Objectives

• Explain the differences among light, moderate, and deep levels of sedation.

• Describe the role of standardized assessment tools to determine sedation requirements.

• Compare and contrast the pharmacological agents used to provide sedation.

• List the risk factors for development of delirium in critical illness.

• Describe the management of delirium tremens in critical illness.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

One of the challenges facing clinicians is how to provide a therapeutic healing environment for patients in the alarm-filled, emergency-focused critical care unit. Many critical care patients demonstrate some degree of agitation and discomfort caused by painful procedures, invasive tubes, sleep deprivation, fear, anxiety, and physiological stress.

Clinical practice guidelines were developed by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) to increase awareness of these issues in the critically ill.1 The goal is to find a balance between providing compassionate patient care and avoiding the perils of oversedation.

Sedation

Sedation Scales

The use of scoring systems to assess and record levels of sedation and agitation is now strongly recommended.1 Four frequently used scales are the Ramsay Scale,2 the Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS),3 the Motor Activity Assessment Scale (MAAS),4 and the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS)5,6 (Table 9-1). Because individuals do not metabolize sedative medications at the same rate, the use of a standardized scale can ensure that continuous infusions of sedatives such as propofol or lorazepam are titrated to a specific goal. Collaboratively, the critical care team must determine which level of sedation is most appropriate for each individual patient.1

TABLE 9-1

| SCORE | DESCRIPTION | DEFINITION | |

| Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS)* | |||

| 7 | Dangerously agitated | Pulls at endotracheal tube (ETT), tries to remove catheters, climbs over bed rail, strikes at staff, thrashes side to side | |

| 6 | Very agitated | Does not calm despite frequent verbal reminding of limits, requires physical restraints, bites ETT | |

| 5 | Agitated | Anxious or mildly agitated, attempts to sit up, calms down to verbal instructions | |

| 4 | Calm and cooperative | Calm, awakens easily, follows commands | |

| 3 | Sedated | Difficult to arouse, awakens to verbal stimuli or gentle shaking but drifts off again; follows simple commands | |

| 2 | Very sedated | Arouses to physical stimuli but does not communicate or follow commands; may move spontaneously | |

| 1 | Unarousable | Minimal or no response to noxious stimuli; does not communicate or follow commands | |

| Motor Activity Assessment Scale (MAAS)† | |||

| 6 | Dangerously agitated | No external stimulus required to elicit movement; is uncooperative, pulls at tubes or catheters, thrashes side to side, strikes at staff, tries to climb out of bed, does not calm down when asked | |

| 5 | Agitated | No external stimulus required to elicit movement; attempts to sit up or move limbs out of bed, does not consistently follow commands (e.g., will lie down when asked but soon reverts back to attempts) | |

| 4 | Restless and cooperative | No external stimulus required to elicit movement; picks at sheets or tubes or uncovers self; follows commands | |

| 3 | Calm and cooperative | No external stimulus required to elicit movement; adjusts sheets or clothes purposefully; follows commands | |

| 2 | Responsive to touch or name | Opens eyes, raises eyebrows, or turns head toward stimulus; or, moves limbs when touched or when name loudly spoken | |

| 1 | Responsive only to noxious stimulus | Opens eyes, raises eyebrows, or turns head toward stimulus; or, moves limbs with noxious stimulus | |

| 0 | Unresponsive | Does not move with noxious stimulus | |

| Ramsey Scale‡ | |||

| 1 | Awake | Anxious; agitated and/or restless | |

| 2 | Cooperative, oriented, and tranquil | ||

| 3 | Responds only to commands | ||

| 4 | Asleep | Brisk response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus | |

| 5 | Sluggish response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus | ||

| 6 | No response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus | ||

| Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS)§,¶ | |||

| +4 | Combative | Overtly combative, violent, immediate danger to staff | |

| +3 | Very agitated | Pulls or removes tube(s) or catheter(s); aggressive | |

| +2 | Agitated | Frequent nonpurposeful movement, fights ventilator | |

| +1 | Restless | Anxious but movements not aggressive or vigorous | |

| 0 | Alert and calm | ||

| −1 | Drowsy | Not fully alert, but has sustained awakening (eye-opening/eye contact) to voice (≥10 seconds) | } Verbal Stimulation |

