89 Sexually Transmitted Infections

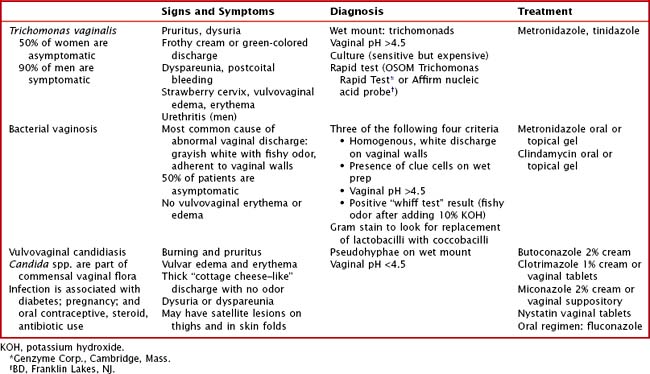

Vaginitis

Vaginitis is one of the most common symptoms among adolescent females. It typically presents as increased or malodorous vaginal discharge and vulvovaginal erythema or edema. Although this can be caused by chemical or physical irritation, infectious causes include Trichomonas vaginalis, bacterial vaginosis (caused by Gardnerella vaginalis, genital Mycoplasmas, anaerobic bacteria) and Candida spp. In postpubertal women, normal vaginal flora is dominated by lactobacilli, which decrease the pH within the vaginal canal and prevent colonization by pathogens. However, any change to the genital environment can alter this balance and result in infection. Except T. vaginalis vaginitis, infectious vaginitis is not an STI. However, vaginitis is frequently diagnosed as part of the evaluation for STIs. The signs, symptoms, diagnostic criteria, and treatments for each infection are shown in Table 89-1.

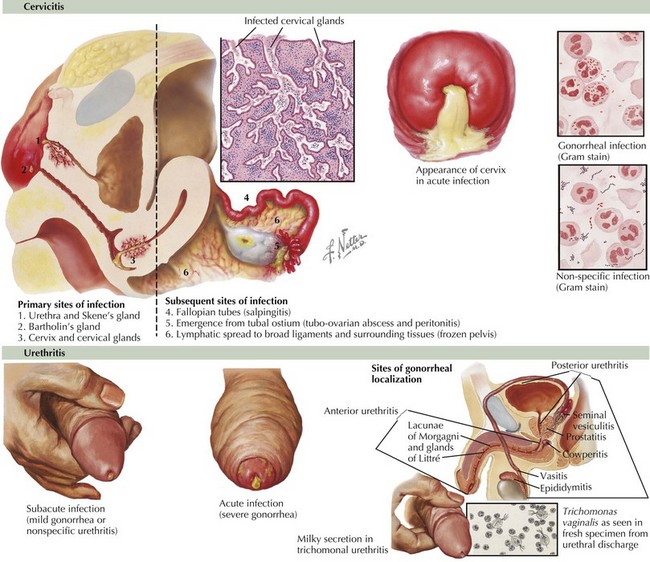

Urethritis and Cervicitis

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentations of urethritis and cervicitis and their associated infections are detailed in Table 89-2 and Figure 89-1.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

The presenting symptoms of patients with PID are described in Table 89-2. Some patients may have subclinical infection that is not diagnosed until evaluation for infertility reveals fallopian tube scarring. On examination, patients usually have lower abdominal tenderness. Pelvic examination may reveal cervical discharge; an inflamed cervix; cervical, adnexal, or uterine tenderness; or an adnexal mass. Timely diagnosis of PID is important to prevent infertility. Because the signs and symptoms of infection are not specific, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed criteria to guide diagnosis and empiric treatment (Table 89-3). Fulfillment of minimal criteria indicates presumptive treatment.

Table 89-2 Signs and Symptoms of Urethritis, Cervicitis, and Associated Syndromes in Men and Women

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; RUQ, right upper quadrant.

Table 89-3 Signs and Symptoms of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

| Minimal Criteria | Additional Criteria | Definitive Criteria |

|---|---|---|

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBC, white blood cell.

Other Manifestations of Gonococcal and Chlamydial Infection

Nongenitourinary manifestations of gonococcal and chlamydial infection include pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, and disseminated infection. Gonococcal pharyngitis should be considered for exudative pharyngitis in a sexually active adolescent. Disseminated gonococcal infection often manifests as arthritis, tenosynovitis, and dermatitis. Chlamydia is associated with Reiter’s syndrome (urethritis, spondylitis, uveitis). Both chlamydia and gonorrhea can also cause neonatal infection (see Chapter 105).

