Chapter 114 Sexually Transmitted Infections

Etiology

The risk of contracting an STI exists in any adolescent who has had oral, vaginal, or anal sexual intercourse. Physical, behavioral, and social factors contribute to the adolescent’s higher risk (Table 114-1). Adolescents who initiate sex at a younger age are at higher risk for STIs, along with youth residing in detention facilities, youth attending sexually transmitted diseases (STD) clinics, young men having sex with men (YMSM), and youth who are injecting-drug users (IDUs). Adolescence-increased STI risk may in part be attributed to risky behaviors, such as sex with multiple concurrent partners or multiple sequential partners of limited duration, failure to use barrier protection consistently and correctly, and increased biological susceptibility to infection. Although all 50 states and the District of Columbia explicitly allow minors to consent for their own sexual health services, many adolescents encounter multiple obstacles to accessing this care. Adolescents who are victims of sexual assault may not consider themselves “sexually active,” given the context of the encounter, and need reassurance, protection, and appropriate intervention when these circumstances are uncovered.

Table 114-1 CIRCUMSTANCES CONTRIBUTING TO ADOLESCENTS’ SUSCEPTIBILITY TO SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

PHYSICAL

Younger age at puberty

Cervical ectopy

Smaller introitus leading to traumatic sex

Asymptomatic nature of sexually transmitted infection

Uncircumcised penis

BEHAVIOR LIMITED BY COGNITIVE STAGE OF DEVELOPMENT

Early adolescence: have not developed ability to think abstractly

Middle adolescence: develop belief of uniqueness and invulnerability

SOCIAL FACTORS

Poverty

Limited access to “adolescent friendly” health care services

Adolescent health-seeking behaviors (forgoing care because of confidentiality concerns or denial of health problem)

Sexual abuse and violence

Homelessness

Young adolescent females with older male partners

From Shafii T, Burstein G: An overview of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents, Adolesc Med Clin 15:207, 2004.

Epidemiology

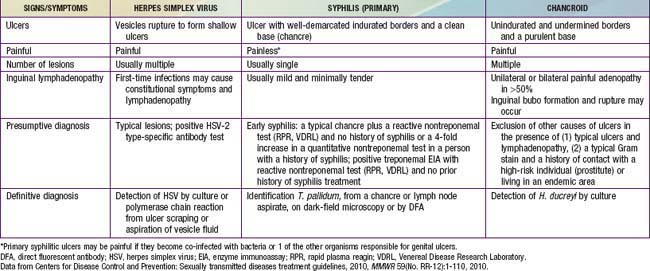

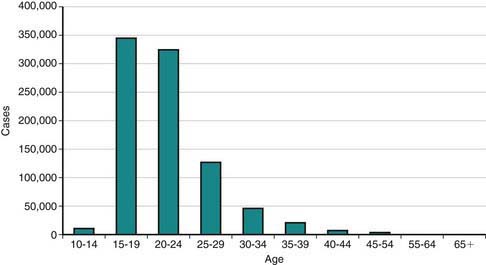

In the USA, STI prevalence varies by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Adolescents and young adults less than 25 yr of age have the highest reported prevalence of gonorrheal (Chapter 185) and chlamydial (Chapter 218) infection; among females, rates are highest in the 15-19 yr old age group, and among males, rates are highest for 20-24 yr olds. In 2008, females 15-19 yr of age had the highest reported chlamydia rate (3,275.8 per 100,000 population), followed by females 20 to 24 years of age (3,179.9 per 100,000 population) (Fig. 114-1). The reported 2008 chlamydia rate for 15-19 yr old females was almost 5 times higher than for 15-19 yr old males. Chlamydia is common among all races and ethnic groups; however, African-American, Native American/Alaska Native, and Hispanic women are disproportionately affected. In 2008, black females 15-19 yr of age had the highest chlamydia rate of any group (10,513.4), followed by black females 20-24 yr of age (9,373.9). Data from the 1999-2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimate the prevalence of chlamydia among the U.S. population was highest among African-Americans across all ages, including adolescents (Fig. 114-2).

