128 Sexual Assault

• Sexual assault requires the emergency physician to competently and comprehensively evaluate and treat the physical, emotional, and legal needs of the patient.

• Management includes medical stabilization, treatment of physical injuries, emergency contraception, prophylaxis for sexually transmitted diseases, assessment of risk for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis, forensic evaluation and evidence collection, crisis intervention, arrangement for follow-up medical care, and referral to social support and legal services.

Epidemiology

Sexual assault is sexual contact of one person with another without appropriate legal consent. The precise definition varies slightly from state to state, and health care providers should familiarize themselves with the definition in their jurisdiction. It is a widespread occurrence that permeates every facet of our society and can affect anyone regardless of gender, age, race, or socioeconomic status. In 2009, 88,097 forcible rapes were reported to law enforcement in the United States.1 This number is estimated to represent only 40% of the total sexual assaults because the majority of cases go unreported.2 The National Violence Against Women Survey found that 18% of surveyed women (1 in 6) and 3% of surveyed men (1 in 33) had experienced an attempted or completed rape at some time in their lives.3 The majority of females are assaulted by acquaintances or intimate partners and 32% by a stranger. Young females between the ages of 16 and 24 are disproportionately affected.4 For affected males, underreporting of their victimization is the norm. During the last decade, an alarming increase has been observed in reports of drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA).5

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Multidisciplinary Approach

Emergency physicians (EPs) are responsible for managing both the medical and forensic needs of patients with a report of sexual assault. This is best accomplished in an organized manner, such as with a sexual assault response team (SART). Members include a sexual assault forensic examiner (SAFE), victim advocates, law enforcement officers, crime laboratory personnel, and prosecutors. A SAFE has specialized knowledge and training to perform the forensic evaluation with a standardized sexual assault evidence collection kit (SAECK). Research has shown that use of a SART/SAFE program improves the quality of forensic evidence with an increase in prosecution rates over time.6 In jurisdictions in which such teams are unavailable, ED providers are responsible for the forensic examination, and it is therefore prudent that EPs familiarize themselves with their state-specific SAECK.

Consent for Forensic Evaluation and Evidence Collection

Patients should be informed of all of the options available to them, including forensic evaluation and evidence collection, depending on timing of examination. Before proceeding with any part of this evaluation, written informed consent for all aspects of the evaluation must be obtained as listed in Box 128.1. The patient has the right to refuse all or some parts of a forensic examination, and consent can be withdrawn at any time during the examination.

History

For the ED medical record, the history of the assault should be focused on details that affect medical management of the patient in the ED, including information that will help determine the risk for injuries and what treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) should be offered. In contrast, the forensic record is driven by strict policies and procedures and should include only medical information that has a direct bearing on evaluation of the reported crime. Material that is generally considered to constitute useful background in a therapeutic context may have a prejudicial effect in a forensic context and should not be included in the forensic record. Examples include the number of previous pregnancies, past mental health treatment, and remote substance abuse. Documentation should be concise and directly relevant to the assault, including any information that is necessary to properly interpret the current physical findings. Many SAECKs contain preprinted forms that help the examiner with the history-taking process to facilitate proper documentation. Salient features of the history that should be obtained for documentation in the forensic medical record are listed in Box 128.2.7,8

Box 128.2 Pertinent Historical Features of a Sexual Assault for Forensic Documentation

Date, time, location, and physical surroundings of the assault

Date and time of hospital examination

Loss of memory or periods of unconsciousness

Patient’s narrative of events as they pertain to sexual acts or the trauma sustained

Total number of assailants and relationship to the patient

Weapons, restraints, or force used

Physical Examination

Physical examination is necessary to evaluate for signs of any trauma sustained during the sexual assault. The reported incidence of nongenital physical injuries ranges from 23% to 85%.8–15 When injuries are sustained, those most commonly seen are soft tissue injuries involving the head, face, neck, and extremities. Blunt force trauma, including penetrative blunt mechanisms, may produce contusions, which are associated with swelling, pain, tenderness, and discoloration, and lacerations from tearing of the tissues. A friction mechanism may cause abrasions. Sharp-force trauma may produce incised wounds. Bites may involve multiple mechanisms of injury. Patterned injuries suggest the specific object, weapon, or mechanism used to produce its characteristic shape.

