chapter 8

Seizures and Epilepsy

This chapter is a brief discussion of the clinical aspects of epilepsy. It does not discuss pathophysiology. The numerous classification schemes [1–4] also are not discussed as it is inevitable that with advancing knowledge these will continue to evolve.

The basic principles of clinical assessment and management of patients suffering from a suspected seizure or epilepsy (recurrent seizures) will be discussed. A comprehensive discussion of epilepsy can be found in numerous textbooks [5–7]. Treatment is documented in Appendix C but, as it will continue to evolve rapidly, any discussion in a textbook will quickly be out of date. Therefore, links to neurology- and epilepsy-related websites are included in Chapter 15, ‘Further reading, keeping up-to-date and retrieving information’. It is anticipated that these websites will provide the reader with the up-to-date information that a textbook cannot provide.

CLINICAL FEATURES CHARACTERISTIC OF EPILEPSY

Epilepsy (apart from the very rare reflex epilepsies discussed below) is:

Epilepsy is an episodic disturbance of function that occurs with variable frequency from a single seizure in a lifetime to many seizures per day. Apart from reflex epilepsy (see ‘Reflex epilepsies’ below), when seizures will occur is unpredictable and can be any time of the day or night and under any circumstances. Some patients may experience a brief warning (aura), lasting seconds only, leading up to the ictus. Unless a patient has more than one type of seizure each episode is identical or almost identical (stereotyped), in terms of the clinical manifestations, to the previous one. If a patient suffers from multiple types of seizures each will be have their own stereotypical features. Seizures are brief, usually lasting less than 1–3 minutes (even tonic–clonic seizures) and rarely 5–10 minutes [8]. There are characteristic positive phenomena, i.e. abnormal movements or smell, taste, sensory, psychic or visual sensations. A loss of function, such as paralysis or sensory loss, is NOT a feature during a seizure but may follow a seizure; this is referred to as Todd’s palsy (see ‘Tonic–clonic seizures’ below).

THE PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH A SUSPECTED SEIZURE OR EPILEPSY

1. Confirm that the patient has suffered a seizure.

2. Characterise the type(s) of seizure(s).

3. Assess the frequency of seizures.

4. Identify any precipitating causes.

6. Decide whether to treat or not.

7. Choose the appropriate drug and dose and monitor the response to therapy.

8. Advise regarding lifestyle.

9. Consider surgery in patients who fail to respond to drug therapy.

10. Decide whether and when to withdraw therapy in ‘seizure-free’ patients.

CONFIRMING THAT THE PATIENT HAS HAD A SEIZURE OR SUFFERS FROM EPILEPSY

In patients with suspected seizure(s) the best history-taking technique is to obtain a blow-by-blow description of the episode or several of the episodes. Concentrate on the periods immediately before, during and after the event or ictus. These are referred to as the pre-ictal, ictal and post-ictal periods. The correct diagnosis depends on establishing the exact duration and nature of the symptoms that occur during each of these three phases. The alternative diagnoses that may be confused with epilepsy have been discussed in Chapter 7, ‘Episodic disturbances of neurological function’.

Useful questions to ask the patient

• What were you doing just before the episode? The circumstances under which the episode occurred may provide a vital clue in terms of aetiology or precipitating factors: flashing lights in a discotheque with photosensitive epilepsy or a seizure during venesection suggesting a seizure probably secondary to syncope.

• Was there any warning? If so, what was the exact nature of this warning and how long did it last? A brief warning or aura lasting only seconds is very typical of epilepsy; a more prolonged warning would point to a possible alternative diagnosis.

• What was your next recollection? Can you establish how long this was after the episode commenced? A short period of lost time, 10 minutes or at most 20 minutes, is more in keeping with epilepsy.

• When you came to were you aware of anything the matter? A period of post-ictal drowsiness or confusion in the absence of a head injury strongly suggests epilepsy.

• Did you injure yourself? This is non-specific, but a dislocated shoulder occasionally occurs with tonic–clonic seizures and an injury indicates a fall, thus reducing the number of diagnostic possibilities.

• During the episode did you bite your tongue or cheek or lose control of your bladder or bowels? These occur with tonic–clonic seizures.

• Have you ever had any unexplained motor vehicle accidents? An explanation may be a seizure without warning.

• When you are watching a television program that you are interested in or having a conversation with a person, do you ever miss parts of the program or conversation? An affirmative answer to this suggests the possibility of minor absence or complex–partial seizures that the patient may not have noticed. However, when patients are just sitting in front of the television it would be not uncommon through lack of concentration to miss parts of the program. On the other hand, if it interrupts a program that the patient is particularly interested in, it is more likely to be a minor seizure.

• Do people accuse you of being a daydreamer? It is not uncommon for children and adolescents to be thought of as daydreamers when they have been having unrecognised minor seizures. It is also not uncommon for children and teenagers to actually daydream, so interpret the answer to this question with caution. If the patient has suffered from repeated episodes, establish if each and every episode was identical or whether there may have been different types of seizures so that detailed questioning of several different events is necessary.

• Have you ever been able to prevent one of these episodes and, if so, how? Seizures secondary to syncope or hypotension may be prevented if the patient assumes a recumbent posture immediately after they experience the first warning.

Useful questions to ask an eyewitness or relative

Some patients can suffer unrecognised seizures for many years [9], particularly children and teenagers who are often thought to be daydreaming. Relatives may have witnessed a number of episodes and not recognised them as seizures.A useful sequence of questions includes:

1. Have you ever seen the patient suddenly interrupt what they were doing and stare into space, where their eyes were open but they did not respond to you? If the answer is yes, this is in keeping with absence or complex–partial seizures.

2. What was the patient doing at the time the episode commenced?

3. What was the first thing that you noticed and how long did it last?

4. What was the next thing that you noticed and how long did it last?

5. What was the next thing that you noticed and how long did it last?

• During the episode was the patient able to hear what you were saying or were they out to it? If the answer is no, this indicates a loss of awareness suggesting a generalised seizure or complex–partial seizure.

• Did you see any excessive blinking or abnormal chewing movements of the mouth? These occur with absence and complex–partial seizures, respectively.