| −2 | Light sedation | Briefly awakens with eye contact to voice (<10 seconds) | |

| −3 | Moderate sedation | Movement or eye opening to voice (but no eye contact) | |

| −4 | Deep sedation | No response to voice, but movement or eye opening to physical stimulation | } Physical Stimulation |

| −5 | Unresponsive | No response to voice or physical stimulation | |

*Riker RR, et al: Prospective evaluation of the Sedation-Agitation Scale for adult critically ill patients, Crit Care Med 27(7):1325, 1999.

†Devlin JW, et al: Motor Activity Assessment Scale: a valid and reliable sedation scale for use with mechanically ventilated patients in an adult surgical intensive care unit, Crit Care Med 27(7):1271, 1999.

‡Ramsay MA, et al: Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone, Br Med J 2(5920):656, 1974.

§Sessler CN, et al: The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166(10):1338, 2002.

¶Ely EW, et al: Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS), JAMA 289(22):2983-2991, 2003.

The first step in assessing the agitated patient is to rule out any sensations of pain.1 Clinical assessment is more challenging when the patient is obtunded or has an artificial airway in place. If the patient can communicate, the verbal pain scale of 0 to 10 is very useful. If the patient is intubated and cannot vocalize, pain assessment becomes considerably more complex. After medication for pain has been provided, the next step is to determine the minimum level of sedation required (Box 9-1). The SCCM guidelines recommend that all critically ill, intubated, mechanically ventilated patients have stated goals for analgesia and sedation1 (Figure 9-1). The use of validated assessment scales is advised (see Table 9-1).

Complications of Sedation

Oversedation is recognized as a state of unintended patient unresponsiveness in which the patient resides in a state of suspended animation resembling general anesthesia. Prolonged deep sedation is associated with significant complications of immobility, including pressure ulcers, thromboemboli, gastric ileus, nosocomial pneumonia, and delayed weaning from mechanical ventilation.

Too little sedation is equally hazardous. Most nurses have experienced the challenge of caring for a patient who unexpectedly removes the endotracheal or nasogastric tube. Unplanned extubation in restless, anxious, agitated patients occurs in 8% to 10% of intubated patients after an average of 3.5 days in the critical care unit. Six percent of self-extubation events cause significant complications, including aspiration, dysrhythmias, bronchospasm, and bradycardia.7

