Chapter 28 Sensory Abnormalities of the Limbs, Trunk, and Face

Anatomy and Physiology

Sensory Transduction

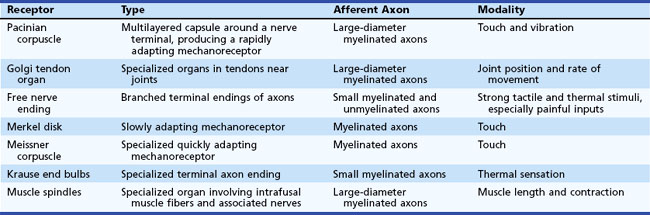

Sensory transducers are seldom directly affected by neuropathic conditions, although peripheral vascular disease can produce dysfunction of the skin sensory axons, and systemic sclerosis can damage skin sufficiently to produce a primary deficit of sensory transduction (Table 28.1).

Sensory Afferents

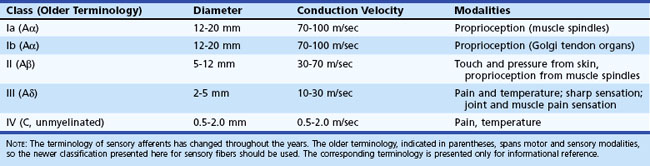

The rate of action potential propagation differs according to the diameter of the axons and depending on whether the fibers are myelinated or unmyelinated. In general, nociceptive afferents are small myelinated and unmyelinated axons. Non-nociceptive afferents are large-diameter myelinated axons. Afferent fiber characteristics are shown in Table 28.2.

Spinal Cord Pathways

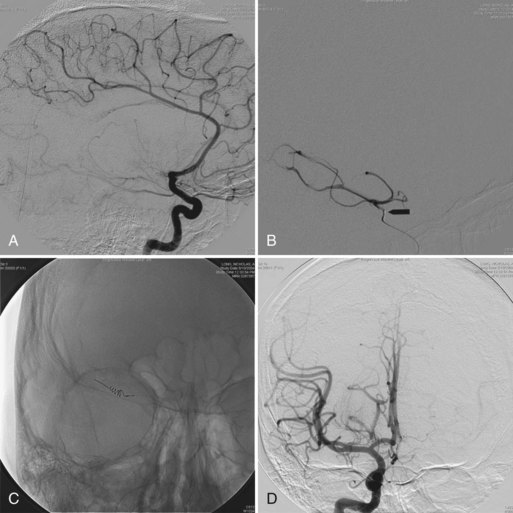

The dorsal column tracts ascend to the cervicomedullary junction, where axons from the leg synapse in the nucleus gracilis and axons from the arms synapse in the nucleus cuneatus. Fig. 28.1 shows the ascending pathways through the spinal cord to the brain.

Brain Pathways

Cerebral Cortex

Classic neuroanatomical teaching presents a picture of the central sulcus bounded by the motor strip anteriorly and the sensory strip posteriorly. This division was derived largely from study of lower animals, in which the separation between these functions is marked. On ascending the evolutionary ladder, however, this division becomes less prominent, and many neurologists refer to the entire region as the motor-sensory strip. In general, sensory function is served prominently on the postcentral gyrus. The mapping of the cortex follows the same homunculus presented in Chapter 23 (see Fig. 23.1), with the head and arm portions located laterally on the hemisphere and the leg region located superiorly near the midline and wrapping onto the parasagittal cortex.

Sensory Abnormalities

Neuropathic pain can result from damage of any cause to the sensory nerves. Peripheral neuropathic conditions result in failure of conduction of the sensory fibers, giving decreased sensory function plus pain from discharge of damaged nociceptive axons. The pathophysiology of neuropathic pain is interesting. Part of its basis is lowering of the membrane potential of the axons so that minor deformation of the nerve can produce repetitive action-potential discharges (Zimmermann, 2001). An additional feature with neuropathic conditions appears to be membrane potential instability, so that the crests of fluctuations of membrane potential can produce action potentials. Finally, cross-talk (ephaptic transmission) between damaged axons allows an action potential in one nerve fiber to be abnormally transmitted to an adjacent nerve fiber. These pathophysiological changes also produce exaggerated sensory symptoms including hyperesthesia and hyperpathia. Hyperesthesia is increased sensory experience with a stimulus. Hyperpathia is augmented painful sensation.