Epilepsy in the elderly

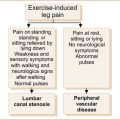

It is a common misconception that epilepsy is a disease of childhood. While this is largely true of absence (petit-mal) seizures, which are very rare in adults and often present when they do occur with absence status epilepsy, seizures do occur in the elderly and the incidence increases with increasing age, as shown in Figure 8.1. Elderly patients with epilepsy most often present with tonic–clonic or complex–partial seizures that have a higher recurrence rate than in the younger population. The complex–partial seizures are often difficult to diagnose since they present with atypical symptoms, particularly prolonged post-ictal symptoms including memory lapses, confusion, altered mental status and inattention [10].

FIGURE 8.1 Schematic diagram to show that both maturational factors in seizure susceptibility derived from onset of age-related epileptic disorders and febrile convulsions (a) and environmental factors derived from age-related risk of cerebral injury (b) combined to yield the incidence of epilepsy by age (c) Reproduced from ‘Seizures and Epilepsy’, by J Engel, Jr. In: Contemporary Neurology Series, edited by F Plum, Vol 31, 1989, FA Davis Company, Figure 5.3, p 115 [12]

Although there is a continuing incidence of seizures throughout life, they are more common in the first 5 years. There is also a higher incidence in the 70- to 80-year-old age group [11].

CHARACTERISATION OF THE TYPE OF SEIZURE

The clinical manifestations of the more common types of seizures is discussed here; more detail can be found in textbooks [12–14]. The commonest seizures in clinical practice are:

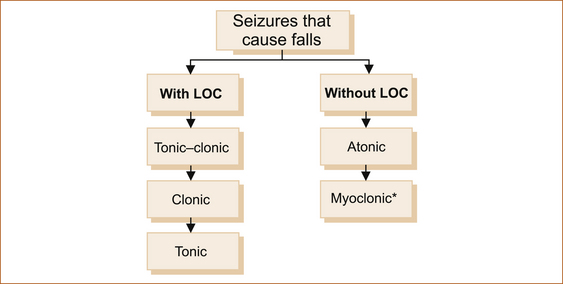

1. seizures that cause the patient to fall with or without loss of consciousness (see Figure 8.2)

2. seizures that are not associated with a fall with or without loss of consciousness (awareness; see Figure 8.3).

Tonic–clonic seizures

• Immediately before ictus: The aura or warning if it occurs may indicate a focal onset such as déjà vu, jamais vu or unpleasant olfactory (smell) or gustatory (taste) phenomena that are suggestive of a temporal lobe origin. The aura may consist of a non-specific epigastric rising sensation, where an unpleasant feeling commences in the epigastrium and rises up towards the head very quickly over a few seconds, a non-specific light-headedness or an odd feeling in the head. Tonic–clonic seizures preceded by an aura are often referred to as focal seizures with secondary generalisation, as opposed to primary generalised epilepsy where the tonic–clonic seizure is not of focal origin. The essential feature is that the aura is identical each time and more importantly is very brief, usually lasting seconds only.

• During ictus: With or without warning (an aura) the patient will fall to the ground, rigid, with the teeth clenched, arms and legs extended and eyes open. At times the arms may be flexed instead of extended. Many eyewitnesses describe the eyes as rolling up into the top of the head, which means that the eyes are open. This tonic phase is brief, usually less than 30 seconds, and it is followed by repetitive jerking (clonic phase) of the arms and legs, which is also brief, usually less than 1 or 2 minutes, although it may be prolonged up to 10 minutes. Seizures may last longer if the patient develops status recurrent seizures without recovery of consciousness between seizures, referred to as status epilepsy. During a tonic–clonic seizure the patient may bite the tongue or cheek, froth at the mouth or be incontinent of urine and/or faeces. If urinary or faecal incontinence occurs, it is during the tonic phase.

• After ictus: Immediately following the seizure the patient is limp, drowsy and confused. This period of post-ictal confusion and drowsiness varies depending upon the duration of the seizure and the age of the patient. If seizures are brief the duration may be less than a few minutes; with more prolonged seizures, the period of confusion can last much longer, usually less than half an hour. In the elderly it may last for several days in the absence of any obvious metabolic or infective process to account for such confusion. Very rarely, paralysis of a limb(s) follows a seizure, an entity called Todd’s palsy. Again, this tends to be more prolonged in the elderly.

Atonic seizures

Drop attacks due to epilepsy mainly occur in childhood; drop attacks that occur in elderly adults are thought not to be epileptic in origin and are discussed in Chapter 7, ‘Episodic disturbances of function’. The Lennox–Gastaut syndrome is seen in childhood and consists of multiple seizure types including atypical absence seizures, myoclonic, tonic–clonic and atonic seizures with often a degree of intellectual disability [5].

Myoclonic seizures

In patients with myoclonic epilepsy, these myoclonic jerks are more frequent, often occur during sleep but characteristically occur first thing in the morning on awakening. They affect the whole body or a single limb and may be single or repetitive jerks. In myoclonic seizures the patient is fully aware of what is happening. There is no aura, loss of awareness or post-ictal confusion, i.e. the patient is normal immediately before and after the event. Myoclonus induced by movement is a feature of post-hypoxic myoclonus [15].

Complex–partial seizures

• Immediately before ictus: The duration of the aura is usually measured in seconds; the symptoms of aura have been described above.

• During ictus: The ictus usually lasts seconds to a few minutes. The patient is not aware of what is happening, nor are they able to respond to any verbal or painful stimuli. In the words of two relatives witnessing minor seizures: ‘the lights were on but no one was at home’ or ‘there were no sheep in the top paddock’. There may be involuntary movements of the mouth or limbs, depending on which area of the brain is the focus for the seizure.

• After ictus: There is a period of post-ictal confusion lasting several minutes during which the patient can usually respond to outside stimuli but is clearly disoriented and confused [18]. The patient is unable to relate what happened during the event.

Absence (petit-mal) seizures

Absence epilepsy generally occurs in childhood and is very rare as a primary presentation in adults. In retrospect, however, when one takes a careful history from a patient with their first tonic–clonic seizure, many patients have had unrecognised absence seizures [9] in childhood and have simply been regarded as either dull or a daydreamer.

• Immediately before ictus: The absence seizure is characterised by no warning unless it is an atypical absence.