Figure 114-1 Reported Chlamydia trachomatis cases among females by age, USA, 2008.

(Adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases in the United States, 2008 [website]. www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/trends.htm. Accessed June 22, 2010.)

(Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Chlamydia. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2008 (slide presentation). www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/slides/chlamydia.ppt. Accessed June 22, 2010.)

Reported rates of other bacterial STIs are also high among adolescents. In 2008, 15-19 yr old females had the highest (636.8 per 100,000 population) and 20-24 yr old females had the second highest gonorrhea rates (608.6 per 100,000 population) compared to any other age/sex group (Chapter 185). Gonorrhea rates among 15-24 yr old females have increased for the past 5 years. Primary and secondary (P&S) syphilis rates among 15-19 yr old females have increased annually since 2004 from 1.5 cases per 100,000 population to 3.0 per 100,000 population in 2008 (Chapter 210). Rates in women have been the highest each year in the 20-24 yr age group (5.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2008). P&S syphilis rates among 15-19 yr old males are much lower than those in older males. However, these rates have increased since 2002 from 1.3 cases per 100,000 population to 5.3 in 2008. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) rates are highest in females aged 15-24 yr when compared to older women.

Adolescents also suffer from a large burden of viral STIs. Young people in the USA are at persistent risk for HIV infection (Chapter 268). This risk is especially notable for youth of minority races and ethnicities. In 2004 in the 35 areas with long-term, confidential name-based HIV reporting, an estimated 4,883 young people aged 13-24 yr received a diagnosis of HIV infection or AIDS, representing about 13% of the persons given a diagnosis during that year. As of April 2008, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and 5 dependent areas use the same confidential name-based reporting system to collect HIV and AIDS data. Surveillance data on HIV infections provide a more complete picture of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the need for prevention and care services than does the picture provided by AIDS data alone.

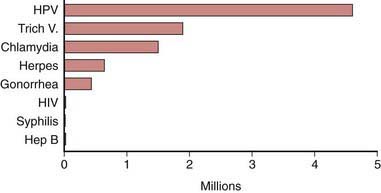

The STI with the highest estimated incidence in the USA is HPV. The 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found a third of females aged 14-24 yr were actively infected with HPV. The highest HPV infection prevalence was among females aged 20-24 yr (44.8%; 95% CI, 36.3-55.3%) (Chapter 258). Among sexually active females, half of 20-24 yr olds were HPV-infected. Although HPV infection is common, studies suggest approximately 90% of infections clear within 2 years.

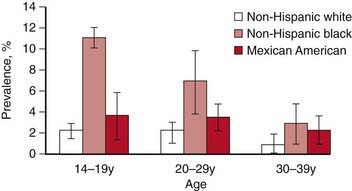

Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is the most prevalent viral STI (Chapter 244). HSV-2 prevalence rates among adolescents in the USA and young adults appear to be decreasing. The 2005-2008 NHANES estimates that 1.4% (95% CI, 1.0-2.0) of adolescents age 14-19 yr are infected with HSV-2, which is about a 76% decrease observed from the 1988-1994 NHANES and 10.5% (95% CI, 9.0-12.3) of 20-29 yr olds are HSV-2 seropositive, which is about a 39% decrease compared to the 1988-1994 NHANES (Fig. 114-3).

Figure 114-3 Estimated incidence of sexually transmitted infections among American youth ages 15 to 24 years, 2000.

(Adapted from Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W: Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000, Perspect Sex Reprod Health 36:6–10, 2004.)

