24

Sexually transmitted infections

Examination for genital infections

Taking samples for genital infections

Introduction

Genital infections in females can be caused by infections such as bacterial vaginosis and Candida albicans that are not sexually transmitted, are common and do not usually have serious sequelae, or by sexually transmitted infections (STIs). STIs including Chlamydia trachomatis, syphilis and genital herpes can cause long-term morbidity. In women, untreated infections can lead to chronic pain or infertility and may significantly increase susceptibility to sexual transmission of HIV.

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies unsafe sex as the second most important cause (after being underweight) of ill-health in the world, causing 17% of all economic losses through ill-health in the developing countries. It estimates that there are over 340 million cases of the four major curable STIs (syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis) in adults aged 15–49 throughout the world each year; 90% in developing countries. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that at the end of 2010, 34 million adults and children were living with HIV/AIDS worldwide. The incidence of new HIV infections is around 2.7 million per year, down 21% from a peak in the late 1990s. There is cause for cautious optimism: 6.6 million people (about half of those who require it) were receiving antiretroviral therapy at the end of 2010, with an estimated 2.5 million deaths and 350 000 vertical transmissions to children averted through treatment since 1995. The main burden of the epidemic is felt in sub-Saharan Africa, where three women are newly infected to every two men. Nonetheless, in 22 African countries, HIV incidence fell by more than a quarter over the decade to 2010 and African women are more likely to access antiretroviral therapy than their male counterparts.

There have been dramatic changes in the pattern of STI over the past 50 years. In the UK, there was a decline in syphilis following the end of the Second World War, and in gonorrhoea from the 1970s, until the 1990s. However, during this time, there was an increase in chlamydia, herpes, wart virus and HIV infections. From the mid-1990s, the downward trend in the bacterial STIs then reversed, and viral STIs continued to increase. Cases of chlamydia, genital herpes and genital warts have continued to rise in both men and women, but gonorrhoea rates peaked in 2002 and have then steadily declined. A dramatic rise in cases of syphilis between 2000 and 2006 was largely attributable to cases in men, particularly men-who-have-sex-with-men, although there was a 438% rise in cases in women. Syphilis diagnoses then declined slowly but remain a concern – untreated syphilis in early pregnancy leads to a stillbirth rate of 25%. The number of diagnoses of HIV in the UK peaked in 2005 and has since fallen slightly, to around 6000 cases per year. However the number acquired within the UK almost doubled between 2001 and 2010 and now exceeds the total acquired abroad. Rises in STI diagnoses in women have been greatest in those aged 15–19 years, and have continued despite advances in prevention and treatment. Contributory factors include changes in sexual behaviour, early sexual debut, increased geographical mobility within and between countries, the emergence of drug-resistant strains, symptomless carriers, lack of public education, the reluctance of some patients to seek treatment and barriers to accessing testing and treatment services affecting those most at risk of infection.

The risk of STI acquisition is increased with younger age (under 25), prior STI diagnosis, frequent partner change or concurrent partners, non-use of condoms and high rates of condom errors. A number of groups including individuals who misuse drugs or alcohol; looked after and accommodated adolescents; sex workers; prisoners; those with sexual compulsion and addiction; and those with learning disabilities or poor mental health are often regarded as having high risk of STI. Although definitive evidence for increased STI prevalence is mixed or lacking, clinicians maintain a low threshold for STI testing in these groups. For many women, particularly in developing countries, it is the social and demographic risk factors affecting the community from which she chooses a regular partner, rather than her own individual risk factors, that determine STI risk.

Principles of STI management

Most STIs are asymptomatic and only a small proportion of women who present with symptoms such as vaginal discharge have an STI. Conversely, about 70% of women with chlamydia, 50% with gonorrhoea, 65% with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), 30% with genital warts and 50% with genital herpes, have no symptoms. Hence, performing STI testing solely in all women who present with genital symptoms will result in large numbers of tests being performed on women at very low risk of STI, but miss or delay a diagnosis in women at risk both of serious complications and of onward horizontal and vertical transmission of infection. Opt-out testing for HIV and syphilis infection are routine parts of antenatal care in the UK, and the English National Chlamydia Screening Programme tested over 2 million young men and women in 2011, diagnosing almost 150 000 chlamydial infections. These population-level interventions, along with vaccination for HPV (human papillomavirus) and opportunistic testing for infections have had some impact on the prevalence of infection and the rate of serious sequelae. In routine clinical practice, the risk of adverse outcomes is reduced by maintaining a low threshold for performing tests in both symptomatic and asymptomatic women, a high level of awareness of the genital and non-genital manifestations of STI and above all, routinely including a risk assessment in clinical history-taking. For example, routine questions confirming a history of sex with partners from groups with elevated HIV prevalence, such as those of African origin, in a woman presenting for the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, might result in an early diagnosis of HIV infection, significantly extending life expectancy.

Once an STI has been diagnosed, partner notification (contact tracing) is essential in the management of HIV and bacterial STIs both to prevent reinfection in those that are curable and to avoid further onward transmission. Partner notification strategies include: patient referral, where the patient informs recent partner(s); provider referral, where details are passed to a healthcare professional who then contacts the partners; and conditional referral, where provider referral is initiated if patient referral has not occurred after an agreed period has elapsed. In provider referral it is usual to protect the identity of the index patient. Enhanced partner notification strategies include providing the patient with antibiotic treatment for the partner or with a pharmacy voucher for treatment and the use of innovative web applications or mobile apps to allow patients to inform partners, while preserving anonymity, is increasing. Patients are advised to abstain from sex until they and their partner(s) have completed treatment. A follow-up consultation (in person or by phone) may be performed after treatment to check that medication has been completed, that there has been sexual abstinence, and that the partner(s) has been treated.

The need to accurately assess risk factors and to sensitively and appropriately identify current and previous partners makes good sexual history-taking a critical factor in STI management.

Sexual history

A woman who is complaining of genital symptoms expects to be asked questions related to this, but may or may not have considered the possibility of an STI. Asymptomatic women attending for other reasons, such as termination of pregnancy, may also be unaware of STI risk. Time, sensitivity and privacy must be ensured: interviews should take place in a soundproof setting. Accurate answers to a risk assessment may not be possible with a partner or relative present. Questioning should be sensitive, inclusive and appropriate, but direct, avoiding euphemisms. As with all history-taking, choice of words, and appropriate facial expressions and body language in the questioner are important. Use open language to avoid conveying any impression of being judgemental; examples are the use of inclusive words such as ‘partner’ rather than ‘boyfriend’. Permission-giving might involve providing a selection of possible answers to a question that includes those which might be judged socially or morally unacceptable, such as non-use of condoms or anal intercourse. Carefully introducing subjects or words that the patient might find difficult, the words ‘consent’ and ‘rape’ for example, can help with disclosure.

The history-taking should start by asking about the presenting complaint. An open question followed by more open questions is usually the best approach. A small number of direct closed questions will often clarify details of vaginal discharge, dysuria, vulval lumps, ulcers or lower abdominal pain. Supplementary questions about these symptoms are given below. The patient should then be asked about her gynaecological history. The final part should be the sexual history, in order to assess the risk of STIs. ‘When did you last have sex?’ is often entirely acceptable, but asking ‘Do you have a (sexual) partner?’ can be a gentler introduction if the woman is not expecting questions about sexual contacts. This can lead to questions about the woman’s most recent sexual exposure:

![]() How long ago was it?

How long ago was it?

![]() Was this with a regular partner, a one-off encounter or something else?