• During ictus: The period of impaired consciousness is brief. In one study the average seizure duration was 9.4 seconds (range 1–44 seconds, SD 7 seconds), 26% of seizures were shorter than 4 seconds and 8% were longer than 20 seconds [19]. The patient simply stares into space and may blink, but they are clearly unresponsive to either verbal or painful stimuli. They have no recollection of what happened or was said to them during the episode.

• After ictus: Immediately following the ictus, the patient is able to resume a conversation and the activity that they were undertaking without any post-ictal confusion.

It is surprising how many absence seizures patients can experience without people actually noticing them because they are so brief. Absence seizures can readily be induced by hyperventilation (HV). In one study of 47 children with childhood absence seizures, HV induced seizures in 83% (39/47) of children. Of the eight children who did not have seizures induced by HV, four were too young to perform HV. In the other four children, HV was performed but may not have been performed well [19].

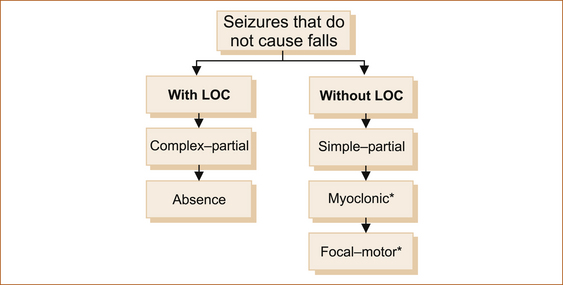

The EEG in absence seizures shows a characteristic 3 per second spike and wave (see Figure 8.4).

Simple partial seizures

The essential characteristic of simple partial seizures is that they can occur at any age in either sex and consist of a brief stereotyped sensation without loss of awareness, i.e. the patient is fully conscious of what is happening and is able to describe the whole episode from start to finish. There is no warning or aura, nor is there any post-ictal drowsiness or confusion. Examples of this type of epilepsy are patients who experience a tingling sensation that may commence in their feet and rise up to the top of the head and sometimes go back down again to their feet, over a matter of seconds.

Benign focal seizure of childhood

There are a number of benign focal seizures of childhood [20, 21]. There are currently three identifiable electroclinical syndromes recognised by the International League against Epilepsy (ILAE) [22]: rolandic epilepsy, Panayiotopoulos syndrome (PS) or common autonomic epilepsy and the idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut (ICOE-G). They produce terrifying manifestations. Details are given in Appendix B, ‘Benign focal seizures of childhood’, because they are rare and atypical with the duration of symptoms being longer than for most other seizure types.

Febrile convulsions

Febrile convulsions affect 2% to 5% of all children and usually appear between 3 months and 5 years of age. Febrile convulsions may be provoked by any febrile bacterial or viral illness and no specific level of fever is required to diagnose febrile seizures. It is essential to exclude underlying meningitis either clinically or, if any doubt remains, by lumbar puncture. The risk of epilepsy following a febrile seizure is 1% to 6% [23].

Reflex epilepsies

The reflex epilepsies are syndromes in which all epileptic seizures are precipitated by sensory stimuli. Generalised reflex seizures are precipitated by visual light stimulation, thinking and decision making. Numerous triggers can induce focal reflex seizures, including reading, writing, other language functions, startle, somatosensory stimulation, proprioception, auditory stimuli, immersion in hot water, eating and vestibular stimulation [24].

Consider possible multiple types of seizures

Having established that the patient has suffered a seizure, the next step is to determine whether they suffer from any other seizure types and whether they have suffered from undiagnosed seizures in the past. Although most patients who present with their first tonic–clonic seizure have not had other manifestations of epilepsy, with detailed questioning it is not uncommon for patients to have had unrecognised myoclonic seizures and/or minor absence or complex–partial seizures in the past [9].

Pseudoseizures

Pseudoseizures are paroxysmal changes in behaviour that resemble epileptic seizures, but which are without organic cause and the expected EEG changes. Longer ictal duration and less stereotypy (variation of the manifestations from one episode to the next) are characteristic. Other characteristic features include asynchronous extremity movements, atypical vocalisation, alternating head movements, talking or screaming, opisthotonic posturing (arching of the back) and pelvic thrusting [25].

An increasing frequency of ‘seizures’ with escalating doses of anticonvulsants should alert the clinician to the possible diagnosis [26]. The diagnosis can be very difficult as up to 30% of patients with pseudoseizures have epileptic seizures as well and pelvic thrusting can be a very rare manifestation of temporal lobe or frontal lobe epilepsy [27]. The diagnosis of psychogenic pseudoseizures has improved with the availability of video-EEG monitoring [28]. If pseudoseizures are suspected, one way to confirm the diagnosis is to instruct family members, nursing staff on the ward or anyone who may witness an episode to try and interrupt what is happening either by talking to the patient or by employing a painful stimulus, e.g. pinching the skin over the medial aspect of the elbow. Organic seizures, as opposed to pseudoseizures, cannot be interrupted.

ASSESSING THE FREQUENCY OF SEIZURES

The patient with their ‘first seizure’

As already stated it is not uncommon to see patients with their first apparent tonic–clonic seizure who have had a previous seizure or a long history of unrecognised minor seizures or myoclonus [9]. Ask the patient whether they have frequent involuntary brief jerking of one limb or all of the body, similar to the sensation that they experience when they are just falling asleep. These involuntary jerks (termed myoclonus) can occur infrequently, perhaps a few times per year in normal individuals, whereas in patients with epilepsy they occur more frequently and often first thing in the morning upon wakening, particularly in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy syndrome. Although the patient is very aware of these myoclonic jerks, they interfere so little with their life that often they do not seek medical attention. Similarly, minor seizures may go undetected or undiagnosed for many, many years. Often detailed questioning of relatives or friends using the questions described above will elicit a prior history of previously unrecognised minor seizures. Ascertain how frequently the various types of seizures occur (i.e. many times per day, daily, weekly etc).

Status epilepsy

CONVULSIVE STATUS EPILEPSY

Status tonic–clonic (convulsive) epilepsy consists of continuous or rapidly repeating seizures and is a medical emergency. The treating doctor should not leave the bedside until seizures cease. There are published guidelines for the management of status epilepsy [29–31]. Guidelines are often updated and every institution should have access to them. Patients who do not respond to initial therapy should be treated in an intensive care unit, as artificial ventilation and haemodynamic support are required.

