture of the parenchyma, as well as the presence of smaller adjacent cysts, prevents cyst collapse. Symptomatic recurrence requiring additional treatment occurs in most patients (Erdogan et al, 2007); however, a small subset of patients have one or a few strategically located large cysts (>6 cm) that may account for at least part of the symptoms and can be managed as simple cysts (see Fig. 69B.3). The technique and results do not differ from those for simple cysts. Cyst resolution is gradual and may only be optimum within 1 year of therapy.

Fenestration

Technique and Indication

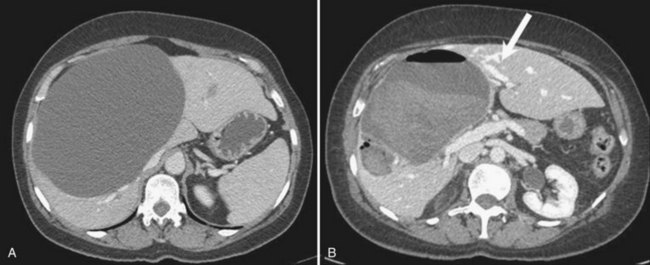

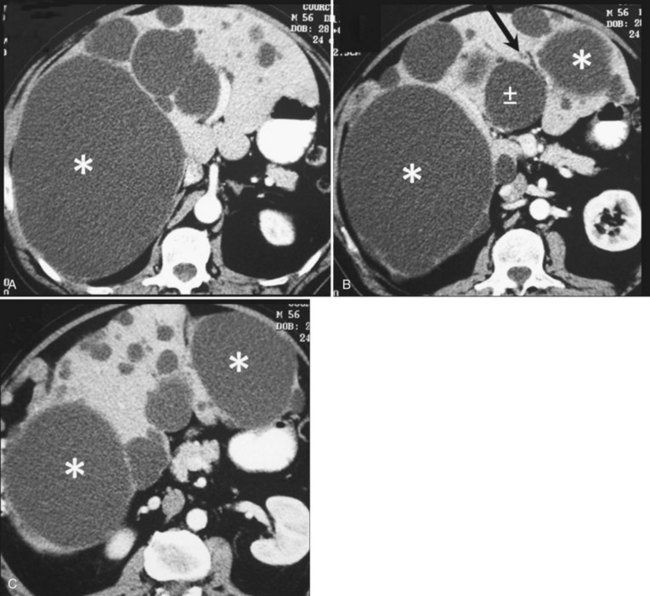

Initially described by Lin and colleagues (1968), the aim of fenestration is to unroof as many cysts as possible, starting with superficial cysts and proceeding stepwise to the deeper cysts. Open fenestration was historically the standard therapy, but a laparoscopic approach has also been used recently; with few exceptions, this does not allow sufficient and safe access to the deeper cysts and, as a rule, a laparoscopic approach is contraindicated (Kabbej et al, 1996; Morino et al, 1994). The exceptions are patients with a limited number of large and superficial cysts that can be individually treated as single cysts (Fig. 69B.5).

Complications

Fenestration for PCLD is associated with a higher incidence of postoperative biliary leak compared with fenestration for simple cysts. This occurs particularly when cysts are left untreated around the biliary confluence (Fig. 69B.6). Performing intraoperative cholangiography to ensure that biliary drainage of both hemilivers is normal at the end of the procedure is advisable.