Pharmacological Management of Sedation

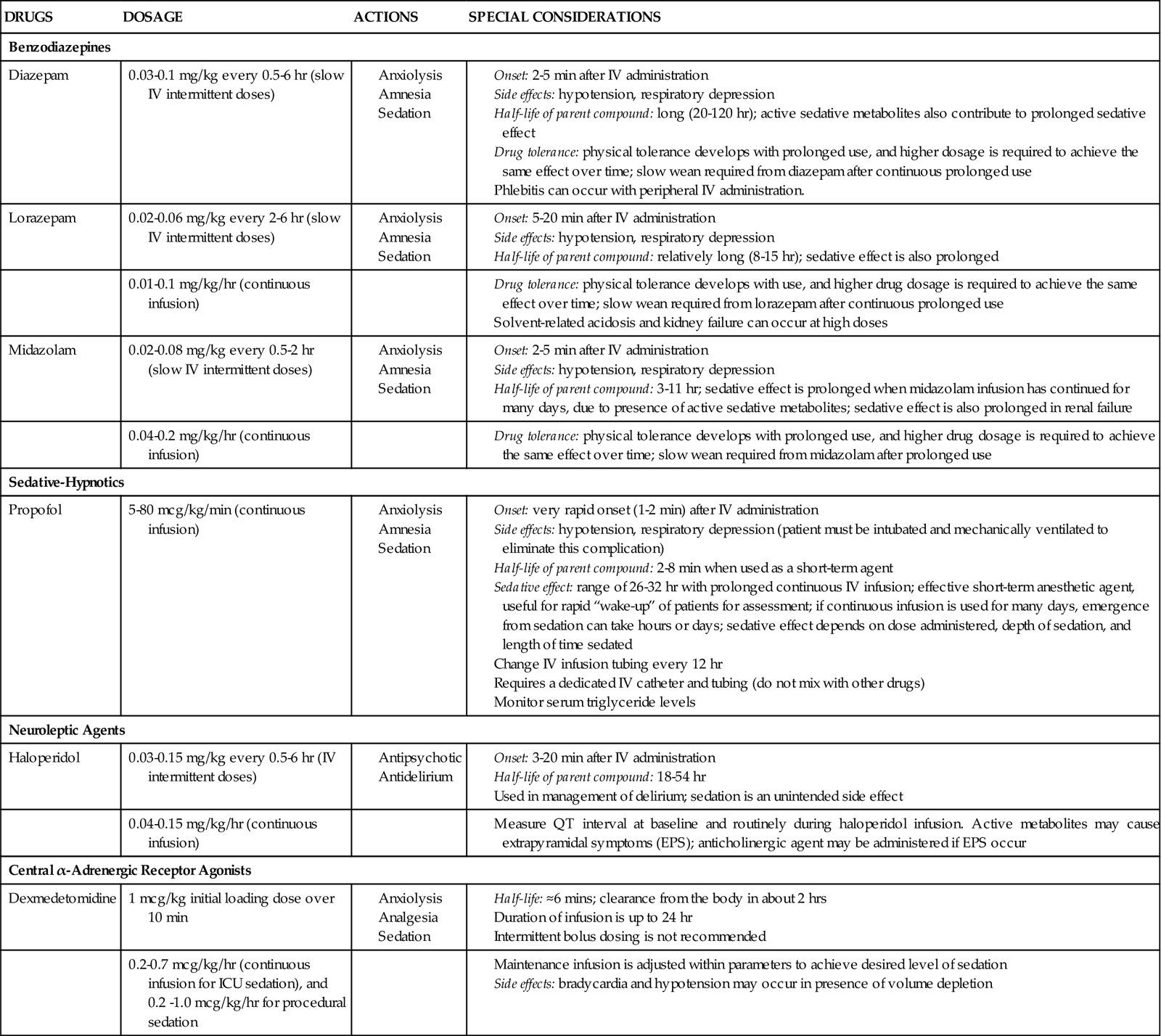

Several categories of sedatives are available. If the patient is experiencing pain, analgesia must be administered in addition to any sedative agents. Sedative agents include the benzodiazepines, sedative-hypnotic agents such as propofol, and the central alpha agonists (Table 9-2).1

TABLE 9-2

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENt: Sedation

Data from: Jacobi J, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult, Crit Care Med 30(1):119, 2002. http://www.precedex.com/safety-information/. Accessed 2/2/2011.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines have powerful amnesic properties that inhibit reception of new sensory information.1,7 Benzodiazepines do not confer analgesia. The most frequently used critical care benzodiazepines are diazepam (Valium), midazolam (Versed), and lorazepam (Ativan). Midazolam is recommended for control of acute short-term agitation because its intravenous onset of action is within 3 minutes (see Figure 9-1.) However, when midazolam is administered for longer than 24 hours as a continuous infusion, the sedative effect is prolonged by its active metabolites.1

The 2002 SCCM clinical guidelines1 recommend a continuous infusion of lorazepam if long-term sedation is needed for a mechanically ventilated patient (see Figure 9-1). One advantage of lorazepam is that it does not have active metabolites that contribute to the overall sedative effect. Disadvantages to use of lorazepam include more days on the ventilator and an increased risk of delirium.8–10

The major unwanted side effects associated with the benzodiazepines are dose-related respiratory depression and hypotension. If needed, flumazenil (Romazicon) is the antidote used to reverse benzodiazepine overdose in symptomatic patients.7 Flumazenil should be avoided in patients with benzodiazepine dependence, because rapid withdrawal can induce seizures.7,11

