74 Seizures

Etiology and Pathogenesis

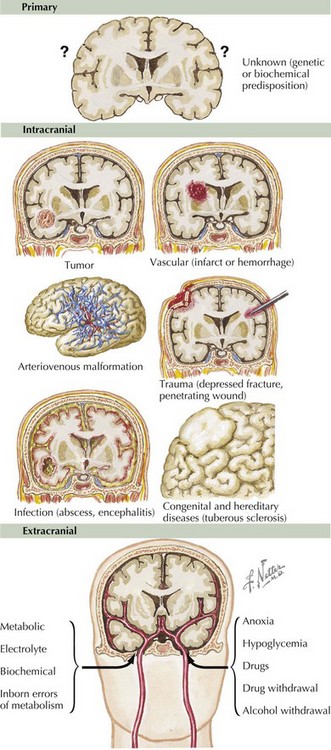

Seizures can arise from many different sources (Figure 74-1). Primary seizures are thought to have a genetic or biochemical origin. Intracranial pathology, including tumor, vascular infarct or hemorrhage, arteriovenous malformation, trauma, infection, or congenital or developmental brain defects, can also result in seizure. They may also be provoked by electrolyte abnormalities (hypoglycemia, hypo or hypernatremia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia), infection, anoxia, certain medications, drug intoxication or withdrawal, kidney or liver failure, and inborn errors of metabolism.

Clinical Presentation

Seizure Classification

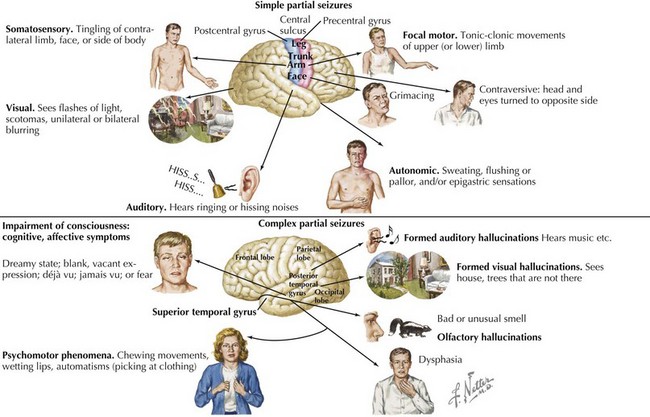

Symptoms of simple partial seizures are often determined by the cortical area involved. These symptoms may be motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychic in nature. For example, those arising from the motor cortex result in rhythmic movements of the contralateral face, arm, or leg. See Figure 74-2 for more examples.

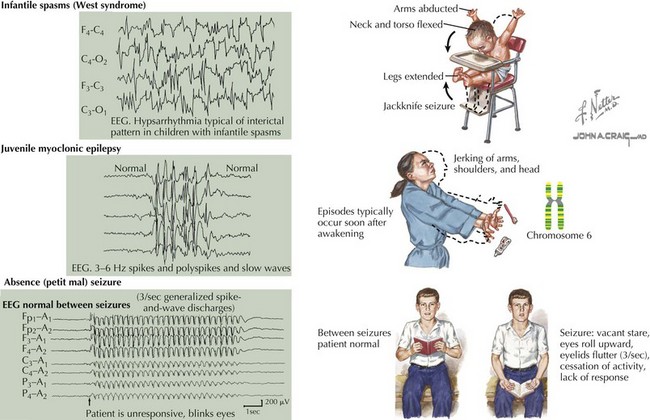

Absence seizures are brief episodes of impaired consciousness with no aura or postictal confusion. They typically last less than 20 seconds and are accompanied by few or no automatisms. Hyperventilation or photic stimulation often precipitates these seizures, which typically begin during childhood or adolescence, although they may persist into adulthood. In children, these seizures may initially go unnoticed and are often associated with decreased school performance or poor attention. The classic ictal electroencephalographic (EEG) correlate of absence seizures consists of 3-Hz generalized spike and slow-wave complexes (Figure 74-3).

Epilepsy Syndromes

Certain patterns of epilepsy in childhood have been further classified into syndromes (Figure 74-3). The diagnosis of these syndromes can further guide treatment choices and help to predict developmental outcome. The etiology may be symptomatic (secondary to a known cause), idiopathic (presumed to be genetic), or cryptogenic (presumed to be symptomatic but with an unknown underlying abnormality).

Evaluation

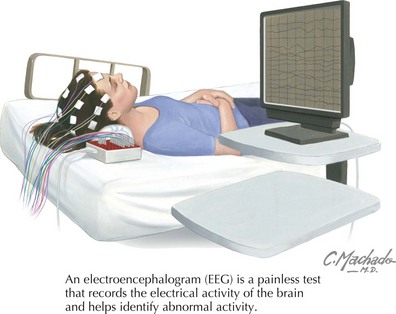

EEG can support a clinical diagnosis of seizure and can help with the classification of seizure type. However, 50% of patients with epilepsy may have a normal interictal EEG. Certain techniques, such as hyperventilation and photic stimulation, may bring out abnormalities, particularly in certain epilepsy syndromes. Sometimes prolonged ambulatory or inpatient video EEG are required to capture an event and diagnosis of a seizure, differentiate from nonepileptic events, or clarify seizure type (Figure 74-4).

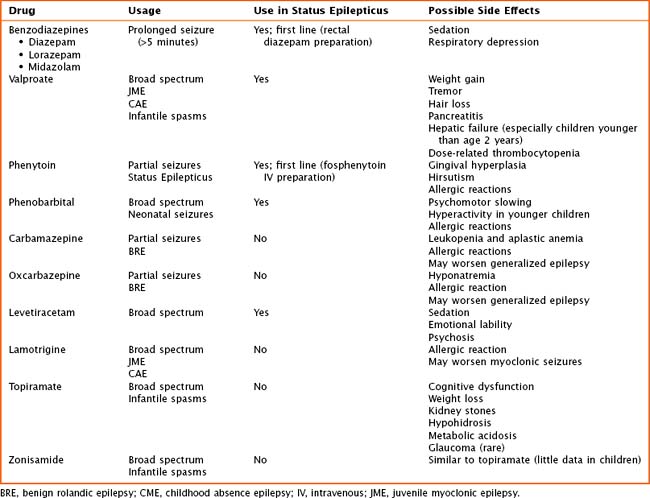

Management

Hirtz D, Berg A, Bettis D, et al. Practice parameter: treatment of the child with a first unprovoked seizure: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2003;60(2):166-175.

Riviello JJJr, Ashwal S, Hirtz D, et al. Practice parameter: diagnostic assessment of the child with status epilepticus (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1542-1550.

Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures American Academy of Pediatrics. Febrile seizures: clinical practice guideline for the long-term management of the child with simple febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1281-1286.