Chapter 63 Severe soft-tissue infections

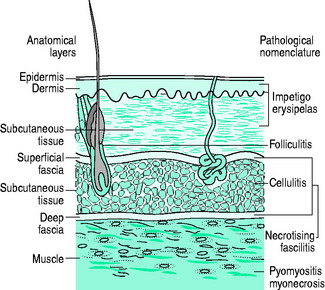

The skin is the largest organ and acts as an excellent barrier against infection. It consists of the epidermis and dermis and resides on fibrous connective tissue, the superficial and deep fasciae (Figure 63.1). The fascial cleft, with nerves, arteries, veins, lymphatic and adipose tissue, lies between these fascial planes. Normal skin flora includes Corynebacterium spp., coagulase-negative staphylococci, Micrococcus spp., Lactobacillus and, rarely, Staphylococcus aureus. Colonisation by Gram-negative bacteria occurs in hospital patients; once altered, skin flora includes a higher proportion of S. aureus which ultimately becomes pathogenic.

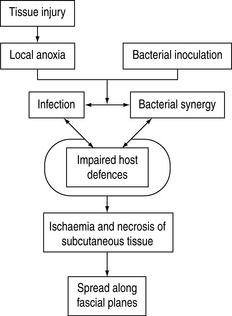

These colonising microorganisms seldom cause skin and soft-tissue infections, but serious infections can occur if: there is a break in the skin because of traumatic lesion or maceration; soft tissues are ischaemic and non-viable; colonising bacteria are particularly virulent; or the patient is immunocompromised (Figure 63.2).1–9 Conditions predisposing to infection include diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, malnutrition, major trauma, advanced age, renal failure, steroid use, collagen vascular disease and malignancies.1–10 Differentiation between soft-tissue infections can be difficult and one unified management approach to severe forms is appropriate.11–13 Management decisions are further based on likely causative organism, depth of infection and clinical severity.8

Soft-tissue infections are usually caused by bacterial entry through skin lesions or perforation of adjacent intestinal structures. Skin lesions can on occasion be the manifestations of systemic infection; examples of this are bacteraemia by meningococci, staphylococci, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida spp., and bacterial endocarditis.3 These will not be specifically addressed here.

CLASSIFICATION

The bacteriology and subtypes of severe soft-tissue infections have not changed significantly over the last century.8,14–16 Community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), however, can be seen as an emerging cause of severe tissue infection with a high prevalence in certain parts of the world.17–19 The classification of soft-tissue infections can be confusing, partly because individual organisms can cause different clinical syndromes. Consequently, there are a wealth of terms often referring to the same diseases (e.g. Meleney’s gangrene, haemolytic streptococcal gangrene and progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene).14 Classification by the anatomical structure involved is more logical, but it has to be borne in mind that some conditions involve several soft-tissue levels and that some cases may evolve froma minor entity to a more severe form with more diffuse anatomical involvement (see Figure 63.1).

IMPETIGO

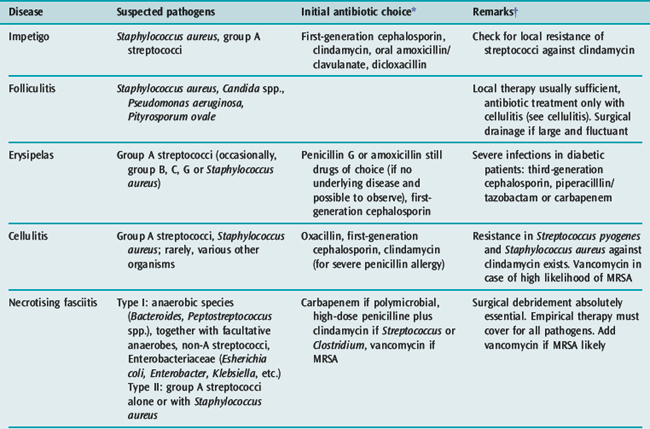

Impetigo,1–3 more common in children, is a superficial skin infection caused by group A streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, or both. Mild infections can be managed with topical antibiotics; more serious infections need a first-generation cephalosporin. A penicillinase-resistant penicillin is mostly chosen in severe empirical conditions (e.g. dicloxacillin).20 Increasing resistance in streptococci and staphylococci might prohibit the use of erythromycin, which has been the alternative in the penicillin-allergic patient. For community-acquired MRSA, co-trimoxazole is an alternative.