Evaluation and Management

Patients with gonorrhea or chlamydia are at risk for co-infection. Therefore, treatment guidelines recommend covering for both pathogens when treating urethritis, cervicitis, or PID (Table 89-4). This is critical in PID, in which cervical culture results are often negative. Recommendations for PID also include anaerobic coverage because of the polymicrobial nature of the infection.

Table 89-4 Treatment Recommendations for Urethritis, Cervicitis, and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease*

| Treatment | Special Considerations | |

|---|---|---|

| Nongonococcal urethritis or cervicitis |

IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; PO, oral; TOA, tubo-ovarian abscess.

* Additional alternate regimens for special populations or for those with allergies are available at www.cdc.gov/std/treatment.

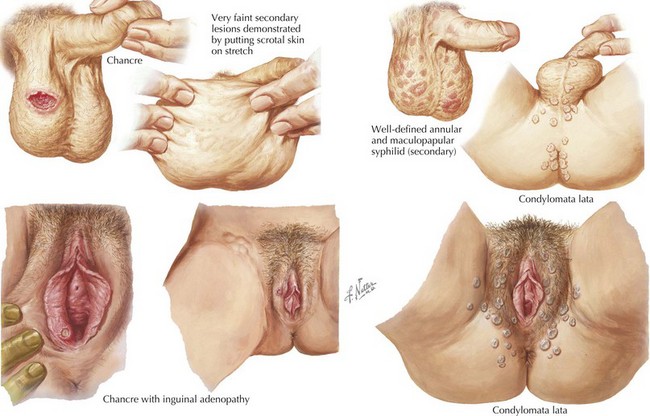

Anogenital Lesions

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment for syphilis is penicillin. Although other regimens are available to treat primary and secondary syphilis for patients who are allergic to penicillin, their efficacy has not been well demonstrated. The treatment regimens are shown in Table 89-6. Follow-up should include repeat nontreponemal quantitative antibodies (VDRL) at 6, 12, and 24 months after completion of therapy. If initially high titers have not decreased fourfold or if the titers have increased, treatment should be repeated. Further detail is available at www.cdc.gov/std/treatment.

| Primary or secondary syphilis | Benzathine penicillin G IM Other preparations of penicillin are not appropriate for treatment. |

In the setting of penicillin allergy, doxycycline or tetracycline can be used. |

| Early latent syphilis | Benzathine penicillin G | Alternate: doxycycline |

| Late latent or tertiary syphilis | Benzathine penicillin G | LP should be performed to look for neurosyphilis |

| Neurosyphilis | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G or Procaine penicillin + probenecid |

LP should be repeated every 6 months until pleocytosis has resolved |

IM, intramuscular; LP, lumbar puncture.

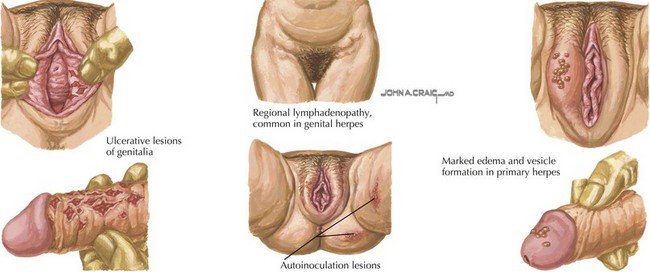

Herpes Genitalis

Clinical Presentation

Primary infection usually begins with a burning sensation in the genital area followed by the development of small (1-2 mm) vesicular lesions with an erythematous base that erode and become ulcers. The distribution of lesions can be extensive, involving the labia, vagina, perineum, cervix, and penis (Figure 89-3). The lesions are almost always painful. In primary infection, regional tender lymphadenopathy, fever, and malaise occur. Patients may also have dysuria, urinary retention, or dyspareunia. Lesions typically last from 4 to 15 days before crusting, and systemic symptoms usually peak in the first 3 to 4 days and then resolve.

