CHAPTER 9 Short scar facelift

History

The short scar facelift with lateral SMASectomy was developed out of a demand from younger female patients (aged mostly in their forties) who sought facial rejuvenation but were adamantly opposed to any scarring behind the ears. These patients objected to the posterior hairline distortion, hypertrophic scars, and hypopigmentation that they often observed in their friends or mothers who had undergone facelifts. They were embarrassed to wear their hair up or in a ponytail.

Physical evaluation

Type I: The ideal candidate for short scar facelift

Type II: The good candidate for short scar facelift

Type III: The fair candidate for short scar facelift

Type IV: The poor candidate for short scar facelift

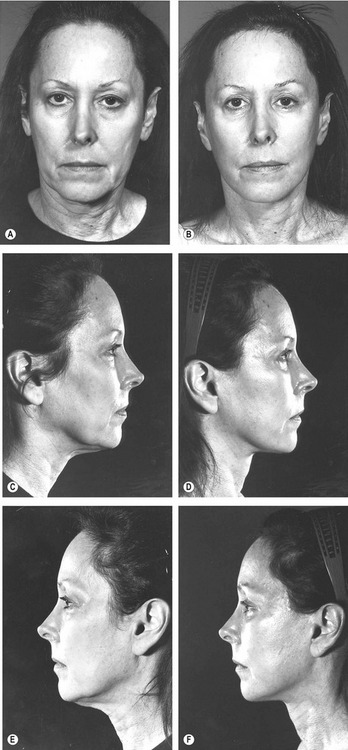

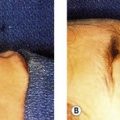

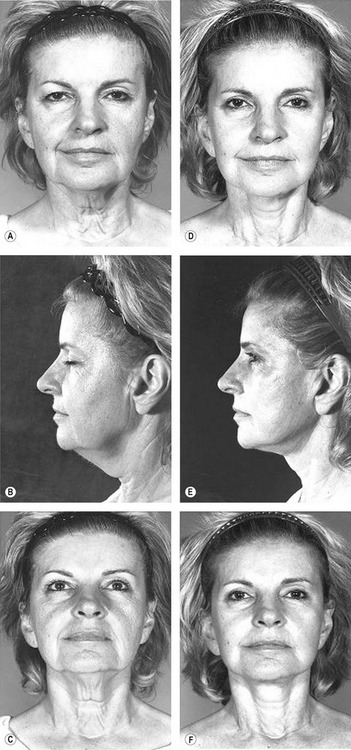

Fig. 9.8 A–F, Although this patient has a nice improvement after undergoing short-scar rhytidectomy, the 1-year postoperative result demonstrates persistent cervical laxity extending to the sternal notch. The patient was not happy and required neck revision with a classic retroauricular incision. This much cervical laxity can only be corrected with wide through-and-through undermining and removal of excess skin via the retroauricular occipital incision.

Technical steps

Incisions

When the temporal hairline shift is assessed as minimal, the preferred incision is well within the temporal hair. With this incision, it is often necessary to excise a triangle of skin below the temporal sideburn at the level of the superior root of the helix (Fig. 9.9).

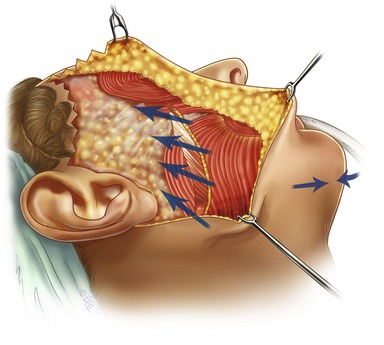

Skin flap elevation

All skin flap undermining is carried out under direct vision with scissors dissection to minimize trauma to the subdermal plexus and preserve a significant layer of subcutaneous fat on the undersurface of the flap. I prefer subcutaneous dissection in the temporal region because the skin seems to redrape better. I believe that hair loss results primarily from tension rather than superficial undermining. Subcutaneous dissection in the temporal region must be performed carefully to avoid penetrating the superficial temporal fascia that protects the frontal branch of the facial nerve. All dermal attachments between the orbicularis oculi muscle and the skin are separated up to the lateral canthus (Fig. 9.10).

Subcutaneous dissection continues over the angle of the mandible and sternocleidomastoid for 5 to 6 centimeters into the neck. This exposes the posterior half of the platysma muscle. If a submental incision has been made, the facial and lateral neck dissection is connected through-and-through to the submental dissection.

Open submental incision with medial platysma approximation

The submental incision is made either in the submental crease or just anterior to it. The subcutaneous dissection is performed with the patient’s neck hyperextended. Undermining is usually to the level of the thyroid cartilage and angle of the mandible. Suction-assisted lipoplasty is then performed with a large, single-hole cannula under direct vision. Direct fat excision is carried out, if necessary, but to avoid depressions, no subplatysma fat is removed (Fig. 9.11).

