Chapter 21 Severity Scoring and Outcomes Measurement

Historical Background

With these words from 1775, Patrick Henry set a standard for the role of progress. Moving forward demands a look back and a commitment not to abandon the lessons of the past to the lure of an untested future.1

The approach to accepting change and advancement in medicine and surgical technology is much the same. The promises of the new must meet the expectations built from the experience of the old. The responsibility of the physician is to rigorously evaluate new developments through analysis of data and to share those findings with his or her patients and other physicians.1

There is evidence of the recognition of varicose veins as early as ancient Egyptian and Greek periods, including a familiar tablet in Athens, Greece, of a man displaying a leg with visible varicosities.2 Other writings have offered descriptive accounts of circulation, arteriography and venography, the introduction of heparin, and the embolectomy catheter. From Oribasius in the fourth century, who also wrote about surgical procedures for varicose veins, to Harvey in the 17th century, these writings described in detail the structure and function of the circulatory system.

In an article about the discovery of venous valves, Scultetus et al. wrote: “With the formidable advances of the diagnostic methods and new therapeutic modalities, we will be able to make earlier diagnoses, begin treatment sooner, and increase life expectancy. However, we must not forget the origin of our knowledge—the past.”3

The end of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century have marked a change of focus in venous disease and therapy. Although treatments were regularly being offered for many vascular conditions, the outcomes were only sporadically evaluated. After introducing several valvular reconstructive procedures, Kistner found that reporting methods were not standardized across facilities, preventing interinstitutional trials and confounding results reporting.4 According to Mozes and Gloviczki, “The time has come to standardize the clinical classes of venous disease, to compare treatment and outcome, and to speak the same language when we talk about venous problems all around the world.”5

This realization that the language of diagnostic and treatment information needs to be universal has shifted the focus of physicians to organize information to provide a framework for clinical practice and research.4 Dayal and Kent6 wrote about the need for reporting standards to address important elements of assessment, including clinical classification of disease, a grading system for risk factors, categorization of operations and interventions, complications encountered with grades for severity or outcomes, and criteria for improvement, deterioration, and failure.

Results should be evaluated alongside other options such as the natural course of the disease itself, nonsurgical therapies, additional surgical interventions, or alternative ways of performing an intervention.7 Developing and using proper outcomes assessment tools should be paramount in the minds of those treating venous disease. The assessment of outcomes in chronic venous disease is multifactorial and is more complicated than in other vascular conditions.8 The end points of comparison must be objective usable measures that reflect signs, symptoms, and patient quality of life.9 Rutherford said, “Comparing results is not a simple matter, but if we develop a good, readily usable approach to outcomes comparisons, one by which the results of our labors can be properly judged, the results are great.”7

Etiology and Natural History

In the 1950s, life table analysis was used to examine and predict survival and success rates from many surgical procedures. When the concept was applied to cancer survival in the mid 1970s, it gained acceptance as a valid reporting method for outcomes assessment.10 Reports of short- and long-term survival after procedures for lower extremity ischemia became more common in the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in the 1986 findings of an ad hoc committee of the Society for Vascular Surgery/North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery.11 This group was charged with standardizing reporting practices for lower extremity ischemia. It was one of several subcommittees that met to determine reporting standards for numerous vascular conditions and therapies. Around this same time, reports were being published on clinical outcomes and quality-of-life assessment. Many of the instruments used were able to be applied to the emerging field of venous disease.