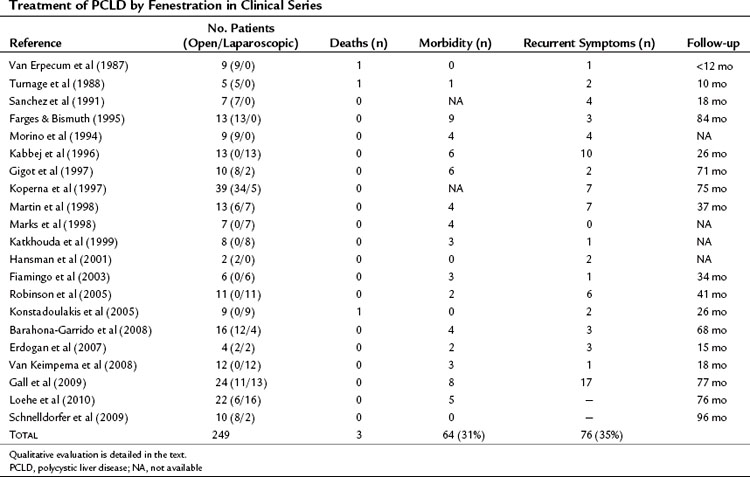

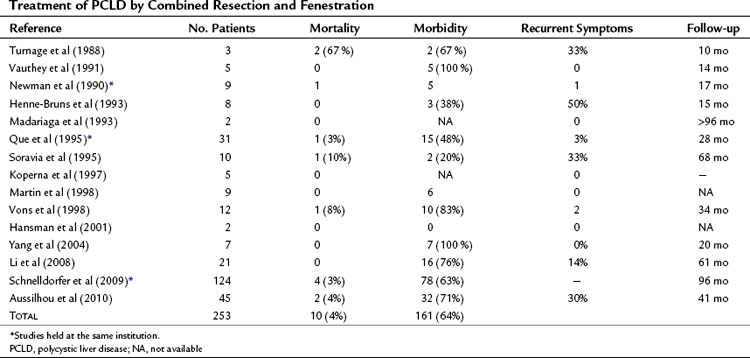

Mortality, although at low rates, has been reported, and morbidity averages 31% (Table 69B.1).

