172 Sepsis

• Sepsis encompasses a spectrum of diseases: infection with signs of a systemic inflammatory response, severe sepsis, and septic shock.

• Treatment in the emergency department includes early, presumptive administration of antibiotics and early, aggressive fluid resuscitation, with the use of central venous pressure monitoring and vasopressors when appropriate to optimize resuscitation.

• Patients with severe sepsis and septic shock must be monitored closely and should be admitted to an intensive care unit.

Epidemiology

In the United States alone, more than 750,000 cases of sepsis occur, and approximately 215,000 deaths result from this disease annually.1 Over the 25-year period between 1972 and 1997, little change occurred in the mortality rate (ranging from 40% to >60%) for patients with septic shock.2 More recent advances in the early treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock have shown improvements in mortality and thus promise for patients and their treating physicians.3–5

Pathophysiology

Sepsis is defined as a condition in which an identified or suspected source of infection leads to a systemic inflammatory process, known as the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (Box 172.1). Severe sepsis refers to sepsis that has progressed to cellular dysfunction and organ damage or evidence of hypoperfusion, whereas septic shock refers to sepsis with persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation. SIRS can develop when an exaggerated response of the body’s immune system to infection results in the release of inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6) as the immune cells encounter the organisms’ endotoxins.6 These cytokines can lead to activation of the coagulation cascade with subsequent thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, as well as the release and activation of nitric oxide, thought to be the key mediator in vasodilation and shock.4,7 Progression of shock can lead to poor oxygen delivery and use at the tissue level, thereby creating an environment in which lactic acid is generated and mixed venous oxygenation is impaired.

Box 172.1 Definition of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

The presence of two or more of the following four items constitutes sepsis:

• Temperature lower than 36° C or higher than 38° C

• Heart rate greater than 90 beats per minute

• Respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths per minute or partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide lower than 32 mm Hg

• White blood cell count lower than 4000 or higher than 12,000 cells/mm3 or more than 10% bands

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

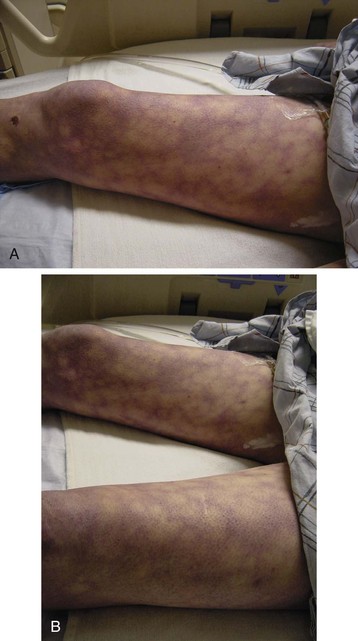

The patient with classic severe sepsis or septic shock appears ill, with fever (less commonly hypothermia) and chills, an increased respiratory rate, and tachycardia. Patients may have cold skin showing outward signs of decreased perfusion (Fig. 172.1), and they may have mental status changes.

The presentation may or may not direct the clinician to the potential source of infection. For example, dyspnea and crackles on a lung examination may point to a pneumonia source, or left lower quadrant tenderness on an abdominal examination may point to diverticulitis as the source. Determining the site of infection in the emergency department (ED) may be difficult, and even retrospectively, an initial source is not determined in up to 15% of patients (Box 172.2).8

More objective measures (SIRS criteria, lactate level, mixed venous oxygenation) are used to determine whether a patient has sepsis because patients can sometimes appear surprisingly well even when they have severe sepsis or septic shock. Their only complaint may be fever, even though other SIRS criteria and hypotension may be present, especially in relatively younger, healthier, immunocompetent patients (see Fig. 172.1).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The diagnostic work-up may vary among patients, but most patients require standard testing to start. Serum lactate has become an important risk stratification tool because both the initial serum lactate level and lactate clearance have been shown to be important predictors of mortality.9,10 Further work-up should be guided by the suspected source of infection. For example, concern about a possible abdominopelvic infection (e.g., diverticulitis, acute cholecystitis) may warrant a computed tomography scan of the abdomen or pelvis or a right upper quadrant ultrasound scan, whereas concern about a possible central nervous system infection (e.g., meningitis) may warrant lumbar puncture. A procalcitonin level determination may be helpful in guiding therapy and predicting outcomes, whereas future molecular assays may help in more rapid identification of pathogens.11,12 The diagnostic evaluation is important, but aggressive treatment in advance of test results is essential.

Treatment

Intubation may be necessary to provide airway protection (i.e., for decreased mental status) or to decrease the work of breathing and improve oxygenation. Etomidate causes measurable, albeit transient, adrenal suppression (see Chapter 168), but the use of a single dose of etomidate as an induction agent in the ED to facilitate rapid-sequence intubation remains clinically indicated.13 Corticosteroids can be considered in patients with persistent hypotension unresponsive to fluids.

Sepsis Bundles

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement developed recommendations for early, initial treatment of the patient with severe sepsis or septic shock (Box 172.3).14 These recommendations are based on the best current available evidence from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign’s management guidelines.15

Box 172.3

Institute for Healthcare Improvement Sepsis Resuscitation Bundle

B. Blood cultures obtained before antibiotic administration

C. Antibiotics administered within 3 hours of emergency department presentation

D. In the event of hypotension or lactate greater than 4 mmol/L (36 mg/dL):

E. In the event of persistent hypotension despite fluid resuscitation or lactate greater than 4 mmol/L (36 mg/dL):

From Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Sepsis. 2011. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/Sepsis.