Localization of Sensory Abnormalities

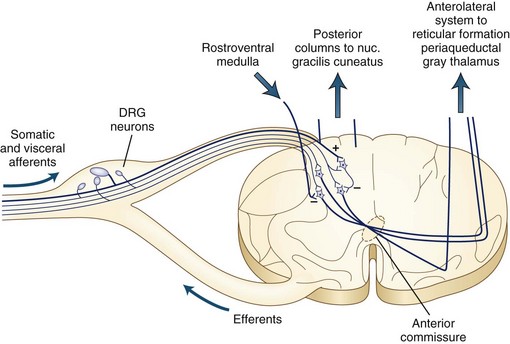

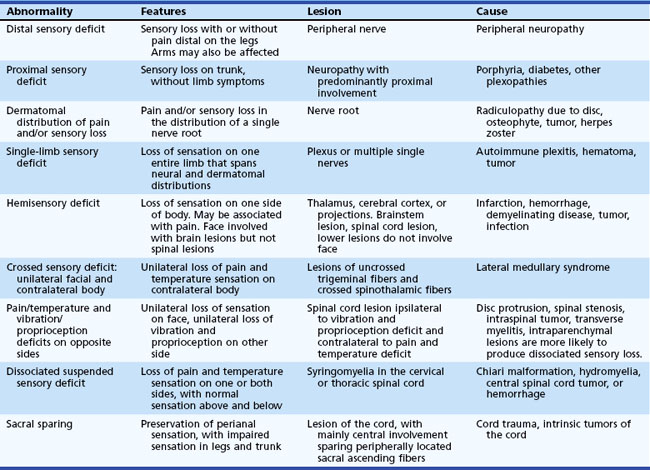

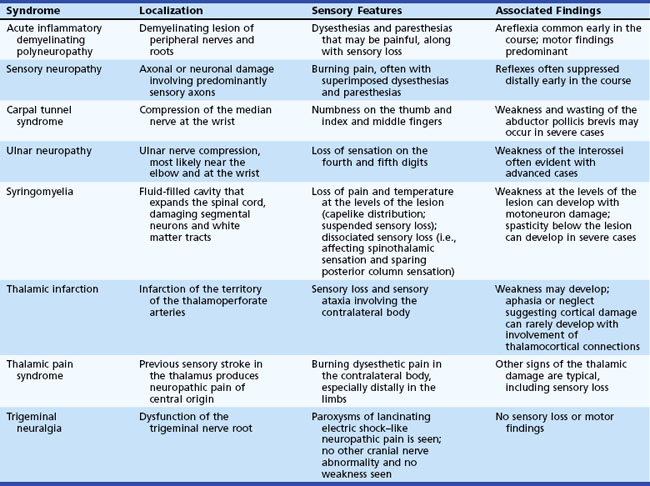

A general guide to sensory localization is presented in Table 28.3. Guidelines for diagnosis of these sensory abnormalities are summarized in Table 28.4. Details of specific sensory levels of dysfunction are discussed next.

| Level of Lesion | Features and Location of Sensory Loss |

|---|---|

| Cortical | Sensory loss in contralateral body restricted to portion of the homunculus affected by lesion. If entire side is affected (with large lesions), either the face and arm or the leg tends to be affected to a greater extent. |

| Internal capsule | Sensory symptoms in contralateral body which usually involve head, arm, and leg to an equal extent. Motor findings common, although not always present. |

| Thalamus | Sensory symptoms in contralateral body including head. May split midline. Sensory dysfunction without weakness highly suggestive of lesion of the thalamus. |

| Spinal transaction | Sensory loss at or below a segmental level, which may be slightly different for each side. Motor examination also key to localization. |

| Spinal hemisection | Sensory loss ipsilateral for vibration and proprioception (dorsal columns), contralateral for pain and temperature (spinothalamic tract). |

| Nerve root | Sensory symptoms follow dermatomal distribution. |

| Plexus | Sensory symptoms span two or more adjacent root distributions, corresponding to anatomy of plexus divisions. |

| Peripheral nerve | Distribution follows peripheral nerve anatomy or involves nerves symmetrically. |

Peripheral Sensory Lesions

Distal sensory loss and/or pain in more than one limb suggests peripheral neuropathy.

Distal sensory loss and/or pain in more than one limb suggests peripheral neuropathy.

Sensory loss in a restricted portion of one limb suggests a peripheral nerve or plexus lesion, and mapping of the deficit should make the diagnosis.

Sensory loss in a restricted portion of one limb suggests a peripheral nerve or plexus lesion, and mapping of the deficit should make the diagnosis.