Published rates of female genitoanal injury vary widely from 6% to 65%, with most investigators reporting a range of 10% to 30%.8–18 Risk factors for injuries included examination within 24 hours of the assault, presence of nongenital injury, threats of violence, and age younger than 20 and older than 40 years.8–18 The genital structures most frequently injured as a result of a penetrative mechanism are the fossa navicularis and posterior fourchette, followed by the labia minora and hymen. It is paramount that these areas be inspected carefully during the examination.

Forensic Evaluation: Evidence Collection and Chain of Custody

Once a patient consents to evidence collection, the steps delineated in the kit should be followed. Evidence collection should be guided by the history of the assault. Box 128.3 lists potential specimens to be gathered for forensic evidence collection.19,20

Box 128.3 Potential Specimens to Be Gathered for Forensic Evidence Collection

Evidence is lost in an exponential manner over time. As a result, evidence collection may have to be augmented based on time of evaluation after the assault. Oral and anal swabs should be collected only if the patient is initially evaluated within 24 hours of the assault because the yield thereafter is 0%. In addition, cervical sampling should be considered for evaluations between 96 and 120 hours after the assault to increase the chance of detecting spermatozoa. Seminal fluid, as evidenced by spermatozoa, high levels of acid phosphatase, or p30 prostate-specific antigen, is recovered from 38% to 48% of sexual assault patients.9

Diagnostic Testing

Tips and Tricks

Forensic Evaluation

SART/SAFE programs coordinate patient care and improve evidence collection and prosecutions.

Emergency physicians should familiarize themselves with the SAECK used in their jurisdiction.

If the patient wants something to drink before the forensic evaluation has started and she consents, collect the oral swabs first and be sure to maintain chain of custody.

If the patient wants to urinate before the forensic evaluation has started, give her a collection cup for the urine pregnancy test and toxicology screen, and inform her not to wipe the genital area afterward. Be sure to maintain chain of custody of this sample.

SAECK, Sexual assault evidence collection kit; SAFE, sexual assault forensic examiner; SART, sexual assault response team.

Mandatory Reporting

Laws regarding mandatory reporting of adult sexual assault victims vary from state to state and can be broken down into laws that specifically require providers to report treatment of a rape victim to law enforcement, laws that require reporting of injuries that may include rape, laws relating to other crimes or injuries that may have an impact on rape and sexual assault victims, and laws regarding sexual assault forensic examinations that may affect rape and sexual assault reporting.21,22 It is prudent for EPs to be well informed of the local reporting regulations in their jurisdictions.

Treatment

Hospital Management

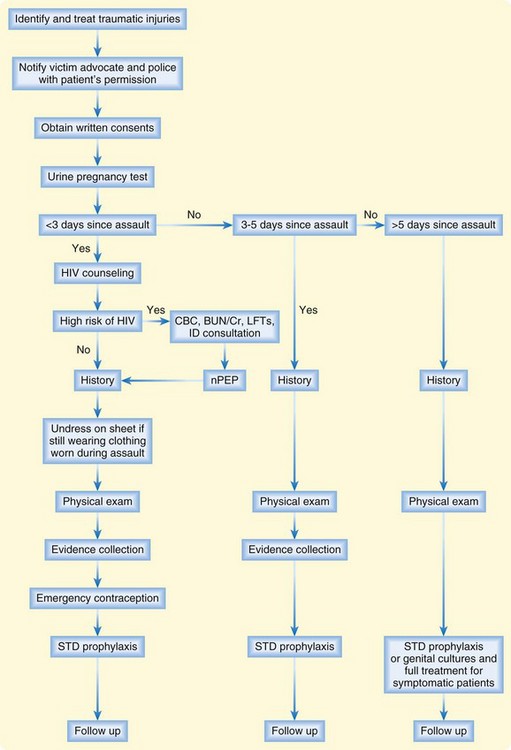

A patient with a report of sexual assault may go to the ED immediately after or long after the assault. The time since the assault determines how these patients are managed, including what interventions and treatments are recommended. Figure 128.1 outlines the scope of evaluation and treatment of sexual assault based on the timing of initial evaluation.

