21 Sexually transmitted infections

Introduction

There are two main principles in the management of sexually transmitted infections. First, an infected patient implies that at least one other person is also infected. Thus, treating a patient in isolation will not control the spread of these diseases. Second, a patient may harbour more than one sexually transmitted infection (Box 21.1). Many infections are asymptomatic, acquired months or even years previously. Patients are often uncomfortable or embarrassed to give their sexual history or a history of genitourinary symptoms as stigma and shame are often attached to sexually transmitted infections. Remember that babies, monogamous partners and victims of rape and sexual abuse can also be infected.

Box 21.1 Sexually transmitted/microbial agents in the genital tract (diseases)

Bacteria

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhoea)

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhoea)

Chlamydia trachomatis of D-K serovars (non-gonococcal urethritis)

Chlamydia trachomatis of D-K serovars (non-gonococcal urethritis)

Chlamydia trachomatis of LGV 1-3 serovars (lymphogranuloma venereum)

Chlamydia trachomatis of LGV 1-3 serovars (lymphogranuloma venereum)

Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid)

Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid)

Mycoplasma genitalium (non-gonococcal urethritis)

Mycoplasma genitalium (non-gonococcal urethritis)

Klebsiella granulomatis (donovanosis/granuloma inguinale)

Klebsiella granulomatis (donovanosis/granuloma inguinale)

Gardnerella vaginalis, anaerobes, e.g. Mobiluncus, Bacteroides, Atopobium vaginae, Bacterial vaginosis associated bacteria 1-3, Leptotrichia, Sneathia species (bacterial vaginosis)

Gardnerella vaginalis, anaerobes, e.g. Mobiluncus, Bacteroides, Atopobium vaginae, Bacterial vaginosis associated bacteria 1-3, Leptotrichia, Sneathia species (bacterial vaginosis)

The interview and examination must be carried out in private, in strict confidence and avoiding any disapproving, judgemental or moralistic attitude. As with other clinical problems, diagnosis is achieved by history (Box 21.2), examination and relevant laboratory tests. Following diagnosis, effective treatment and partner notification/contact tracing should be instituted promptly. In children under 16 years of age, ensure they are able to comprehend (follow the Fraser’s guidelines in the UK) and it is essential to exclude any child protection issues and sexual abuse.

History

Presenting symptoms

Genital examination

Male genitalia

The penis

Note the appearance and size of the penis, the presence or absence of the prepuce and the position of the external urethral orifice. Examine the penile shaft for warts, molluscum, ulcers, burrows and excoriated papules of scabies and rashes. In Peyronie’s disease, there may be induration or a fibrotic lump inside the penile shaft. In the uncircumcised, establish that the prepuce can be readily retracted by gently withdrawing it over the glans penis. This allows inspection of the undersurface of the prepuce, the glans, the coronal sulcus and the external urethral orifice (meatus) for warts (Fig. 21.1), inflammation, ulcers and other rashes. Always carefully draw the prepuce forwards after examination; otherwise paraphimosis – painful oedema of the foreskin due to constriction by a retracted prepuce – may ensue.

The testes

Place both hands below the scrotum, the right hand being inferior, and palpate both testes. Arrange the hands and fingers as shown in Figure 21.2: this ‘fixes’ the testis so that it cannot slip away from the examining fingers. The posterior aspect of the testis is supported by the middle, ring and little fingers of each hand, leaving the index finger and thumb free to palpate. Gently palpate the anterior surface of the body of the testis; feel the lateral border with the index finger and the medial border with the pulp of each thumb. Note the size and consistency of the testis and any nodules or other irregularities. Now very gently approximate the fingers and thumb of the left hand (the effect of this is to move the testis inferiorly, which is easily and painlessly done because of its great mobility inside the tunica vaginalis). In this way, the upper pole of the testis can be readily felt between the approximated index finger and thumb of the left hand. Next move the testis upwards by reversing the movements of the hands and gently approximating the index finger and thumb of the right hand, so enabling the lower pole to be palpated. The normal testes are equal in size, varying between 3.5 and 4 cm in length.

Female genitalia

Wipe the cervix with a swab and examine it for discharge from the external cervical os, for ectopy or ectropion (ectopic columnar epithelium) and for cervicitis, warts and ulcers. Nabothian follicles may present as yellowish cysts, which may have prominent vessels on their surface, and are normal. Mucopurulent cervicitis may be caused by gonococcal or chlamydial infections (Fig. 21.3). Warts on the cervix appear as either flat or papilliferous lesions. Take tests, including a smear for cervical cytology, if indicated, to detect dysplasia and cancer of the cervix. This is particularly important because of the association of cervical cancer with oncogenic human papilloma virus infections. Then remove the speculum. Next examine the urethral orifice for discharge, inflammation and warts, and take endourethral tests (see below). Examine the anal region for lesions, as in homosexual men. If indicated, insert a lubricated proctoscope and examine the rectal mucosa for discharge or inflammation, and take tests.