Was this with a regular partner, a one-off encounter or something else?

![]() If a regular partner, for how long?

If a regular partner, for how long?

![]() Was it a man or a woman?

Was it a man or a woman?

![]() What kind of contraception/protection was used?

What kind of contraception/protection was used?

![]() If condoms were used, were they used consistently and properly, and have there been any recent breakages?

If condoms were used, were they used consistently and properly, and have there been any recent breakages?

![]() Has the sexual partner got any genital symptoms?

Has the sexual partner got any genital symptoms?

Other sexual partners

Asking about ‘previous’ sexual partners immediately conveys an expectation of serial monogamy, making it even harder for a woman to disclose a concurrent partner. Around 9% of sexually active women in the UK report a concurrent sexual partnership in the previous year.

![]() When did she last have sex with a different partner? If within the past few months, the same details as above need to be obtained.

When did she last have sex with a different partner? If within the past few months, the same details as above need to be obtained.

![]() How many different partners have there been over the past few months?

How many different partners have there been over the past few months?

Assessment of HIV risk

Supplementary questions about risk of exposure to HIV infection should also be asked.

![]() Have any partners been from areas where HIV is more common, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Asia?

Have any partners been from areas where HIV is more common, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Asia?

![]() Has she ever injected drugs?

Has she ever injected drugs?

![]() Are any male partners known to be bisexual or injecting drug users.

Are any male partners known to be bisexual or injecting drug users.

Examination for genital infections

Clinical symptoms are not helpful at indicating the site of infection and are of limited use in determining which infection is likely to be present. Examination should be performed in all women with symptoms. This should be in a private room and the woman should be provided with a gown to cover the areas not being examined. All women should be offered a chaperone for both the history and examination, regardless of the practitioner’s gender. It is essential that all males have a chaperone when examining a woman’s genital tract. Ensuring that the patient is in a comfortable position, and understands what the examination and any samples taken will involve, will make the procedure easier for both patient and clinician. The woman should be in the lithotomy position, and there should be a good light source behind the examiner. The following genital examination should be performed:

![]() inspect the pubic hair and surrounding skin for pubic lice and any skin rashes

inspect the pubic hair and surrounding skin for pubic lice and any skin rashes

![]() palpate the inguinal region for lymphadenopathy

palpate the inguinal region for lymphadenopathy

![]() inspect the labia majora and minora, clitoris, introitus, perineum and perianal area for warts, ulcers, erythema or excoriation

inspect the labia majora and minora, clitoris, introitus, perineum and perianal area for warts, ulcers, erythema or excoriation

![]() inspect the urethral meatus and Skene’s (see History box) and Bartholin’s glands for any discharge or swelling

inspect the urethral meatus and Skene’s (see History box) and Bartholin’s glands for any discharge or swelling

![]() insert a bivalve speculum into the vagina

insert a bivalve speculum into the vagina

![]() inspect the vaginal walls for erythema, discharge, warts, ulcers

inspect the vaginal walls for erythema, discharge, warts, ulcers

![]() inspect the cervix for discharge, erythema, contact bleeding, ulcers or raised lesions. Mucopurulent discharge from the cervix is not a reliable indicator of infection

inspect the cervix for discharge, erythema, contact bleeding, ulcers or raised lesions. Mucopurulent discharge from the cervix is not a reliable indicator of infection

![]() perform a bimanual pelvic examination to assess size and any tenderness of the uterus, cervical motion tenderness (cervical excitation) and adnexal tenderness or masses.

perform a bimanual pelvic examination to assess size and any tenderness of the uterus, cervical motion tenderness (cervical excitation) and adnexal tenderness or masses.

Taking samples for genital infections

Syndromic management, based on a combination of clinical symptoms and signs, is appropriate for women at low risk of STI who present with a first episode of uncomplicated vaginal discharge. In most other cases, samples for microbiological testing will be required. It is important that swabs are performed adequately and that the specimen is placed in the appropriate culture or transport medium. The samples required and the infections being tested for should be explained to the patient and informed consent obtained. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is increasingly available for the diagnosis of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, herpes simplex, and, less commonly, syphilis and trichomoniasis and has simplified obtaining, transporting, storing and analysing specimens for STI diagnosis. For routine testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea in asymptomatic women, or where genital examination is not possible, a self-obtained vulvovaginal swab for NAAT testing has comparable sensitivity and specificity to physician obtained samples. When samples for culture or microscopy are required, or during the examination of a symptomatic woman, the swabs required will depend on the laboratory facilities available locally, and the symptoms. Assessment may include the following:

![]() a urethral swab for culture for gonorrhoea placed in Amies, Stuart’s or similar transport medium

a urethral swab for culture for gonorrhoea placed in Amies, Stuart’s or similar transport medium

![]() observe the vaginal discharge to see if it has the homogeneous, white appearance typical of bacterial vaginosis

observe the vaginal discharge to see if it has the homogeneous, white appearance typical of bacterial vaginosis

![]() swab the lateral vaginal walls and the pool of discharge in the posterior fornix. Smear some of the discharge onto a glass slide and allow to air dry (for Gram-staining by the laboratory for clue cells, pseudohyphae and spores)

swab the lateral vaginal walls and the pool of discharge in the posterior fornix. Smear some of the discharge onto a glass slide and allow to air dry (for Gram-staining by the laboratory for clue cells, pseudohyphae and spores)

![]() test the pH of the vaginal discharge either by touching the swab used to take the vaginal specimen onto narrow-range pH paper, or the paper can be pressed against the lateral vaginal walls with sponge holders. It is important that cervical secretions are avoided for this, as cervical mucus has a pH of 7 and any contamination will give a falsely high reading

test the pH of the vaginal discharge either by touching the swab used to take the vaginal specimen onto narrow-range pH paper, or the paper can be pressed against the lateral vaginal walls with sponge holders. It is important that cervical secretions are avoided for this, as cervical mucus has a pH of 7 and any contamination will give a falsely high reading

![]() any vaginal secretions should be wiped from the cervix

any vaginal secretions should be wiped from the cervix

![]() an endocervical swab for identification of gonorrhoea (into a commercial medium for gonococcal nucleic acid amplification testing, or for culture placed in Amies, Stuart’s or similar transport medium with the urethral swab)

an endocervical swab for identification of gonorrhoea (into a commercial medium for gonococcal nucleic acid amplification testing, or for culture placed in Amies, Stuart’s or similar transport medium with the urethral swab)

![]() an endocervical sample for chlamydia nucleic acid amplification testing (in most cases a single swab is used for both chlamydia and gonorrhoea NAAT)

an endocervical sample for chlamydia nucleic acid amplification testing (in most cases a single swab is used for both chlamydia and gonorrhoea NAAT)

![]() a blood sample for syphilis serology

a blood sample for syphilis serology

![]() a blood sample for hepatitis B testing if the woman or any of her sexual partners are from areas of high hepatitis B prevalence (e.g. sub-Saharan Africa or Asia)

a blood sample for hepatitis B testing if the woman or any of her sexual partners are from areas of high hepatitis B prevalence (e.g. sub-Saharan Africa or Asia)

![]() a blood sample for hepatitis B and C testing, if the woman or any of her sexual partners have ever injected drugs

a blood sample for hepatitis B and C testing, if the woman or any of her sexual partners have ever injected drugs

![]() hepatitis B immunization if the hepatitis B test is negative and she is at continued risk

hepatitis B immunization if the hepatitis B test is negative and she is at continued risk

![]() a blood sample for HIV testing

a blood sample for HIV testing

![]() if vesicles, ulcers or fissures are seen, a sample for herpes culture should be taken from the base of the lesion and sent to the laboratory in viral transport medium.

if vesicles, ulcers or fissures are seen, a sample for herpes culture should be taken from the base of the lesion and sent to the laboratory in viral transport medium.