Medical Stabilization and Management of Physical Injuries

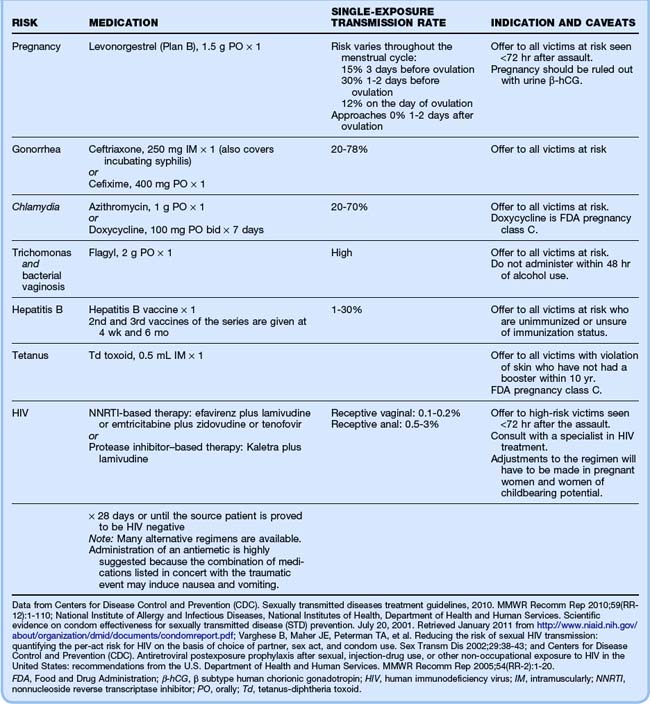

Injuries related to the assault, such as soft tissue injuries and fractures, should be treated appropriately. The advanced trauma life support protocol should be followed when assessing a trauma patient. Nearly 20% of sexual assault victims require medical procedures or interventions.10,23 Tetanus prophylaxis should be considered in patients with violation of skin integrity who have not had a booster within 10 years. After treatment of the physical injuries, the focus should transition to emergency contraception, STD prophylaxis, and risk assessment for nPEP. Table 128.1 lists the recommended prophylaxis regimen for sexual assault patients. Forensic evaluation and evidence collection follow suit.24–27

Emergency Contraception

Overall, the risk for pregnancy following sexual assault is 5%.28 The risk varies throughout the menstrual cycle, as shown in Table 128.1. Regardless of where she is in her cycle, following a negative pregnancy test, all females of childbearing age with a report of sexual assault should be offered emergency contraception (see Chapter 129 for further details).29–31

Sexually Transmitted Disease Prophylaxis

The risk of acquiring an STD following a sexual assault is significant, with reported rates of 4% to 56%, depending on the circumstances of the assault.32 Given the difficulty in accurately assessing risk, as well as poor compliance with follow-up visits in this patient population, which has been estimated to be 10% to 35%, empiric prophylaxis should be offered routinely to these patients.24,33,34 STD prophylaxis should be guided by the 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines and includes dispensation of medication for prophylaxis against Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, BV, hepatitis B, and HIV in high-risk cases.24

Table 128.1 includes the 2010 CDC-recommended regimen for STD prophylaxis after a sexual assault. Although the efficacy of these medications in preventing infections after sexual assault has not been evaluated, administration is still considered standard of care given the high single-exposure transmission rate in the case of a disease-positive assailant.24,25

Screening for STDs in asymptomatic sexual assault patients is very controversial. Those in favor of not testing argue that a positive test represents preassault disease and could be used against a victim in court. Laws exist in every state that protect the victim’s previous sexual history, but if medical records are subpoenaed, the STD diagnoses may be discovered. As a result, the patient and clinician might opt to defer testing. The American College of Emergency Physicians states that in cases in which prophylaxis will be given, acute cultures are not necessary unless obvious signs of an STD are present.24,35

Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

The frequency of HIV seroconversion as a result of sexual assault is difficult to estimate but probably low. In consensual sex, the risk for HIV transmission from receptive penile-vaginal intercourse is 0.1% to 0.2% and for receptive penile-rectal intercourse is 0.5% to 3%.26 Various factors increase risk for HIV transmission, including trauma with resultant bleeding, site of exposure to the ejaculate, high viral load in the ejaculate, multiple assailants, and the presence of an STD or genital lesion in either party.24,27

nPEP has not been proved to be effective in decreasing transmission of HIV in cases of sexual assault but, instead, is extrapolated from health care workers with occupational exposure. As a result, a risk-benefit analysis must be performed to determine whether this therapy should be offered. nPEP should be considered only if the exposure occurred less than 72 hours previously, and its efficacy is maximal when administered soonest after exposure.27 Absolute indications for starting nPEP include initial evaluation less than 72 hours after exposure to a known HIV-positive assailant with an exposure that carries substantial risk for transmission. This will rarely be the case because the majority of sexual assault patients do not know the HIV status of their assailant. Consequently, the clinician will have to make a case-by-case determination for starting nPEP based on the characteristics of the assault. The EP should consult with an ID specialist to decide whether therapy is indicated and which regimen would be most appropriate given the assault-specific details. If one is not readily available, assistance with nPEP-related decisions can be obtained by calling the National Clinician’s Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEP line) at (888) 448-4911.24 When the decision is made to administer nPEP, the first dose should be given as soon as possible and prophylaxis continued for 28 days. nPEP is not recommended for patients initially evaluated more than 72 hours after exposure because the risks associated with the medications outweigh the benefits by this time.27 Table 128.1 includes the CDC-recommended regimen for nPEP after a sexual assault.

Prescriptions

As illustrated in Table 128.1, sexual assault patients may be administered multiple medications during the ED visit, the majority of which require only one dose. The exceptions are doxycycline and nPEP. If doxycycline is chosen for Chlamydia prophylaxis, a prescription for a 7-day course should be given. For nPEP, the CDC recommends a 3- to 5-day starter pack to last until the follow-up visit, at which time an additional prescription can be given if appropriate.24,27 If the patient has consumed alcohol in the last 48 hours, she should not be administered metronidazole (Flagyl) in the ED. She should be sent home with the dose or given a prescription so that she can take it when outside the window of a disulfiram-type reaction.

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

After all medical treatment and forensic evaluation are complete, the patient’s environment should be assessed for safety. The SAFE or hospital social worker can help the patient identify resources if she feels unsafe returning home. If deemed safe for discharge, a hospital aftercare packet should be given to the patient because victims of traumatic events frequently cannot remember the events immediately following a crisis. She should be given contact information for the rape crisis center or hospital counseling services because the mental health morbidity associated with sexual assault is profound.32

Within 1 to 5 days of the ED visit, the patient should follow up with an ID specialist for testing for HIV, hepatitis B and C, and syphilis. Additional counseling and support can be offered in addition to assessing for medication adherence and side effects if nPEP was started in the ED. The rest of the 28-day course of medication should then be prescribed or an altered regimen recommended if indicated by side effects. Two weeks after the ED visit the patient should follow up for STD screening. Four weeks after the ED visit the patient should follow up for pregnancy testing and receive the second dose of the hepatitis B vaccine if applicable.24,36

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other non-occupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-2):1–20.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

Green WM. Sexual assault. In: Riviello RJ, ed. Manual of forensic emergency medicine: a guide for clinicians. Boston: Jones & Bartlett; 2010:107.

Scalzo TP. Rape and sexual assault reporting requirements for competent adult victims. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.usmc-mccs.org/famadv/restrictedreporting/National%20Rape%20Reporting%20Requirements%206.15.06.pdf

Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2006. NCJ 210346. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/210346.pdf

1 United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform crime reports. Crime in the United States, 2009: forcible rape. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2009/offenses/violent_crime/forcible_rape.html

2 United States Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice statistics bulletin. Criminal victimization, 2008. September 2009, NCJ 219413. Retrieved January 2011 from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv08.pdf

3 Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2006. NCJ 210346. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/210346.pdf

4 The National Center for Victims of Crime. Sexual violence 2010. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.ncvc.org/ncvc/main.aspx?dbName=DocumentViewer&DocumentID=38719#ftn3

5 Negrusz A, Gaensslen RE. Sexual offenses, adult: drug facilitated sexual assault. In: Payne-James J, Byard RW, Corey TS, et al, eds. Encyclopedia of forensic and legal medicine, vol. 4. Oxford: Elsevier; 2005:107.