The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a generic quality-of-life survey developed from components of multiple surveys used in the 1970s and 1980s. It was first used in a developmental form in 1988 and in a standard form in 1990. It is designed to assess physical health (the patient’s level of functioning) and mental health (an indication of well-being) by breaking these categories into eight domains: physical and social functioning, role limitations because of physical or emotional problems, mental health, pain, vitality, and perception of health. This survey has been widely used and validated in small and large studies, most notably the Bonn Vein Study.11a This German study evaluated 3072 participants and was designed to determine the rate of occurrence and severity of chronic venous disease among the general public. The SF-36 was useful in this study because of its specific objectives. Patients were enrolled from the community without prior knowledge of their venous disease status. By using the reliability and validity of the SF-36 along with physical examinations, it was possible to determine the rate of occurrence of chronic venous disease and its effect on several quality-of-life variables. The International Quality of Life Assessment Project aims to translate and adapt the SF-36 into all major languages. If this undertaking is successful, the SF-36 will gain strength internationally as a measure of health-related quality of life.12,13

In addition to generic measures, patient-reported disease-specific instruments have been used extensively in reporting chronic venous disease and therapy. A patient-reported outcome (PRO) is any report of patient health condition made by the patient and reported as said, without physician interpretation. Such an instrument can be used during the diagnostic phase to measure symptoms or disease states and following therapy to evaluate changes and treatment effect. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends the use of a PRO instrument when the element being measured is best known and expressed by the patient.14

The Chronic Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire (CIVIQ) has had two versions. The first version, CIVIQ 1, was developed in French in 1994, and it was validated in English between 1997 and 1999 in the Reflux Assessment and Quality of Life Improvement with Micronized Flavonoids study.15 The survey evaluated physical, psychological, social, and pain effects. Different numbers of questions were asked in each category, rendering the instrument difficult to score. A revised version, CIVIQ 2, equally distributed the effects across 20 questions to provide a composite score. Both versions of the CIVIQ have been used and validated.12

The Venous Insufficiency Epidemiological and Economic Study (VEINES) instrument was validated in 2006. It consists of 35 items in two categories to generate two summary scores, one for quality of life and another for symptoms. The quality-of-life survey has 25 items that estimate the effect of disease on quality of life, and the symptom survey has 10 items that measure symptoms. The focus is on physical manifestations rather than psychological and social elements. Along with score division into categories of symptoms and disease effect, this makes the VEINES instrument useful for many clinical applications. The VEINES has been validated in four languages.12

The Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire is a 13-question survey developed in 1993 addressing all elements of varicose vein disease. Examined are physical and social issues, including pain, ankle edema, ulcers, and the use of compression therapy as well as the effect of varicose veins on daily life and as a result of cosmetic issues. It is scored from 0 (no effect) to 100 (maximum effect). Specifically addressing the effect of varicose veins on quality of life, including cosmetic impact, this questionnaire was designed to improve the sensitivity of response among all patients, even those with less severe physical symptoms. This survey has been validated and used for all types of venous disease.12,16

The Charing Cross Venous Ulceration Questionnaire was developed and validated in 2000 to provide a quality-of-life measure for patients with venous ulcers. Before the existence of this instrument, there was no standardized measure of the effects of treatment for venous ulcers. The survey contains 20 questions scored from 0 (no effect) to 5 (maximum effect). The instrument is scored from the sum of these individual question scores. It has been validated and used in patients with ulcers.12,17

The Specific Quality of Life and Outcome Response–Venous (SQOR-V) survey was initially validated in French in 2007 and was continuing to undergo validation in English in 2010. It differs from the other patient-reported surveys in its focus on the relationship between the patient’s primary complaint and his or her venous disease. It groups questions regarding symptoms, cosmesis, effect on activities and habits, and worry about the health implications of venous disease. Most of its 15 questions are broken into specific subcategories to elucidate thorough information about each aspect of the patient’s concerns.12,18

The CEAP classification was developed in 1994 as a common descriptive platform for the reporting of diagnostic information in chronic venous disease. The clinical component is scored for active disease severity from 0 (none) to 6 (active ulcers). The etiology section categorizes the venous disease as congenital, primary, or secondary. The anatomic classification identifies affected veins as superficial, deep, or perforating. The pathophysiologic section details the presence or absence of reflux in the superficial, communicating, or deep veins and any incidence of outflow obstruction. The revised CEAP classification, published in 2004, is widely used as the reporting standard in venous disease but is not without drawbacks. Although an excellent descriptive tool, the revised CEAP classification is static and is limited in its ability to reflect response to treatment, especially in the C4 and C5 categories.12 This is most evident if the CEAP classification is used as a stand-alone instrument.