Recurrent episodes are usually less severe and involve fewer lesions. Overall, the episodes last approximately 1 week compared with 3 weeks for primary infection, and the virus sheds for 2 to 7 days. There may be paresthesias or pain in the anogenital region before the appearance of ulcers but mild systemic symptoms can occur. The likelihood and frequency of recurrence varies; recurrences are more frequent in the first year after infection. Although herpes results in chronic infection, episodes are usually self-limited. Complications can occur, including secondary bacterial infection of lesions, labial adhesions, sacral radiculopathy, proctitis, encephalitis, and meningitis. Another important complication is neonatal herpes (see Chapter 105).

Diagnosis and Management

Treatment will not clear infection but may decrease the duration of symptoms and viral shedding in both primary and recurrent infection. To be effective, episodic treatment should begin within 1 day of lesion appearance. In severe infection, patients require intravenous acyclovir, 5 to 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2 to 7 days until improved followed by oral therapy to complete a 10-day course. Topical therapy has not been shown to be effective for herpes genitalis. Long-term suppressive antiviral therapy can also be given to decrease the frequency of recurrences. See Table 89-7 for treatment of HSV infections.

| Primary Infection | Suppressive Therapy | Episodic Therapy |

|---|---|---|

BID, twice a day; PO, oral; QD, every day; TID, three times a day.

Human Papillomavirus

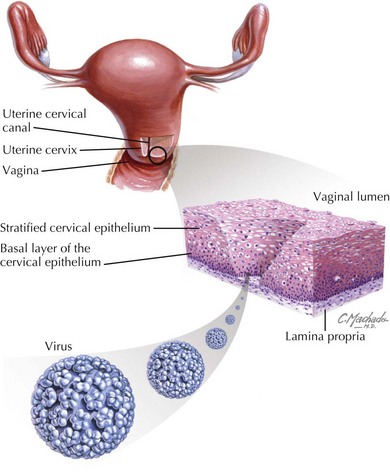

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Transmission of HPV is primarily through sexual contact; however, genital lesions can also be caused by autoinoculation from skin warts. There is also evidence that HPV types that cause skin warts are transmissible via fomites, although such evidence does not exist for genital HPV types. HPV infect rapidly dividing basal epithelial cells that predominate in the cervical transformation zone and genital areas during sexual intercourse (Figure 89-4).

Clinical Presentation

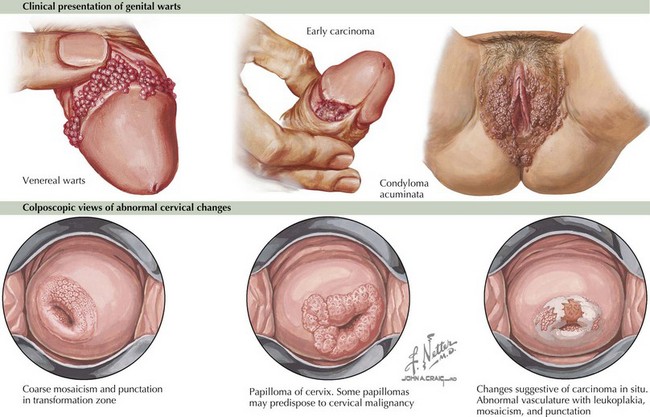

Four different types of genital warts can develop: condyloma acuminata, papular warts, keratotic warts, and flat-topped warts (Figure 89-5). The lesions are usually pinkish, red, gray, or white and are usually painless. They can, however, sometimes be associated with burning, itching, or bleeding.

Diagnosis and Management

Treatment of genital warts includes multiple patient- and clinician-directed methods (Table 89-8). Treatment of an abnormal Pap smear depends on the degree of cervical dysplasia. For the most recent updates regarding cervical cancer screening, refer to www.asccp.org.

| External genital warts For treatment of vaginal, cervical, or urethral warts, see www.cdc.gov/std/treatment |

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; BCA, bichloracetic acid; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial dysplasia; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial dysplasia; TCA, trichloroacetic acid.

Conclusion

STIs are an important part of adolescent health care. In a population that may have limited access to STI services, it is important to promote prevention and education and to provide screening during health care encounters. Although this chapter focuses on adolescents, STIs also occur in prepubertal children, and screening for sexual abuse should ensue (see Chapter 12).

American Social Health Association. Available at http://www.ashastd.org

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2006 Treatment Guidelines. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/toc.htm

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Sexually Transmitted Infections. Available at http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/sti/default.htm

Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, Rosen DS, Woods ER, editors. Adolescent Health Care: A Practical Guide. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, editors. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009.