HIV infections

The worldwide spread of HIV infection has resulted in a dramatic lowering of life expectancy in some countries, especially in Africa. HIV infection is categorized into A, B and C (Box 21.3), based broadly on the clinical evolution of the immunodeficiency state that leads to the development of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), on average some 8-15 years after infection if untreated.

Acute primary illness – with fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, muscle pain and sore throat, often with an erythematous, maculopapular rash and headache. Night sweats, weight loss, diarrhoea, meningism, neuropathy and oral thrush may occur. There is HIV viraemia and severe immunosuppression, indicated by a high plasma HIV-RNA and a low CD4 T-lymphocyte count.

Acute primary illness – with fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, muscle pain and sore throat, often with an erythematous, maculopapular rash and headache. Night sweats, weight loss, diarrhoea, meningism, neuropathy and oral thrush may occur. There is HIV viraemia and severe immunosuppression, indicated by a high plasma HIV-RNA and a low CD4 T-lymphocyte count.

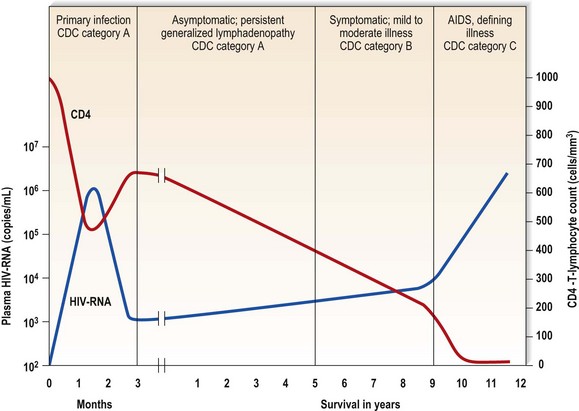

Asymptomatic phase – following the acute infection (primary HIV or acute seroconversion infection), the patient may be asymptomatic, or there may be persistent lymphadenopathy; the HIV-RNA decreases and the CD4 T-lymphocyte count increases and stabilizes (Fig. 21.4) to a baseline level.

Asymptomatic phase – following the acute infection (primary HIV or acute seroconversion infection), the patient may be asymptomatic, or there may be persistent lymphadenopathy; the HIV-RNA decreases and the CD4 T-lymphocyte count increases and stabilizes (Fig. 21.4) to a baseline level.

Symptomatic phase (category B).

Symptomatic phase (category B).

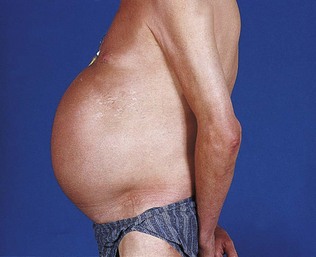

AIDS-defining illnesses (category C) – especially opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, and neoplasms such as Kaposi’s sarcoma (Fig. 21.5) and lymphoma.

AIDS-defining illnesses (category C) – especially opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, and neoplasms such as Kaposi’s sarcoma (Fig. 21.5) and lymphoma.

Box 21.3 Centre for Disease Control (CDC) HIV clinical categories

Category B: symptomatic infection excluding category A

Category C: AIDS-defining illness

Assessment of the patient with HIV infection should assess the extent of the disease and its complications. Multisystem involvement is common, and in each system there may be multiple causes. Examination of the mouth and the skin may provide clues that a patient is immunosuppressed. Common chest infections include tuberculosis, Pneumocystis and other bacterial pneumonias. Common cerebral lesions include toxoplasmosis, tuberculoma, other bacterial or fungal abscesses and lymphoma. Diarrhoea may be caused by HIV, drug treatment or opportunistic infections. Antiretroviral drug therapy may itself cause serious complications (Fig. 21.6).

Systemic examination

The skin

A generalized rash occurs in drug allergy and in acute viral infections such as HIV seroconversion illness, acute viral hepatitis, cytomegalovirus infection and infectious mononucleosis as well as acute toxoplasmosis. The generalized rash of secondary syphilis can be itchy or non-itchy, and commonly involves the palms and soles. Gummata of the skin may be present in late syphilis. In disseminated gonococcal infection, pustules with an erythematous base are seen mainly on the limbs, particularly near joints. Excoriated papules and burrows are features of scabies; generalized or crusted scabies may present as widespread crusted lesions. A psoriasis-like rash and keratoderma of the feet may be present in Reiter’s disease. Behçet’s disease causes recurrent painful orogenital ulcers. Stevens-Johnson syndrome can also present with painful orogenital ulceration and target lesions on the skin. In HIV infection, acute herpes zoster or scars of previous shingles, seborrhoeic dermatitis, severe fungal and bacterial infections, facial molluscum contagiosum and warts, bacillary angiomatosis and Kaposi’s sarcoma may be present. The last may present with purplish nodules or plaques (Fig. 21.5).