FOLLICULITIS

This is an infection arising in hair follicles and apocrine glands.2,3 S. aureus is the usual causative organism. Topical antibiotic treatment is usually all that is required. When confluent, folliculitis can evolve to furunculosis and may need surgical drainage as sole effective therapy. If accompanied by cellulitis and/or sepsis, antibiotics are added (see section on cellulitis). Repeated folliculitis raises the possibility of chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited immunodeficiency syndrome based on granulocyte malfunction.21 Affected individuals are at risk for severe soft-tissue infections, sometimes with rare pathogens such as Aspergillus spp.

ERYSIPELAS

This superficial dermal infection is largely caused by group A streptococci and also by other streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus.1–3,8,9 The prominent lymphatic blockade results in a painful bright red patch with a raised sharp border, which clearly demarcates the infection from normal surrounding skin. Fever and chills often precede the skin eruption. Predisposing conditions include ulcers, venous stasis, diabetes, alcoholism and paraparesis. High-dose penicillin is still the drug of choice in the absence of underlying disease and the possibility to observe the evolution of the lesion. Severe infections in diabetic patients require a third-generation cephalosporin, piperacillin-tazobactam or a carbapenem. If mobilisation is premature, signs recur and treatment failure may falsely be suspected. However, recurrent erysipelas does occur with persistent lymphoedema.

CELLULITIS

Cellulitis1,2,3,5–9,22 is an acute spreading infection of the skin extending below the superficial fascia, usually involving only the upper part of the subcutaneous tissue. It can occur at any body site, but is most frequent in the lower extremities and in the face. There is less lymphatic involvement so the borders of the infection are often not well defined and differentiation between cellulitis and erysipelas is sometimes difficult. Fever, malaise and rigors are common. It is more common in patients with tissue oedema. Cellulitis is most commonly due to Streptococcus pyogenes, but other Gram-positive and negative organisms can also cause this condition according to location and exposure history.9

Typically, S. pyogenes cellulitis may appear hours after surgical intervention with fast progression of the erythematic zone over a large surface and can be accompanied by bacteraemia and sepsis. Many of these organisms may produce gas, hence crepitus is sometimes present (Table 63.1).

| Cellulitis | Usually anaerobic organisms, clostridial and non-clostridial |

| Bursitis | Gram-negative organisms |

| Necrotising fasciitis | Usually type I (mixed infections, Gram-negative organisms) |

| Myonecrosis | Clostridial organisms |

| Infected vascular gangrene | Any organism |

A severe and fulminant form of cellulitis with hemorrhagic bullous lesions can be caused by marine bacteria of the Vibrio spp., mostly with a history of contact with sea-water or raw fish.23 After fresh-water exposure of wounds24 or application of medical leeches,25Aeromonas hydrophilia is a possible aetiology.

TREATMENT

Appropriate microbiological tests are undertaken prior to starting antibiotics. Any skin abrasion or sites that drain are swabbed for Gram stain and culture. Needle aspiration, skin biopsy and blood cultures produce only a 25% positive yield.1 Treatment involves site elevation and high-dose oxacillin or a first-generation cephalosporin. If there is a possibility of MRSA, vancomycin is indicated instead. In severe cases, the addition of clindamycin is beneficial because of its antitoxic effect and enhanced intracellular activity.26 If Gram-negative rods are suspected or identified (e.g. an immunocompromised patient or involvement of intestinal tract lesions), a third-generation cephalosporin should be considered. In a patient with prolonged hospitalisation or in penetrating foot infections, a cephalosporin with anti-Pseudomonas activity is preferred. If Vibrio spp. are suspected or isolated, doxycycline may be added. In the absence of controlled studies, some authors recommend ceftazidime27,28 in addition to tetracyclines because of the high mortality of 50%.23