Sedative-Hypnotic Agents

Propofol is classified as a sedative-hypnotic. It is also used as an intravenous general anesthetic agent. At high doses, propofol is intended to produce a state of general anesthesia in the operating room.12 In the critical care unit, propofol is prescribed as a continuous infusion at lower doses (5 to 80 mcg/kg/min)1 to induce a state of deep sedation in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients.12 The clinical advantage of propofol is its rapid onset of action (about 30 seconds), very short half-life with initial use (2 to 4 minutes), and rapid elimination from the body (30 to 60 minutes).12,13 It does not have active metabolites.13 Propofol is not a reliable amnesic, and patients sedated with only propofol can have vivid recollections of their experiences. It is important to add an opiate, such as fentanyl, to ensure adequate pain control and amnesia.

Propofol related infusion syndrome (PRIS) is a rare complication associated with prolonged high-dose propofol administration.14 It occurs more commonly in children than in adult critically ill patients. For additional information, see Table 9-2 and Propofol Priority Medications Box.

Central Alpha Agonists

Two central α-adrenergic agonists with sedative properties are available. Dexmedetomidine (Precedex) is an intravenous α2-agonist that is approved for continuous infusion as a short-term sedative (<24 hours) in mechanically ventilated patients. Dexmedetomidine confers sedation and analgesic effects without respiratory depression.15 This has made it useful in weaning patients from short-term ventilation after cardiac surgery.16 Dexmedetomidine has also been used for patients on noninvasive mask ventilation.17

Dexmedetomidine is prescribed with a loading dose of 1.0 mcg/kg over 10 minutes, followed by a continuous infusion of 0.4 mcg/kg (range 0.2 to 0.7 mcg/kg/hr).15 Dexmedetomidine has a short half-life (6 minutes) and is eliminated from the body in about 2 hours.15 Elimination from the body is dramatically slowed if the patient has liver failure. For additional information, see Table 9-2 and Dexmedetomidine Priority Medications Box. Clonidine (Catapres) is an older α2-agonist, that may be administered as a transdermal patch, as adjunctive therapy, for patients with alcohol use disorder; it is not used for sedation.

The choice of sedative is highly specific to the patient and the situation. If the need is for short-term sedation (<24 hours), the most frequently used sedatives are midazolam or propofol.1 Both drugs may be combined with a short-acting opioid analgesic (e.g., fentanyl). If the need is for intermediate-term sedation (1 to 3 days), the most frequently prescribed drugs again are propofol and midazolam, plus an opiate. If the need is for long-term sedation, the recommended agent is lorazepam.1

Preventing Sedative Dependence and Withdrawal

The question of which drugs to use for prolonged sedation is complex. Some critically ill patients are mechanically ventilated and seriously ill for weeks or months. Sedation and analgesia are administered to aid the patient in tolerating the ventilator and other procedures. Over time patients become physically and psychologically dependent; when the drug dosage is reduced, they may become physically agitated (Table 9-3).

TABLE 9-3

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF SEDATIVE OR ANALGESIC DRUG WITHDRAWAL*

| SYSTEM | OPIATE WITHDRAWAL | BENZODIAZEPINE WITHDRAWAL† |

| Neurological | Delirium, tremors, seizures | Agitation, anxiety, delirium, tremors, myoclonus, headache, seizures, fatigue, paresthesia, sleep disturbances |

| Sensory | Dilation of pupils, teary eyes, irritability, increased sensitivity to pain, sweating, yawning | Increased sensitivity to light/sound, sweating |

| Musculoskeletal | Cramps, muscle aches | Muscle cramps |

| Gastrointestinal | Vomiting, diarrhea | Nausea, diarrhea |

| Respiratory | Tachypnea | Tachypnea |

*Data on propofol is limited, but withdrawal symptoms after prolonged use are similar to those of the benzodiazepines.3

Physical signs of sedative withdrawal may include agitation with increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Other notable symptoms are lack of self-awareness, unawareness of surroundings, very short-term memory for information, irritability, anxiety, confusion, delirium, and even seizures.1 Patients may pull at the tubes, attempt to climb out of bed, and represent a danger to themselves, the nurse, and family visitors.