Symptoms associated with genital infections

None

Many infections are completely asymptomatic, so testing should be considered on the basis of risk factors.

Vaginal discharge

An increase in vaginal discharge may be due to a number of infective and non-infective conditions (Table 24.1). Even in areas of high STI prevalence, the great majority of women presenting with vaginal discharge will not have an STI. Physiological discharge can only be diagnosed after negative swabs have excluded the infective causes.

Questions that help distinguish between the causes are:

![]() Does the discharge have an offensive odour?

Does the discharge have an offensive odour?

![]() Is there any vulval itching or soreness?

Is there any vulval itching or soreness?

![]() Are there any other symptoms such as dysuria, intermenstrual or postcoital bleeding or abdominal pain?

Are there any other symptoms such as dysuria, intermenstrual or postcoital bleeding or abdominal pain?

Dysuria

Dysuria is usually due to acute bacterial cystitis, urethritis or vulvitis (Table 24.2). External dysuria, particularly in the absence of frequency or abdominal pain, indicates irritation at the urethral meatus.

Questions that help distinguish between the causes are:

![]() Is the dysuria external, i.e. is it as the urine comes into contact with the vulval mucosa?

Is the dysuria external, i.e. is it as the urine comes into contact with the vulval mucosa?

![]() Is there any urinary frequency, nocturia or haematuria?

Is there any urinary frequency, nocturia or haematuria?

![]() Is there any vaginal discharge, post-coital or intermenstrual bleeding or abdominal pain?

Is there any vaginal discharge, post-coital or intermenstrual bleeding or abdominal pain?

![]() Are there any vulval sores or itching?

Are there any vulval sores or itching?

Vulval lumps

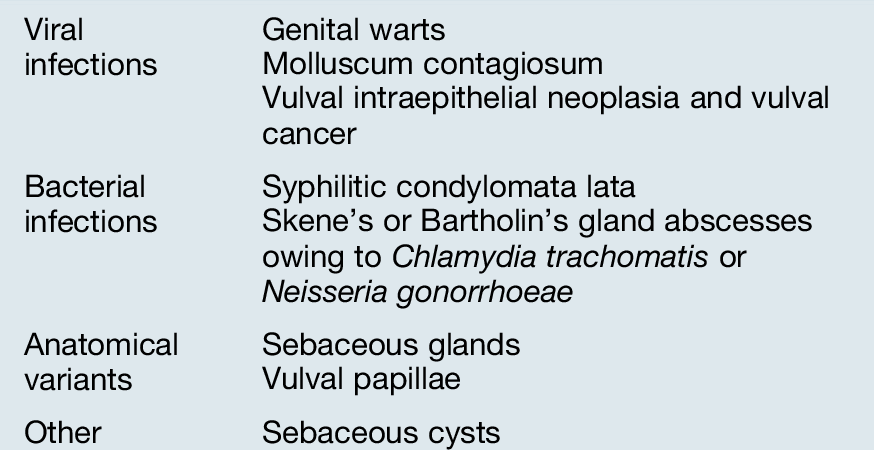

Raised lesions on the vulva can be due to infections or anatomical variants. Genital warts are by far the most common cause of vulval lumps (Table 24.3).

Questions that help distinguish between the causes are:

![]() Are the lumps painful?

Are the lumps painful?

![]() How many are there?

How many are there?

![]() How long have they been present?

How long have they been present?

![]() Are there any other symptoms such as dysuria, intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding or abdominal pain?

Are there any other symptoms such as dysuria, intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding or abdominal pain?

Vulval ulcers

Infective lesions are the most common cause of vulval ulcers, with genital herpes being the main infection in the UK (Table 24.4).

Questions that help distinguish between the causes are:

![]() Are the ulcers painful?

Are the ulcers painful?

![]() How many are there?

How many are there?

![]() How long have they been present?

How long have they been present?

![]() Are there any other symptoms such as dysuria, intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding or abdominal pain?

Are there any other symptoms such as dysuria, intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding or abdominal pain?

Lower abdominal pain

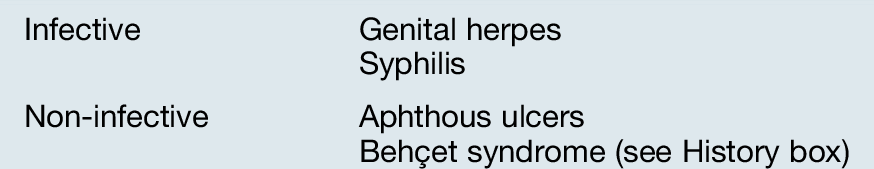

Lower abdominal pain can be caused by a number of differing conditions (Table 24.5). Infective causes are particularly common in young (under 25 years), sexually active women.

Questions that help distinguish between the causes are:

![]() Is there any vaginal discharge, post-coital or intermenstrual bleeding or deep dyspareunia?

Is there any vaginal discharge, post-coital or intermenstrual bleeding or deep dyspareunia?

![]() When was her last menstrual period (LMP); what contraception has she been using and is there any possibility of her being pregnant?

When was her last menstrual period (LMP); what contraception has she been using and is there any possibility of her being pregnant?

![]() Has she any dysuria, urinary frequency, nocturia or haematuria?

Has she any dysuria, urinary frequency, nocturia or haematuria?

![]() Has she any nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation?

Has she any nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation?

Specific infections

Bacterial vaginosis (BV)

Background information

BV is the most common cause of vaginal discharge in women of reproductive age, found in around 9% of women in general practice, 12% of pregnant women and 30% of women undergoing termination of pregnancy. BV is due to an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria, genital mycoplasmas and Gardnerella vaginalis (all of which can be present in small numbers in the vagina). Sexual partners do not need to be treated.

Symptoms and signs

![]() About 50% of women with BV are asymptomatic.

About 50% of women with BV are asymptomatic.

![]() If symptoms are present, they are mainly increased vaginal discharge and fishy odour, usually without any itch or irritation. The odour is often worse after sexual intercourse and during menstruation.

If symptoms are present, they are mainly increased vaginal discharge and fishy odour, usually without any itch or irritation. The odour is often worse after sexual intercourse and during menstruation.

![]() On examination, the discharge is milky white and adherent to the vaginal walls, and may be frothy (Fig. 24.1). There is no inflammation of the vulva or vagina.

On examination, the discharge is milky white and adherent to the vaginal walls, and may be frothy (Fig. 24.1). There is no inflammation of the vulva or vagina.

BV is due to an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria, genital mycoplasmas and Gardnerella vaginalis. The discharge is milky white, adherent to the vaginal walls, and may be frothy.

Diagnosis

A Gram-stained vaginal smear showing a depletion of normal lactobacilli and the presence of mixed organisms is the preferred method of diagnosis. BV can also be diagnosed clinically. Amsel’s criteria require that three of the following should be present: the typical thin homogeneous discharge on examination; vaginal pH > 4.5; amine odour after adding 10% potassium hydroxide to the vaginal fluid (the whiff test); clue cells on microscopy (at least 20% of all epithelial cells) of a wet-mount slide. The latter are epithelial cells covered with bacteria that are ‘clues’ to the diagnosis. Where microscopy is unavailable, a combination of typical symptoms and a raised pH may be used to make a presumptive diagnosis. Menses, semen and infection with T. vaginalis can also give a raised pH and positive amine test. Culture of vaginal secretions has no place in the diagnosis of BV. A total of 30–50% of women are colonized with G. vaginalis, anaerobes and mycoplasmas, as part of their normal vaginal flora.