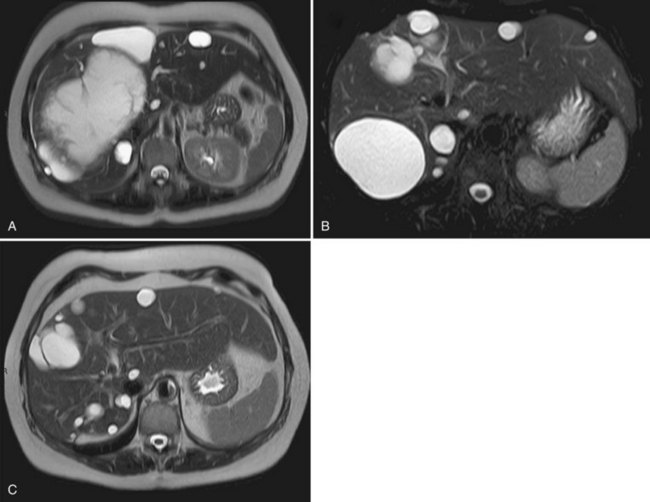

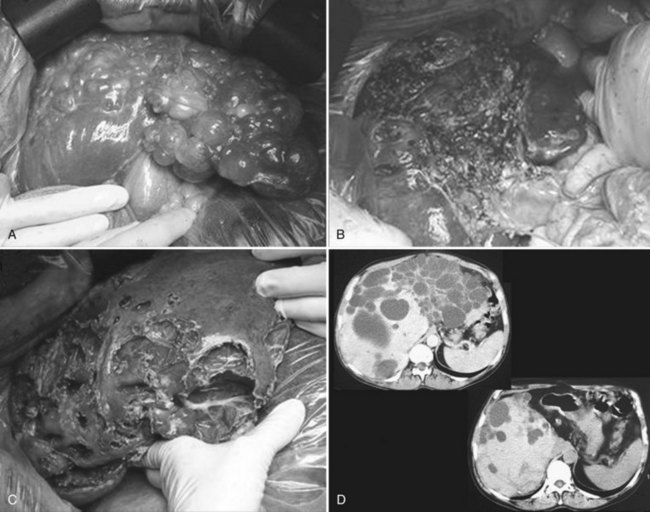

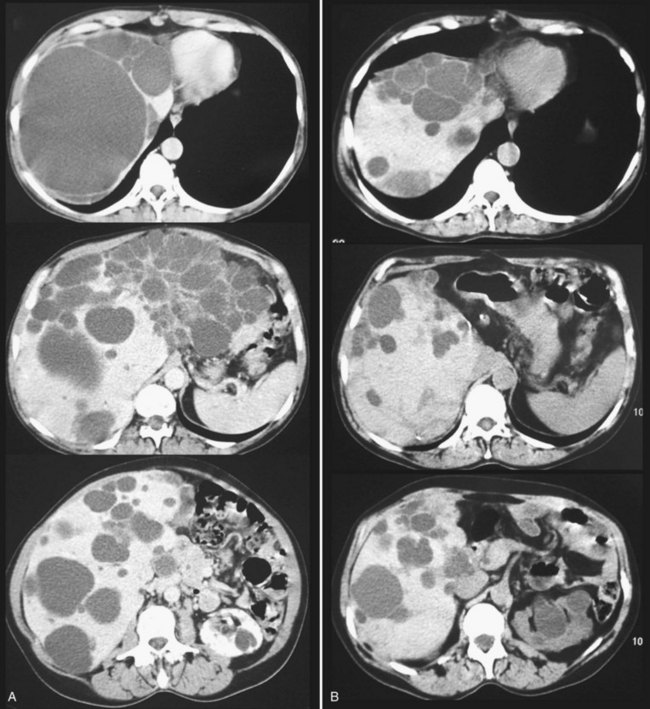

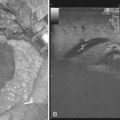

Hepatectomy

Partial liver resection has been proposed, in combination with fenestration of the remnant liver, to reduce liver volume and increase regeneration of the noncystic liver (Que et al, 1995). This is made possible by the frequently asymmetric distribution of the cysts, with some areas being relatively spared (Fig. 69B.7). Regeneration is associated with expansion of these areas, whereas the volume of the remaining small cysts remains unchanged or progresses very slowly. Although this technique is highly successful in some patients, it is technically demanding, associated with a high morbidity rate, and its indications are becoming more selective and restrictive.

Technique

After hepatectomy, the remnant liver is widely fenestrated (see Fig. 69B.7). Intraoperative cholangiography may be advisable to ensure that no bile duct injury has occurred and that bile drains freely (i.e., that a deeply situated cyst does not compress the remnant right or left duct). Considering the high rate of biliary leak, a leakage test should also be performed; it is also wise to place running sutures along the transected cyst walls. After right-sided resections, care should be taken to secure the remnant liver in a stable position, resulting in adequate venous outflow. A suction drain is frequently left in the abdomen.

Morbidity and Mortality

Hepatectomy for PCLD, although a benign disease, is a demanding procedure with a definite risk of mortality and high morbidity rates, even when performed by highly experienced hepatopancreatobiliary surgeons. The main intraoperative risk is that of bleeding; and perioperative transfusions are required in 50% to 80% of the patients. Injury to the main bile duct within the liver remnant occurs in 5% (Aussilhou et al, 2010; Schnelldorfer et al, 2009).

Mortality rates in the literature average 4% (Table 69B.2) and has been related to abdominal sepsis, acute Budd-Chiari syndrome, and complications related to treatment of complications. Intracranial hemorrhage from ruptured aneurysms have also been described (see Chapter 69A).

Morbidity rates average 64% (see Table 69B.2), but some consider that it is virtually constant. The most frequent complications are ascites and pleural effusion, and the mechanism is likely the same as for fenestration: persistent fluid secretion by the remnant epithelial lining and relative outflow obstruction. However, increased portal pressure and lymphatic leakage associated with liver resection increase this risk. Furthermore, patients undergoing liver resection, rather than fenestration tend to have more severe PCLD with malnutrition. Although ascites resolves in most patients within 1 month, some have required stenting of the inferior vena cava or hepatic veins to resolve outflow obstruction (Grams et al, 2007; Schnelldorfer et al, 2009). The next most frequent complications are hemorrhage and biliary leak; approximately 10% of patients require reoperation for management of these. In contrast, liver failure is infrequent. Hepatectomy is usually not performed in patients with severe kidney failure. In those with moderate impairment, although a slight transient deterioration of kidney function may be observed, most patients have recovered their preoperative creatinine levels by the time of discharge.