Pyoderma gangrenosum has a similar appearance, but a completely different aetiology and therapeutic management. It is a rare idiopathic, infiammatory, ulcerative disease of undetermined cause that is more frequent in patients with ulcerative colitis and rheumatoid arthritis and presents as deep ulcers with undermined borders, usually on the lower extremities or abdomen. It is often triggered by surgical intervention and only secondarily colonised with skin flora. Treatment is conservative and includes steroid medication.29

NECROTISING FASCIITIS

Necrotising fasciitis1,2,3,5–8,10–13,30–35 is a deeper infection of the skin with extensive undermining of surrounding tissues. Interest in this fulminant infection has recently increased.14,30,36 The World Health Organization reports only 160 cases since 1989, but the incidence in the USA is about 100 cases annually and recently there has been an increased incidence of group A streptococcal fasciitis in Europe.14,30

It usually occurs on the extremities, perineum and abdominal wall. Involvement of male genitalia is known as Fournier’s gangrene.15 Two types are described, depending on causative organisms.33 Type I are mixed infections usually caused by Gram-positive and negative aerobe and anaerobe bacteria or Vibrio spp. Type II infections are caused by group A streptococci (occasionally with Staphylococcus aureus). Secondary infections with zygomycetes may occur.32,34 There is no difference in the clinical course, morbidity and mortality between the two types of infection.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A history of minor trauma is common and necrotising fasciitis can complicate surgery and varicella infections.30,37 Predisposing factors include cirrhosis, diabetes and other immunocompromised states. Necrotising fasciitis begins as an area of cellulitis that typically fails to improve on antibiotics and quickly spreads. Pathophysiological sequelae of sepsis result in microthrombi and impaired, leading to gangrene. Pain is a predominant feature and frequently out of keeping with other presenting symptoms and signs. Sometimes no external sign is apparent and increasing pain may even be the only initial symptom. Fever, rigors and shock are common.30 Half of the cases of necrotising fasciitis present together with a streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome.20 Manifestations of the systemic infiammatory response syndrome are evident and multiple-organ dysfunction develops in most cases. Bullae may form, and late lesions may resemble deep burns that are painfree because of the necrosis of nerve fibres. Reduced skin surface sensitivity and elevated creatine phosphokinase may suggest fascial involvement. Crepitus may be present (see Table 63.1). The normally adherent fascia may be easily peeled off the underlying muscle bed.

Retroperitoneal necrotising fasciitis is particularly vicious, with a high mortality due partly to the difficulty in diagnosis.38 Abdominal or perineal trauma or sepsis is always the predisposing event. Diagnosis can only be made at laparotomy for the presenting acute abdomen. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and aggressive surgery (repeated debridement of all necrotic tissue) with planned ‘relook’ laparotomies are strongly suggested.

Necrotising fasciitis concerning the face, eyelid or lip are rather of type II, whereas that of the neck is more often of type I and associated with a fourfold mortality compared to the facial form.39

MANAGEMENT

Because of rapid progression, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for the prognosis. Two major diagnostic tools are appropriate. We recommend that a highly experienced surgeon in the treatment of necrotising fasciitis be involved as early as possible with surgical incision, probing of fascial consistency and histological diagnosis on a frozen-section specimen of doubtful fascia intraoperatively.40 The other mainstay of diagnosis is MRI. Recently, a score has been proposed to discriminate between necrotising and non-necrotising severe soft-tissue infections based on a set of six laboratory results.41

A complete microbiological investigation is of the utmost importance. This includes sampling for culture by needle aspiration of any crepitant area and blood cultures. Treatment with antibiotics alone is usually inadequate. Immediate extensive surgical removal of necrotic and damaged tissues is essential.11,12,30–32,34 Planned surgery at 24-hour intervals to debride spreading necrotic tissue is necessary until the necrotic process stops. If extremities are involved, amputation may be life-saving.