Treatment and management

Asymptomatic non-pregnant women do not need treatment. Treatment is recommended in all women with symptoms and those undergoing gynaecological surgery (including termination of pregnancy), and recommended treatments are:

![]() metronidazole 400 mg orally twice daily for 5–7 days

metronidazole 400 mg orally twice daily for 5–7 days

![]() metronidazole 2 g orally single dose

metronidazole 2 g orally single dose

![]() metronidazole 0.75% vaginal gel, 5 g daily for 5 days

metronidazole 0.75% vaginal gel, 5 g daily for 5 days

![]() clindamycin 2% vaginal cream, 5 g daily for 7 days.

clindamycin 2% vaginal cream, 5 g daily for 7 days.

Complications

BV increases vaginal vault infection following hysterectomy, postpartum endometritis following caesarean section and post-abortal pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) after surgical termination of pregnancy.

It increases a woman’s risk of acquiring HIV infection two- to three-fold, and may also increase the risk of transmission of HIV to a male partner.

Candidal infections

Background information

Some 75% of all women experience at least one episode of symptomatic candida in their lifetime. About 20% of asymptomatic women have vaginal colonization with candida. Increased rates of colonization (30–40%) are found in pregnancy and uncontrolled diabetes. Recognized predisposing factors that are associated with symptomatic candida are pregnancy, diabetes, immunosuppression, antimicrobial therapy, and vulval irritation/trauma. It is not sexually acquired, so sexual partners do not need to be treated.

Symptoms and signs

![]() Vulval itching, present in nearly all symptomatic women. Thick, white vaginal discharge, vulval burning, external dysuria and superficial dyspareunia may also be present.

Vulval itching, present in nearly all symptomatic women. Thick, white vaginal discharge, vulval burning, external dysuria and superficial dyspareunia may also be present.

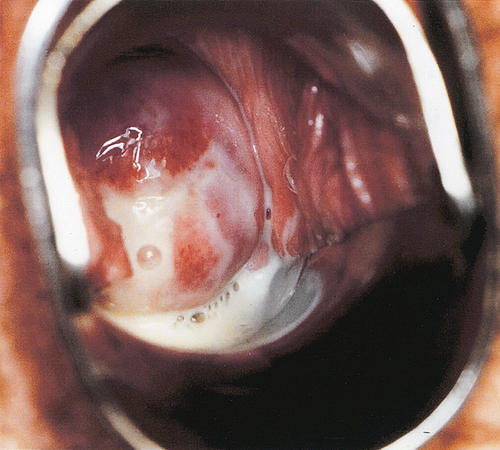

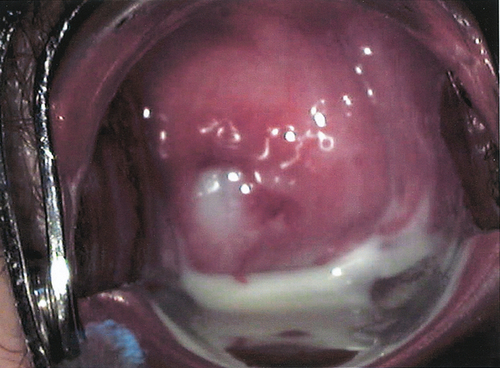

![]() On examination, vulval erythema, sometimes with satellite lesions, fissuring, excoriation and oedema may be present. There may be the typical white plaques on the vaginal walls (Fig. 24.2), but the discharge may be minimal.

On examination, vulval erythema, sometimes with satellite lesions, fissuring, excoriation and oedema may be present. There may be the typical white plaques on the vaginal walls (Fig. 24.2), but the discharge may be minimal.

(A,B) Although candida may present with these ‘typical’ white plaques, the discharge is sometimes minimal.

Diagnosis

Microscopy and culture is the most sensitive method of diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis is insensitive, but sensitivity increases with the number of symptoms and signs present. Up to half of women who self-diagnose candidal infection have another condition.

Treatment and management

There are a number of effective intravaginal and oral antifungal agents available, such as:

![]() Topical treatments:

Topical treatments:

![]() clotrimazole pessaries for 1, 3 or 6 nights

clotrimazole pessaries for 1, 3 or 6 nights

![]() econazole pessaries for 1 or 3 nights

econazole pessaries for 1 or 3 nights

![]() miconazole pessaries for 1 or 14 nights

miconazole pessaries for 1 or 14 nights

![]() Oral treatments (should not be used during pregnancy):

Oral treatments (should not be used during pregnancy):

![]() fluconazole 150 mg single dose

fluconazole 150 mg single dose

![]() itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 1 day.

itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 1 day.

Complications

There are no known long-term complications from candidal infections.

Chlamydia trachomatis

Background information

C. trachomatis is the most frequently seen bacterial STI, affecting at least 3–5% of sexually active women in the UK, and as many as 14% of those aged under 20 years. The natural history of infection is not fully understood and in more than 50% of cases the infection resolves spontaneously without complications. However, it can cause pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic pain and tubal infertility. Screening for, and treating, asymptomatic chlamydia may reduce the rate of pelvic inflammatory disease, and some countries have instituted population screening programmes.

Symptoms and signs

![]() The cervix is the primary site of infection, but the urethra is also infected in about 50%.

The cervix is the primary site of infection, but the urethra is also infected in about 50%.

![]() Approximately 70% of women with chlamydia are asymptomatic.

Approximately 70% of women with chlamydia are asymptomatic.

![]() If symptoms are present, they are usually nonspecific, such as increased vaginal discharge, dysuria and post-coital bleeding.

If symptoms are present, they are usually nonspecific, such as increased vaginal discharge, dysuria and post-coital bleeding.

![]() Lower abdominal pain, dyspareunia and intermenstrual bleeding may be present if the infection has spread beyond the cervix.

Lower abdominal pain, dyspareunia and intermenstrual bleeding may be present if the infection has spread beyond the cervix.

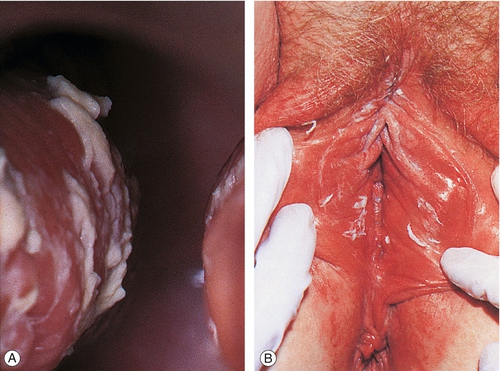

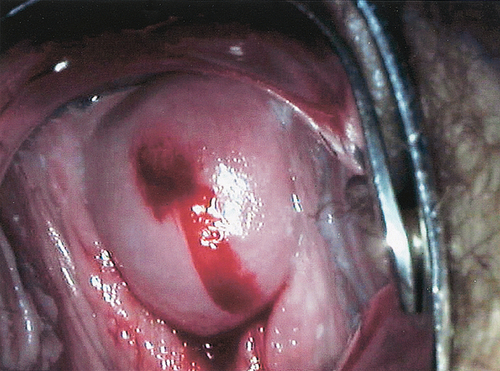

![]() On examination, there may be mucopurulent cervicitis (Fig. 24.3) and/or contact bleeding (Fig. 24.4), but the cervix may also look normal.