Pathogenesis

During puberty, increasing levels of estrogen cause the vaginal epithelium to thicken and cornify and the cellular glycogen content to rise, the latter causing the vaginal pH to fall. These changes increase the resistance of the vaginal epithelium to penetration by certain organisms (including Neisseria gonorrhoeae) and increase the susceptibility to others (Candida albicans and Trichomonas, Chapter 276). The transformation of the vaginal cells leaves columnar cells on the ectocervix, forming a border of the 2 cell types on the ectocervix, known as the squamocolumnar junction. The appearance is referred to as ectopy (Fig. 114-4). With maturation, this tissue involutes. Prior to involution, it represents a unique vulnerability to infection for adolescent females. A 15 yr old sexually active girl with endocervical colonization has a 1:8 chance of developing PID compared to the 1:80 chance for a 24 yr old. As a result of these physiologic changes, gonococcal infection becomes primarily cervical and susceptibility to ascending infection is greatest during menses, when the pH is 6.8-7.0. The association of early sexual debut and younger gynecologic age with increased risk of sexually transmitted infections supports this explanation of the pathogenesis of infection in young adolescents.

STI Screening

Early detection and treatment are the primary STI control strategies. Some of the most common STIs in adolescents, including HPV, HSV, chlamydia, and gonorrhea, are usually asymptomatic and if undetected can be spread inadvertently by the infected host. Screening initiatives for chlamydial infections have demonstrated reductions in PID cases by up to 40%. Although federal and professional medical organizations recommend annual chlamydia screening for sexually active females 24 yr and younger, in 2007, less than half (42%) of the sexually active females enrolled in commercial and Medicaid health plans were screened. The lack of a dialogue about STIs or the provision of STI services at annual preventive service visits to adolescents who are sexually experienced are missed opportunities for screening and education. Comprehensive, confidential, reproductive health services including STI screening should be offered to all sexually experienced adolescents (Table 114-2).

Table 114-2 ROUTINE LABORATORY SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS IN SEXUALLY ACTIVE ADOLESCENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS

Chlamydia trachomatis AND Neisseria gonorrhoeae

HIV

SYPHILIS

HEPATITIS C VIRUS

NO RECOMMENDATIONS

STD, sexually transmitted diseases; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; YMSM, young men who have sex with men; HPV, human papillomavirus; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010, MMWR 59(No. RR-12):1-110, 2010.

Definitions, Etiology, and Clinical Manifestations

Urethritis

Urethritis is an STI syndrome characterized by inflammation of the urethra, usually due to an infectious etiology. Urethritis may present with urethral discharge, urethral itching, dysuria, or urinary frequency. Urgency, frequency of urination, erythema of the urethral meatus, and scrotal pain are less common clinical presentations. Many patients are completely asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. On examination, the classic finding is mucoid or purulent discharge from the urethral meatus (Fig. 114-5). If no discharge is evident on exam, providers may attempt to express discharge by applying gentle pressure to the urethra from the base distally to the meatus 3-4 times. Chlamydia trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae are the most commonly identified pathogens. Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum are considered potential pathogens in nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) when chlamydia is not confirmed. NGU caused by these pathogens may be less responsive to usual NGU therapy. Trichomonas vaginalis and HSV should also be considered in the NGU differential diagnosis. Sensitive diagnostic tests for these NGU pathogens are not available but should be considered when NGU is not responsive to treatment. Noninfectious causes of urethritis include urethral trauma or foreign body. Unlike in females, urinary tract infections are fairly rare in males who have no past genitourinary medical history. In the typical sexually active adolescent male, dysuria and urethral discharge suggest the presence of an STI unless proven otherwise. Laboratory evaluation is essential to identify the involved pathogens to determine treatment, partner notification, and disease control.

Epididymitis

The inflammation of the epididymis in adolescent males is most often associated with an STI, most frequently C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae. The presentation of unilateral scrotal swelling and tenderness, often accompanied by a hydrocele and palpable swelling of the epididymis, associated with the history of urethral discharge, constitute the presumptive diagnosis of epididymitis. Testicular torsion, a surgical emergency usually presenting with sudden onset of severe testicular pain, should be considered in the differential diagnosis (Chapter 539). Males who practice insertive anal intercourse are also vulnerable to Escherichia coli infection.