Preoperative risk factors for complications include kidney dysfunction, ascites, and denutrition (Schnelldorfer et al, 2009). In the presence of these symptoms, liver transplantation is indicated.

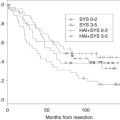

Long-Term Outcome

Results are highly variable among series and among patients. This reflects the diversity of the clinical and morphologic situations as well as the extent of resection. The average reduction in hepatic volume achieved ranges between 50% and 75% (Aussilhou et al, 2010; Schnelldorfer et al, 2009), which results in considerable objective and subjective improvement in more than 75% of the patients (Fig. 69B.8). Symptoms may recur because of the enlargement of some cysts that were left untreated, and such patients may benefit from targeted treatments, sclerotherapy in particular. In addition, other recurrences are related to the progressive reexpansion of the entire liver. It has recently been estimated that after 4 years of follow-up, the liver was on average 11% larger than the initial remnant volume after resection (Schnelldorfer et al, 2009). However, half of the patients have stable volumes, a difference that may also reflect the variable natural history of the disease.

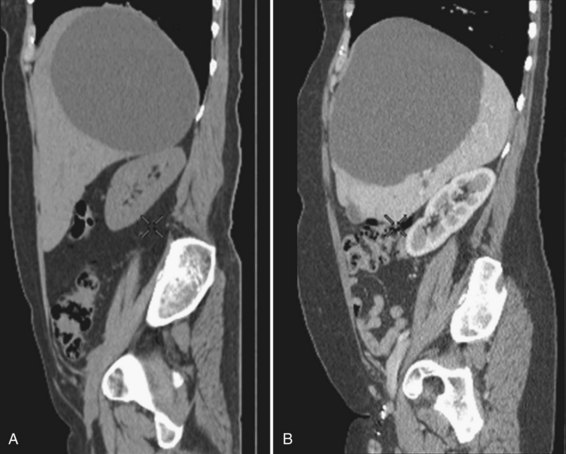

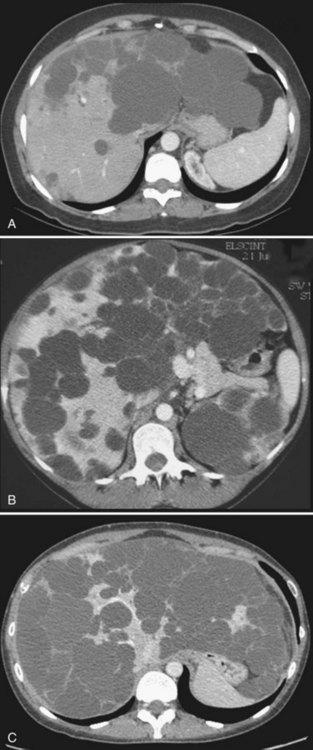

Transplantation

Because PCLD is a genetic disease, liver transplantation is the only curative treatment (see Chapter 97A). As for any benign disease, there is some reluctance to perform this high-risk procedure for this indication, considering that liver function is preserved. However, some patients with massive liver involvement have incapacitating symptoms that may be life threatening (ascites, denutrition); in this situation, and when liver resection is considered too high risk with little anticipated efficacy, liver transplantation is the only option (Fig. 69B.9). Quality of life is excellent after transplantation despite the need for long-term immunosuppression.

In countries where graft allocation is patient oriented, based on Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) criteria, exceptions have been implemented because patients with PCLD who do not have liver failure would otherwise have no chance to undergo transplantation (Arrazola et al, 2006).

