99 Seizures

• Seizures are classified by the clinical finding of abnormal electrical impulses within the cerebral cortex.

• Direct morbidity and mortality are the result of inadequate cerebral perfusion of oxygen and glucose to the brain, as well as secondary trauma.

• Serum glucose levels should be checked in all seizure patients immediately.

• Emergency department treatment is directed at urgent cessation of seizures, prevention of further activity, and diagnosis and correction of the underlying cause.

• Intravenous benzodiazepines are the initial treatment of most seizures.

• Isoniazid can cause intractable seizures with an overdose; the antidote is pyridoxine.

• Eclamptic seizures, most common in the third trimester, can also occur postpartum; the antidote is intravenous magnesium sulfate.

• One third of eclamptic woman do not have the classic triad of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema.

• Most chronic seizure patients can be discharged home safely after emergency department evaluation and correction of anticonvulsant levels if needed.

• Patients with seizure disorders should have adequate control and close follow-up with a neurologist before driving vehicles or operating machinery.

Pathophysiology

The specific seizure activity is determined by the area in the brain involved (Box 99.1). Some of these abnormal electrical discharges may remain localized, whereas others may involve larger areas of the brain. Subsequently, the resultant clinical spectrum includes isolated focal motor activity, as well as generalized motor and sensory abnormalities, including altered mental status and behavioral changes.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

If available, the previous medical history may reveal risk factors (Box 99.2) associated with the development of seizures. The history can be obtained from the patient (after normalization of mental status), family, primary care physicians, old medical records, or emergency medical service (EMS) personnel.

Box 99.2 Differential Diagnosis of Conditions Resulting in Seizurelike Symptoms

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The most common serious condition that can be misinterpreted as a seizure is syncope.5 There may be important clinical signs or preceding events that can help differentiate these two entities (Table 99.1). In many circumstances patients will be unable to provide critical information, so it is important to try to obtain an accurate description from anyone who witnessed the event (e.g., family, coworkers, EMS personnel). Aside from syncope, several other medical conditions need to be included in the differential diagnosis of seizures (Boxes 99.3 and 99-4; Table 99.2).

| SEIZURES (SPECIFIC) | NONSPECIFIC (CAN OCCUR IN BOTH) SYMPTOMS | SYNCOPE (SPECIFIC) |

|---|---|---|

Box 99.3 Differential Diagnoses of Secondary Seizures

Box 99.4 Factors Precipitating Seizures

| DIAGNOSTIC TEST | COMMENT |

|---|---|

| Complete blood count | May reveal anemia or an infectious process |

| Electrolytes (including Ca and Mg) | Hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia can be associated with seizures and should be corrected |

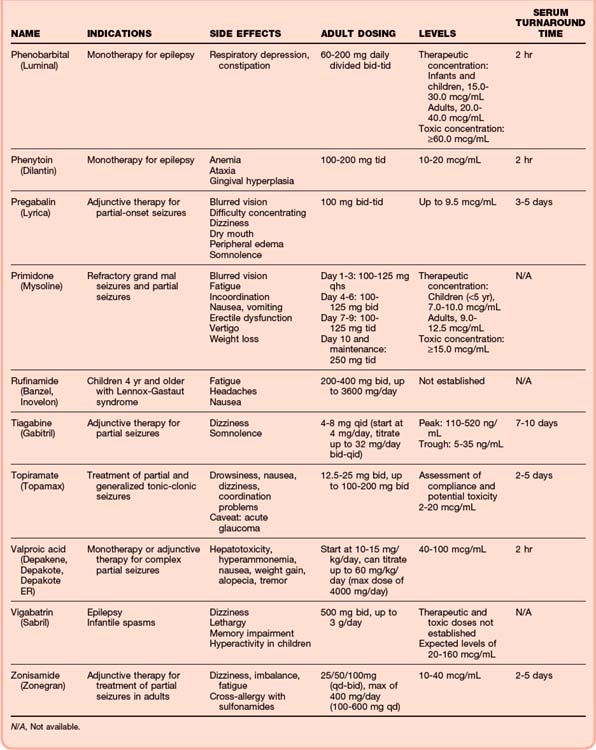

| Anticonvulsants—serum levels | For patients currently taking anticonvulsants, see Table 99.5 |