NON-CONVULSIVE STATUS EPILEPSY

Non-convulsive status epilepsy is an epileptic state in which there is some impairment of consciousness associated with ongoing seizure activity on the EEG [32]. It is often a sequel to convulsive status epilepsy [32]. Patients may present in a coma without any overt signs of seizure activity [33].

IDENTIFYING ANY PRECIPITATING CAUSES

Identifying a reversible precipitating cause is important as avoidance in the future can reduce the risk of subsequent seizures. Most seizures are due to an abnormal electrical discharge within the brain, often referred to as primary epilepsy. Seizures can also be secondary to the hypotension that occurs for example with syncope, a Stokes–Adams attack, alcohol abuse or withdrawal of sedative or hypnotic drugs.

• In patients with primary epilepsy, sleep deprivation, photic stimulation, alcohol abuse [34], menstruation and an intercurrent infective illness may potentially predispose to recurrence [35].

• Vomiting and/or diarrhoea alter drug levels, predisposing to recurrent seizures, and many drugs, including psychotropics, local and general anaesthetics, narcotics, antiarrhythmics and antibiotics, are recognised precipitating factors for seizures [36].

• Poor compliance is one, if not the commonest, cause of recurrent seizures in patients on anticonvulsants [34].

ESTABLISHING AN AETIOLOGY

Most patients with epilepsy do not have any identifiable underlying pathology. It is possible that with future advancements in the understanding of epilepsy more causes will be identified. Focal-motor seizures, complex–partial seizures and, particularly, seizures associated with a focal neurological deficit are more likely to have identifiable pathology on imaging [37].

Seizures may occur with alcohol or drug withdrawal, infective processes within the central nervous system, drugs, benign and malignant tumours, just to mention a few possible aetiologies. Seizures can be the presenting symptom of disturbances of cardiac rhythm [38] or, rarely, secondary to severe pain, for example in patients with trigeminal neuralgia [39]. Detailed lists can be found in textbooks on epilepsy [5–7, 14, 40, 41]. This means that it is not possible to be dogmatic about what investigation(s) should be performed in an individual patient; suffice to say that every effort should be made to find a cause.

Investigations

• Some would argue that it is justifiable to perform medical imaging of all adult patients who present with tonic–clonic, complex–partial and focal motor seizures [42, 43]. Others would argue that there is currently insufficient data to support or refute recommending any of these tests for the routine evaluation of adults presenting with an apparent first unprovoked seizure [43]. The yield of currently available imaging techniques is about 10%. Current recommendations advocate an EEG, CT or MRI brain scan in all patients presenting with a first unprovoked seizure [43]. In reality most, if not all, patients will demand imaging for reassurance that they do not have a brain tumour.

• Laboratory tests, such as blood counts, blood glucose and electrolytes, particularly sodium, lumbar puncture and toxicology screening may be helpful as determined by the specific clinical circumstances based on the history, physical and neurological examination, but there are insufficient data to support or refute recommending any of these tests for the routine evaluation of adults presenting with an apparent first unprovoked seizure [43].

• On the other hand, although metabolic disturbances causing seizures are rare they are readily correctable, particularly hypoglycaemia. When a patient presents with a seizure, probably the single most important test to perform immediately is a serum glucose to exclude hypoglycaemia. Other metabolic disturbances, such as hyponatraemia, hypocalcaemia and an elevated urea, may cause seizures and, as a general principle, these investigations are without risk and the subsequent management is easy. It would seem reasonable to exclude metabolic causes in all patients.

DECIDING WHETHER TO TREAT OR NOT

In many patients with simple partial seizures, reassurance that nothing sinister is the matter suffices and they do not wish to take medication to stop such trivial symptoms. In patients with an isolated idiopathic (no particular cause) tonic–clonic seizure the subsequent risk of further seizures varies from study to study. In one study of children it was 54% [44], while in another study of adults there was a 27% risk of recurrence at 36 months [45]. A first seizure provoked by an acute brain disturbance is unlikely to recur (3–10%), whereas a first unprovoked seizure has a recurrence risk of 30–50% over the next 2 years [46].

The number of seizures of all types at presentation, the presence of a neurological disorder and an abnormal EEG are significant risk factors for recurrent seizures. An abnormal EEG is defined as specific focal or generalised epileptiform or slow wave abnormalities. Individuals with two or three seizures plus a neurological disorder and/or an abnormal EEG have been identified as a high-risk group with a 73% incidence of recurrent seizures at 5 years [47]. In the same study the recurrence rate at 5 years in patients with a single seizure, a normal EEG and no neurological abnormality was 39% [47].

In a study of immediate versus delayed treatment with currently available anticonvulsants, immediate treatment did not reduce the long-term recurrence rate. At 5-year follow-up, 76% of patients in the immediate treatment group and 77% of those in the deferred treatment group were seizure free (difference –0.2%, 95% CI –5.8% to 5.5%) [48]. When confronted with such a low risk of recurrence many patients elect not to take antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment after a first seizure [46]. It would therefore seem reasonable not to recommend therapy in patients with an isolated tonic–clonic seizure in the absence of a positive family history, an abnormal EEG and pre-existing cerebral pathology, particularly if there was an easily reversible precipitating cause such as sleep deprivation. The patient in this situation often decides. The question to put to the patient is: ‘What effect would another seizure have on your life?’ The commonest reason patients give for wanting to go onto medication is that a further seizure would terrify them, although more often it is the unacceptable social implications and the effect on their ability to drive, and thus on their employment, that influences their decision whether to take medication or not. Being employed is a major reason why patients continue to drive against medical advice [49].

CHOOSING THE APPROPRIATE DRUG, DOSE AND ONGOING MONITORING OF THE RESPONSE TO THERAPY

Treatment is targeted primarily to:

• assist the patient in adjusting psychologically to the diagnosis and in maintaining as normal a lifestyle as possible

• reduce or eliminate seizure occurrence

• avoid or minimise the side effects of long-term drug treatment.

Most patients with more than one seizure require prophylactic AED therapy. Some seizure types or epilepsy syndromes may respond to certain drugs while other drugs may exacerbate the seizures [50, 51].

Side effects are a significant reason for discontinuing an AED, particularly in the elderly [52].