Initial antibiotic therapy includes a carbapenem or a third-generation cephalosporin plus clindamycin while awaiting Gram stain and culture results. Clindamycin 600 mg intravenously 6-hourly is added because of toxin inhibition and anaerobic activity.26 If fungi (e.g. mucormycosis) are isolated, amphotericin B 0.5 mg/kg per day intravenously should be given for at least 2 weeks.32,34 As in cellulitis, Vibrio spp. are treated with both a third-generation cephalosporin and tetracycline.27

PYOMYOSITIS AND MYONECROSIS

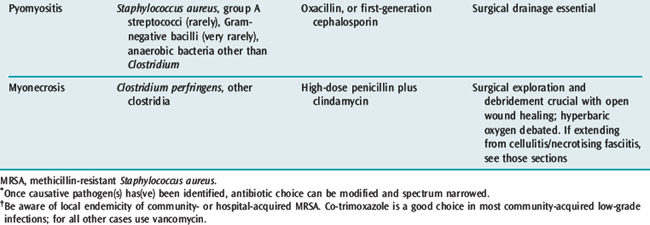

Muscles are remarkably resistant to infection so bacterial infections are rare. Pyomyositis is a focal infection usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Myonecrosis is caused by Clostridium spp. or various other bacteria when it evolves from cellulitis.1,2,4–7,11,12,31,32,35,42–44 Bacteria might act synergistically and often produce various toxins (Figure 63.2).4,32 As infection is likely to be mixed, differentiation of pyomyositis and myonecrosis is bacteriological, and only important for antibiotic choices.

PYOMYOSITIS

Pyomyositis is more common in the tropics. The causative organism in over 90% of cases is S. aureus, with others being Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli and S. pneumoniae. Pyomyositis often follows blunt trauma to torso, thigh or buttock muscles. Spontaneous staphylococcal muscle abscesses may occasionally occur.2 Initial presentation is with aching muscles which feel indurated on examination. If untreated, the muscles become erythematous and boggy and are eventually destroyed. Spontaneous drainage of debris and pus does not occur. Instead, there is contiguous spread to surrounding tissues and metastatic spread to the chest (e.g. empyemas) and heart (e.g. endocarditis and pericarditis).

Investigations include needle biopsy (for Gram stain of the aspirate), ultrasound (for localised muscle oedema) and, more recently, MRI.2 Large increases in serum creatine phosphokinase may be indicative of the degree of muscle involvement.44 Antibiotic therapy with a penicillinase-resistant penicillin or a first-generation cephalosporin may be successful in the early stages. More often, though, the condition is not recognised early because of diagnostic difficulties and extensive surgical drainage becomes necessary for a favourable outcome.44 Even after disfiguring muscle destruction, functional prognosis is good.

MYONECROSIS

The bacterial infection of muscles by clostridial organisms (usually Clostridium perfringens or C. septicum) has been called gas gangrene as crepitus may occur. However, other causes of skin crepitus are just as common (see Table 63.1). Predisposing causes are contaminated wounds (e.g. in trauma and septic abortions) and surgery in immunocompromised patients.

A Gram stain revealing Gram-positive rods of Clostridium is diagnostic. Treatment of myonecrosis involves prompt, extensive surgical debridement of all infected tissue and antibiotics (i.e. high-dose penicillin plus clindamycin).2 At surgery, the muscle is pale or brick-coloured and does not bleed. Hyperbaric oxygen has its proponents45,46 and may be beneficial in conjunction with good supportive care. However, there is no prospective evidence to support the use of hyperbaric oxygen.47

SPECIAL AREAS OF SOFT-TISSUE INFECTION

NECK INFECTIONS

Since the advent of antibiotics, oropharyngeal infections are no longer major causes of neck infections.48–50 Dental infection and regional trauma are now more common causes. Neck infections include Ludwig’s angina, retropharyngeal abscesses, parapharyngeal abscesses and necrotising cervical fasciitis. Ludwig’s angina is a submandibular-space infection. There is deep and tender swelling of the submandibular and submaxillary area, with swelling of the fioor of the mouth and elevation of the tongue.