Sensory loss affecting an entire limb seldom is due to a peripheral lesion, because even proximal plexus lesions rarely affect the entire limb. A central lesion should be sought.

Sensory loss affecting an entire limb seldom is due to a peripheral lesion, because even proximal plexus lesions rarely affect the entire limb. A central lesion should be sought.

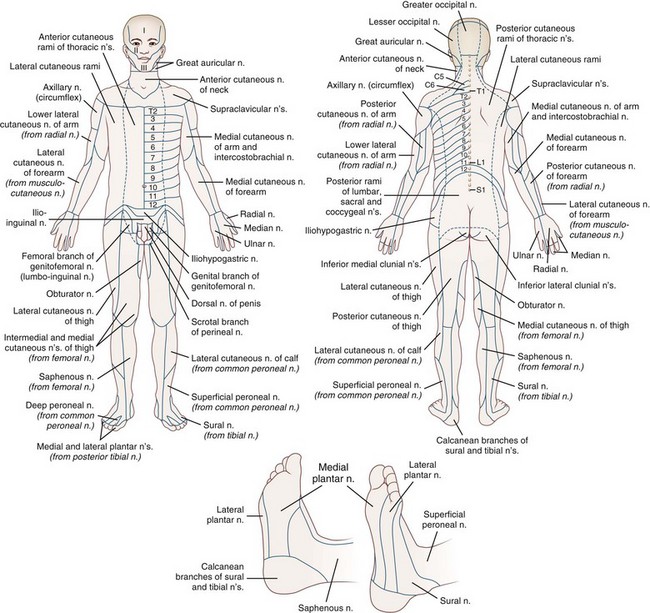

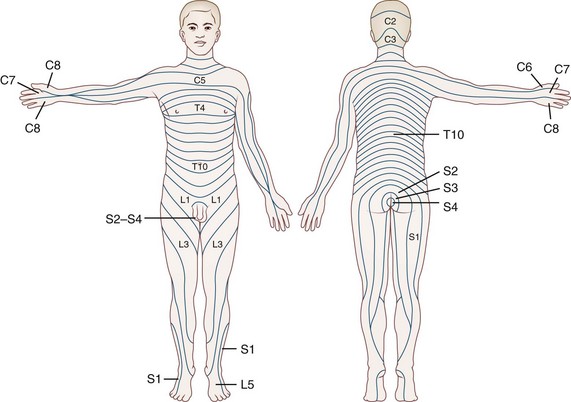

Fig. 28.2 summarizes the peripheral nerve anatomy of the body, and Fig. 28.3 shows the dermatomal distribution.

Spinal Sensory Lesions

Certain sensory syndromes suggest a spinal lesion:

Sensory Level

Although a spinal cord localization is suspected with a sensory level, the level of the sensory loss may be slightly different between the two sides; this finding does not indicate a second lesion. Also, a basic tenet of neurology for evaluation of spinal sensory levels is to look for a lesion not only at the upper level of the deficit but also higher. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best noninvasive test for assessing sensory loss of spinal origin. Of note, demyelinating disease and other inflammatory conditions of the spinal cord may not be visualized on MRI, although if an inflammatory lesion is suspected, a contrasted study on a high-field scanner has greater diagnostic sensitivity (Runge, Muroff, and Jinkins, 2001).

Suspended Sensory Loss

A third form of dissociated sensory loss with loss of pain and temperature sensation, sparing of touch and joint-position sensation (usually affecting the upper limbs), and normal sensation above and below the lesion is seen in syringomyelia (see Syringomyelia, later).

Common Sensory Syndromes

Some common sensory syndromes are outlined in Table 28.5. Many of these are associated with motor deficits as well.

Peripheral Syndromes

Sensory Polyneuropathy

Nerve conduction studies can evaluate the status of the myelin sheath, thereby identifying patients with predominantly demyelinating polyneuropathies, including acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). Electromyography (EMG) can demonstrate denervation and hence axonal damage, thereby identifying the motor involvement of many neuropathies with predominantly axonal features (Misulis and Head, 2002).

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome–Associated Neuropathies

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection can produce a variety of neuropathic presentations. One of the most common is a painful, predominantly sensory polyneuropathy (Robinson-Papp and Simpson, 2009). The diagnosis can be confirmed by nerve conduction studies, EMG, and the appropriate clinical findings. CSF analysis and biopsy usually are not necessary unless an HIV-1–associated vasculitis or infection (such as cytomegalovirus) is present.