On examination, there may be mucopurulent cervicitis (Fig. 24.3) and/or contact bleeding (Fig. 24.4), but the cervix may also look normal.

Fig. 24.3Mucopurulent cervicitis.

This may be a feature of infection with C. trachomatis. The cervix, however, can look normal.

This can occur for a number of reasons, one of which is C. trachomatis infection.

Diagnosis

The widely used method of choice is a nucleic acid amplification test such as PCR, with a sensitivity of over 90%. Cervical or vulvovaginal swab samples are suitable for PCR testing, and first voided urine samples are also satisfactory. Self-taken vulval swabs perform as well, or better than, physician-taken cervical swabs and may be used for home-based testing. Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) tests have sensitivity of only 60–70% and are outdated.

Treatment and management

Uncomplicated chlamydial infection can be treated with:

![]() azithromycin 1 g single dose

azithromycin 1 g single dose

![]() doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 1 week

doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 1 week

Pregnant and lactating women can be treated with:

![]() erythromycin 500 mg twice daily for 14 days.

erythromycin 500 mg twice daily for 14 days.

Azithromycin is extensively used for the treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy, although this is an unlicensed indication. Patients should abstain from sex until they and their partner(s) have completed treatment. A test of cure is not necessary except after treatment in pregnancy. However, reinfection rates are 10–30%, so re-testing after 6–12 months is indicated.

Complications

C. trachomatis can spread beyond the lower genital tract, causing Skene’s and Bartholin’s gland abscesses, endometritis, salpingitis and perihepatitis. Around 3–10% of women with chlamydia develop symptomatic ascending infection (pelvic inflammatory disease; PID), which may lead to tubal damage, predisposing to tubal pregnancies and tubal infertility as well as causing chronic pain. Although asymptomatic upper genital tract infection also leads to tubal damage, the proportion of women who develop infertility following asymptomatic chlamydial infection is thought to be low (< 1%). Chlamydial infection during pregnancy can cause miscarriage, pre-term birth, postpartum infection and neonatal infection. In genetically susceptible people, a sexually acquired reactive arthritis (SARA) can occur (Reiter syndrome, see History box). Chlamydial infection increases a woman’s risk of acquiring HIV infection three- to four-fold.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Background information

Gonococcal infection rates are around 10-fold lower than those of chlamydia in the UK. There has been a steady fall in the number of infections in the UK since 2002. Rates are highest in women aged 15–19 years, in urban areas and in some black ethnic minority populations. N. gonorrhoeae is a highly adaptive organism and antibiotic resistance requires intensive and continuing surveillance.

Symptoms and signs

![]() The cervix is the primary site of infection, but the urethra is also infected in 70–90%.

The cervix is the primary site of infection, but the urethra is also infected in 70–90%.

![]() About 50% of women with gonorrhoea have no symptoms.

About 50% of women with gonorrhoea have no symptoms.

![]() The most common symptoms are increased vaginal discharge, dysuria and post-coital bleeding.

The most common symptoms are increased vaginal discharge, dysuria and post-coital bleeding.

![]() Lower abdominal pain and intermenstrual bleeding may also be present if the infection has spread beyond the cervix.

Lower abdominal pain and intermenstrual bleeding may also be present if the infection has spread beyond the cervix.

![]() On examination, there may be a purulent (Fig. 24.5) or mucopurulent cervicitis and/or contact bleeding, but again the cervix may look normal.

On examination, there may be a purulent (Fig. 24.5) or mucopurulent cervicitis and/or contact bleeding, but again the cervix may look normal.

The cervix is the primary site of infection in 90% of cases of gonococcal infection, and a purulent discharge may be seen.

Diagnosis

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) for N. gonorrhoeae are increasingly used and offer increased sensitivity but slightly lower specificity than culture. Confirmation of NAAT positive results by culture is recommended and has the advantage of allowing antibiotic sensitivity testing. If gonorrhoea is detected in a genital site (e.g. cervix or vulvovaginal swab), non-genital sites (throat, rectum) should also be tested and test of cure from these sites performed. Treatment failure, leading to the emergence of resistance is more likely in non-genital sites.

Treatment and management

Uncomplicated gonorrhoea in all women, including pregnant and lactating women, can be treated with:

![]() ceftriaxone 500 mg i.m. single dose plus azithromycin 1 g orally single dose.

ceftriaxone 500 mg i.m. single dose plus azithromycin 1 g orally single dose.

Oral cephalosporins are no longer recommended for treatment of gonorrhoea due to worldwide concerns about the emergence of resistance. About 40% of females with gonorrhoea also have C. trachomatis infection, so they should be tested and treated for chlamydia. Patients should abstain from sex until they and their partner(s) have completed treatment.

Complications

N. gonorrhoeae can spread locally beyond the lower genital tract, causing Skene’s and Bartholin’s gland abscesses, endometritis, salpingitis and perihepatitis. About 10–20% of women with acute gonococcal infection will develop salpingitis, the resulting damage predisposing to tubal pregnancies and tubal infertility. Infection in pregnancy can cause miscarriage, pre-term birth, postpartum infection and neonatal infection. Rarely, gonococcal septicaemia can occur and present as an acute arthritis/dermatitis syndrome (disseminated gonococcal infection). Gonorrhoea increases a woman’s risk of acquiring HIV infection four- to five-fold.

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Background information

PID results when infections ascend from the cervix or vagina into the upper genital tract. It includes endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess and pelvic peritonitis. The main causes are C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae, but Mycoplasma hominis and anaerobes are also frequently found. Sometimes in women with laparoscopically proven PID, no bacterial cause is found. The true incidence of PID is unknown because about two-thirds of cases are asymptomatic.

Symptoms and signs

![]() Clinical symptoms and signs vary from none to very severe.

Clinical symptoms and signs vary from none to very severe.

![]() The onset of symptoms often occurs in the first part of the menstrual cycle.

The onset of symptoms often occurs in the first part of the menstrual cycle.

![]() Women with chlamydial PID usually have clinically milder disease than women with gonococcal PID.

Women with chlamydial PID usually have clinically milder disease than women with gonococcal PID.

![]() Lower abdominal pain (usually bilateral) is the most common symptom, with increased vaginal discharge, irregular bleeding, postcoital bleeding and deep dyspareunia also present in some women.

Lower abdominal pain (usually bilateral) is the most common symptom, with increased vaginal discharge, irregular bleeding, postcoital bleeding and deep dyspareunia also present in some women.

![]() The cervix may have a mucopurulent discharge with contact bleeding, indicative of cervicitis.

The cervix may have a mucopurulent discharge with contact bleeding, indicative of cervicitis.

![]() Adnexal and cervical motion tenderness on bimanual examination is the most common sign, but pyrexia and a palpable adnexal mass may also be present.

Adnexal and cervical motion tenderness on bimanual examination is the most common sign, but pyrexia and a palpable adnexal mass may also be present.

