196 Self-Harm and Danger to Others

• Risk factors that increase the likelihood of self-harm include depression and other mental disorders, alcohol or substance abuse, separation or divorce, physical or sexual abuse, and significant medical conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus infection, cancer, and dialysis-dependent renal failure.

• Psychiatric illness and substance abuse increase the likelihood of homicidal ideation.

• Although adolescent and young adult female patients are more likely to be treated in the emergency department after a suicidal gesture, older men are more likely to commit suicide.

• In the United States, all 50 states provide physicians the legal right to commit any patient who is a threat to either self or others.

• Health professionals are required to inform individuals directly if they are at risk for harm from a homicidal patient. Police should also be notified of such risk.

• Any patient discharged from the emergency department after appropriate psychiatric evaluation should agree to immediately seek medical care if thoughts of violence or self-harm return.

Epidemiology

Patients with suicidal or homicidal ideation are encountered frequently in the emergency department (ED). Approximately 0.4% of all ED visits in the United States involve suicidal patients, and suicide accounted for 34,598 deaths in 2007 (almost twice the number of deaths by homicide, 18,361), which makes it the 10th leading cause of death overall.1 For Americans aged 15 to 24 years, suicide ranks as the third leading cause of death.2 This age group also accounts for more ED visits for attempted suicide and self-injury than any other age group does. More than 1200 children and adolescents complete suicide annually in the United States,3 and it is estimated that 11 attempted suicides occur per suicide death.1 More than 40% of individuals 16 years or older who completed suicide were evaluated in an ED in the year before their terminal act.3

Although the rate of attempted suicide was highest in female patients 15 to 19 years old, nearly five times as many males died by suicide in this age group. About six times as many males as females died by suicide in the 20- to 24-year age group, and older, non-Hispanic white men have a suicide rate than is staggeringly higher than the national average for the general population. Of patients with evidence of self-harm, poisoning was the cause of death in 13% of males and 40% of females, suffocation in 24% of males and 21% of females, and firearms in 56% of males and 30% of females.1 Self-mutilation (by cutting or piercing) was observed in 20% of patients evaluated in the ED for a suicidal gesture. One third of suicidal patients were admitted for inpatient management, one third were transferred to an off-site facility, and one fifth were referred to outpatient psychiatric services.4

Intentionally harmful behavior also constitutes a growing problem in children, adolescents, and young adults. It has been estimated that the prevalence of mental illness among youth in Canada and the United States approaches 15% to 20%, with an anticipated 50% increase by 2020. Pediatric mental health complaints account for 1.6% of all annual ED visits in the United States and 1% of all annual ED visits in Canada.2,5

Homicide ranks as the most common cause of death in black males 15 to 24 years of age and is the second leading cause of deaths for all youths in this age group. In 2005 alone, more than 5000 deaths by homicide occurred in this age group, and in 2006 this age group received medical care for more than 750,000 cases of nonfatal violent injury.6

Pathophysiology

Numerous factors influence the likelihood of self-harm, including depression and other mental disorders, alcohol or substance abuse, separation or divorce, physical or sexual abuse, and significant medical conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus infection, cancer, and dialysis-dependent renal failure (see the “Red Flags” box). Previous suicide attempters also have more concurrent general medical conditions, alcohol or substance abuse, work hours missed, and current suicidal ideation than do nonattempters.7 More than 90% of people who die by suicide have a mental health disorder, a substance abuse disorder, or both.1 Depression is a significant and common risk factor to address because one in three patients encountered in the ED have moderate to severe depression. In adult male ED patients, depression is more strongly associated with the likelihood of perpetrating violent behavior than excessive alcohol consumption is.8

Besides the presence of risk factors, poorly understood biologic factors probably influence self-harm. Serotonin levels have been studied in suicidal patients, and data suggest that lower levels of cerebral 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (a serotonin metabolite) are found in patients who attempt suicide.9–11 Increasing serotonin levels through pharmacotherapy with drug classes such as tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors is a common treatment of depression and suicidal ideation.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Trauma incongruent with an accident (single-car motor vehicle crash, pedestrians struck by a vehicle)