When monotherapy does not control seizures, review the diagnosis of epilepsy and check for compliance with medication. Failure of the first AED due to lack of efficacy (and not due to incorrect choice of drug, wrong dose, incorrect dosing schedule or poor compliance) implies refractoriness and trying multiple AEDs one after another is unlikely to be successful [53]. Combination therapy should be considered when treatment with two first-line AEDs has failed or when the first well-tolerated drug substantially improves seizure control but fails to produce freedom from seizure at maximal dosage. In this instance, an AED with different and perhaps multiple mechanisms of action should be added. Strategies for combining drugs should involve individual assessment of the patient’s seizure type, together with an understanding of the pharmacology, side effects and interaction profiles of the AEDs [54]. The choice of drugs to use in combination should be limited to two or at most three AEDs.

Current treatment recommendations and the potential side effects of specific drugs are given in Appendix C, ‘Currently recommended drugs for epilepsy’, and links to websites that should provide more up-to-date information are given in Chapter 15, ‘Further reading, keeping up-to-date and retrieving information’.

Choosing the dose

Other than with status epilepsy, there is no need to reach a therapeutic dose rapidly. Therefore, treatment should commence with the lowest possible dose and increase very slowly over weeks as this may reduce the incidence of side effects [55, 56]. The number of doses per day is dependent on the half-life of the drug, but medications prescribed more than twice a day are associated with an increasing incidence of poor compliance [57].

Monitoring the response

In many patients complete freedom from seizures is not possible and sensible decisions regarding the efficacy of medication can be made only with careful assessment of seizure frequency. Seizure frequency has a significant impact on quality of life [58]. Although it is recommended that patients keep a diary to record the frequency of their seizures, very few do. It is important for the treating doctor to keep detailed notes on behalf of the patient and refer to these notes when deciding if a particular AED has been effective in reducing the number of seizures. Monitoring the response to treatment at times can be extraordinarily difficult, particularly in young patients who through embarrassment will often deny forgetting their medication, drinking too much alcohol or staying out all night.

Intractable epilepsy

Measuring serum levels

Serum AED measurements are useful when the level directly reflects efficacy; this is not the case for all drugs. Other clinical situations where AED monitoring is useful include checking for compliance or toxicity, as a guide to adjusting the dose when another drug is added or during pregnancy [59].

ADVICE REGARDING LIFESTYLE

Each country has different regulations with regard to driving and epilepsy, and it is important for all clinicians who care for patients with epilepsy to have a copy of their respective country’s (or state’s) guidelines. In recent years restrictions have been less stringent, reflecting the low contribution of seizures to the overall road toll [60]. In some countries the restriction on driving is very severe, whereas in others a more lenient approach is taken.

Essentially, a sufficient period of time needs to elapse to be certain that a recurrent seizure is unlikely to occur. In one study patients who had seizure-free intervals of 12 months or longer had 93% reduced odds of motor vehicle accidents compared to patients with shorter seizure-free intervals. The majority (54%) of patients who crashed were driving illegally, with seizure-free intervals shorter than legally permitted [61], and 20% had missed an AED dose just prior to the crash. Patients should be informed that, although the risk of a seizure is small, the potential consequences could be disastrous. It is also a useful tactic to show patients the guidelines, explaining that the medical practitioner does not make the rules and that these rules are not there to punish patients with epilepsy but to protect the patient from hurting themselves or innocent people.

The risk of a seizure occurring while driving is also a reflection of the time spent driving. If the patient drives for only half an hour per day the risk of a seizure while driving is much lower than if they drive for 12 hours per day. For this reason in many countries the requirements are more stringent for commercial and heavy goods vehicle licenses than for private motor vehicle licenses [62].

Pregnancy and epilepsy

Although the increased risk of major congenital malformations in patients with epilepsy taking AED(s) during pregnancy is possibly 2–3 times that of the normal population [63], most pregnancies will result in a normal child. There is some debate about the exact role of AED exposure in pregnancy and any increased risk [64]. Some AEDs and the use of multiple AEDs (polypharmacy) may be associated with a greater risk [65–67]. Long-term cognitive problems in the child may also occur [65].

In clinical practice many patients attend their doctor to discuss withdrawal of medication when they are 2–3 months pregnant. Any teratogenic effects will have already occurred, and it is probably unwise and essentially too late to withdraw medication at this stage of the pregnancy. The risk of uncontrolled seizures during pregnancy needs to be weighed against the risk of AED exposure. An increased risk to the mother and infant is often quoted but it is difficult to find good evidence to justify this statement. In the European Registry of Antiepileptic Drugs and Pregnancy (EURAP) study, of 1956 pregnancies 58.3% were seizure-free throughout pregnancy. Seizures occurred during delivery in 60 pregnancies (3.5%), more commonly in women with seizures during pregnancy (odds ratio (OR): 4.8; 2.3–10.0). There were 36 cases of status epilepsy (12 convulsive), which resulted in stillbirth in only 1 case, but no cases of miscarriage or maternal mortality [68]. A Cochrane review has concluded that, based on the best current available evidence, it would seem advisable for women to continue medication during pregnancy using monotherapy at the lowest dose required to achieve seizure control [65].

Some patients seek advice about ceasing their AEDs prior to pregnancy and here the decision is more difficult. Even if the epilepsy is easily controlled, the patient has to be willing to run the risk of a recurrent seizure and the subsequent consequences regarding the alteration in their lifestyle, in particular driving. In general, if the epilepsy has been difficult to control, an argument can be made for the patient to remain on medication throughout the pregnancy. Accumulating evidence from drug registries suggests that the lowest possible dose and avoidance of certain drugs may be appropriate [68–70]. Patients willing to consider a mid-trimester termination can have testing for major malformations.

Some patients may experience an increased seizure frequency while others have fewer seizures [68]. Occasionally, patients not known to suffer from epilepsy have a tonic–clonic seizure during labour and, although other serious disorders need to be considered, often a detailed history will elicit a long history of infrequent minor and previously unrecognised seizures.1 Most patients with epilepsy will maintain control during pregnancy [68].

Potentially hazardous activities

Patients should be warned that it may be dangerous to go swimming or fishing, have a bath or walk near water if they are alone as a seizure could result in drowning [71]. Patients should also be advised not to scale heights, walk near the edge of cliffs, sky dive or scuba dive.