Technique

Most transplantations have been performed with livers from brain-dead donors, although living donors have also been used (Mekeel et al, 2008). The technique is the same as that for other indications, but, as for hepatectomy, extensive fenestration is required first to gain access to the liver. The inferior vena cava can be preserved, which is important in the context of living donation, but transient clamping may be necessary to achieve this. A transient portocaval shunt is required in most instances because PCLD does not induce portal hypertension with spontaneous portosystemic shunts.

In patients with ADPKD (see Chapter 69A), simultaneous kidney transplantation is not necessary if the glomerular filtration rate is more than 60 mL/min (Martin et al, 2008) but is indicated if it is less than 30 mL/min. For values between 30 and 60 mL/min, single liver transplantation appears safe, provided renal-sparing immunosuppression is used. Secondary kidney transplantation may be required in half of the patients with the drawback of previous immunization through liver transplantation (Jeyarajah et al, 1998; Pirenne et al, 2001; Ueno et al, 2006).

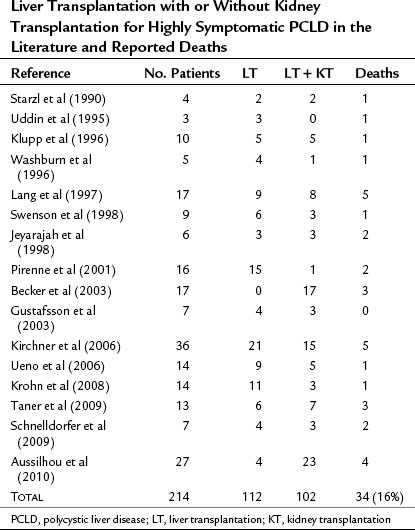

Perioperative Risk

Liver transplant for PCLD is also technically demanding, particularly in patients who have undergone previous procedures. Virtually all patients require an intraoperative transfusion. Reported mortality rate is 16% overall (Table 69B.3) and is mainly related to sepsis. As for other indications of transplantation, perioperative mortality and morbidity, in particular from sepsis, are increased in patients with the most severe forms of the disease. Such severe forms are usually associated with malnutrition (Lang et al, 1997; Pirenne et al, 2001).

Long-Term Outcome

The 5-year survival rate in the registries is 80% to 84%, higher than for most other indications. Quality of life is excellent (Kirchner et al, 2006), and short- and long-term results are the same for liver transplantation as for combined transplantation of liver and kidney.

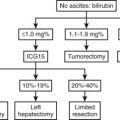

Choice of Surgical Treatment

PCLD covers a wide range of morphologic and clinical situations (see Chapter 69A), and three classifications have been proposed to help the clinician chose among the various treatment options. One classification was designed to identify under which circumstances fenestration of PCLD is indicated (Gigot et al, 1997). The two others have more recently aimed at defining the limits of resection (Li et al, 2008; Schnelldorfer et al, 2009), but all three classifications overlap to some degree (Fig. 69B.10).

Although the natural history of PCLD is highly variable among patients, progression is fairly linear for any given patient (see Chapter 69A). Therefore age at the time of diagnosis, first symptoms, incapacitating symptoms, and kidney involvement are useful markers to predict the future need for transplantation. When transplantation will likely be indicated at some stage of the disease, fenestration and resection should be considered with caution to avoid increasing the risks of transplantation.

Arrazola L, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception for polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:S110-S111.

Aussilhou B, et al. Extended liver resection for polycystic liver disease can challenge liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2010;252:735-743.

Barahona-Garrido J, et al. Factors that influence outcome in non-invasive and invasive treatment in polycystic liver disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3195-3200.

Becker T, et al. Results of combined and sequential liver-kidney transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1067-1078.

Erdogan D, et al. Results of percutaneous sclerotherapy and surgical treatment in patients with symptomatic simple liver cysts and polycystic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3095-3100.

Farges O, Bismuth H. Fenestration in the management of polycystic liver disease. World J Surg. 1995;19:25-30.