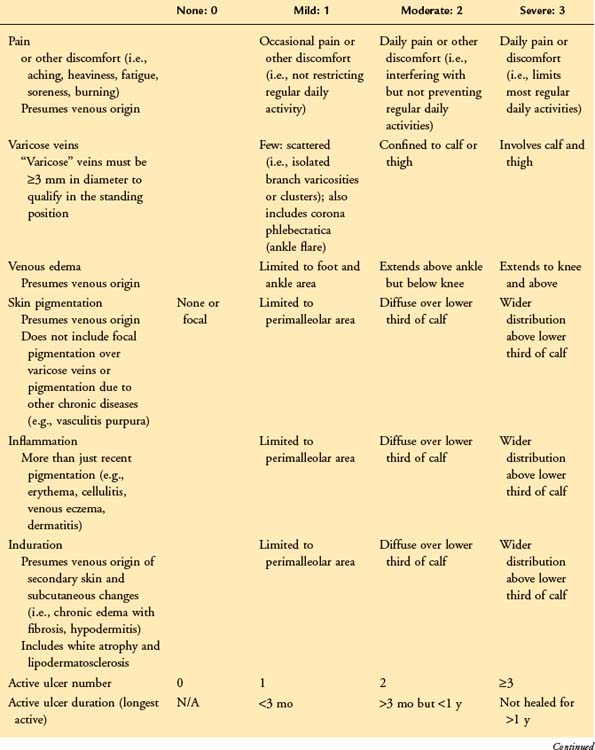

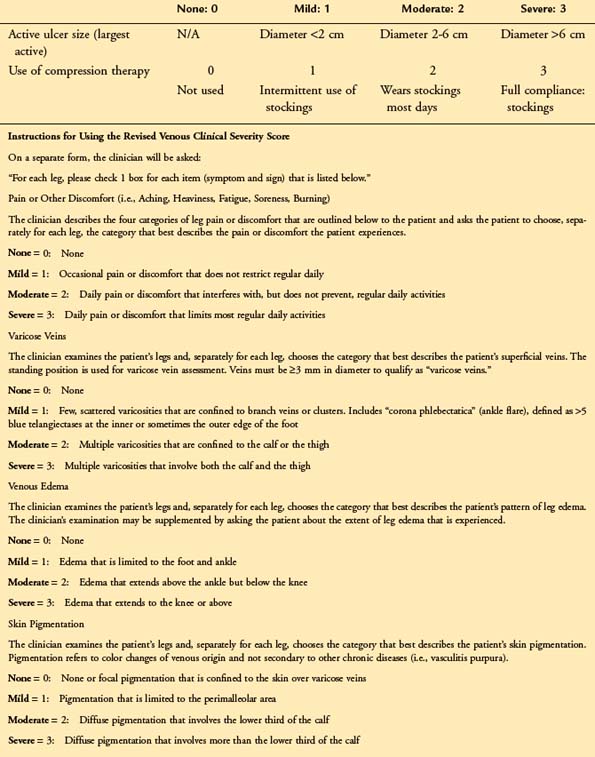

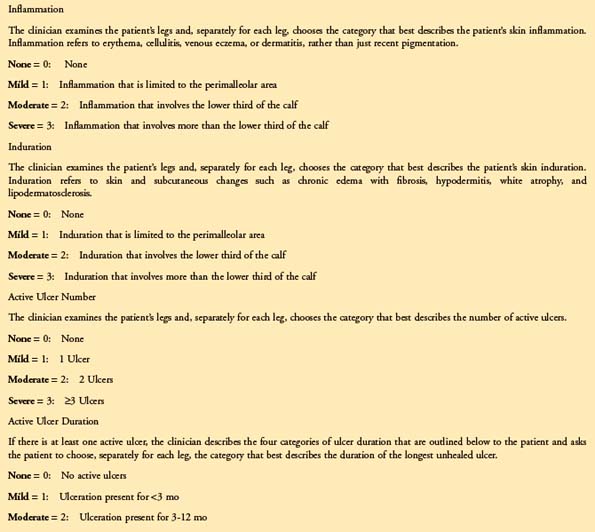

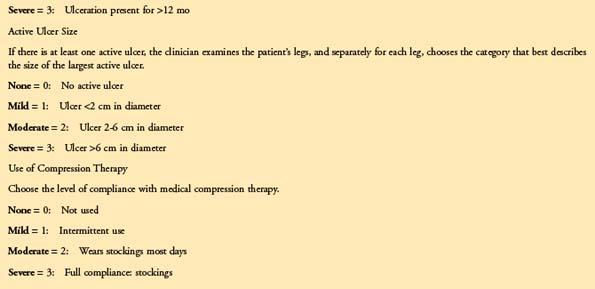

The VCSS was designed in 2000 by a committee of experts to include nine recognized features of venous disease. Each is scored from 0 to 3. The recently revised VCSS19 updates terminology, clarifies application, and combines important language of PROs to reflect severity changes across the spectrum of symptomatic venous disease. The feature that sets the revised VCSS apart from other physician-assessed instruments is its ability to reflect status changes in response to therapy. This is owing to the nature of the categories, which are broken down into elemental aspects of venous disease. The clinical descriptors include vein size and location, the use of compression therapy, skin changes (including pigmentation, inflammation, induration, and ulcers), and edema and its distribution as noted by the patient at different points in the day and by the physician; pain is identified as being “aching, heaviness, fatigue, soreness, and burning.” The revised VCSS is thought to have retained its sensitivity, while better identifying issues of patients with milder venous disease (Table 21-1). The course of outcomes assessment thus far has offered two choices for the type of assessment performed: physician assessed and patient reported. The data derived from physician-assessed instruments may not always be an indication of the effect of disease or the value to the patient of the changes following treatment, even seemingly slight improvements.20,21 However, valuable data can be generated much more readily with little burden to the clinician. Input of these data into available online registries in the United States and in Europe is important to ensure that new therapies meet high standards of safety and reliability and that they address the variables considered important to the physician and the patient.21,22