CONSIDERATION OF SURGERY IN PATIENTS WHO FAIL TO RESPOND TO DRUG THERAPY

Approximately one-third of patients with epilepsy are refractory to AED therapy and many of these patients are candidates for surgical treatment [72]. Among patients who do not respond to the first drug, the percentage who subsequently become seizure-free with additional AEDs is smaller (11%) [53]. Patients with refractory epilepsy should be referred to an appropriate centre earlier rather than later for potential surgery.

Investigation and treatment

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been pivotal in the evaluation of patients with partial seizures [73]. Patients with MRI-negative partial epilepsy may be candidates for additional neuroimaging techniques including positron emission tomography, MR spectroscopy and single photon emission tomography. Peri-ictal imaging may allow identification of the epileptogenic zone in patients with normal MRI scans.

In patients with refractory epilepsy, vagal nerve [74], hippocampal [75] and bilateral cerebellar [76] electrical stimulation have been advocated. These techniques have resulted in a modest reduction in seizure frequency but none has eliminated seizures altogether. On the other hand surgery, in particular temporal lobectomy for mesial temporal sclerosis, has been shown to be highly effective in a randomised controlled trial, with more than 50% of patients seizure-free as opposed to 8% in the non-surgical group [77].

Macroscopic and radiological evidence of total lesional excision with isolated structural lesions such as dysembryoplastic tumours, low-grade astrocytomas or focal vascular abnormalities is associated with excellent seizure-free outcome [78].

Corpus callosotomy is recommended for patients with atonic seizures or drop attacks [79, 80].

Hemispherectomy is now a widely accepted procedure for medically refractory, catastrophic hemispheric epilepsy. The classic anatomical hemispherectomy procedure has been abandoned in favour of functional or modified hemispherectomy [81].

WHETHER AND WHEN TO WITHDRAW THERAPY IN ‘SEIZURE-FREE’ PATIENTS

In other forms of epilepsy where remission can occur and a trial off AEDs is not unreasonable, the initial question to the patient must be: ‘What effect would a recurrent seizure have on your life?’ For example, the patient would be unable to drive for a prescribed period after the seizure and this could impact on their life and work. A recurrent seizure may occur in a situation where it would cause significant embarrassment or, worse still, possible injury. A minimum of 2 years free of seizures is recommended before considering withdrawal of medication [82]. Even when the risk of recurrence is low, it must be stated that there is no guarantee that there will not be a recurrent seizure. Recurrent seizures may occur after as many as 8 years off medication.2

In a review of 28 studies accounting for 4571 patients (2758 children, 1020 adults and a combined group of 793), most with at least 2 years of seizure remission, the proportion of patients with relapses during or after AED withdrawal ranged from 12% to 66% [83].

A higher-than-average risk of seizure relapse included:

• the presence of an underlying neurological condition

• abnormal EEG findings at the time of AED withdrawal in children [83].

Most relapses occur during or within the first 6 months after withdrawal [84]. At the time of writing there was no evidence to determine the rate of withdrawal [85], but it seems reasonable to reduce the dose slowly over several weeks to months.

COMMON TREATMENT ERRORS

In 1999 Feely [86] elegantly summarised many common treatment errors and most of his observations apply today. They include:

1. Incorrect or incomplete identification of seizure type(s), resulting in inappropriate choice of treatment: for example confusion between brief complex–partial seizures and absences or failure to recognise juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.

2. A drug appropriate for the patient’s seizure type(s) is chosen, but it is not appropriate for that patient: for example, phenytoin for an adolescent female (coarsening of facial features), valproic acid for a woman likely to become pregnant (increased risk of congenital malformations) or carbamazepine for a woman on the oral contraceptive pill (reduced contraceptive efficacy).

3. The diagnosis and choice of drug are correct, but the patient is given too low a dose (for example, only the ‘starting’ dose is tried) or the patient is given too high a dose too quickly.

4. The epilepsy is controlled, but the patient has problems with side effects and no change in the treatment (drug or dosage) is made.

5. The patient is seen by a specialist and referred back to the general practitioner with an appropriate recommendation regarding treatment, but when this proves ineffective further advice is not sought.

6. This author would add that, although a detailed explanation regarding treatment, lifestyle etc is provided at the time of the consultation, this information is often forgotten. It is for this reason that this author provides a copy of his letter to the referring doctor to all patients.

THE ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAM

No chapter on epilepsy would be complete without a discussion of the electro-encephalogram (EEG).

• A single inter-ictal (between seizures) EEG has a sensitivity of approximately 50% [87, 88] and a specificity of 97–98% [89, 90]. The sensitivity can be increased to 92% if a further three EEGs are performed [88].

• Sleep deprivation increases the number of abnormal EEGs [9, 91].

• Epileptiform abnormalities are more likely to be detected if the EEG is performed within the first 24 hours after a seizure [9].

• In adults the EEG is more likely to be abnormal in patients with generalised seizures than partial seizures [9].

• Prolonged monitoring with or without video monitoring is useful for patients with refractory epilepsy [92] or frequent seizures, particularly in childhood [93].

• Video-EEG monitoring is useful for patients with suspected pseudoseizures [94].

• EEG abnormalities have been found in 3.5% of 3726 children without epilepsy [90].

REFERENCES

1. Fisher, R.S., et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: Definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46(4):470–472.

2. Engel, J., Jr., A proposed diagnostic scheme for people with epileptic seizures and with epilepsy: Report of the ILAE task force on classification and terminology, 2006. Available: http://www.ilae-epilepsy.org/Visitors/Centre/ctf/overview.cfm (14 Dec 2009).

3. Engel, J., Jr. Classifications of the International League Against Epilepsy: Time for reappraisal. Epilepsia. 1998;39(9):1014–1017.

4. Everitt, A.D., Sander, J.W. Classification of the epilepsies: Time for a change? A critical review of the International Classification of the Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes (ICEES) and its usefulness in clinical practice and epidemiological studies of epilepsy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42(1):1–10.

5. Engel, J., Jr. Seizures and epilepsy. In: Plum F., ed. Contemporary neurology series, vol 31. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company; 1989:165. [203–207].