Toxic Neuropathies

Some toxic neuropathies can be predominantly sensory. Such presentations most commonly are seen in patients with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez et al., 2010). Although motor abnormalities do occur, the sensory symptoms eclipse the motor symptoms for most patients. Development of dysesthesias, burning, and loss of sensation is the characteristic presentation. The neuropathy can be severe enough to be dose limiting for some patients and may continue to progress for months after cessation of chemotherapy administration, after which time some recovery is expected.

Amyloid Neuropathy

Primary amyloidosis can produce a predominantly sensory neuropathy in approximately one third of affected patients (Simmons and Specht, 2010). Familial amyloid polyneuropathy is a dominantly inherited condition. Patients present with painful dysesthesias plus loss of pain and temperature sensation. Weakness develops later. Autonomic dysfunction is typical. Eventually the sensory loss can be severe enough to make the affected extremities virtually anesthetic. The diagnosis can be suspected on clinical grounds, and confirmation requires positive results on either DNA genetic testing or nerve biopsy. Findings on nerve conduction studies and the EMG are not specific.

Proximal Sensory Loss

Proximal sensory loss involving the trunk and upper aspects of the arms and legs is uncommon but can be seen in patients with porphyria or diabetes and in some patients with proximal plexopathies with a restricted distribution. Other rare causes of proximal sensory loss include Tangier disease, Sjögren syndrome, and paraneoplastic syndrome (Rudnicki and Dalmau, 2005). These neuropathic processes can be associated with pain in addition to the sensory loss. Motor deficit also is common, with weakness in a proximal distribution.

Temperature-Dependent Sensory Loss

Leprosy can produce sensory deficits that predominantly affect cooler regions of the skin including the fingers, toes, nose, and ears (Wilder-Smith and Van Brakel, 2008). Temperature sensation initially is impaired, with subsequent involvement of pain and touch sensation in the cooler skin regions. The deficit gradually ascends to warmer areas, typically in a stocking-glove distribution, with frequent trigeminal and ulnar nerve involvement. The diagnosis of leprosy is suggested by these findings and can be confirmed by additional testing including assay for antibodies to phenolic glycolipid-I (PGL-I) and nerve biopsy.

Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP), or Guillain-Barré syndrome, is an autoimmune process characterized by rapid progression of inflammatory demyelination of the nerve roots and peripheral nerves. Patients present with generalized weakness that may spread from the legs upwards or occasionally from cranial motor nerves downwards. Sensory symptoms generally are overshadowed by the motor loss. Tendon reflexes are lost as the weakness progresses (Hughes and Cornblath, 2005).

Mononeuropathy

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Compression of the median nerve at the wrist produces sensory loss on the palmar aspects of the first through the third digits. Motor symptoms and signs can develop with increasing severity of the mononeuropathy, but the sensory symptoms predominate, especially early in the course. Weakness and wasting of the abductor pollicis brevis can develop (Bland, 2005).

Ulnar Neuropathy

Ulnar neuropathy is commonly due to compression in the region of the ulnar groove. Patients present with numbness in the ulnar two fingers (fourth and fifth digits). Weakness of the interossei develops with advanced ulnar neuropathy in any location, but sensory symptoms predominate, especially early in the course (Cut, 2007).

Radiculopathy

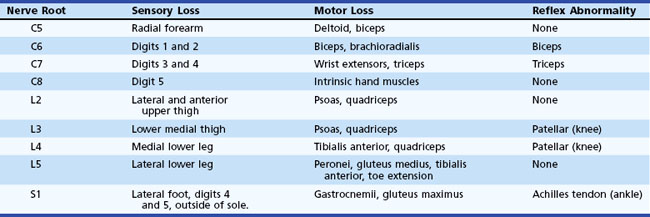

Table 28.6 presents clinical features of common radiculopathies. Although cervical and lumbar radiculopathies are discussed here, any level can be affected. Diabetic radiculopathy and herpes zoster commonly affect thoracic dermatomes, as well as cervical and thoracic dermatomes usually unaffected by spondylosis or disk disease.

Spinal Syndromes

Myelopathy

Some basic “pearls” regarding sensory testing in patients with suspected myelopathy follow:

A defined line-like level is not expected.

A defined line-like level is not expected.

The sensory mapping is not as precise as that shown on dermatome charts.

The sensory mapping is not as precise as that shown on dermatome charts.

The sensory loss is seldom complete, which makes precise localization even more difficult.

The sensory loss is seldom complete, which makes precise localization even more difficult.