Vaginitis

Vaginitis is a superficial infection of the vaginal mucosa frequently presenting as a vaginal discharge, with or without vulvar involvement (Chapter 543). Bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), and trichomoniasis are the predominant infections associated with vaginal discharge. Bacterial vaginosis is replacement of the normal H2O2–producing Lactobacillus sp. vaginal flora by an overgrowth of anaerobic microorganisms as well as Gardnerella vaginalis, Ureaplasma, and Mycoplasma. Although bacterial vaginosis is not categorized as a STI, sexual activity is associated with increased frequency of vaginosis. VVC, usually caused by C. albicans, can trigger vulvar pruritus, pain, swelling, and redness and dysuria. Findings on vaginal exam include vulvar edema, fissures, excoriations, or thick curdy vaginal discharge. Trichomoniasis is caused by the protozoan T. vaginalis. Infected females may present with symptoms characterized by a diffuse, malodorous, yellow-green vaginal discharge with vulvar irritation or may be diagnosed by screening an asymptomatic patient. Cervicitis can sometimes cause a vaginal discharge. Laboratory confirmation is recommended because clinical presentations may vary and patients may be infected with more than 1 pathogen.

Cervicitis

The inflammatory process in cervicitis involves the deeper structures in the mucous membrane of the cervix uteri. Vaginal discharge can be a manifestation of cervicitis, if the cervical discharge is profuse. Less subtle clinical manifestations of cervicitis are irregular or postcoital bleeding, mucopurulent discharge from the os, and a friable cervix. The cervical changes associated with cervicitis must be distinguished from cervical ectopy in the younger adolescent to avoid the over diagnosis of inflammation (Fig. 114-6; see Fig. 114-4). The pathogens identified most commonly with cervicitis are C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae, although no pathogen is identified in the majority of cases. HSV is a less common pathogen associated with ulcerative and necrotic lesions on the cervix.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

PID encompasses a spectrum of inflammatory disorders of the female upper genital tract, including endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, and pelvic peritonitis, usually in combination rather than as separate entities. N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis predominate as the involved pathogenic organisms in younger adolescents, although PID should be approached as multiorganism etiology, including pathogens such as anaerobes, G. vaginalis, Haemophilus influenzae, enteric gram-negative rods, and Streptococcus agalactiae. In addition, cytomegalovirus (CMV) (Chapter 247), Mycoplasma hominis, U. urealyticum, and Mycoplasma genitalium (Chapter 216), may be associated with PID.

Genital Ulcer Syndromes

Clinical characteristics differentiating the lesions of the most common infections associated with genital ulcers are presented in Table 114-3, along with the required laboratory diagnosis to identify the causative agent accurately. The differential diagnosis includes Behçet disease (Chapter 155), Crohn disease (Chapter 328), and acute genital ulcers (AGU) due to Epstein-Barr virus (Chapter 246). AGU often follows a flu or mononucleosis-like illness in an immunocompetent female and is unrelated to sexual activity. The lesions are 0.5-2.5 cm in size, bilateral, symmetric, multiple, painful and necrotic, and are associated with inguinal lymphadenopathy. This primary infection is also associated with fever and malaise. The diagnosis may require EBV titers, or PCR testing. Treatment is supportive care including pain management.

Genital Lesions and Ectoparasites

Lesions that present as outgrowths on the surface of the epithelium and other limited epidermal lesions are included under this categorization of syndromes. HPV can cause genital warts and genital cervical abnormalities that can lead to cancer. Genital HPV types are classified according to their association with cervical cancer. Infections with low-risk types, such as HPV types 6 and 11, can cause benign or low-grade changes in cells of the cervix, genital warts, and recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. High-risk HPV types can cause cervical, anal, vulvar, vaginal, and head and neck cancers. High-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are detected in approximately 70% of cervical cancers. Persistent infection increases the risk of cervical cancer. Molluscum contagiosum and condyloma lata associated with secondary syphilis complete the classification of genital lesion syndromes. As a result of the close physical contact during sexual contact, common ectoparasitic infestations of the pubic area occur as pediculosis pubis or the papular lesions of scabies (Chapter 660).