| Pregnancy test (women of childbearing age) | Rule out eclamptic seizures |

| Serum glucose | Should be determined immediately and corrected before further management |

| Computed tomography of the brain | |

| Spinal tap | In the event of suspected CNS infection or HIV/AIDS population |

| Electroencephalography | Only if intubated in the emergency department or in a patient with persistent unconsciousness with an identifiable cause (rule out non–tonic-clonic status) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | May reveal additional CNS diagnosis and identify smaller CNS lesions |

| Electrocardiography | Rule out dysrhythmias or drug toxicity (anticholinergics, sodium channel blockade, cyclic antidepressants) Rule out a prolonged QTc or widened QRS interval |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

If an overdose is suspected, both blood and urine toxicologic screens should be performed.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be obtained in every patient with a first onset of seizures or with suspicion of a cardiac cause of decreased central nervous system (CNS) perfusion. In addition to ischemia, the most important disorders that have to be excluded are related to conduction abnormalities and consequent dysrhythmias. ECGs are used to evaluate widening of the QRS complex because of sodium channel blockade after an overdose of certain medications, particularly cyclic antidepressants. More specific changes on the ECG, such as a terminal 400-msec R wave in the aVR lead, can also assist in identifying toxicity from cyclic antidepressants. A prolonged QTc interval can be found with overdose of citalopram (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with proconvulsive properties). Tachyarrhythmias are often seen in the setting of cocaine and methylxanthine toxicity (theophylline, caffeine) (Box 99.5).

Computed tomography (CT) of the brain should be performed in every patient with a first onset of seizures and in those with persistent change in mental status, focal neurologic deficit, or suspicion of an organic intracerebral lesion. Early CT scanning is essential for identifying surgically correctable causes. If there is a concern that trauma occurred, CT can be used to rule out cervical spine and intracerebral injury (Box 99.6).

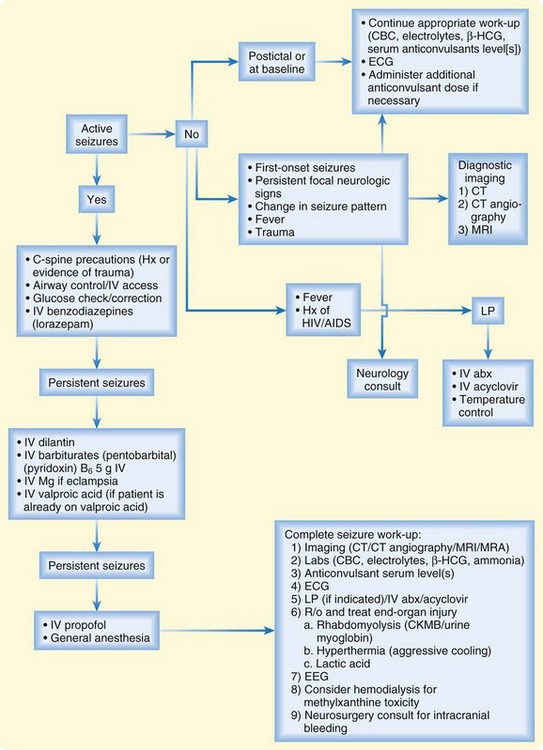

If patient is transported by EMS, multiple steps in the treatment (Fig. 99.1) protocol can be initiated and completed by EMS personnel, including administration of anticonvulsants, airway protection, correction of glucose, and elicitation of the initial history, including drug exposure. it is essential that an attempt be made to control seizure activity immediately on arrival at the ED, so discussion of treatment will occur simultaneously with discussion of the diagnostic approach. Maintenance of adequate cerebral perfusion and consequent oxygen and glucose supply to the brain is the goal of treatment.