Antimicrobial Therapy

Patients should receive antibiotic coverage, early and presumptively. Coverage should be directed at the source, if known, but broad-spectrum antibiotics are generally advisable. Early administration of adequate antibiotics favors improved outcomes, whereas delays in administration result in increased mortality for this patient population.16,17

Early Goal-Directed Therapy

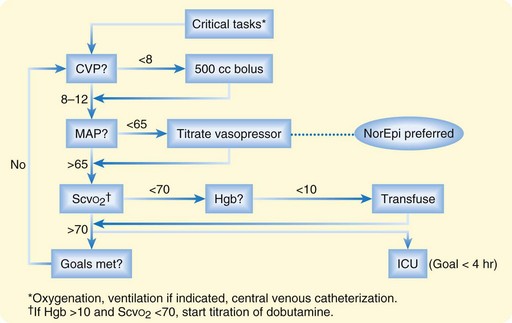

Early goal-directed therapy has generated great interest and is influencing treatment for patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.3 Mortality is reduced by early identification of patients with severe sepsis (identified as patients with lactic acid >4 mmol/L) or septic shock (identified as patients with systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg after 20 to 30 mL/kg of fluid) and by early aggressive hemodynamic monitoring and optimization using specific resuscitation end points (central venous pressure, mean arterial pressure, mixed venous oxygen saturation). Early goal-directed therapy is summarized in Figure 172.2.

Vasopressors

In patients with persistent hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 65 mm Hg or systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg) despite initial fluid resuscitation (20 to 30 mL/kg), vasopressors should be used to maintain organ perfusion. First-line agents include norepinephrine, at 2 to 20 mcg/minute, or dopamine, at 5 to 20 mcg/kg/minute.15 Norepinephrine (Levophed) may improve survival in patients with septic shock who require vasopressor therapy, and this agent may be better at correcting hypotension while avoiding potential arrhythmias more commonly seen with dopamine.18,19 Vasopressin, at 0.01 to 0.04 units/minute, can be considered as an additional agent in patients with hypotension refractory to initial vasoactive medications because it appears to have synergistic effects.20 Other second-line agents include phenylephrine and epinephrine.

Low-Dose Corticosteroids and Activated Protein C

In addition to being less conducive to administration in the ED, low-dose corticosteroids and activated protein C have limited scope, and their use continues to be debated.4,5,21,22 In a large, multicenter trial, corticosteroids were not shown to improve survival and were also associated with an increased risk of superinfection.21 Shock was reversed more rapidly with corticosteroids when reversal was achieved, and previous studies showed improved survival.5 Corticosteroids can still be considered in patients poorly responsive to fluids and vasopressors.15 If given, corticosteroids can be administered in the form of intravenous hydrocortisone (200 to 300 mg/day as a continuous infusion or as 50-mg boluses). Adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation testing is not necessary.

De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:779–789.

Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327.

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377.

Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D, et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:524–528.

Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–124.

1 Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310.

2 Friedman G, Silva E, Vincent JL. Has the mortality of septic shock changed with time? Crit Care Med. 1998;26:2078–2086.

3 Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377.

4 Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699–709.

5 Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862–871.

6 Bone RC, Grodzin CJ, Balk RA. Sepsis: a new hypothesis for pathogenesis of the disease process. Chest. 1997;112:235–243.

7 Vincent JL, Zhang H, Szabo C, Preiser JC. Effects of nitric oxide in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1781–1785.

8 Bernard GR, Reines HD, Halushka PV, et al. The effects of ibuprofen on the physiology and survival of patients with sepsis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:912–918.

9 Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D, et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:524–528.

10 Arnold RC, Shapiro NI, Jones AE, et al. Multicenter study of early lactate clearance as a determinant of survival in patients with presumed sepsis. Shock. 2009;32:35–39.

11 Georgopoulou AP, Savva A, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, et al. Early changes of procalcitonin may advise about prognosis and appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy in sepsis. J Crit Care. 2011;26:331.e1–331.e7.

12 Tenover FC. Rapid detection and identification of bacterial pathogens using novel molecular technologies: infection control and beyond. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:418–423.

13 Ray DC, McKeown DW. Effect of induction agent on vasopressor and steroid use, and outcome in patients with septic shock. Crit Care. 2007;11:R56.

14 Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Sepsis. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/Sepsis, 2011.

15 Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327.

16 Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1589–1596.

17 Garnacho-Montero J, Aldabo-Pallas T, Garnacho-Montero C, et al. Timing of adequate antibiotic therapy is a greater determinant of outcome than are TNF and IL-10 polymorphisms in patients with sepsis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R111.

18 Martin C, Papazian L, Perrin G, et al. Norepinephrine or dopamine for the treatment of hyperdynamic septic shock? Chest. 1993;103:1826–1831.

19 De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:779–789.

20 Dunser MW, Mayr AJ, Ulmer H, et al. Arginine vasopressin in advanced vasodilatory shock: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Circulation. 2003;107:2313–2319.

21 Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–124.

22 Abraham E, Laterre PF, Garg R, et al. Drotrecogin alpha (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1332–1341.