Hiv Disease and Hepatitis B

HIV and hepatitis B present as an asymptomatic, unexpected occurrences in most infected adolescents. Risk factors identified in the history or routine screening during prenatal care are much more likely to result in suspicion of infection, leading to the appropriate laboratory screening, than are clinical manifestations in this age group (Chapters 268 and 350).

Diagnosis

An essential component of the diagnostic evaluation of vaginal, cervical or urethral discharge is a chlamydia and gonorrhea NAAT. NAATs are the most sensitive chlamydia tests available and allow for noninvasive STI testing via urine and self-collected vaginal swabs in addition to testing endocervical and urethral specimens (Table 114-4). Gonorrhea and chlamydia NAATs perform well on rectal and oropharyngeal specimens and can be performed by most commercial laboratories.

Table 114-4 AMPLIFIED GONORRHEA AND CHLAMYDIA TESTS AND APPROVED SPECIMENS FOR TESTING*

| TEST TECHNOLOGY AND NAME (MANUFACTURER) | SPECIMENS APPROVED FOR TESTING |

|---|---|

| POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION | |

| COBAS AMPLICOR (CT/NG) Test (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) | |

Male: urethral, urine

* Specimens approved for testing as of June 22, 2010.

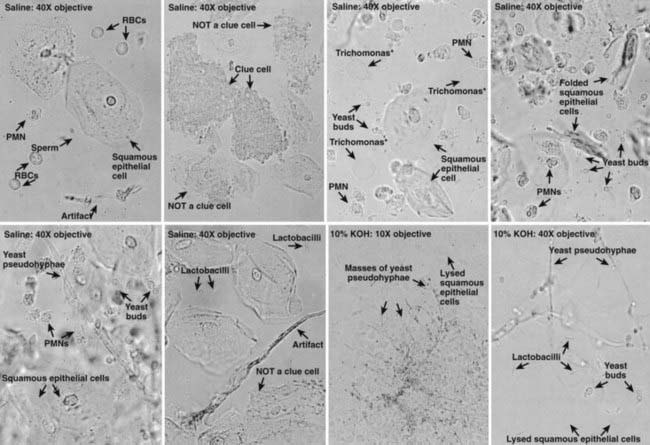

Evaluation of adolescent females with vaginitis includes laboratory data. The cause of vaginal symptoms usually can be determined by pH and microscopic examination of the discharge. Using pH paper, an elevated pH (i.e., >4.5) is common with BV or trichomoniasis. For microscopic exam, a slide can be made with the discharge diluted in 1-2 drops of 0.9% normal saline solution and another slide with discharge diluted in 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution. Examining the saline specimen slide under a microscope may reveal motile or dead T. vaginalis or clue cells (epithelial cells with borders obscured by small bacteria), which are characteristic of bacterial vaginosis. WBCs without evidence of trichomonads or yeast are usually suggestive of cervicitis. The yeast or pseudohyphae of Candida species are more easily identified in the KOH specimen (Fig. 114-7). The sensitivity of microscopy is approximately 60-70% and requires immediate evaluation of the slide for optimal results. Therefore, lack of findings does not eliminate the possibility of infection. T. vaginalis culture is more sensitive than microscopy. Objective signs of vulvar inflammation in the absence of vaginal pathogens, along with a minimal amount of discharge, suggest the possibility of mechanical, chemical, allergic, or other noninfectious irritation of the vulva (Table 114-5).

Table 114-5 PATHOLOGIC VAGINAL DISCHARGE

| INFECTIVE DISCHARGE | OTHER REASONS FOR DISCHARGE |

|---|---|

| COMMON CAUSES | COMMON CAUSES |

| Organisms | |

| Conditions | |

| LESS COMMON CAUSES | |

| LESS COMMON CAUSES | |

From Mitchell H: Vaginal discharge—causes, diagnosis, and treatment, Br Med J 328:1306–1308, 2004.

The definitive diagnosis of PID is difficult based on clinical findings alone. Clinical diagnosis is imprecise and no single historical, physical, or laboratory finding is both sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of acute PID. Clinical criteria have a positive predictive value of only 65-90% compared with laparoscopy. Although health care providers should maintain a low threshold for the diagnosis of PID, additional criteria to enhance specificity of diagnosis, such as transvaginal ultrasonography, can be considered (Table 114-6).