Neck X-rays usually demonstrate some abnormality. CT or MRI will define anatomy and may help to decide on a course of conservative, expectant therapy.50 Oesophagoscopy should be performed on all retropharyngeal abscesses, as foreign-body ingestion is a possible predisposing event.

Airway control must take top priority in any neck swelling. Antibiotics, in doses similar to necrotising fasciitis, should incorporate cover for Gram-positive cocci and Gram-negative rods. Penicillin or clindamycin plus gentamicin, or a third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole, are suitable. Some abscesses may be treated conservatively, especially those in children.50 However, early surgical drainage remains the mainstay of management for large neck abscesses that impinge on airway patency, or deep infections that pursue a fulminant course.

Retrotonsillar abscess may evolve to Lemierre’s syndrome, an infection with anaerobic bacteria, mostly Fusobacterium necrophorum, that gain access to the jugular vein and lead to metastatic infections in the liver, lung and brain. Because of possible involvement of anaerobes that produce beta-lactamase, a beta-lactamase-resisting beta-lactam antibiotic should be used.51

1 Conly J. Soft tissue infections. In: Hall JB, Schmidt GA, Wood LDH, editors. Principles of Critical Care. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992:1325-1334.

2 Canoso JJ, Barza M. Soft tissue infections. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1993;19:293-309.

3 Swartz MN. Cellulitis and subcutaneous tissue infections. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th edn. New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2004:1172-1194.

4 Pasternack M, Swartz M. Myositis. In: Mandell GL, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th edn. New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2004:1194-1204.

5 Ahrenholz DH. Necrotising fasciitis and other soft tissue infections. In: Rippe JM, Irwin RS, Alpert JS, et al, editors. Intensive Care Medicine. Boston: Little, Brown; 1991:1334-1342.

6 Cha JY, Releford BJJr, Marcarelli P. Necrotising fasciitis: a classification of necrotising soft tissue infections. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994;33:148-155.

7 Sutherland ME, Meyer AA. Necrotising soft-tissue infections. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:591-607.

8 Vinh DC, Embil JM. Rapidly progressive soft tissue infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:501-513.

9 Swartz MN. Clinical practice. Cellulitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:904-912.

10 Ward RG, Walsh MS. Necrotising fasciitis: 10 years’ experience in a district general hospital. Br J Surg. 1991;78:488-489.

11 Kaiser RE, Cerra FB. Progressive necrotising surgical infections – a unified approach. J Trauma. 1981;21:349-355.

12 Freischlag JA, Ajalat G, Busuttil RW. Treatment of necrotising soft tissue infections. The need for a new approach. Am J Surg. 1985;149:751-755.

13 Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotising soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:705-710.

14 Loudon I. Necrotising fasciitis, hospital gangrene, and phagedena. Lancet. 1994;344:1416-1419.

15 Fournier AJ. Clinical study of fulminating gangrene of the penis. Semin Med. 1884;4:69.

16 Meleney FL. Hemolytic streptococcus gangrene. Arch Surg. 1924;9:317-319.

17 Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Meticillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:666-674.

18 Fridkin SK, Hageman JC, Morrison M, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1436-1444.

19 Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Rieg G, et al. Necrotising fasciitis caused by community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Los Angeles. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1445-1453.

20 Bisno AL, Stevens DL. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:240.

21 Lekstrom-Himes JA, Gallin JI. Immunodeficiency diseases caused by defects in phagocytes. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1703-1714.

22 Stevens DL. Cellulitis, pyoderma, abcesses and other skin and subcutaneous infections. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, editors. Infectious Diseases. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004:145-155.