Diagnosis

No specific symptoms, signs or laboratory tests are diagnostic of PID and the diagnosis is often made on clinical findings (presence of lower abdominal pain, increased vaginal discharge, cervical motion tenderness and adnexal tenderness on bimanual examination), which together have a specificity of 65–70% compared with laparoscopy. Nonspecific tests of inflammation such as the ESR, white cell count and C-reactive protein may be raised, and swabs taken only from the lower genital tract showing sexually transmitted pathogens, are supportive evidence. Negative results do not exclude the diagnosis. The absence of pus cells on a slide taken from the cervix or vaginal wall is a sensitive marker of the absence of PID. Differential diagnoses, including appendicitis and ectopic pregnancy should be considered and a pregnancy test should be performed. Laparoscopy, with microbiological specimens from the upper and lower genital tract, is considered the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis, but this is not always available or appropriate, particularly for those with mild symptoms. Clinical symptoms and signs do not accurately predict the extent of tubal disease found at laparoscopy.

Treatment and management

Treatment should not be delayed while waiting for bacteriological test results, as early antibiotic therapy improves outcomes. Outpatient therapy with oral antibiotics is appropriate for clinically mild to moderate disease, but hospitalization is required if there is diagnostic uncertainty, severe symptoms or signs or failure to respond to oral therapy. Intravenous therapy for the first few days is recommended in women with severe clinical disease.

Recommended regimens are:

![]() ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. daily plus doxycycline 100 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily plus metronidazole 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily for 14 days

ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. daily plus doxycycline 100 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily plus metronidazole 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily for 14 days

![]() ofloxacin 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily plus metronidazole 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily for 14 days (not suitable where there is a high risk of gonorrhoea)

ofloxacin 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily plus metronidazole 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily for 14 days (not suitable where there is a high risk of gonorrhoea)

![]() ceftriaxone 500 mg i.m. single dose, or cefoxitin 2 g i.m. single dose with probenecid 1 g orally single dose, plus doxycycline 100 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily plus metronidazole 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily for 14 days.

ceftriaxone 500 mg i.m. single dose, or cefoxitin 2 g i.m. single dose with probenecid 1 g orally single dose, plus doxycycline 100 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily plus metronidazole 400 mg (i.v. or oral) twice daily for 14 days.

Appropriate analgesia should be given. Patients should abstain from sex until they and their partner(s) have completed treatment. Women with moderate or severe clinical findings should be reviewed after 2–3 days to ensure they are improving. Lack of response to treatment requires further investigation, intravenous therapy and/or surgical intervention. All patients should be seen after treatment to check their clinical response, and that medication has been completed. Repeat testing of initially positive swabs is recommended.

Complications

The main complications from PID are due to tubal damage, with the risk of all complications increasing with severity of infection. Tubal infertility occurs in 10–12% of women after one episode of symptomatic PID, 20–30% after two episodes, and 50–60% after three or more episodes. The risk of ectopic pregnancy is increased 6- to 10-fold, with higher rates in women with several episodes. Abdominal or pelvic pain for longer than 6 months occurs in 18% of women. Women with a past history of PID are 5–10 times more likely to need hospital admission and undergo hysterectomy.

About one-third of women have repeated infections. This may be due to relapse of infection because of inadequate treatment, reinfection from an untreated partner, post-infection tubal damage or further acquisition of STIs. In 5–15% of women with salpingitis, the infection spreads from the pelvis to the liver capsule, causing perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, see History box).

Trichomonas vaginalis (TV)

Background information

Trichomonas vaginalis is uncommon in the UK – around 6000 diagnoses per year – but in other parts of the world, e.g. Africa and Asia, it remains a major cause of vaginal discharge. It is sexually transmitted and only infects the urogenital tract. Unlike bacterial vaginosis, TV causes significant inflammation.

Symptoms and signs

![]() It may be asymptomatic in 10–50% of women.

It may be asymptomatic in 10–50% of women.

![]() The most common symptom is vaginal discharge, with a malodour. There may also be vulval pruritus, external dysuria and dyspareunia.

The most common symptom is vaginal discharge, with a malodour. There may also be vulval pruritus, external dysuria and dyspareunia.

![]() On examination, there may be vulval erythema and excoriation, and the purulent discharge may be visible on the vulva. The vaginal mucosa is often inflamed, with a yellow or grey discharge.

On examination, there may be vulval erythema and excoriation, and the purulent discharge may be visible on the vulva. The vaginal mucosa is often inflamed, with a yellow or grey discharge.

Diagnosis

Microscopy of a wet-mount preparation, in which motile trichomonads can be seen, is about 70% sensitive compared with culture. Nucleic acid amplification tests, antigen detection tests and specialist culture systems are increasingly available.

Treatment and management

The recommended treatment is:

![]() metronidazole 2 g single oral dose, or

metronidazole 2 g single oral dose, or

![]() metronidazole 400 mg orally twice daily for 5–7 days.

metronidazole 400 mg orally twice daily for 5–7 days.

Of women with TV, 30% have gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia, so they should be tested for other STIs. Patients should abstain from sex until they and their partner(s) have completed treatment.

Complications

TV increases a woman’s risk of acquiring HIV infection and in pregnancy, is associated with low birth weight and pre-term delivery.

Genital warts

Background information

Genital warts are the commonest viral STI in the UK. The prevalence of infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6 and 11 in women aged 19–23 years in one UK vaccine study was 23%, and the incidence of clinical genital warts is around 0.8% per annum. HPV is highly infectious: two-thirds of sexual partners will develop warts, and HPV infection is also seen in adolescents who have had only non-penetrative sexual contact. Infection causes painless, benign, epithelial tumours caused by HPV types 6 and 11. The incubation period of months to years means that warts may appear some time into an exclusively monogamous relationship. The immunosuppression of pregnancy may cause warts to appear or recur. A vaccine against oncogenic HPV types (16 and 18) has been provided to girls aged 13, as part of a national vaccination programme in the UK since 2008. From 2012, this was be replaced by a quadrivalent vaccine, also protecting against HPV 6 and 11. In Australia, following the widespread uptake of the quadrivalent vaccine, the number of women presenting to clinics with genital warts fell by over 50% within 2 years.

Symptoms and signs

![]() Genital warts are painless, so in women they may be asymptomatic.

Genital warts are painless, so in women they may be asymptomatic.

![]() If symptomatic, it is usual that the woman has felt the vulval lumps.

If symptomatic, it is usual that the woman has felt the vulval lumps.

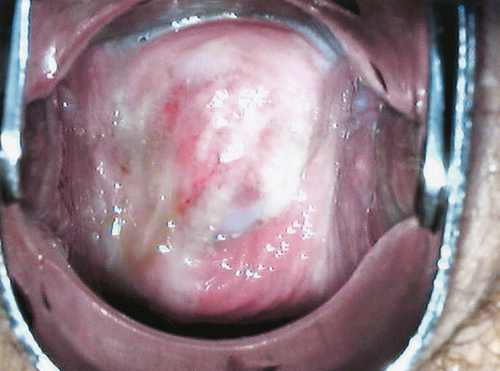

![]() On examination the flesh-coloured papules can be seen around the introital opening. They can spread onto the labia, perineum and perianal area. They may be single but are usually multiple (Fig. 24.6).

On examination the flesh-coloured papules can be seen around the introital opening. They can spread onto the labia, perineum and perianal area. They may be single but are usually multiple (Fig. 24.6).

![]() On the mucous membranes they are usually soft and cauliflower-like (condylomata acuminata).

On the mucous membranes they are usually soft and cauliflower-like (condylomata acuminata).

![]() On the drier surfaces, they are harder and keratinized.

On the drier surfaces, they are harder and keratinized.

Diagnosis

They are diagnosed by their clinical appearances. Atypical lesions should be biopsied, particularly in older women, as premalignant and malignant lesions can look similar.