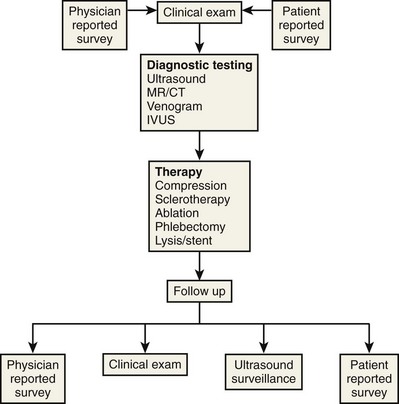

Although physician- and patient-reported tools provide useful information on symptoms and sequelae, the primary difference between them is perspective. It has become evident that some combination of both types of instruments will provide the most comprehensive understanding of common elements. As shown in Figure 21-1, this concept combines the more scientific evidence-based approach of the physician instrument and the focus in the patient-reported assessment on disease elements that are of primary importance to the patient.18,23–25

Regardless of the instrument or approach chosen, the manner in which the data are interpreted and reported is important in evaluating the effect of treatment. It is a long and exacting process for a survey tool to become a valid standardized reporting practice and eventually to evolve into a comprehensive measure of results that is widely accepted in clinical practice and research.4,7

Pearls and Pitfalls

Such surveys must be carefully chosen to address specific elements of the disease state in question. A generic measure such as the SF-36 may not address the specific elements of venous disease that are important to the clinician and patient, while an ulcer-specific survey such as the Charing Cross Venous Ulceration Questionnaire may not reflect the severity of other elements of venous disease. It is more relevant to have assessment instruments that are based on the specific language of venous disease.4 A carefully designed and chosen survey can initially aid in diagnosis and treatment planning. If it is serially applied throughout the treatment process, it can add valuable data on outcomes. When analyzed for a significant relevant population, these outcomes data add to the combined body of knowledge and clinical experience, providing evidence for the best practice treatment of chronic venous disease.26