Intoxicated or altered patients

History of mental illness, especially depression or schizophrenia

History of alcohol or substance abuse

Family history of suicide, mental disorders, or substance abuse

Family history of child maltreatment, including physical or sexual abuse

Impulsive or aggressive tendencies

Barriers to accessing mental health treatment

Loss (relationship, work, financial)

Physical illness (especially human immunodeficiency virus infection, cancer, end-stage renal disease)

Easy access to lethal methods (stored pills, firearms)

Unwillingness to seek help because of stigma attached to mental illness, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation

Data from American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. November 2003. Available at http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/prac_guide.cfm; and Villeneuve P, Holowaty E, Brisson J, et al. Mortality among Canadian women with cosmetic breast implants. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:334–41.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

In addition, emergency physicians should be cognizant of interactions with adolescent patients and consider screening either formally or informally for suicidal ideation. A recent study evaluated the feasibility of screening nonpsychiatric patients for suicide risk and targeted patients between the ages of 10 and 21 years. In this study interval, 37 of 50 patients with psychiatric complaints screened positive for suicide risk. However, 27 of 106 patients evaluated for nonpsychiatric complaints also screened positive for suicide risk. Each of the patients underwent formal psychiatric consultation, and none of the patients with nonpsychiatric complaints warranted hospitalization but were provided with available outpatient psychiatric services. Interestingly, screening of nonpsychiatric patients did not increase the overall length of stay.3

Was the patient found accidentally?

Did a low-risk gesture precede a phone call for help?

Is the patient sad to have survived?

Is the patient having increasing thoughts of suicide?

Does the patient have a plan? Has the patient gathered the means to act on that plan?

Is the patient feeling depressed or hopeless, or does the patient appear withdrawn?

What are the patient’s risk factors for future suicidal ideation or attempts?

A practice guideline of the American Psychiatric Association summarized large amounts of retrospective data regarding risk factors in patients who committed suicide.12 The relative importance and clinical utility of such risk factors can be challenging, however. Seemingly innocuous patient data may represent significant risk, as evidenced by studies demonstrating a higher suicide rate in women who received breast implants.13 Such epidemiologic studies are difficult to translate into clinical practice, but they do provide an understanding of the complexity of risk stratification in suicidal and homicidal patients.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Most Common and Most Threatening Presentations

Common manifestations of suicidality include minor threats or ideation of suicide by nonlethal means (Box 196.1). The most frequent ED scenarios involve young female patients who report a recent ingestion. Depressive symptoms are also common.

Men are far more likely to complete suicide.4 Threatening scenarios include attempts with potentially lethal consequences, a history of previous attempts, traumatic attempts that are difficult to recognize (e.g., single-car motor vehicle crashes), and elderly men with suicidal ideation.

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing in patients with threats of harm to self should focus on the mechanism of the suicidal attempt and any significant comorbid disease (including alcohol and drug abuse). Specific testing may help in evaluating certain treatable ingestions, such as acetaminophen or salicylates; in many cases, however, no specific testing is required. Imaging should be ordered appropriately for patients whose harmful actions involve jumping, hanging, or other traumatic injuries. Screening laboratory tests may be required to arrange for transfer or admission to a psychiatric facility, although such testing has little diagnostic value in the ED evaluation and treatment of suicidal or homicidal patients.14

Treatment

Contracts for safety are pacts that include a patient’s promise to seek immediate evaluation should thoughts of violence or self-harm increase. Current American Psychiatric Association guidelines do not recommend contracts for safety in emergency situations,12 although such understandings should be reinforced with any patient who is discharged after psychiatric evaluation in the ED.

Tips and Tricks

Establish referral patterns with consultants and mental health services in advance.

Know your local resources for inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care.

Do not be judgmental or condescending. Despite being in crisis, patients perceive your degree of concern or lack of compassion.

Do not allow staff to make pejorative comments in which they “instruct” patients how to complete a future suicide attempt.

Deescalate the situation by using calming mannerisms, voice, and tone.

Be safe—stay between the door and the patient.

Do not approach violent patients alone.