Fiamingo P, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of simple hepatic cysts and polycystic liver disease. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:623-626.

Furuta T, et al. Treatment of symptomatic non-parasitic liver cysts: surgical versus alcohol injection therapy. HPB Surgery. 1990;2:269-277.

Gall TM, et al. Surgical management and long-term follow-up of non-parasitic hepatic cysts. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:235-241.

Gigot JF, et al. Adult polycystic liver disease: is fenestration the most adequate operation for long-term management? Ann Surg. 1997;225:286-294.

Grams J, et al. Inferior vena cava stenting: a safe and effective treatment for intractable ascites in patients with polycystic liver disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:985-990.

Gustafsson BI, et al. Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease: indications and outcome. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:813-814.

Hansman MF, et al. Management and long-term follow-up of hepatic cysts. Am J Surg. 2001;181:404-410.

Henne-Bruns D, Klomp HJ, Kremer B. Non-parasitic liver cysts and polycystic liver disease: results of surgical treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:1-5.

Hogan MC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1052-1061.

Jeyarajah DR, et al. Liver and kidney transplantation for polycystic disease. Transplantation. 1998;66:529-532.

Kabbej M, et al. Laparoscopic fenestration in polycystic liver disease. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1697-1701.

Katkhouda N, et al. Laparoscopic management of benign solid and cystic lesions of the liver. Ann Surg. 1999;229:460-466.

Kirchner GI, et al. Outcome and quality of life in patients with polycystic liver disease after liver or combined liver-kidney transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1268-1277.

Klupp J, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation in therapy of advanced polycystic liver disease. Chirurg. 1996;67:515-521.

Konstadoulakis MM, et al. Laparoscopic fenestration for the treatment of patients with severe adult polycystic liver disease. Am J Surg. 2005;189:71-75.

Koperna T, et al. Nonparasitic cysts of the liver: results and options of surgical treatment. World J Surg. 1997;21:850-854.

Krohn PS, Hillingsø JG, Kirkegaard P. Liver transplantation in polycystic liver disease: a relevant treatment modality for adults? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:89-94.

Lang H, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with polycystic liver disease. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2832-2833.

Larssen TB, et al. Single-session alcohol sclerotherapy in symptomatic benign hepatic cysts performed with a time of exposure to alcohol of 10 min: initial results. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2627-2632.

TJ Li, et al. Treatment of polycystic liver disease with resection–fenestration and a new classification. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5066-5072.

Loehe F, et al. Long-term results after surgical treatment of nonparasitic hepatic cysts. Am J Surg. 2010;200:23-31.

Madariaga JR, et al. Hepatic resection for cystic lesions of the liver. Ann Surg. 1993;218:610-614.

Marks J, et al. Laparoscopic liver surgery: a report on 28 patients. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:331-334.

Martin AP, et al. Polycystic liver and kidney disease: post-transplant kidney function in patients receiving pre-emptive kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2008;21:263-267.

Martin IJ, et al. Tailoring the management of nonparasitic liver cysts. Ann Surg. 1998;228:167-172.

Masyuk TV, et al. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1104-1116.

Mekeel KL, et al. Living donor liver transplantation in polycystic liver disease. Liver Transplant. 2008;14:680-683.

Miyamoto M, et al. Nonparasitic solitary giant hepatic cyst causing obstructive jaundice was successfully treated with monoethanolamine oleate. Intern Med. 2006;45:621-625.

Moorthy K, Mihssin N, Houghton PW. The management of simple hepatic cysts: sclerotherapy or laparoscopic fenestration. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:409-414.

Morino M, et al. Laparoscopic management of symptomatic nonparasitic cysts of the liver: indications and results. Ann Surg. 1994;219:157-164.

Nakaoka R, et al. Percutaneous aspiration and ethanolamine oleate sclerotherapy for sustained resolution of symptomatic polycystic liver disease: an initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1540-1545.