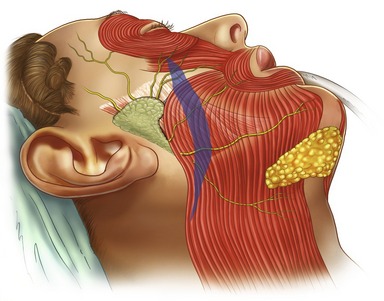

Lateral SMASectomy including platysma resection

In SMAS resection, I like to pick up the superficial fascia in the region of the tail of the parotid, extending the resection from inferolateral to supero-medial in a controlled fashion. When SMAS resection is being performed, it is important to keep the dissection superficial to the deep fascia and avoid dissection into the parotid parenchyma. Note that the size of the parotid gland varies from patient to patient; consequently, the amount of protection for the underlying facial nerve branches will also vary. Despite this, as long as the dissection is carried superficial to the deep facial fascia, ensuring that only the superficial fascia is resected, facial nerve injury as well as parotid gland injury will be prevented. In essence, this is a resection of the superficial fascia in the same plane of dissection as one would normally raise a SMAS flap.

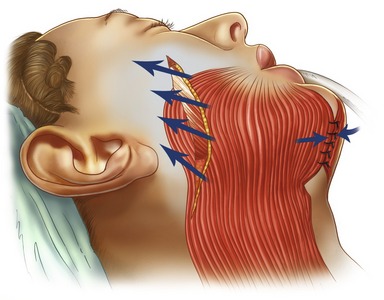

Vectors

The lines of closure of the lateral SMAS-platysma in the cheek and the lateral neck and medial platysma approximation in the submental area are depicted. Excess fat in the mastoid and submandibular areas is removed by liposuction. After SMAS resection, interrupted 3-0 PDS buried sutures are used to close the SMASectomy; the fixed lateral SMAS is evenly sutured to the more mobile anterior superficial fascia. Vectors are perpendicular to the nasolabial fold. The last suture lifts the malar fat pad, securing it to the malar fascia. It is important to obtain a secure fixation to prevent postoperative dehiscence and relapse of the facial contour (Figs 9.12 and 9.13).

Skin closure, temporal fascia and earlobe dog-ears

The first key skin suture rotates the facial flap vertically and posteriorly to lift the midface, jowls, and submandibular skin. Suture fixation is at the level of the insertion of the superior helix. I like to use a buried 3-0 PDS through the temporal fascia with a generous bite of dermis on the skin flap. Closure is under minimal to moderate tension. Staples are used to close any incisions in the hair. A wedge is usually removed at the level of the sideburn to preserve the hairline. If an anterior hairline incision has been made, I like to close it with buried 5-0 Monocryl sutures (Ethicon, Inc.) and 5-0 Nylon sutures. Extra time and attention must be spent on this closure to eliminate any dog-ears and obtain the finest scar.

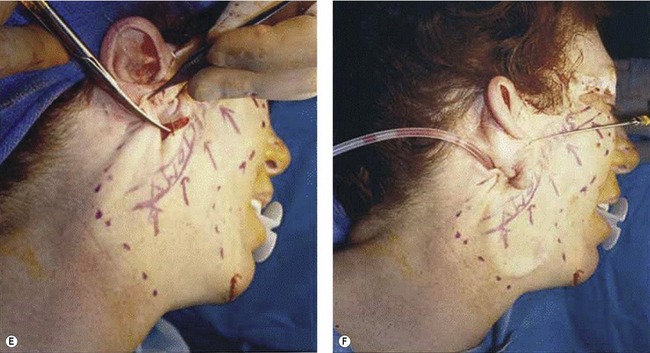

Excess skin is then trimmed from the facial flap so that there is no tension on the preauricular closure. Wound edges should be “kissing” without sutures. Trimming at the earlobe must also be without tension, and the skin flap is tucked under the lobe with 4-0 PDS sutures, taking a bite of earlobe dermis, cheek flap dermis, and conchal perichondrium to minimize tension. A small dog-ear might be present behind the earlobe; this is easily trimmed and tailored into a short incision in the retroauricular sulcus. A closed suction drain is usually brought out through a separate stab in the retroauricular sulcus (Fig. 9.14).