Table 114-6 EVALUATION FOR PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE (PID)

2010 CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Minimal Criteria

Additional Criteria to Enhance Specificity of the Minimal Criteria

Most Specific Criteria to Enhance the Specificity of the Minimal Criteria

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS (PARTIAL LIST)

GI: appendicitis, constipation, diverticulitis, gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome

GYN: ovarian cyst (intact, ruptured, or torsed), endometriosis, dysmenorrhea, ectopic pregnancy, mittelschmerz, ruptured follicle, septic or threatened abortion, tubo-ovarian abscess

Urinary tract: cystitis, pyelonephritis, urethritis, nephrolithiasis

SR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GI, gastrointestinal; GYN, gynecologic; WBC, white blood cell.

* If the cervical discharge appears normal and no WBCs are observed on the wet prep of vaginal fluid, the diagnosis of PID is unlikely and alternative causes of pain should be investigated.

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010, MMWR 59(No. RR-12):1-110, 2010.

Treatment

See Part XVI for chapters on the treatment of specific microorganisms and Tables 114-7 to 114-9. Treatment regimens using over-the-counter products for candida vaginitis and pediculosis reduce financial and access barriers to rapid treatment for adolescents, but there are potential risks for inappropriate self-treatment and complications from untreated more serious infections that must be considered before using this approach. Minimizing noncompliance with treatment, finding and treating the sexual partners, addressing prevention and contraceptive issues, offering available vaccines to prevent STIs and making every effort to preserve fertility are additional physician responsibilities. Repeat testing in 3-4 mo is recommended for patients with chlamydial and gonorrheal infections. Some experts also recommend repeat testing for trichomonas infection. Once an infection is diagnosed, partner evaluation, testing, and treatment are recommended for sexual contacts within 60 days of symptoms or diagnosis or the most recent partner if sexual contact was >60 days, even if the partner is asymptomatic. Abstinence is recommended for at least 7 days after both patient and partner are treated. A test for pregnancy should be performed for all females with suspected PID, since the test outcome will affect management.

Table 114-7 MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES FOR UNCOMPLICATED BACTERIAL STIS IN ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS

| PATHOGEN | RECOMMENDED REGIMENS | ALTERNATIVE REGIMENS AND SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia trachomatis |

IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

Adapted for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2010 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010 MMWR 59(No. RR-12):1-110, 2010.

Table 114-8 MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES FOR UNCOMPLICATED MISCELLANEOUS SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS IN ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS

| PATHOGEN | RECOMMENDED REGIMENS | ALTERNATIVE REGIMENS |

|---|---|---|

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days | |

| Phthirus pubis (pubic lice) | ||

| Sarcoptes scabiei (scabies) | Lindane (1%) 1 oz of lotion or 30 g of cream in thin layer to all areas of body from neck down; wash off in 8 hr |

Adapted for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2010 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010 MMWR 59(No. RR-12):1-110, 2010.

Table 114-9 MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES FOR UNCOMPLICATED GENITAL WARTS AND GENITAL HERPES IN ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: STD Treatment Guidelines 2010, MMWR 59(No. RR-12):1-110, 2010.

Diagnosis and therapy are often necessarily carried out within the context of a confidential relationship between the physician and the patient. Therefore, the need to report certain STIs to health department authorities should be clarified at the outset. Health departments are HIPAA-exempt and will not violate confidentiality. Health department role is to assure that treatment and case finding have been accomplished and that sexual partners have been notified of their STI exposure. Expedited partner therapy (EPT), where the patient delivers the medication or a prescription for the medication to the partner for treatment without a clinical assessment, is a strategy to reduce further transmission of infection, particularly for male partners of women with gonorrhea and/or chlamydia who are otherwise unlikely to seek care for STI exposure. In randomized trials, EPT has reduced the rates of persistent or recurrent gonorrhea and chlamydia infection. Serious adverse reactions are rare with recommended chlamydia and gonorrhea treatment regimens, such as doxycycline, azithromycin, and cefixime. Transient gastrointestinal side effects are more common but rarely result in severe morbidity. Many states expressly permit EPT or may potentially allow its practice. Resources for information regarding EPT and state laws are available at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website (www.cdc.gov/std/ept/).