The selection of outcomes variables to study and report is crucial. Clinical outcomes measure improvement in survival, symptoms, or quality of life as a result of therapy. Surrogate outcomes include diagnostic test results, physical signs, or physiologic variables. Examples include vein occlusion rates following ablation or venous stent patency rates. These often provide quantifiable results during a limited follow-up period. However, it is important to note that surrogate outcomes should not be held to the same standards as clinical outcomes. While the change in response to treatment should still be predictive of benefit to the patient, the relationship between the two outcomes should be clear and well defined. Surrogate outcomes should not simply be correlated with clinical outcomes but should be predictive.26 In our practice, a combination of clinical examination, duplex Doppler study, and the revised VCSS is used to diagnose chronic venous disease and to plan therapeutic intervention. Any of these elements on its own would most likely provide insufficient information to plan a treatment strategy. By integrating all three, a more complete picture is obtained of the clinical severity of the venous disease and the elements that are most important to the patient. This three-spoke strategy helps to guide therapy to achieve a successful outcome for the patient.

Holding assessment instruments to the standard of psychometric analysis ensures the value of tests and their results. Psychometric standards have been used for years to apply standard practices to the development of tests in education, personality analysis, and skill assessment. The benchmarks for a good test are feasibility (whether the test is practical to administer and score), reliability (whether a score can be replicated when the same tester readministers the test), and validity (whether the scores are responsive to change).27

Several generic and disease-specific instruments have been validated psychometrically. The physical and mental health summary measures of the SF-36 are based on the use of psychometric tests, and the instrument itself has been validated in large populations.12 The VEINES instrument has been psychometrically tested in the areas of diagnostic elements (exclusion of classification of anatomic and physiologic variables that might aid choice of treatment) and outcomes scores (whether they could they be scaled and if they accurately delineate clinical significance and degree of change over time).20 The CIVIQ evaluates physical, psychological, social, and pain dimensions and has been validated in large investigations.12 The Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire also measures physical symptoms and social issues but is specific to varicose veins. It has been used with the SF-36 and the VCSS in large studies to assess quality of life at specific intervals following intervention.12 The Charing Cross Venous Ulceration Questionnaire is specific to ulcers and has been used with the SF-36 to measure quality of life in patients with ulcers.12

We have reported on the VCSS as a valuable measure of objective and subjective outcomes in treating chronic venous disease. Others have evaluated the VCSS in large populations, finding it generally useful. Some deficiencies were noted, including the scope of the clinical descriptors used. Because a large part of the VCSS depends on patient responses to physician queries, the ability to interpret the description of symptoms and to match them to a category in the VCSS is crucial in generating accurate data. Can the revised VCSS meet the standard of psychometric evaluation as a valid and reliable assessment tool?12,19,28,29 The VCSS is generated by the clinician on the basis of straightforward questions asked of the patient during examination. There is a combination focus to the instrument. Several categories, including inflammation, induration, pigmentation, ulcers, and veins, are objective and are scored by the physician on the basis of clinical evidence. At the same time, other categories, including pain, edema, and the use of compression hose, are scored based on the subjective responses of the patient. The range of categories covered by the VCSS is representative of chronic venous disease and compiles a more complete picture of quality of life than specialized instruments.12

One of the advantages of the revised VCSS is its ability to provide visual scoring data in chronic venous insufficiency. With the use of revised clinical descriptors, patient-reported symptoms can be combined with physician assessment to more accurately translate the picture of venous disease (Fig. 21-2). This may help to bridge the gap between physician-scored assessment instruments and patient-reported tools and to transport surveys farther into the land of science with standardized language, reliability, and validity.