Ask permission to sit down beside the patient and have a conversation. Be willing to listen.

Involuntary commitment is frequently reportable on job applications and physician licensure. Voluntary commitment is seen as asking for help. This distinction can be used to persuade patients to agree to admission and to seek future help without long-term repercussions.

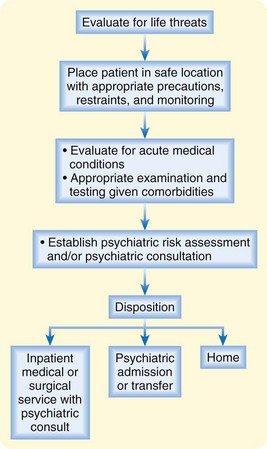

Disposition

Once the initial challenges of medical assessment have been met, the practitioner should determine the safest and most appropriate disposition for the individual patient’s social condition (Fig. 196.1). Psychiatric consultants often aid in the necessary evaluation, admission, or follow-up of at-risk patients. If the clinician has significant concerns, the patient should be admitted or transferred to an appropriately safe inpatient setting. Patients may need to be committed for involuntary psychiatric admission if they are not willing to sign in voluntarily.

One prospectively validated tool that is valuable for use in the ED is the Modified SAD PERSONS Scale developed by Hockberger and Rothstein in 1988 (Table 196.1). The scale uses a series of criteria that allow easy review of risk factors and assist in the identification of conditions that should prompt admission. Patients with a low score are less likely to have adverse events.15 However, patients testing positive for anxiety and hopelessness with concurrent depression are at increased risk to commit suicide.7

Table 196.1 Modified Sad Persons Scale of Hockberger and Rothstein: Based on the SAD PERSONS Mnemonic

| PARAMETER | FINDING | POINTS |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1 |

| Female | 0 | |

| Age | <19 yr | 1 |

| 19-45 yr | 0 | |

| >45 yr | 1 | |

| Depression or hopelessness | Present | 2 |

| Absent | 0 | |

| Previous attempts or psychiatric care | Previous suicide attempts or psychiatric care | 1 |

| Neither | 0 | |

| Excessive alcohol or drug use | Excessive | 1 |

| Not excessive or none | 0 | |

| Rational thinking loss | Lost as a result of an organic brain syndrome or psychosis | 2 |

| Intact | 0 | |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | Separated, divorced, or widowed | 1 |

| Married or always single | 0 | |

| Organized or serious attempt | Organized, well thought out, or serious | 2 |

| Neither | 0 | |

| No social support | None (no close family, friends, job, or active religious affiliation) | 1 |

| Present | 0 | |

| Stated future intent | Determined to repeat or ambivalent about the prospect | 2 |

| No intent | 0 | |

| SCORE* | MANAGEMENT | |

| 0-5 | May be safe to discharge, depending on circumstances | |

| 6-8 | Requires emergency psychiatric consultation | |

| 9-14 | Probably requires hospitalization | |

* The score equals the points for all 10 parameters: minimum score, 0; maximum score, 14. The higher the score, the greater the risk for suicide. A patient with a score of 5 or less rarely requires hospitalization.

Adapted from Hockberger RS, Rothstein RJ. Assessment of suicide potential by non-psychiatrists using the SAD PERSONS score. J Emerg Med 1988;6:99–107.

Are you here because you tried to hurt yourself?

In the past week, have you been having thoughts about hurting yourself?

Have you tried to hurt yourself in the past other than this time?

Has something very stressful happened to you in the past few weeks?3,16,17

Fights: During the last 12 months, have you been in a physical fight?

Hurt: During the last 12 months, have you been in a fight in which you were injured and had to be treated by a physician or nurse?

Threatened: During the last 12 months, have you been threatened with a weapon (knife or gun) on school property?

Smoker: Have you ever smoked cigarettes regularly (1 cigarette per day for 30 days)?6

A positive screen for suicidal or homicidal ideation or intent should prompt further evaluation and management, but patients may be discharged home if they are deemed safe after medical evaluation and psychiatric consultation (Box 196.2). Among patients discharged from the ED, significant predictors of return visits within 30 days include lack of a caregiver at the time of discharge and a history of a previous suicide attempt.18 A treatment plan, return precautions, and conditions for safety should be clear, well documented, and understood by all parties involved (including friends, family, and caregivers of the patient, especially when children or adolescents are involved).