6. Shorvon, S.D. Handbook of epilepsy treatment: Forms, causes and therapy in children and adults. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. [304].

7. Engel J., Pedley T.A., eds. Epilepsy: A comprehensive textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2007:3056.

8. Jenssen, S., Gracely, E.J., Sperling, M.R. How long do most seizures last? A systematic comparison of seizures recorded in the epilepsy monitoring unit. Epilepsia. 2006;47(9):1499–1503.

9. King, M.A., et al. Epileptology of the first-seizure presentation: A clinical, electroencephalographic, and magnetic resonance imaging study of 300 consecutive patients. Lancet. 1998;352(9133):1007–1011.

10. Jetter, G.M., Cavazos, J.E. Epilepsy in the elderly. Semin Neurol. 2008;28(3):336–341.

11. Anderson, V.E. Family studies of epilepsy. In: Anderson V.E., et al, eds. Genetic basis of the epilepsies. New York: Raven; 1982:103–112.

12. Engel, J., Jr. Seizures and epilepsy. In: Plum F., ed. Contemporary neurology series, vol. 31. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company; 1989:536.

13. Lüders, H. Textbook of Epileptology. Boca Raton, Florida: Taylor & Francis CRC Press; 2001. [400].

14. Shorvon, S. Handbook of epilepsy treatment. In Massachusetts. Blackwell Publishing; 2000. [248].

15. Fahn, S. Posthypoxic action myoclonus: Literature review update. Adv Neurol. 1986;43:157–169.

16. Alfradique, I., Vasconcelos, M.M. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65(4B):1266–1271.

17. Auvin, S. Treatment of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(3):227–233.

18. Caicoya, A.G., Serratosa, J.M. Postictal behaviour in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2006;8(3):228–231.

19. Sadleir, L.G., et al. Electroclinical features of absence seizures in childhood absence epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;67(3):413–418.

20. Panayiotopoulos, C.P., et al. Benign childhood focal epilepsies: Assessment of established and newly recognized syndromes. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 9):2264–2286.

21. Doose, H., Baier, W.K. Benign partial epilepsy and related conditions: Multifactorial pathogenesis with hereditary impairment of brain maturation. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;149(3):152–158.

22. Engel, J.J. Report of the ILAE classification core group. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1558–1568.

23. Fetveit, A. Assessment of febrile seizures in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167(1):17–27.

24. Xue, L.Y., Ritaccio, A.L. Reflex seizures and reflex epilepsy. Am J Electroneurodiagnostic Technol. 2006;46(1):39–48.

25. King, D.W., et al. Pseudoseizures: Diagnostic evaluation. Neurology. 1982;32(1):18–23.

26. Boon, P.A., Williamson, P.D. The diagnosis of pseudoseizures. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1993;95(1):1–8.

27. Geyer, J.D., Payne, T.A., Drury, I. The value of pelvic thrusting in the diagnosis of seizures and pseudoseizures. Neurology. 2000;54(1):227–229.

28. Harden, C.L., Burgut, F.T., Kanner, A.M. The diagnostic significance of video-EEG monitoring findings on pseudoseizure patients differs between neurologists and psychiatrists. Epilepsia. 2003;44(3):453–456.

29. Eriksson, K., Kalviainen, R. Pharmacologic management of convulsive status epilepticus in childhood. Expert Rev Neurother. 2005;5(6):777–783.

30. Meierkord, H., et al. EFNS guideline on the management of status epilepticus. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(5):445–450.

31. Riviello, J.J., Jr., et al. Practice parameter: Diagnostic assessment of the child with status epilepticus (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1542–1550.

32. DeLorenzo, R.J., et al. Persistent nonconvulsive status epilepticus after the control of convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1998;39(8):833–840.

33. Towne, A.R., et al. Prevalence of nonconvulsive status epilepticus in comatose patients. Neurology. 2000;54(2):340–345.

34. Bauer, J., et al. Precipitating factors and therapeutic outcome in epilepsy with generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102(4):205–208.

35. Goulden, K.J., et al. Changes in serum anticonvulsant levels with febrile illness in children with epilepsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 1988;15(3):281–285.

36. Zaccara, G., Muscas, G.C., Messori, A. Clinical features, pathogenesis and management of drug-induced seizures. Drug Saf. 1990;5(2):109–151.

37. Ramirez-Lassepas, M., et al. Value of computed tomographic scan in the evaluation of adult patients after their first seizure. Ann Neurol. 1984;15(6):536–543.

38. Phizackerley, P.J., Poole, E.W., Whitty, C.W. Sino-auricular heart block as an epileptic manifestation; a case report. Epilepsia. 1954;3:89–91.

39. Garretson, H.D., Elvidge, A.R. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia with asystole and seizures. Arch Neurol. 1963;8:26–31.

40. Rowland L.P., ed. Merritt’s textbook of neurology, vol 11e. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

41. Walton, J.N. Brain’s diseases of the nervous system, 8th edn. New York: Oxford Medical Publications; 1977. [1277].

42. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology in cooperation with American College of Emergency Physicians. American Association of Neurological Surgeons, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Practice parameter: neuroimaging in the emergency patient presenting with seizure – summary statement. Neurology. 1996;47(1):288–291.

43. Krumholz, A., et al. Practice parameter: Evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2007;69(21):1996–2007.

44. Stroink, H., et al. The first unprovoked, untreated seizure in childhood: A hospital based study of the accuracy of the diagnosis, rate of recurrence, and long term outcome after recurrence. Dutch study of epilepsy in childhood. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64(5):595–600.

45. Hauser, W.A., et al. Seizure recurrence after a first unprovoked seizure. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(9):522–528.

46. Pohlmann-Eden, B., et al. The first seizure and its management in adults and children. BMJ. 2006;332(7537):339–342.

47. Kim, L.G., et al. Prediction of risk of seizure recurrence after a single seizure and early epilepsy: Further results from the MESS trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(4):317–322.

48. Marson, A., et al. Immediate versus deferred antiepileptic drug treatment for early epilepsy and single seizures: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9476):2007–2013.

49. Bautista, R.E., Wludyka, P. Driving prevalence and factors associated with driving among patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9(4):625–631.