Refractory unilateral leg swelling can be the result of many factors, including compromise of the muscle pump, venous outflow obstruction, or reflux of the deep, superficial, or perforator systems.30 In conjunction with clinical examination and appropriate testing, the revised VCSS can help to track changes associated with therapy. Unilateral leg swelling that remains after an initial treatment can be further evaluated to rule out other causes and to guide future interventions.

Chronic venous insufficiency without varicose veins may be difficult to discern on initial examination. The use of a survey like the revised VCSS can help to elucidate patient symptoms consistent with underlying venous insufficiency and to guide the rest of the diagnostic process (Fig. 21-3).

Venous ulcers resulting from complex venous insufficiency at multiple levels can be difficult to manage, even with a staged approach to treatment. The revised VCSS can track changes with each therapeutic intervention and provide specific information on the ulcers, including number, size, and duration. This helps to maintain a record of the progress of ulcer healing over time (Fig. 21-4).

Evidence-based medicine and outcomes assessment are critical tools for vascular surgery. The results of high-volume procedures should be followed up with a validated instrument. We found the VCSS and each of its components to be useful, significant, and easily applicable for the assessment of outcomes after radiofrequency ablation in limbs with symptomatic venous insufficiency.29

Comparative Effectiveness of Existing Treatments

Surgical procedures for varicosities have been practiced for centuries, beginning with interventions for ulcers and progressing to surgery on venous valves as understanding about the vascular system grew.4 In 1916, Homans wrote about the relationship between varicose veins and ulcers, at a time when surgical excision of the saphenous vein was being practiced; 20 years later, Linton demonstrated decreased ambulatory venous pressure after ligation of perforating veins, and the widespread treatment of venous disease was under way.4

Endovascular venous ablation is proving to be effective in the long term as part of a strategy to address superficial veins, tributaries, and perforators. Recurrence of clinical symptoms and emergence of new veins are rare in patients treated with ablation, and evaluations performed on the procedure over 5 or more years indicate that it provides a standard of care comparable to saphenous vein stripping.31

The goal of treating venous disease can be very different for the physician versus the patient. While useful, morbidity and mortality statistics report only the direct clinical outcome of an intervention, failing to consider other factors of potential importance to others. For an outcome to be fully evaluated, its effect on the physician, patient, and community must be considered.32 In a quotation attributed to Phaedrus, “Every one is bound to bear patiently the results of his own example.” The physician who is willing to adopt a habit of outcomes assessment and to share those results will be empowered to provide qualified and compassionate care.

1 Gloviczki P. Presidential address: Venous surgery: from stepchild to equal partner. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:871-878.

2 Yao JST. Presidential address: Venous disorders: reflections of the past three decades. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:727-735.

3 Scultetus AH, Villavicencio JL, Rich NM. Facts and fiction surrounding the discovery of the venous valves. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:435-441.

4 Vasquez MA, Munschauer CE. The importance of uniform venous terminology in reports on varicose veins. Semin Vasc Surg. 2010;23:70-77.

5 Mozes G, Gloviczki P. New discoveries in anatomy and new terminology of leg veins: clinical implications. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;38:367-374.

6 Dayal R, Kent KC. Standardized reporting practices. In: Rutherford RB, editor. Vascular Surgery. 6 ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:41-52.

7 Rutherford RB. Presidential address: Vascular surgery: comparing outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23:5-17.

8 Meissner MH, Moneta G, Burnand K, et al. The hemodynamics and diagnosis of venous disease. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:4S-24S.

9 Rutherford RB, Moneta GL, Padberg FT, Meissner MH. Outcome assessment in chronic venous disease. In: Gloviczki P, editor. Handbook of Venous Disorders. London: Hodder Arnold; 2009:684-693.

10 White JV, Jones DN, Rutherford RB. Integrated assessment of results: standardized reporting of outcomes and the computerized vascular registry. In: Rutherford RB, editor. Vascular Surgery. 6 ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:20-37.