6 Crandall CS, Helitzer D. Impact evaluation of a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) program. Unpublished federally funded grant (Award 98-WT-VX-0027). Final report made available by the U.S. Department of Justice. December 2003. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/203276.pdf

7 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Sexual Assault Evidence Collection Kit Forms. Boston: Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety; March 2008.

8 Green WM. Sexual assault. In: Riviello RJ, ed. Manual of forensic emergency medicine: a guide for clinicians. Boston: Jones & Bartlett; 2010:107.

9 Sugar NF, Fine DN, Eckert LO. Physical injury after sexual assault: findings of a large case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:71–76.

10 Riggs N, Houry D, Long G, et al. Analysis of 1,076 cases of sexual assault. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:358–362.

11 Lenahan LC, Ernst A, Johnson B. Colposcopy in evaluation of the adult sexual assault victim. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:183–184.

12 Ramin SM, Satin AJ, Stone IC, Jr., et al. Sexual assault in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:860–864.

13 Bowyer L, Dalton ME. Female victims of rape and their genital injuries. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:617–620.

14 Slaughter L, Brown CR, Crowley S, et al. Patterns of genital injury in female sexual assault victims. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:609–616.

15 Biggs M, Stermac LE, Divinsky M. Genital injuries following sexual assault of women with and without prior sexual intercourse experience. CMAJ. 1998;159:33–37.

16 White C, McLean I. Adolescent complainants of sexual assault: injury patterns in virgins and non-virgin groups. J Clin Forens Med. 2006;13:172–180.

17 Palmer CM, McNulty AM, D’Este C, et al. Genital injuries in women reporting sexual assault. Sex Health. 2004;1:55–59.

18 Hilden M, Schei B, Sidenius K. Genitoanal injury in adult female victims of sexual assault. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;154:200–205.

19 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Sexual Assault Evidence Collection Kit. Form 5B: evidence collected inventory list. Boston: Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety. April 2008.

20 Page S. Forensic evidence in sex offense cases. Boston: MCLE, Inc. Trying sex offense cases in Massachusetts. 2006.

21 Scalzo TP. Rape and sexual assault reporting requirements for competent adult victims. January 11, 2007. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.usmc-mccs.org/famadv/restrictedreporting/National%20Rape%20Reporting%20Requirements%206.15.06.pdf

22 Houry D, Sachs CJ, Feldhaus KM, et al. Violence-inflicted injuries: reporting laws in the fifty states. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:56–60.

23 Bassindale C, Payne-Thomas J. Sexual offenses, adult: injuries and findings after sexual contact. In: Payne-James J, Byard RW, Corey TS, et al, eds. Encyclopedia of forensic and legal medicine, vol. 4. Oxford: Elsevier; 2005:87.

24 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

25 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. Scientific evidence on condom effectiveness for sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention. July 20, 2001. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/organization/dmid/documents/condomreport.pdf

26 Varghese B, Maher JE, Peterman TA, et al. Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:38–43.

27 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other non-occupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-2):1–20.

28 Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, et al. Rape-related pregnancy: estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:320–325.

29 Piaggo G, von Hertzen H, Grimes DA, et al. Timing of emergency contraception with levonorgestrel or the Yuzpe regimen. Lancet. 1999;353:721.

30 von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1803–1810.

31 Cheng L, Gulmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, et al. Interventions for emergency contraception (update of 2004 document). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2008. CD001324

32 Jawad R, Welch J. Sexual offenses, adult: management post-assault. In: Payne-James J, Byard RW, Corey TS, et al, eds. Encyclopedia of forensic and legal medicine, vol. 4. Oxford: Elsevier; 2005:96.

33 Ackerman DR, Sugar NF, Fine DN, et al. Sexual assault victims: factors associated with follow-up care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1653–1659.

34 Parekh V, Brown CB. Follow up of patients who have been recently sexually assaulted. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:349.

35 American College of Emergency Physicians. Evaluation and management of the sexually assaulted or sexually abused patient. Dallas: ACEP; 1999. Retrieved January 2011 from http://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?id=29562

36 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Sexual Assault Evidence Collection Kit. Form 6: Treatment and discharge. Boston: Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety. March 2008.