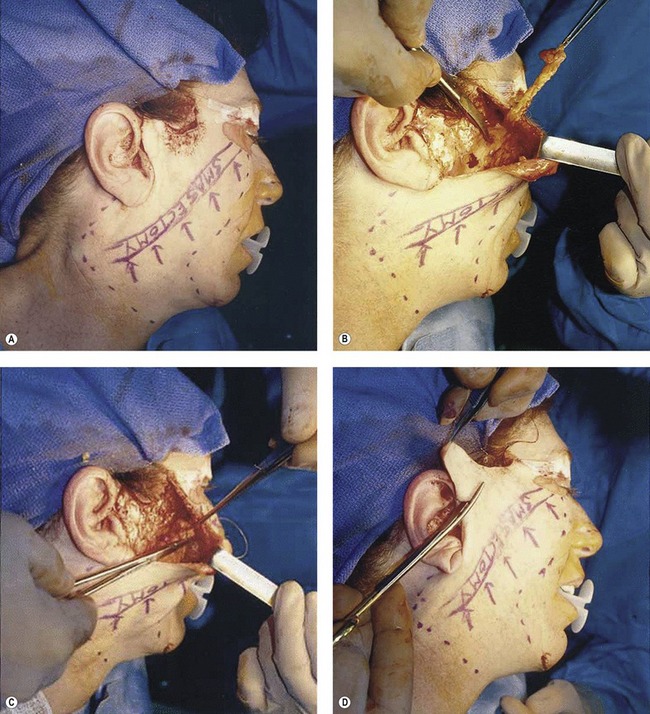

Fig. 9.14 Intraoperative and immediate postoperative views of a 64-year-old woman who underwent lateral SMASectomy via minimal incision rhytidectomy with anterior hairline incision. A, SMAS-platysma resection and temporal hairline incision are outlined. B, Area of SMAS resection; resected SMAS in forceps. C, SMAS reapproximation. D, Forceps pull in the direction of the key skin vector as excess skin is excised. E, Fitting the skin flap to the earlobe and removing the dog-ear from the retroauricular sulcus. F, Final closure with a suction drain in the neck.

Reproduced with permission from Baker, DC. Minimal incision rhytidectomy (short scar face lift) with lateral SMASectomy. Aesthet Surg J 2001;21:68–79.

Postoperative care

• Suction drains benefit cervicofacial flaps for 48 hours.

• Bulky soft head dressing for 48 hours.

• Strict postop blood pressure control for 72 hours.

• Elastic chin strap applied for 1 week in patients with complete neck undermining.

• Soft diet, no lifting, bending for 1 week, no exercise 2 weeks.

Complications of the short scar facelift

Facial paralysis (all resolved in 2 months): 0.3%.

Retroauricular pleating: 2.0%.

Pearls & pitfalls

Pitfalls (disadvantages of short scar facelift)

Summary of steps

1. The best candidates for short-scar rhytidectomy are younger, with better skin elasticity and minimal cervical laxity.

2. When the temporal hairline shift is assessed as minimal, the preferred incision is well within the temporal hair.

3. Perform lipoplasty before elevating skin flaps and avoid oversuctioning. Whenever possible, I prefer closed SAL in the neck and jowls.

4. If active prominent platysma bands are present, open the neck and undermine to perform medical platysma approximation.

5. Plication is always preferred in patients with thin faces.

6. A lateral SMASectomy is performed when debulking is aesthetically beneficial.

7. For maximal midface correction, extend plication or SMASectomy over the malar eminence just short of the lateral commissure.

8. If a lateral SMASectomy is performed, keep the dissection superficial to the deep fascia to avoid the parotid gland and facial nerves.

9. After plication or SMASectomy, the last suture lifts the malar fat pad securing it to the malar fascia.

10. Not every patient is a candidate for the short scar technique; some will benefit more from classic retroauricular and occipital incisions.

11. Finally, do not compromise the end result just to have a shorter scar.

1. Baker DC, Conley J. Avoiding facial nerve injuries in rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;64:781–795.

2. Baker DC. Complications of cervical rhytidectomy. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10:543–562.

3. Baker DC. Deep dissection rhytidectomy: A plea for caution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:1498–1499.

4. Baker DC. Lateral SMASectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:509–513.

5. Baker DC. Lateral SMASectomy. Semin Plast Surg. 2002;16:417–422.

6. Baker DC. Minimal incision rhytidectomy (short scar face lift) with lateral SMASectomy: Evolution and application. Aesthetic Surg J. 2001;21:14–26.

7. Baker DC. Minimal incision rhytidectomy (short scar face lift) with lateral SMASectomy: Operating Strategies. Aesthetic Surg J. 2001;21:68–80.

8. Baker DC, Conley J. Avoiding facial nerve injuries in rhytidectomy: Anatomical variations and pitfalls. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;64:781–795.

9. Baker DC. Hamra ST, Owsley JQ, et al. Ten year follow-up on the twin study. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, New Orleans, LA, April 2005.

10. Baker DC, Chiu ES. Reducing the incidence of hematoma requiring surgical evacuation following male rhytidectomy: A 30-year review of 985 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(7):1973–1985.