Newman KD, et al. Treatment of highly symptomatic polycystic liver disease: preliminary experience with a combined hepatic resection–fenestration procedure. Ann Surg. 1990;212:30-37.

Park HC, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization therapy for a massive polycystic liver in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:57-61.

Perico N, et al. Sirolimus therapy to halt the progression of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1031-1040.

Pirenne J, et al. Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:238-245.

Pyronnet S, et al. Antitumor effects of somatostatin. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286:230-237.

Qian Q, et al. Sirolimus reduces polycystic liver volume in ADPKD patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:631-638.

Que F, et al. Liver resection and cyst fenestration in the treatment of severe polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:487-494.

Robinson TN, Stiegmann GV, Everson GT. Laparoscopic palliation of polycystic liver disease. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:130-132.

Saini S, et al. Percutaneous aspiration of hepatic cysts does not provide definitive therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:559-560.

Sanchez H, et al. Surgical management of nonparasitic cystic liver disease. Am J Surg. 1991;161:113-118.

Schnelldorfer T, et al. Polycystic liver disease: a critical appraisal of hepatic resection, cyst fenestration, and liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2009;250:112-118.

Shillingford JM, et al. The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5466-5471.

Shrestha R, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy selectively stimulates hepatic enlargement in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:1282-1286.

Simonetti G, et al. Percutaneous treatment of hepatic cysts by aspiration and sclerotherapy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1993;16:81-84.

Soravia C, et al. Surgery for adult polycystic liver disease. Surgery. 1995;117:272-275.

Starzl TE, et al. Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease. Arch Surg. 1990;125:575-577.

Swenson K, et al. Liver transplantation for adult polycystic liver disease. Hepatology. 1998;28:412-415.

Takei R, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter hepatic artery embolization for liver cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:744-752.

Tan YM, et al. Role of fenestration and resection for symptomatic solitary liver cysts. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:577-580.

Taner B, et al. Polycystic liver disease and liver transplantation: single-institution experience. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3769-3771.

Tikkakoski T, et al. Treatment of symptomatic congenital hepatic cysts with single-session percutaneous drainage and ethanol sclerosis: technique and outcome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7:235-239.

Turnage RH, et al. Therapeutic dilemmas in patients with symptomatic polycystic liver disease. Am Surg. 1988;54:365-372.

Ubara Y, et al. Renal contraction therapy for enlarged polycystic kidneys by transcatheter arterial embolization in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:571-579.

Uddin W, et al. Hepatic venous outflow obstruction in patients with polycystic liver disease: pathogenesis and treatment. Gut. 1995;36:142-145.

Ueno T, et al. Liver and kidney transplantation for polycystic liver and kidney-renal function and outcome. Transplantation. 2006;82:501-507.

van Erpecum KJ, et al. Highly symptomatic adult polycystic disease of the liver: a report of fifteen cases. J Hepatol. 1987;5:109-117.

van Keimpema L, et al. Laparoscopic fenestration of liver cysts in polycystic liver disease results in a median volume reduction of 12.5%. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:477-482.

van Keimpema L, et al. Lanreotide reduces the volume of polycystic liver: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1661-1668.

Vauthey JN, Maddern GJ, Blumgart LH. Adult polycystic disease of the liver. Br J Surg. 1991;78:524-527.

Vons C, et al. Liver resection in patients with polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1998;22:50-54.

Washburn WK, et al. Liver transplantation for adult polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:17-22.

Wernet A, et al. Ethanol-induced coma after therapeutic ethanol injection of a hepatic cyst. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:328-329.

Yang CF, et al. Single-session prolonged alcohol-retention sclerotherapy for large hepatic cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:940-943.

Yang GS, et al. Combined hepatic resection with fenestration for highly symptomatic polycystic liver disease: a report on seven patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2598-2601.

Zerem E, Imamovi G, Omerovi S. Percutaneous drainage without sclerotherapy for benign ovarian cysts. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:921-925.