23 Morris JGJr, Black RE. Cholera and other vibrioses in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:343-350.

24 Hiransuthikul N, Tantisiriwat W, Lertutsahakul K, et al. Skin and soft-tissue infections among tsunami survivors in southern Thailand. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:e93-96.

25 Sartor C, Limouzin-Perotti F, Legre R, et al. Nosocomial infections with Aeromonas hydrophila from leeches. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:e1-5.

26 Russell NE, Pachorek RE. Clindamycin in the treatment of streptococcal and staphylococcal toxic shock syndromes. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:936-939.

27 Bowdre JH, Hull JH, Cocchetto DM. Antibiotic efficacy against Vibrio vulnificus in the mouse: superiority of tetracycline. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;225:595-598.

28 Chuang YC, Yuan CY, Liu CY, et al. Vibrio vulnificus infection in Taiwan: report of 28 cases and review of clinical manifestations and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:271-276.

29 Bennett ML, Jackson JM, Jorizzo JL, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. A comparison of typical and atypical forms with an emphasis on time to remission. Case review of 86 patients from 2 institutions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:37-46.

30 Chelsom J, Halstensen A, Haga T, et al. Necrotising fasciitis due to group A streptococci in western Norway: incidence and clinical features. Lancet. 1994;344:1111-1115.

31 Baxter CR. Surgical management of soft tissue infections. Surg Clin North Am. 1972;52:1483-1499.

32 Patino JF, Castro D. Necrotising lesions of soft tissues: a review. World J Surg. 1991;15:235-239.

33 Giuliano A, Lewis FJr, Hadley K, et al. Bacteriology of necrotising fasciitis. Am J Surg. 1977;134:52-57.

34 Patino JF, Castro D, Valencia A, et al. Necrotising soft tissue lesions after a volcanic cataclysm. World J Surg. 1991;15:240-247.

35 Stevens DL. Necrotising fasciitis, gas gangrene, myoxitis and myonecrosis. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, editors. Infectious Diseases. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2004:145-155.

36 Burge TS, Watson JD. Necrotising fasciitis. Br Med J. 1994;308:1453-1454.

37 Wilson GJ, Talkington DF, Gruber W, et al. Group A streptococcal necrotising fasciitis following varicella in children: case reports and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1333-1338.

38 Mokoena T, Luvuno FM, Marivate M. Surgical management of retroperitoneal necrotising fasciitis by planned repeat laparotomy and debridement. S Afr J Surg. 1993;31:65-70.

39 Banerjee AR, Murty GE, Moir AA. Cervical necrotising fasciitis: a distinct clinicopathological entity? J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:81-86.

40 Stamenkovic I, Lew PD. Early recognition of potentially fatal necrotising fasciitis: use of frozen-section biopsy. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1689.

41 Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, et al. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotising Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotising fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1535-1541.

42 Ahrenholz DH. Necrotising soft-tissue infections. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:199-214.

43 Stone HH, Matin JD. Synergistic necrotising cellulitis. Ann Surg. 1972;175:702-710.

44 Hird B, Byne K. Gangrenous streptococcal myositis: case report. J Trauma. 1994;36:589-591.

45 Kingston D, Seal DV. Current hypotheses on synergistic microbial gangrene. Br J Surg. 1990;77:260-264.

46 Brown DR, Davis NL, Lepawsky M, et al. A multicenter review of the treatment of major truncal necrotising infections with and without hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Am J Surg. 1994;167:485-489.

47 Heimbach D. Use of hyperbaric oxygen. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:239-240.

48 Sethi DS, Stanley RE. Deep neck abscesses – changing trends. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:138-143.

49 Linder HH. The anatomy of the fasciae of the face and neck with particular reference to the spread and treatment of intraoral infections (Ludwigs’s) that have progressed into adjacent fascial spaces. Ann Surg. 1986;204:705-714.

50 Broughton RA. Nonsurgical management of deep neck infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:14-18.

51 Sinave CP, Hardy GJ, Fardy PW. The Lemierre syndrome: suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein secondary to oropharyngeal infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989;68:85-94.