Box 196.2

Reassuring Factors for Safe Discharge

Care established for mental, physical, and substance abuse disorders

Problem-solving and conflict resolution skills

Cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support the patient

From American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. November 2003. Available at http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/prac_guide.cfm.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Document the patient’s risk factors, psychiatric history, medical history, and discussions with supplemental historians (friends, family, police).

Record the process of admission or discharge and make note of risk stratification and medical decision making.

Carefully document the reasons for psychiatric committal, and give specific examples.

Document discussions and decision making with psychiatric consultants.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Patients who are going to be discharged must be sober.

Contract for safety: patients must state that they will not harm themselves and that they will return to the emergency department if thoughts of violence or self-harm return.

Patients must be discharged to a safe environment, such as home with supportive friends or family who are able to offer needed assistance.

It should be made clear that if patients’ conditions change, they should return to the emergency department for reevaluation. Patients should be made welcome to do so at any time.

Resources for outpatient follow-up should be appropriate to the social situation.

If possible, confirm that patients have a designated time and place for follow-up.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/prac_guide.cfm, November 2003. Available at

Cunningham R, Knox L, Fein J, et al. Before and after the trauma bay: the prevention of violent injury among youth. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:490–500.

Newton AS, Hamm MP, Bethell J, et al. Pediatric suicide-related presentations: a systematic review of mental health care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:649–659.

1 National Institute of Mental Health. NIH Publication No. 06-4594. Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-the-us-statistics-and-prevention/index.shtml

2 Newton AS, Hamm MP, Bethell J, et al. Pediatric suicide-related presentations: a systematic review of mental health care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:649–659.

3 Horowitz L, Ballard E, Teach SJ, et al. Feasibility of screening patients with nonpsychiatric complaints for suicide risk in a pediatric emergency department: a good time to talk? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:787–792.

4 Doshi A, Boudreaux E, Wang N, et al. National study of US emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury 1997-2001. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:369–375.

5 Hamm MP, Osmond M, Curran J, et al. A systematic review of crisis interventions used in the emergency department: recommendations for pediatric care and research. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:952–962.

6 Cunningham R, Knox L, Fein J, et al. Before and after the trauma bay: the prevention of violent injury among youth. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:490–500.

7 Diazgranados N, Ibrahim LA, Brutsche NE, et al. Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1605–1611.

8 Biros MH, Mann J, Hanson R, et al. Unsuspected or unacknowledged depressive symptoms in young adult emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:288–294.

9 Roy A, De Jong J, Linnoila M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid metabolites and suicidal behavior in depressed patients: a 5-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:609–612.

10 Coccaro EF, Siever LJ, Klar HM, et al. Serotonergic studies in patients with affective and personality disorders: correlates with suicidal and impulsive behaviors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:587–599.

11 Mann JJ, Malone KM. Cerebrospinal fluid amines and higher-lethality suicide attempts in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:162–171.

12 American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/prac_guide.cfm, November 2003. Available at

13 Villeneuve P, Holowaty E, Brisson J, et al. Mortality among Canadian women with cosmetic breast implants. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:334–341.

14 American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Available at http://acep.org/webportal/PracticeResources/ClinicalPolicies

15 Hockberger R, Rothstein R. Assessment of suicide potential by nonpsychiatrists using the SAD PERSONS score. J Emerg Med. 1988;6:99–107.

16 Horowitz LM, Wang PS, Koocher GP, et al. Detecting suicide risk in a pediatric emergency department: development of a brief screening tool. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1133–1137.

17 King CA, O’Mara RM, Hayward CN, et al. Adolescent suicide risk screening in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1234–1241.

18 Groke S, Zink A, Bennett A, et al. Factors predicting return visits among emergency department patients with psychiatric complaints. Ann Emergy Med. 54(3), 2009.