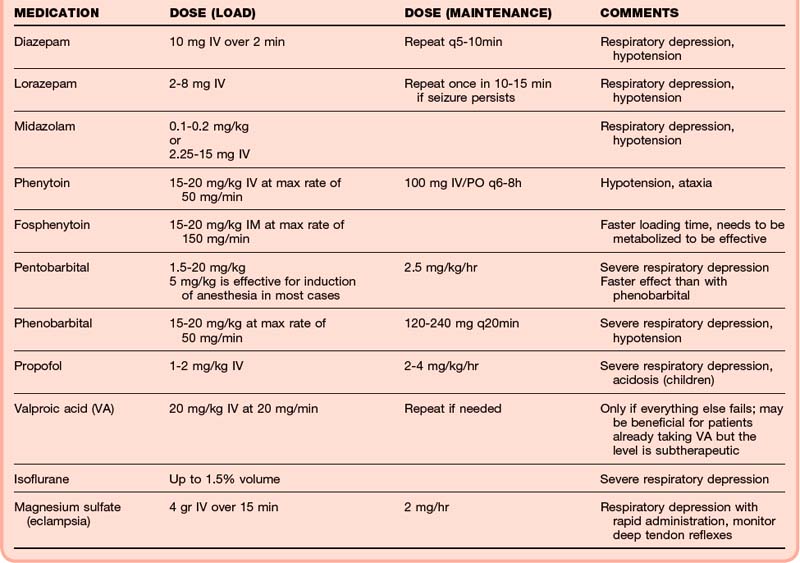

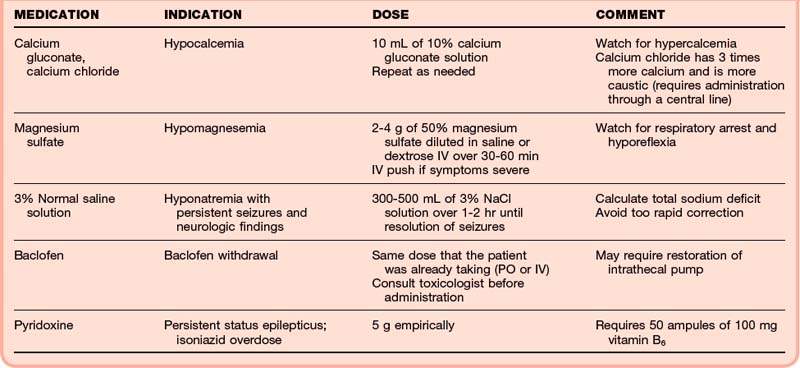

Benzodiazepines should be administered immediately because they have been shown to control the majority of seizures regardless of cause through an increase in GABA activity. Studies have shown that lorazepam (Ativan, 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg up to a maximum of a 4-mg initial dose) is more effective than diazepam (Valium, 5 to 15 mg IV) for the initial control of seizures, although both agents are acceptable.2,4 If intravenous access is difficult, intramuscular or rectal administration of valium (Diastat, rectal form of valium, 0.2 mg/kg up to 20 mg PR) or lorazepam (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg IM) is an alternative. Intranasal midazolam (Versed) has also been used. Continued seizure activity should be treated with a second dose of a benzodiazepine, along with the addition of a second agent (e.g., barbiturate, propofol, pyridoxine/vitamin B6) and attention to disorders inciting the seizure (e.g., increased intracranial pressure, CNS infection, eclampsia, drug-related seizures) (Table 99.3).

Patients with chronic seizures who have a typical event may require only evaluation of the antiepileptic level and triggering factors. However, new organic pathology that may lower the seizure threshold (e.g., infection, electrolyte abnormality, trauma) should be excluded. Any precipitating factors that may unmask a chronic seizure disorder or explain an increase in seizure reoccurrence in patients with therapeutic levels of anticonvulsants should be identified (see Box 99.4). In the absence of concomitant pathology, the majority of patients with chronic seizures can be discharged home if they return to baseline.