American Academy of Pediatrics. Statement of endorsement—expedited partner therapy for adolescents diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1264.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 99. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1419-1444.

Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae oropharyngeal infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:902-907.

Berwald N, Cheng S, Augenbraun M, et al. Self-administered vaginal swabs are a feasible alternative to physician-assisted cervical swabs for sexually transmitted infection screening in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:360-363.

Blake DR. Approaches to chlamydia screening. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:585-586.

Burstein GR, Lowry R, Klein JD, et al. Missed opportunities for sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus, and pregnancy prevention services during adolescent health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2003;111:996-1001.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010, MMWR (in press).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommended treatment regimens for gonococcal infections and associated conditions—United States, April 2007 (website). www.cdc.gov/STD/treatment/2006/updated-regimens.htm. Accessed April 23, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinic-based testing for rectal and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections by community-based organizations—five cities, United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:716-717.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chlamydia screening among sexually active young female enrollees of health plans—United States, 2000–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:362-366.

Collins L, White JA, Bradbeer C. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Br Med J. 2006;332:66-67.

Datta SD, Sternberg M, Johnson RE, et al. Gonorrhea and chlamydia in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999 to 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:89-96.

Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813-819.

Eckert LO. Acute vulvovaginitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1244-1252.

Farhi D, Wendling J, Molinari E, et al. Non-sexually related acute genital ulcers in 13 pubertal girls. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:38-45.

Garland SM, Steben M, Sings HL, et al. Natural history of genital warts: analysis of the placebo arm of 2 randomized phase III trials of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:805-814.

Golden MR, Whittington WLH, Handsfield HH. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:676-684.

Greenwald JL, Burstein GR, Pincus J, et al. A rapid review of rapid HIV antibody tests. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2006;8:125-131.

Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370:2127-2137.

James AB, Simpson TY, Chamberlain WA. Chlamydia Prevalence among college students: reproductive and public health implications. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:529-532.

Kim JJ, Goldie SJ. Cost effectiveness analysis of including boys in a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in the United States. BMJ. 2009;339:909.

Lowe NK, Neal JL, Ryan-Wenger NA. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis compared with a DNA probe laboratory standard. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:89-95.

Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR02):1-24.

Marrazzo JM, Thomas KK, Fiedler TL, et al. Relationship of specific vaginal bacteria and bacterial vaginosis treatment failure in women who have sex with women. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:20-28.

Michels KB, zur Hausen H. HPV vaccine for all. Lancet. 2009;374:268-270.

Mollen CJ, Pletcher JR, Bellah RD, et al. Prevalence of tubo-ovarian abscess in adolescents diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:621-625.

Savaris RF, Teixeria LM, Torres TG, et al. Comparing ceftriaxone plus azithromycin or doxycycline for pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:53-60.

Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidosis. Lancet. 2007;369:1961-1971.

Tsai CS, Shepherd BE, Vermund ST. Does douching increase risk for sexually transmitted infections? A prospective study in high-risk adolescents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:38.e1-38.e8.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling to prevent sexually transmitted infections: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:491-496.

Wang SA, Harvey AB, Conner SM, et al. Antimicrobial resistance for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United Stated, 1988 to 2003: the spread of fluoroquinolone resistance. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:81-88.

Wheeler CM, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, et al. The impact of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV; types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine on infection and disease due to oncogenic nonvaccine HPV types in sexually active women aged 16–26 years. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:936-944.

Workowski KA, Berman SM, Douglas EMJr. Emerging antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: urgent need to strengthen prevention strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:606-613.

Wright TCJr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346-355.

Xu F, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:964-973.