Chapter 677 Septic Arthritis

Etiology

Historically, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Chapter 186) accounted for more than half of all cases of bacterial arthritis in infants and young children. Since the development of the conjugate, it is now a rare cause; Staphylococcus aureus (Chapter 174.1) has emerged as the most common infection in all age groups. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus accounts for a high proportion (>25%) of community S. aureus isolates in many areas of the USA and throughout the world. Group A streptococcus (Chapter 176) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) (Chapter 175) historically cause 10-20%; S. pneumoniae is most likely in the first 2 years of life. Kingella kingae is recognized as a relatively common etiology with improved culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods in children <5 yr old (Chapter 676). In sexually active adolescents, gonococcus (Chapter 185) is a common cause of septic arthritis and tenosynovitis, usually of small joints or as a monoarticular infection of a large joint (knee). Neisseria meningitidis (Chapter 184) can cause either a septic arthritis that occurs in the first few days of illness or a reactive arthritis that is typically seen several days after antibiotics have been initiated. Group B streptococcus (Chapter 177) is an important cause of septic arthritis in neonates.

A microbial etiology is confirmed in about 65% of cases of septic arthritis. Prior antibiotic therapy and the inhibitory effect of pus on microbial growth might explain the low bacterial yield. Additionally, some cases treated as bacterial arthritis are actually postinfectious (gastrointestinal or genitourinary) reactive arthritis (Chapter 151) rather than primary infection. Lyme disease produces an arthritis more like a rheumatologic disorder and not typically suppurative.

Clinical Manifestations

Most septic arthritides are monoarticular. The signs and symptoms of septic arthritis depend on the age of the patient. Early signs and symptoms may be subtle, particularly in neonates. Septic arthritis in neonates and young infants is often associated with adjacent osteomyelitis caused by transphyseal spread of infection, although osteomyelitis contiguous with an infected joint can be seen at any age (Chapter 676).

Joints of the lower extremity constitute 75% of all cases of septic arthritis (Table 677-1). The elbow, wrist, and shoulder joints are involved in about 25% of cases, and small joints are uncommonly infected. Suppurative infections of the hip, shoulder, elbow, and ankle in older infants and children may be associated with an adjacent osteomyelitis of the proximal femur, proximal humerus, proximal radius, and distal tibia because the metaphysis extends intra-articularly.

| BONE | % |

|---|---|

| Knee | ∼40 |

| Hip | 22-40 |

| Ankle | 4-13 |

| Elbow | 8-12 |

| Wrist | 1-4 |

| Shoulder | ∼3 |

| Interphalangeal | <1 |

| Metatarsal | <1 |

| Sacroiliac | <1 |

| Acromioclavicular | <1 |

| Metacarpal | <1 |

| Toe | ∼1 |

Modified from Gafur OA, Copley LA, Hollmig ST, et al: The impact of the current epidemiology of pediatric musculoskeletal infection on evaluation and treatment guidelines, J Pediatr Orthop 28:777–785, 2008.

Diagnosis

Radiographic Evaluation

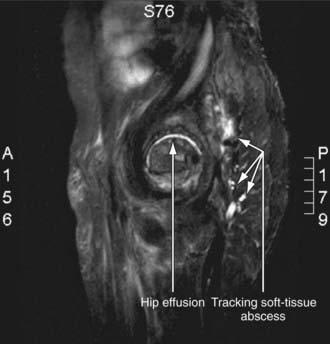

Radiographic studies play a crucial role in evaluating septic arthritis. Conventional radiographs, ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and radionuclide studies can all contribute to establishing the diagnosis (Fig. 677-1).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of septic arthritis depends on the joint or joints involved and the age of the patient. For the hip, toxic synovitis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, psoas abscess, and proximal femoral, pelvic, or vertebral osteomyelitis as well as diskitis should be considered. For the knee, distal femoral or proximal tibial osteomyelitis, pauciarticular rheumatoid arthritis, and referred pain from the hip should be considered. Other conditions such as trauma, cellulitis, pyomyositis, sickle cell disease, hemophilia, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura can mimic purulent arthritis. When several joints are involved, serum sickness, collagen vascular disease, rheumatic fever, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura should be considered. Arthritis is one of the extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Reactive arthritis following a variety of bacterial (gastrointestinal or genital) and parasitic infections, streptococcal pharyngitis, or viral hepatitis can resemble acute septic arthritis (Chapter 151).

Arnold SR, Elias D, Buckingham SC, et al. Changing patterns of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:703-708.

Bonheffer J, Haeberle B, Schaad UB, et al. Diagnosis of hematogenous osteomyelitis and septic arthritis: 20 years experience at the University Children’s Hospital Basel. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001;131:575-581.

Carrillo-Marquez M, Hulten KG, Hammerman WA, et al. USA300 is the predominant genotype causing Staphylococcus aureus septic arthritis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:1076-1080.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Osteomyelitis/septic arthritis caused by Kingella kingae among day care attendees—Minnesota. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;53:241-243.

Cheer K, Pearce S. Osteoarticular infection of the symphysis public and sacroiliac joints in active young sportsmen. BMJ. 2010;340:362-364.

Dubnov-Raz G, Scheuerman O, Chodick G, et al. Invasive Kingella kingae infections in children: clinical and laboratory characteristics. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1305-1309.

Harel L, Prais D, Bar-On E, et al. Dexamethasone therapy for septic arthritis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(2):211-215.

Howard A, Wilson M. Septic arthritis in children. BMJ. 2010;341:776-777.

Kang SN, Sanghera T, Mangwani J, et al. The management of septic arthritis in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1127-1133.

Matthews CJ, Weston VC, Jones A, et al. Bacterial septic arthritis in adults. Lancet. 2010;375:846-854.

Nelson JD. Bugs, drugs and bones: a pediatric infectious disease specialist reflects on management of musculoskeletal infections. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19:141-142.

Odio CM, Ramirez T, Arias G, et al. Double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of dexamethasone therapy for hematogenous septic arthritis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:883-888.

Peltola H, Paakkonen M, Kallio P, et al. Prospective, randomized trial of 10 days versus 30 day of antimicrobial treatment, including a short-term course of parenteral therapy, for childhood septic arthritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1201-1210.

Ross JJ, Hu LT. Septic arthritis of the pubic symphysis. Medicine. 2003;82:340-345.

Saavedra-Lozano J, Mejías A, Ahmed N, et al. Changing trends in acute osteomyelitis in children: impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:569-575.

Schirtliff ME, Mader JT. Acute septic arthritis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:527-554.

Sultan J, Hughes PJ. Septic arthritis or transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1289-1293.

Taekema HC, Landham PR, Maconochie I. Towards evidence based medicine for paediatricians. distinguishing between transient synovitis and septic arthritis in the limping child: how useful are clinical prediction tools? Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:167-168.

Wang CL, Wang SM, Yang YJ, et al. Septic arthritis in children: relationship of causative pathogens, complications, and outcome. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36:41-46.