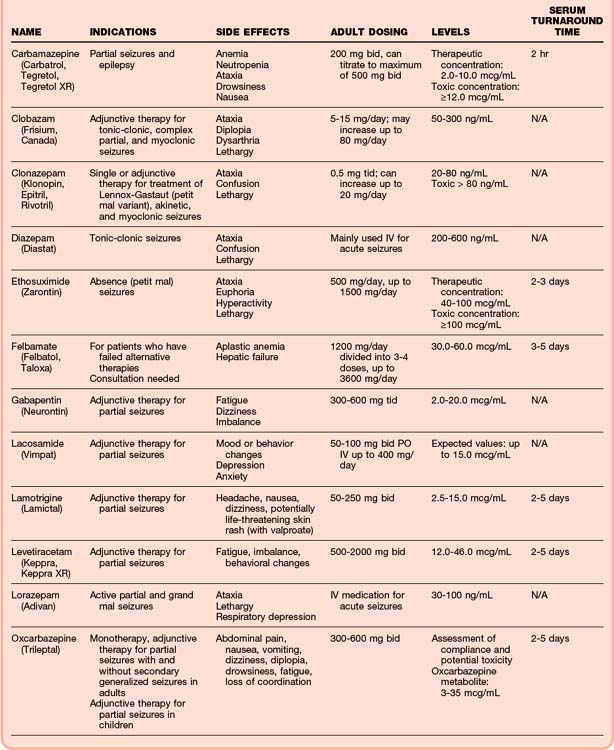

Patients who are undergoing chronic anticonvulsant treatment should receive an additional oral dose before discharge if the level is found to be subtherapeutic. It is also reasonable to give a dose of one of the newer anticonvulsants in the ED to patients who are noncompliant with treatment (Table 99.4).

Special Circumstances

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

People infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may have a CNS mass or infection as a cause of the seizure. This can be the first manifestation of AIDS. HIV-positive patients who have a seizure require a CT scan and, if negative, a lumbar puncture. HIV encephalopathy or meningitis must be considered (Box 99.7).

Box 99.7 Causes of Seizures in the Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Population

Drug- And Toxin-Induced Seizures

Any drug that decreases GABA activity in the CNS can cause seizures. Drug-related seizures are a result of either overstimulation (glutamate) or lack of inhibition (GABA withdrawal) of electrical brain activity. Treatment is generally directed at increasing GABA activity with benzodiazepines. However, certain drugs are associated with particular types of toxicities that may require specific treatments or antidotes (Tables 99.5 and 99.6).

| MEDICATION/DRUG | COMMENT |

|---|---|

| Camphor | Brief, tonic-clonic seizures, usually self-limited |

| Cocaine Amphetamines Phencyclidine |

Control agitation and hyperthermia aggressively |

| Treatment of choice: benzodiazepines | |

| Cyclic antidepressants | Can be excluded with electrocardiogram |

| Severe toxicity can cause cardiac dysrhythmias | |

| Treatment with bicarbonate will control electrocardiographic changes, but not the seizures | |

| Benzodiazepines are the drug of choice | |

| Isoniazid | Suspect isoniazid in patients with intractable seizures not responsive to benzodiazepines |

| Treat with intravenous vitamin B6 | |

| Lindane | Usually ingestion of topical preparation |

| MDMA (Ecstasy) | Usually associated with hyponatremia |

| Morning after “rave” party | |

| Fluid restriction is usually sufficient therapy | |

| Strychnine | Consciousness preserved |

| Pseudoseizures | |

| Theophylline | Adenosine antagonism |

| Wide pulse pressure | |

| Tachycardia | |

| Hypokalemia | |

| Hyperglycemia | |

| Possible hemodialysis for intractable seizures |

MDMA, 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

Other Medications Typically Associated with Seizures (table 99.7)