Treatment and management

Warts may resolve spontaneously. No one treatment modality has been shown to be effective in all cases. Fewer (< 5) or keratinized warts can be treated with ablative therapy, such as cryotherapy, trichloroacetic acid, curettage or electrocautery. All of these can be used in pregnancy and a single treatment may be effective. Multiple, soft warts (condylomata acuminata) can be treated with podophyllotoxin solution or cream. It is a cytotoxic agent, so is contraindicated in pregnancy. Imiquimod cream works by stimulating local cell-mediated immunity, resulting in clearance of the warts. It can be used on both soft and keratinized warts, but should also not be used in pregnancy. All treatments can have recurrence rates of up to 25%, because of residual subclinical viral infection. Treatment failure should be followed by change of treatment, and management algorithms improve outcomes. Women with genital warts should be offered testing for other STIs. There is evidence that condoms reduce the spread of HPV, so patients should be advised to use condoms with new partners.

Complications

Genital warts are mainly a cosmetic problem. Psychological morbidity may arise because of their appearance, fears about cervical cancer or concerns about fidelity, if they appear in a regular relationship. Physical complications are rare; HPV 6 and 11 are not associated with cervical cancer and vertical transmission is rare.

Genital herpes

Background information

Genital herpes can be caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 or 2. Over 50% of first-episode genital herpes in the UK is due to HSV type 1. Cases have risen continuously since the 1970s, with a 60% rise between 2002 and 2011 alone. HSV-2 antibodies are found in 7.6% of blood donors, but less than 50% of donors give a clinical history of herpes, suggesting that many people have subclinical infection.

It is initially an acute vesicular/ulcerating eruption, frequently followed by recurring lesions.

HSV ascends the peripheral sensory nerves into the dorsal root ganglion, where latent infection develops. This can reactivate, giving recurrent lesions. These are not always noticeable; asymptomatic, subclinical, viral shedding occurs up to 20% of the time in HSV-2 infection. All of these reactivated episodes are potentially infectious and around 75% of first-episode infections are acquired from an asymptomatic partner.

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms range from mild irritation and soreness to severe systemic illness with extensive, confluent anogenital ulceration. Genital lesions classically pass through erythematous, vesicular and ulcerative stages before resolution.

Primary infection

![]() This is the first-ever exposure to either HSV-1 or -2. It can cause vulval soreness and external dysuria, but it can also be asymptomatic. As the symptoms are nonspecific, it may be misdiagnosed as either a urinary tract infection or candida.

This is the first-ever exposure to either HSV-1 or -2. It can cause vulval soreness and external dysuria, but it can also be asymptomatic. As the symptoms are nonspecific, it may be misdiagnosed as either a urinary tract infection or candida.

![]() On examination, there are multiple painful superficial ulcers (Fig. 24.7). Tender inguinal lymphadenopathy is also usually present.

On examination, there are multiple painful superficial ulcers (Fig. 24.7). Tender inguinal lymphadenopathy is also usually present.

Multiple painful superficial ulcers are present.

Non-primary, first-episode genital herpes

This occurs in people with previous orolabial HSV-1 who then acquire genital HSV-2 infection. There is some cross-protection from this prior infection, resulting in a milder illness than in primary infection. These non-primary infections are more likely to be asymptomatic than are primary infections.

Recurrent herpes

![]() These episodes may be asymptomatic (subclinical shedding). If symptoms are present they are usually milder than in first infections. They may be preceded by a prodrome of tingling, itching or pain in the area.

These episodes may be asymptomatic (subclinical shedding). If symptoms are present they are usually milder than in first infections. They may be preceded by a prodrome of tingling, itching or pain in the area.

![]() On examination there are usually just a few ulcers confined to a small area.

On examination there are usually just a few ulcers confined to a small area.

![]() Some 90% of people with HSV-2 infection and 60% with HSV-1 will develop recurrences within the first year. The median number of recurrences in year 1 is one in HSV-1 infection and five in HSV-2. Long-term studies show that symptomatic recurrences gradually decrease with time.

Some 90% of people with HSV-2 infection and 60% with HSV-1 will develop recurrences within the first year. The median number of recurrences in year 1 is one in HSV-1 infection and five in HSV-2. Long-term studies show that symptomatic recurrences gradually decrease with time.

Diagnosis

Nucleic acid testing (NAAT) of swabs from the lesions for HSV-1 and -2 DNA is the most sensitive method of diagnosis. Type-specific serological tests for HSV-1 and -2 are available and may be useful in assessing the susceptibility of a partner to primary infection (e.g. during pregnancy).

Treatment and management

Primary and first-episode genital herpes

Antiviral drugs reduce the severity and duration of the symptoms. They do not prevent latency, so have no effect on future recurrences.

Recommended regimens are:

![]() aciclovir 200 mg five times daily for 5 days

aciclovir 200 mg five times daily for 5 days

![]() famciclovir 250 mg three times daily for 5 days

famciclovir 250 mg three times daily for 5 days

![]() valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 5 days.

valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 5 days.

Aciclovir can be used in pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Analgesia and saline bathing are recommended. Patients can be advised to pass urine in a bath or under a shower spray of warm water, to ease external dysuria. Topical analgesia (such as lidocaine gel) may be helpful. Testing for other STIs should be performed, but this can wait until the vulval ulcers have healed, when it will be more comfortable to insert a vaginal speculum. The natural history of HSV infection should be explained, covering recurrences, subclinical viral shedding, the potential for sexual transmission, and treatments that are available.

Recurrent genital herpes

Recurrences are self-limiting and can often be managed with supportive therapy. Infrequent but severe recurrences can be treated with episodic antiviral therapy. If started early, therapy will reduce the severity and sometimes the duration of an attack, but will not reduce the number of recurrences. The patient should initiate treatment at home as soon as a recurrence is noticed.

Episodic treatment regimens are:

![]() aciclovir 200 mg five times a day for 5 days

aciclovir 200 mg five times a day for 5 days

![]() famciclovir 125 mg twice daily for 5 days

famciclovir 125 mg twice daily for 5 days

![]() valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 5 days.

valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 5 days.

For frequent recurrences (more than six recurrences in a year) suppressive therapy may be considered. In around 80% of cases, recurrences are stopped altogether. Therapy does not modify the natural history of infection, but after 12 months of treatment about 20% of patients will have fewer recurrences due to the natural decay in episode frequency. It may be restarted if frequent recurrences persist.

Suppressive treatment regimens are:

![]() aciclovir 400 mg twice daily

aciclovir 400 mg twice daily

![]() famciclovir 250 mg twice daily

famciclovir 250 mg twice daily

![]() valaciclovir 500 mg once daily.

valaciclovir 500 mg once daily.

Patients should be advised to avoid sexual contact during the prodrome and recurrence, as this is when the risk of transmission is highest. It should be explained that there is a low risk of transmission even when they have no obvious recurrence, because of subclinical viral shedding. Condoms reduce this risk and suppressive therapy has an additional effect.

Complications

Women who acquire primary genital herpes during pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester, may transmit the infection to the baby at the time of delivery. The risk of perinatal transmission with recurrent HSV is low. Genital herpes increases the acquisition and transmission of HIV two- to three-fold, although providing suppressive antiviral treatment to women with herpes who are at risk of HIV has not been successful in preventing infection. Many people with recurrent HSV infection fear rejection by sexual partners and a minority develop psychological problems. Aseptic meningitis and autonomic neuropathy can occasionally occur with primary infection, even leading to urinary retention. Rarely, the infection can disseminate, causing a life-threatening condition. This is more likely in the immunocompromised and in pregnancy.

