53 Sickle Cell Disease

Etiology and Pathogenesis

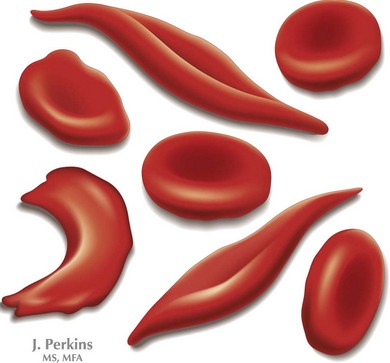

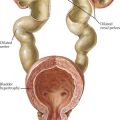

SCD is a group of inherited hemoglobinopathies associated with hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusive complications. All forms of SCD are inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion and are the result of mutations in the two β-globin genes. β-Globin is one of the major components of adult Hb and is part of a group of genes involved in oxygen transport. Two β-globin chains combine with two α-globin chains to form the predominant Hb found in human adults, HbA. In HbS, an amino acid substitution from glutamic acid to valine ultimately leads to the polymerization of HbS molecules, causing the “sickling” effect (Figure 53-1)

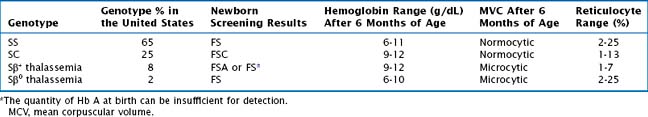

The most common form of SCD is homozygous SS. Other variants of SCD are the result of compound heterozygotes for HbS and other β-globin variants, including SC as well as Sβ+ thalassemia and Sβ0 thalassemia. All individuals who are homozygous or compound heterozygous for HbS exhibit some clinical manifestations of SCD. Symptoms usually appear by the first 6 months of life when fetal Hb dissipates, but there may be late presentations as well. There is considerable variability in clinical severity, which is related to genotype (Table 53-1). Patients with SS have the most severe clinical phenotype followed by individuals with Sβ0 thalassemia. Those with SC and Sβ+ thalassemia tend to have milder clinical phenotypes.

Diagnostic Approach

Currently in the United States, SCD testing is a standard component of newborn screening. Approximately 2000 infants with SCD are identified annually by national newborn screening programs. Patients with an abnormal newborn screen concerning for SCD should be referred to a pediatric hematologist. Confirmatory testing should be performed with Hb identification, molecular genetic testing (if available), and parental testing. Most importantly, when reviewing the results of a newborn screen, all patients with SS, Sβ0 thalassemia, and SC will have no HbA present, and patients with Sβ+ thalassemia will have some HbA, but the predominant Hb is HbS. In patients with sickle cell trait, the newborn screening will reveal FAS, in which the predominant Hbs are HbF and HbA (see Table 53-1).

Management and Therapy

Acute Complications

Vaso-occlusive Episodes

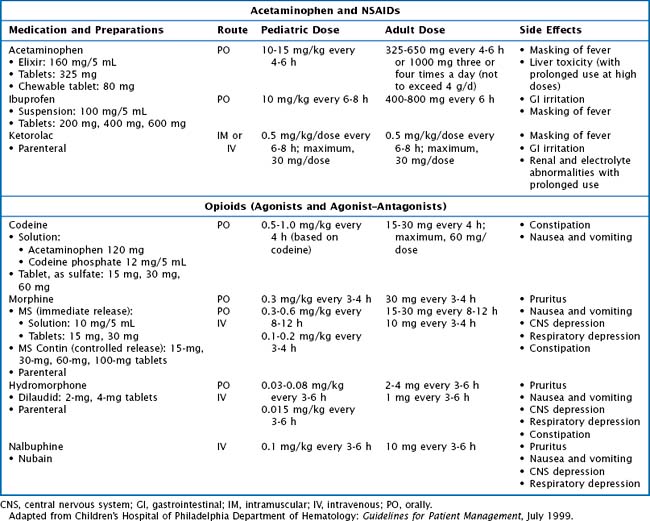

Patients with acute pain require prompt evaluation and treatment. At initial presentation, it is important to determine the cause of pain based on location and patient presentation because pain is not always related to SCD (Table 53-2). Assessment of pain should include age- and developmentally appropriate tools. Uncomplicated pain crises can be managed at home. Nonpharmacologic measures to help manage pain symptoms can be extremely helpful and include a heating pad or hot packs, massage, and play activities. Pharmacologic management of vaso-occlusive episodes (VOEs) includes a combination of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or ketorolac) and oral or IV analgesics (Tylenol, codeine, morphine, hydromorphone) (Table 53-3). It is important to adjust therapy according to the degree of pain (i.e., switching from oral to IV formulations) and to order medications to be given at scheduled intervals.

Table 53-2 Differential Diagnosis and Further Evaluation of Pain

| Location of Pain | Other Conditions to Consider | Additional Studies to Consider |

|---|---|---|

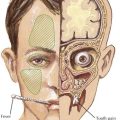

| Head or face |

CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiography; GER, gastroesophageal reflux; LP, lumbar puncture; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RAD, reactive airway disease; UA, urinalysis.

Adapted from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Department of Hematology: Guidelines for Patient Management, July 1999.

Priapism

Routine Health Maintenance

Ashley-Koch A, Yang Q, Olney RS. Sickle hemoglobin (Hb S) and sickle cell disease: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(9):839-845.

Dunlop RJ, Bennett KCLB: Pain management for sickle cell disease, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD003350, 2006.

Johnson CS. The acute chest syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2005;19:857-879.

Jones AP, et al: Hydroxyurea for sickle cell disease, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD002202, 2001.

Kwiatkowski JL, Cohen AR. Iron chelation therapy in sickle-cell disease and other transfusion-dependent anemias. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;18:1355-1377.

Lee MT, Piomelli S, Granger S, et alSTOP Study Investigators. Stroke prevention trial in sickle cell anemia (STOP): extended follow-up and results. Blood. 2006;108(3):847-852.

National Institute of Health, Division of Blood Diseases and Resources. The Management of Sickle Cell Disease. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/blood/sickle/sc_mngt.pdf

Oringanje C, Nemecek E, Oniyangi O: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for children with sickle cell disease, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD007001, 2009.

Sickle Cell Disease Association of America. Available at http://www.sicklecelldisease.org/index.phtml

Sickle Cell Kids. Available at http://www.sicklecellkids.org

Wood KC, Hsu LL, Gladwin MT. Sickle cell disease vasculopathy: a state of nitric oxide resistance. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(8):1506-1528.