50. Verrotti, A., et al. Levetiracetam in absence epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(11):850–853.

51. Posner, E.B., Panayiotopoulos, C.P. The significance of specific diagnosis in the treatment of epilepsies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(11):807.

52. Rowan, A.J., et al. New onset geriatric epilepsy: A randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology. 2005;64(11):1868–1873.

53. Kwan, P., Brodie, M.J. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):314–319.

54. Brodie, M.J. Medical therapy of epilepsy: When to initiate treatment and when to combine? J Neurol. 2005;252(2):125–130.

55. Stephen, L.J. Drug treatment of epilepsy in elderly people: Focus on valproic acid. Drugs Aging. 2003;20(2):141–152.

56. Hirsch, L.J., et al. Predictors of lamotrigine-associated rash. Epilepsia. 2006;47(2):318–322.

57. Claxton, A.J., Cramer, J., Pierce, C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23(8):1296–1310.

58. Leidy, N.K., et al. Seizure frequency and the health-related quality of life of adults with epilepsy. Neurology. 1999;53(1):162–166.

59. Patsalos, P.N., et al. Antiepileptic drugs – best practice guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring: A position paper by the subcommission on therapeutic drug monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49(7):1239–1276.

60. Sheth, S.G., et al. Mortality in epilepsy: Driving fatalities vs other causes of death in patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;63(6):1002–1007.

61. Krauss, G.L., et al. Risk factors for seizure-related motor vehicle crashes in patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 1999;52(7):1324–1329.

62. Austroads. Assessing fitness to drive. Sydney: Austroads Incorporated; 2003.

63. Perucca, E. Birth defects after prenatal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):781–786.

64. Tomson, T., Perucca, E., Battino, D. Navigating toward fetal and maternal health: The challenge of treating epilepsy in pregnancy. Epilepsia. 2004;45(10):1171–1175.

65. Adab, N., et al. Common antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy in women with epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2004. [CD004848].

66. Holmes, L.B., Wyszynski, D.F., Lieberman, E. The AED (antiepileptic drug) pregnancy registry: A 6-year experience. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(5):673–678.

67. Wyszynski, D.F., et al. Increased rate of major malformations in offspring exposed to valproate during pregnancy. Neurology. 2005;64(6):961–965.

68. The EURAP. Study Group. Seizure control and treatment in pregnancy: Observations from the EURAP epilepsy pregnancy registry. Neurology. 2006;66(3):354–360.

69. Morrow, J., et al. Malformation risks of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy: A prospective study from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):193–198.

70. Vajda, F.J., et al. Foetal malformations and seizure control: 52 months data of the Australian Pregnancy Registry. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(6):645–654.

71. Ryan, C.A., Dowling, G. Drowning deaths in people with epilepsy. CMAJ. 1993;148(5):781–784.

72. Arango, M.F., Steven, D.A., Herrick, I.A. Neurosurgery for the treatment of epilepsy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004;17(5):383–387.

73. Cascino, G.D. Neuroimaging in epilepsy: Diagnostic strategies in partial epilepsy. Semin Neurol. 2008;28(4):523–532.

74. The Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. A randomized controlled trial of chronic vagus nerve stimulation for treatment of medically intractable seizures. Neurology. 1995;45(2):224–230.

75. Tellez-Zenteno, J.F., et al. Hippocampal electrical stimulation in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;66(10):1490–1494.

76. Velasco, F., et al. Double-blind, randomized controlled pilot study of bilateral cerebellar stimulation for treatment of intractable motor seizures. Epilepsia. 2005;46(7):1071–1081.

77. Wiebe, S., et al. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(5):311–318.

78. Shaefi, S., Harkness, W. Current status of surgery in the management of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44(Suppl 1):43–47.

79. Rathore, C., et al. Outcome after corpus callosotomy in children with injurious drop attacks and severe mental retardation. Brain Dev. 2007;29(9):577–585.

80. Jea, A., et al. Corpus callosotomy in children with intractable epilepsy using frameless stereotactic neuronavigation: 12-year experience at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25(3):E7.

81. Spencer, S., Huh, L. Outcomes of epilepsy surgery in adults and children. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(6):525–537.

82. Sirven, J.I., Sperling, M., Wingerchuk, D.M. Early versus late antiepileptic drug withdrawal for people with epilepsy in remission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2001. [CD001902].

83. Specchio, L.M., Beghi, E. Should antiepileptic drugs be withdrawn in seizure-free patients? CNS Drugs. 2004;18(4):201–212.

84. Aktekin, B., et al. Withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs in adult patients free of seizures for 4 years: A prospective study. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8(3):616–619.

85. Ranganathan, L.N., Ramaratnam, S. Rapid versus slow withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2006. [CD005003].

86. Feely, M. Clinical review: Fortnightly review drug treatment of epilepsy. BMJ. 1999;318:106–109.

87. Marsan, C.A., Zivin, L.S. Factors related to the occurrence of typical paroxysmal abnormalities in the EEG records of epileptic patients. Epilepsia. 1970;11(4):361–381.

88. Salinsky, M., Kanter, R., Dasheiff, R.M. Effectiveness of multiple EEGs in supporting the diagnosis of epilepsy: An operational curve. Epilepsia. 1987;28(4):331–334.

89. Zivin, L., Marsan, C.A. Incidence and prognostic significance of “epileptiform” activity in the eeg of non-epileptic subjects. Brain. 1968;91(4):751–778.

90. Cavazzuti, G.B., Cappella, L., Nalin, A. Longitudinal study of epileptiform EEG patterns in normal children. Epilepsia. 1980;21(1):43–55.

91. Degen, R. A study of the diagnostic value of waking and sleep EEGs after sleep deprivation in epileptic patients on anticonvulsive therapy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1980;49(5-6):577–584.

92. Boon, P., et al. Interictal and ictal video-EEG monitoring. Acta Neurol Belg. 1999;99(4):247–255.

93. Watemberg, N., et al. Adding video recording increases the diagnostic yield of routine electroencephalograms in children with frequent paroxysmal events. Epilepsia. 2005;46(5):716–719.

94. Jedrzejczak, J., Owczarek, K., Majkowski, J. Psychogenic pseudoepileptic seizures: Clinical and electroencephalogram (EEG) video-tape recordings. Eur J Neurol. 1999;6(4):473–479.