Syphilis

Background information

Syphilis is caused by the spirochaete Treponema pallidum. Before the mid-1990s, cases of infectious syphilis in women were so rare in the UK that the value of antenatal screening for syphilis was being questioned. A resurgence of the disease from 2000 peaked in women in 2005 and has confirmed the need for continued vigilance. Between 20 and 30 cases of congenital syphilis are diagnosed annually in the UK.

Symptoms and signs

Syphilis can be asymptomatic and identified on screening serology, such as in antenatal testing.

There are several stages of symptomatic syphilis infection.

![]() Primary syphilis About 3 weeks after exposure, a chancre appears. This is usually a single, painless ulcer with rolled indurated edges, which usually goes unnoticed in women. Even without treatment, it heals spontaneously. Syphilis serology may still be negative at this stage of infection.

Primary syphilis About 3 weeks after exposure, a chancre appears. This is usually a single, painless ulcer with rolled indurated edges, which usually goes unnoticed in women. Even without treatment, it heals spontaneously. Syphilis serology may still be negative at this stage of infection.

![]() Secondary syphilis After several weeks, a generalized illness develops, with fever, malaise and skin and mucosal rashes. The rash is present on the trunk, limbs, palms and soles. Wart-like moist papules occur on the vulva (condylomata lata). Even if untreated, these symptoms and signs resolve after 3–12 weeks. Syphilis serology is strongly positive at this stage of infection.

Secondary syphilis After several weeks, a generalized illness develops, with fever, malaise and skin and mucosal rashes. The rash is present on the trunk, limbs, palms and soles. Wart-like moist papules occur on the vulva (condylomata lata). Even if untreated, these symptoms and signs resolve after 3–12 weeks. Syphilis serology is strongly positive at this stage of infection.

![]() Late syphilis Up to 40% of untreated patients will develop symptomatic late syphilis, with neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis or gummata.

Late syphilis Up to 40% of untreated patients will develop symptomatic late syphilis, with neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis or gummata.

Diagnosis

Syphilis can be diagnosed by serological testing. The initial test is likely to be an enzyme immunoassay (EIA), but, if positive, the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, and the Treponema pallidum haemagglutination (TPHA) test and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs) test should be performed.

Treatment and management

The treatment of all stages of syphilis requires long courses of antibiotics and long-term follow-up. Penicillins remain the treatment of choice. Management should be undertaken by a department of genitourinary medicine.

Complications

Without adequate treatment, complications of late syphilis can occur. Syphilis in pregnancy can cause miscarriage and stillbirth, and can be transmitted to the infant, causing congenital syphilis.

HIV infection

Background information

HIV infection can be transmitted by contact with body fluids (either sexually or through needles or blood transfusion) and by vertical transmission from mother to baby. It was estimated that 91 500 people were living with HIV in the UK in 2010, but that 24% were unaware of their infection. The rate of undiagnosed infection in women is significantly lower than men in the UK, demonstrating the effectiveness of the antenatal screening programme introduced in the 1990s. The uptake of testing among pregnant women is 96%. Antiretroviral therapy with three or more drugs has dramatically improved morbidity and mortality from HIV. There are now less than 500 deaths from AIDS each year in the UK. Late diagnosis remains a problem: 40% of these deaths occur in people diagnosed too late for effective therapy. The provision of antiretroviral treatment, male circumcision, condom use, an HIV vaccine and the use of oral or topical vaginal microbicides as pre-exposure prophylaxis have all been shown to reduce HIV transmission and have great potential when used in combination to slow the spread of the epidemic.

Symptoms and signs

![]() Most people with HIV infection have no symptoms in the first few years of infection.

Most people with HIV infection have no symptoms in the first few years of infection.

![]() There may be a mild systemic illness with fever, malaise and rash at the time of seroconversion 6–12 weeks after infection. This is rarely recognized as being HIV-related.

There may be a mild systemic illness with fever, malaise and rash at the time of seroconversion 6–12 weeks after infection. This is rarely recognized as being HIV-related.

![]() As the immune function is starting to deteriorate, infections such as oral candida and herpes zoster may occur.

As the immune function is starting to deteriorate, infections such as oral candida and herpes zoster may occur.

![]() Women with HIV infection get more frequent episodes of vaginal candida and HSV recurrences.

Women with HIV infection get more frequent episodes of vaginal candida and HSV recurrences.

![]() Opportunistic infections and HIV-related malignancies can present in many different ways.

Opportunistic infections and HIV-related malignancies can present in many different ways.

Diagnosis

Serology for evidence of antibodies to HIV is the method of diagnosis. HIV testing should be recommended as a routine part of antenatal care, STI screening or when a patient presents with any HIV clinical indicator condition. Clinical indicator conditions seen in gynaecology include cervical cancer, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (Grade 2 and above) and vulval and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Testing requires informed consent but not specialist counselling.

Treatment and management

Patients should have their CD4 count (this measures cell-mediated immune function) and HIV viral load (this measures the level of viral replication) performed about every 3 months. Antiretroviral therapy with three or more drugs should be started when the CD4 count drops to 350–400 × 109/L.

Complications

Without treatment, there is increasing damage to the cell-mediated immunity, leading to susceptibility to opportunistic infections and eventually death, a median of 9–12 years after infection. Treating the pregnant woman with triple antiretroviral therapy and avoiding breastfeeding can reduce vertical transmission. Rates of transmission are now as low as 1%. Delivery by caesarean section reduces vertical transmission in women who are not taking antiretroviral therapy, but is not thought to offer additional benefit in those on effective treatment.

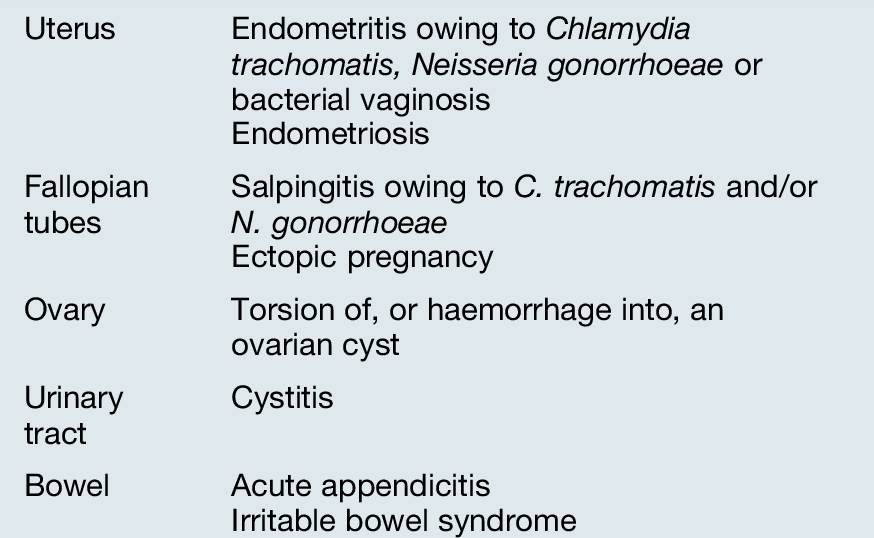

Systemic presentations of sexually transmitted infections

STIs do not always present with genital symptoms or signs. Many can cause systemic infections, which produce symptoms and signs in other systems of the body. HIV almost always presents in this way. It is not within the scope of this chapter to cover all the presentations of HIV-related opportunistic infections and malignancies, but the common early presentations are shown in Figure 24.8.