Chapter 39 SEIZURES

Medications and Toxins Associated with Seizures

Anticonvulsants (from withdrawal)

Causes of Seizures

Neurologic, Congenital, or Developmental

• Benign partial epilepsy of childhood

• Degenerative cerebral disease

• Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

• Infantile spasms (West’s syndrome)

Key Historical Features

Events immediately before the onset of the episode

Events immediately before the onset of the episode

Thorough description of the seizure

Thorough description of the seizure

History of seizure disorder, including:

History of seizure disorder, including:

Birth history and perinatal complications

Birth history and perinatal complications

Cognitive behavioral history, especially:

Cognitive behavioral history, especially:

Family history, especially family history of seizures

Family history, especially family history of seizures

Key Physical Findings

Vital signs, including temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure

Vital signs, including temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure

Measurement of head circumference in infants

Measurement of head circumference in infants

General evaluation for toxic appearance or pallor

General evaluation for toxic appearance or pallor

Head examination for dysmorphic features, syndromic facies, signs of trauma, a bulging fontanelle, or the presence of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt

Head examination for dysmorphic features, syndromic facies, signs of trauma, a bulging fontanelle, or the presence of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt

Eye examination for papilledema or retinal hemorrhages

Eye examination for papilledema or retinal hemorrhages

Ear examination for hemotympanum

Ear examination for hemotympanum

Neck examination for signs of meningeal irritation

Neck examination for signs of meningeal irritation

Abdominal examination for hepatosplenomegaly

Abdominal examination for hepatosplenomegaly

Skin examination for petechial rash, unexplained bruising, café-au-lait spots (neurofibromatosis), adenoma sebaceum or ash leaf spots (tuberous sclerosis), or port wine stains (Sturge-Weber syndrome)

Skin examination for petechial rash, unexplained bruising, café-au-lait spots (neurofibromatosis), adenoma sebaceum or ash leaf spots (tuberous sclerosis), or port wine stains (Sturge-Weber syndrome)

Thorough neurologic examination for focal or lateralizing deficits

Thorough neurologic examination for focal or lateralizing deficits

Suggested Work-up of Pediatric Seizures

| Bedside glucose test | To evaluate for hypoglycemia |

| Specific drug level(s) | Should be obtained in patients who are taking anticonvulsant medications |

| Electrolytes, calcium, magnesium | Indicated in patients with a history of diabetes or metabolic disorder, dehydration, excess free water intake, prolonged seizure, an altered level of consciousness, and those younger than 6 months because of an increased risk of electrolyte disturbances |

| Complete blood count (CBC) | If an infectious cause of the seizure is suspected |

| Toxicology screen | If toxin exposure is suspected |

| Lumbar puncture | Should be considered in patients with meningeal signs, altered mental status, a prolonged postictal period, a petechial rash, or in neonatal seizures |

| Brain computed tomography (CT) | Should be performed in patients with: |

Additional Work-up of Pediatric Seizures

| Blood amino acids, lactate, pyruvate, ammonia, and urine organic acids | If an inborn error of metabolism is suspected |

| Emergent EEG | For patients in whom the diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus is suspected or in those with refractory seizure activity |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | More sensitive than a cranial CT scan for the detection of certain tumors and vascular malformations |

| HIV test | If HIV infection is suspected |

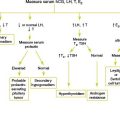

Suggested Work-up of Neonatal Seizures

1. Blumstein M.D. Childhood seizures. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25(4):1061–1086.

2. Burkhard P.R., Burkhardt K., Haenggeli C.A., Landis T. Plant-induced seizures: reappearance of an old problem. J Neurol. 1999;246:667–670.

3. Datta A., Sinclair D.B. Benign epilepsy of childhood with rolandic spikes: typical and atypical variants. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36(3):141–145.

4. Friedman M.J., Sharieff G.Q. Seizures in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53(2):257–277.

5. Froberg B., Ibrahim D., Furbee R.B. Plant poisoning. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25(2):375–433.

6. Wills B., Erickson T. Chemically induced seizures. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26(1):185–209.