Cyclic Antidepressants

| CLASS | REPRESENTATIVE AGENTS |

|---|---|

| Analgesics | Tramadol |

| Propoxyphene | |

| Meperidine | |

| Anesthetics | General: enflurane |

| Local: lidocaine, bupivacaine | |

| Anthelmintics | Albendazole |

| Antiasthmatics | Terbutaline |

| Theophylline | |

| Antibacterials | Erythromycin |

| Fluoroquinolones | |

| Anticholinergics | Scopolamine |

| Anticholinesterases | Physostigmine |

| Antidepressants | Cyclic antidepressants |

| Citalopram | |

| Wellbutrin | |

| Antifungals | Amphotericin B |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine |

| Antimalarials | Quinine |

| Antipsychotics | Haloperidol |

| Antivirals | Amantadine |

| Contrast agents | Iohexol |

| Hypoglycemics | Chlorpropamide |

| Immunosuppressives | Azathioprine |

| Miscellaneous | Baclofen |

| Flumazenil | |

| Nicotine | |

| NSAIDs | Mefenamic acid |

| Sympathomimetics | Amphetamines |

| Ephedrine | |

| Vaccines | DTP |

DTP, Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis vaccine; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Every patient with persistent seizures, change in mental status, or underlying medical condition that requires hospital treatment (e.g., sepsis, overdose, trauma) should be admitted. Patients in SE should be admitted to an intensive care setting (Box 99.8).

Box 99.8 Admission Criteria for Patients with Seizures

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Subtherapeutic levels should be documented in addition to the planned strategy to achieve therapeutic serum levels in a reasonable time frame.

If computed tomography and laboratory work are deemed unnecessary, adequate documentation should support the medical reasoning and clinical findings.

Discussion with the neurology service should be documented with respect to diagnosis, treatment, and close follow-up.

Patients with a chronic seizure disorder can be discharged if they return to their normal baseline neurologic level (Box 99.9). If the drug level is found to be subtherapeutic, an additional dose of antiepileptics should be given prior to discharge. Before discharge, patients may inquire about their prognosis. In the absence of precipitating factors, secondary seizures may be avoidable in the future, but there will always be some risk, depending on the underlying condition and lifestyle. Patients should avoid sleeplessness, heavy alcohol use, and other physiologic stressors that can alter seizure thresholds.

Box 99.9 Discharge Criteria

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Patients with status epilepticus should be treated aggressively with the administration of multiple medications at once. Clinician should be aware that administration of phenytoin and phenobarbital is rate dependent and that patients may continue to have seizures for 30 minutes before effective serum levels are achieved.

Patients with cocaine abuse, persistent seizures, and a recent history of travel abroad should be evaluated for body packing and decontaminated by whole-bowel irrigation.

Not recognizing that a patient is pregnant (or postpartum) may lead to delayed treatment and obstetrics consultation.

Patients with seizures should be counseled to not drive and should be accompanied because a recurrent seizure is possible.

Timely administration of antibiotics and antiviral medication in patients with central nervous system infection can improve survival and reduce morbidity.

1 ACEP Clinical Policies Committee; Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Seizures. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with seizures. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:605–625.

2 Engel Jr, J., Starkman S. Overview of seizures. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1994;12:895–923.

3 Walker MC. The epidemiology and management of status epilepticus (seizure disorders). Curr Opin Neurol. 1988;11:149–154.

4 Dunn MJ, Breen DP, Davenport RJ, et al. Early management of adults with an uncomplicated first generalised seizure. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:237–242.

5 McKean A, Vaughan C, Delanty N. Seizure versus syncope. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:171–180.

6 Chen DK, So YT, Fisher RS, Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Use of serum prolactin in diagnosing epileptic seizures: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2005;65:668–675.

7 Takayanagui OM, Odashima NS. Clinical aspects of neurocysticercosis. Parasitol Int. 2006;55(Suppl):S111–S115.