The mouth

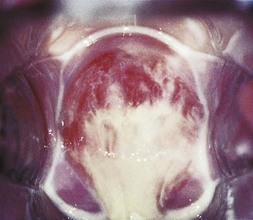

The mouth is a common site for syphilitic lesions: extragenital chancres in primary syphilis, mucous patches and snail-track ulcers in secondary syphilis, and leukoplakia, chronic superficial glossitis and gummatous perforation of the palate in late syphilis. In congenital syphilis, linear scars radiating from the mouth, known as rhagades, and Hutchinson’s incisors – dome-shaped incisor teeth with a central notch – or Moon’s/mulberry molars may be present. Genital herpes can spread to the mouth and vice versa if the patient practises orogenital intercourse. In HIV infection, oral hairy leukoplakia, consisting of persistent white hairy patches on the side of the tongue, and oral thrush, consisting of curdy white patches which can be removed, leaving behind a raw surface (Fig. 21.7) or erythematous areas, may be seen. Other oral manifestations of HIV include aphthoid ulcers, oral warts, gingivitis, severe peridontal disease, Kaposi’s sarcoma and lymphoma.

Special investigations

Gram staining

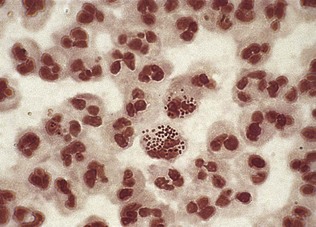

The Gram-staining procedure is outlined in Box 21.4. If the patient has passed urine just before the test, the urethral smear may show no polymorphonuclear leukocytes because the urine will have washed out the accumulated urethral material. In such cases, the patient should be asked to reattend for an overnight or late afternoon urethral smear after holding urine for 8 or more hours. Gram-negative intracellular diplococci, which appear as opposing bean-shaped cocci within polymorphonuclear leukocytes under the microscope (Fig. 21.8), suggest gonococcal urethritis. The presence of five or more polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high-power field (×1000 magnification) with a negative test for gonococci indicates non-gonococcal urethritis (Box 21.5). The term non-specific urethritis is used to describe urethritis when specific causes, including Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, trichomoniasis and non-sexually transmitted diseases such as bacterial urinary tract infection, have been excluded. However, the exclusion of C. trachomatis or M. genitalium infection requires specific and sensitive tests. A wet preparation, made by mixing urethral material using a loop with a drop of normal saline on a slide, can be examined by bright- or dark-field illumination for Trichomonas, which appear as ovoid protozoa with beating flagellae and in jerky motion. Continuing symptomatic urethritis a week or more after successful treatment for gonorrhoea indicates that the patient has postgonococcal urethritis, a non-gonococcal urethritis unmasked following treatment for gonorrhoea.

Box 21.4 Procedure for Gram staining

Fix the smear on the slide by passing it through a flame twice

Fix the smear on the slide by passing it through a flame twice

Stain with 2% crystal violet for 30 seconds, then wash with tap water

Stain with 2% crystal violet for 30 seconds, then wash with tap water

Stain with Gram’s iodine for a further 30 seconds and wash with water

Stain with Gram’s iodine for a further 30 seconds and wash with water

Decolorize with acetone for a few seconds

Decolorize with acetone for a few seconds

Wash with water and counterstain with 1% safranin for 10 seconds

Wash with water and counterstain with 1% safranin for 10 seconds

After a final wash with water, dry by pressing between filter paper

After a final wash with water, dry by pressing between filter paper

Figure 21.8 Gram-stained smear showing Gram-negative intracellular diplococci typical of Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Genital ulcer

To investigate the cause of a genital ulcer, first cleanse the base of the ulcer with normal saline, and then gently squeeze it until a drop of serum exudes. Catch the exudates on the edge of a cover slip. Place this on a glass slide and press down firmly between filter paper. Examine the slide under dark-field microscopy for the characteristic morphology and movements of Treponema pallidum (Fig. 21.9) – bending itself at an angle, rotating forward on its long axis or alternating between contraction and expansion of its coils. Dark-field examination should be repeated for several days if syphilis is suspected.

If anogenital herpes (Fig. 21.10) is suspected, the base of the blister or ulcer is swabbed and the swab sent for herpes simplex virus PCR, or placed in a viral transport medium for herpes culture. The diagnosis of donovanosis is based upon the demonstration of Donovan bodies, which stain in a bipolar fashion giving a ‘safety pin’ appearance within the cytoplasm of mononuclear cells in a Giemsa-stained tissue smear. Tissue is obtained by infiltrating the edge of the ulcer with 1% lidocaine and removing a small piece from the edge, which is then smeared onto a glass slide or crushed between two glass slides. If chancroid or lymphogranuloma venereum is suspected, culture or NAAT for Haemophilus ducreyi and Chlamydia trachomatis of the lymphogranuloma venereum serovars, respectively, may be indicated using material obtained from the ulcer or bubo.