The sensory level may not be at the same level on the two sides of the body—a discrepancy of up to several levels can be seen.

The sensory level may not be at the same level on the two sides of the body—a discrepancy of up to several levels can be seen.

Look for dissociated sensory loss due to crossed projections of pain/temperature versus uncrossed touch/proprioception projections.

Look for dissociated sensory loss due to crossed projections of pain/temperature versus uncrossed touch/proprioception projections.

Discrepancy in sensory level between posterior column and spinothalamic levels can occur because of intersegmental projections of the axons of the posterolateral (Lissauer) tract.

Discrepancy in sensory level between posterior column and spinothalamic levels can occur because of intersegmental projections of the axons of the posterolateral (Lissauer) tract.

The sensory level may be much higher than might be expected from motor examination or pain. This is because the lesion may be much higher than indicated by the levels of clinical findings, reinforcing the basic precept that the examiner must start from the level of the symptoms and look up!

The sensory level may be much higher than might be expected from motor examination or pain. This is because the lesion may be much higher than indicated by the levels of clinical findings, reinforcing the basic precept that the examiner must start from the level of the symptoms and look up!

Syringomyelia

Syringomyelia is the presence of a syrinx, or fluid-filled space, in the spinal cord that extends over several to many segments. This is most commonly associated with a Chiari malformation (Koyanagi and Houkin, 2010). The pathogenic theory is that partial obstruction to CSF flow plus pressure waves in the CSF result in rupture of the central canal into the parenchyma of the spinal cord, which then produces symptoms by mechanical effects. The mass effect of the syrinx produces damage to the fibers crossing in the anterior commissure that are destined for the spinothalamic tract, which conveys pain and temperature sensation. With more severe enlargement of the syrinx, damage to the surrounding ascending tracts may occur, affecting sensation below the level of the lesion. By the time this develops, segmental motoneuron damage and descending corticospinal tract damage are almost always present, and clinical signs of these changes can be seen.

Brain Syndromes

Thalamic Pain Syndrome (Central Post-Stroke Pain)

Thalamic pain syndrome is an occasional sequela to thalamic infarction that usually affects the entire contralateral body, from face through arm, trunk, and leg. The pain, mainly distal in the limbs, is present at rest but is exacerbated by sensory stimulation. The distribution of the pain may shift so that the pain is poorly localized (Nicholson, 2004). Sensory detection thresholds are increased. Involvement of the posterior ventrobasal region is thought to be necessary for production of thalamic pain.

The term central post-stroke pain syndrome is increasingly used, since not all post-stroke pain syndromes are due to primary thalamic damage, although the thalamus is still felt to be an important part of the pathophysiology (Klit, Finnerup, and Jensen, 2009).

Functional (or Psychogenic) Sensory Loss

Bland J.D. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:581-585.

Cut S. Cubital tunnel syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:28-31.

Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez G., Sereno M., Miralles A., et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: clinical features, diagnosis, prevention and treatment strategies. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010 Feb;12(2):81-91.

Hughes R.A., Cornblath D.R. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 2005 Nov 5;366(9497):1653-1666.

Klit H., Finnerup N.B., Jensen T.S. Central post-stroke pain: clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2009 Sep;8(9):857-868.

Koyanagi I., Houkin K. Pathogenesis of syringomyelia associated with Chiari type 1 malformation: review of evidences and proposal of a new hypothesis. Neurosurg Rev. 2010 Jul;33(3):271-284.

Marra C.M. Update on neurosyphilis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009 Mar;11(2):127-134.

Misulis K.E., Head T.C. Essentials of Clinical Neurophysiology, third ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2002.

Nicholson B.D. Evaluation and treatment of central pain syndromes. Neurology. 2004;62(Suppl. 2):30-36.

Robinson-Papp J., Simpson D.M. Neuromuscular diseases associated with HIV-1 infection. Muscle Nerve. 2009 Dec;40(6):1043-1053.

Rudnicki S.A., Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic syndromes of the peripheral nerves. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:598-603.

Runge V.M., Muroff L.R., Jinkins J.R. Central nervous system: review of clinical use of contrast media. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2001 Aug;12(4):231-263.

Simmons Z., Specht C.S. The neuromuscular manifestations of amyloidosis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2010 Mar;11(3):145-157.

Wilder-Smith E.P., Van Brakel W.H. Nerve damage in leprosy and its management. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008 Dec;4(12):656-663.

Zimmermann M. Pathobiology of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429:23-37.