11 Rutherford RB, Flanigan DP, Gupta SK, et al. Ad Hoc Committee on Reporting Standards, Society for Vascular Surgery/North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. Suggested standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia [published correction appears in J Vasc Surg 1986;4:350]. J Vasc Surg. 1986;4:80-94.

11a Maurins U, Hoffmann BH, Lösch C, et al. Distribution and prevalence of reflux in the superficial and deep venous system in the general population—results from the Bonn Vein Study, Germany. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:680-687.

12 Vasquez MA, Munschauer CE. Venous Clinical Severity Score and quality-of-life assessment tools: application to vein practice. Phlebology. 2008;23:259-275.

13 Davies AH, Rudarakanchana N. Quality of life and outcome assessment in patients with varicose veins. In: Davies AH, Lees TA, Lane IF, editors. Venous Disease Simplified. Shropshire, England: TFM Publishing Ltd, 2006.

14 US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration; December 2009.

15 Jantet G. Chronic venous insufficiency: worldwide results of the RELIEF study: reflux assessment and quality of life improvement with micronized flavonoids. Angiology. 2002;53:245-256.

16 Garratt AM, Macdonald LM, Ruta DA, et al. Towards measurement of outcome for patients with varicose veins. Qual Health Care. 1993;2:5-10.

17 Smith JJ, Guest MG, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Measuring the quality of life in patients with venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:642-649.

18 Guex JJ, Zimmet SE, Boussetta S, et al. Construction and validation of a patient-reported outcome dedicated to chronic venous disorders: SQOR-V (Specific Quality of Life and Outcome Response–Venous). J Mal Vas. 2007;32:135-147.

19 Vasquez MA, Rabe E, McLafferty RB, et al. Revision of the Venous Clinical Severity Score: Venous outcomes consensus statement: special communication of the American Venous Forum Ad Hoc Outcomes Working Group. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1387-1396.

20 Padberg F. Regarding “Evaluating outcomes in chronic venous disorders of the leg: Development of a scientifically rigorous, patient-reported measure of symptoms and quality of life.”. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:911-912.

21 Lamping DL, Schroter S, Kurz X, et al. Evaluation of outcomes in chronic venous disorders of the leg: Development of a scientifically rigorous, patient-reported measure of symptoms and quality of life. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:410-419.

22 Smith JJ, Garratt AM, Guest M, et al. Evaluating and improving health-related quality of life in patients with varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:710-719.

23 Meissner MH, Natiello C, Nicholls SC. Performance characteristics of the Venous Clinical Severity Score. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:889-895.

24 Kundu S, Lurie F, Millward SF, et al. Recommended reporting standards for endovenous ablation for the treatment of venous insufficiency: joint statement of the American Venous Forum and the Society of Interventional Radiology. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:582-589.

25 White JV. Proper outcomes assessment: patient based and economic evaluations of vascular interventions. In: Rutherford RB, editor. Vascular Surgery. 6 ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:35-41.

26 Meissner MH. “I enjoyed your talk, but …”: Evidence-based medicine and the scientific foundation of the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:244-248.

27 Revicki DA, Cella D, Hays RD, et al. Responsiveness and minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:e70-e74.

28 Vasquez MA. Editor’s corner. AVForum Spring. 2007;1:6-7.

29 Vasquez MA, Wang J, Mahathanaruk M, et al. The utility of the Venous Clinical Severity Score in 682 limbs treated by radiofrequency saphenous vein ablation. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1008-1015.

30 Eberhardt RT, Raffetto JD. Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation. 2005;111:2398-2409.

31 Merchant RF, Pichot O. Long-term outcomes of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration of saphenous reflux as a treatment for superficial venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:502-509.

32 Vasquez MA, Munschauer CE. Clinical and surrogate outcomes from the new radiofrequency catheter: an experience of 700 limbs. In: Greenhalgh R, editor. Vascular and Endovascular Challenges Update. Bodmin, Cornwall, England: MPG Books Ltd; 2010:425-433.