Sedation Vacation

One innovative strategy to avoid the pitfalls of sedative dependence and withdrawal is a planned strategy to turn off the sedative infusions once each day. This intervention has been given several names, including drug holiday, sedation vacation, and spontaneous awakening trial. When the patient is hemodynamically stable without contraindications to ventilator weaning, sedation interruption has been shown to shorten time to extubation.18–20 At a scheduled time, all sedative drugs are stopped. Sometimes analgesic drugs are also stopped, depending on the hospital’s protocol. The patient is allowed to regain consciousness for clinical assessment using a standardized instrument such as the RASS (see Table 9-1).18–20 The patient is carefully monitored, and when awareness is attained, an assessment of level of consciousness and neurological function is performed. If the patient becomes agitated, it is essential that a protocol be in place for the nurse to restart the sedatives, plus opiates if applicable. One protocol scheduled the daily interruption of sedatives in the morning and recommended, after a full assessment, restarting the sedative and opiate infusions at 50% of the previous morning dose and adjusting upward until the patient was comfortable.19

An important nursing responsibility is ongoing assessment of patients’ level of consciousness to avert complications during sedative or analgesic drug withdrawal (Table 9-3). If the patient is seriously agitated, it is vital to consult with the physician and pharmacist to establish an effective treatment plan that will allow safe weaning from sedative drugs (see Table 9-1).

Delirium

Delirium represents a global impairment of cognitive processes, usually of sudden onset, coupled with disorientation, impaired short-term memory, altered sensory perceptions (i.e., hallucinations), abnormal thought processes, and inappropriate behavior. Delirium is more prevalent than generally recognized; it is difficult to diagnose in the critically ill patient and represents acute brain dysfunction caused by sepsis, critical illness, or dysfunction of other vital organs (Box 9-2). The incidence of delirium ranges from 60% to 85% among mechanically ventilated patients.21 Delirium increases hospital stay and mortality rates for patients who are mechanically ventilated.22 The increased mortality remains even after controlling for associated variables such as coma and administration of sedatives and analgesics.22

When patients are agitated, restless, and pulling at tubes and lines, they are often identified as being delirious. In this scenario, delirium may be described as “ICU psychosis” or “sundowner syndrome.” However, the delirious patient is not always agitated, and it is much more difficult to detect delirium when the patient is physically calm.1,23 Provision of adequate analgesia is an essential component of delirium prevention.1

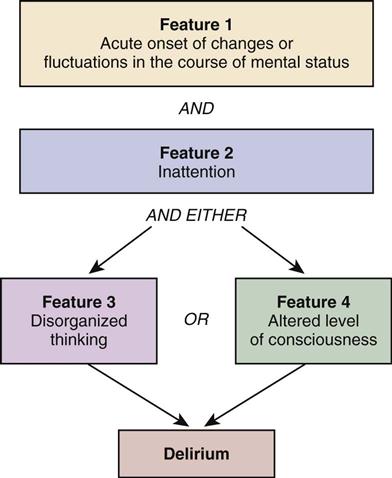

Specific scoring instruments are available to assess delirium, and two have been validated for use with mechanically ventilated critical care patients.24 They are the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) (Figure 9-2),25–27 and the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC).28,29 Both instruments are used in tandem with the RASS to exclude patients in coma, and identify hyperactive delirium (see Table 9-1). Both instruments provide a structured format to evaluate delirium for verbal patients and for nonverbal and mechanically ventilated patients.

Pharmacological Management of Agitation and Delirium

Selecting medications that provide sedation but avoid withdrawal-associated agitation is a priority. The neuroleptic drug haloperidol (Haldol) is administered to treat hyperactive delirium.30 This antipsychotic agent stabilizes cerebral function by blocking dopamine-mediated neurotransmission at the cerebral synapses and in the basal ganglia. Electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring is recommended, because haloperidol prolongs the QTc-interval, increasing the risk of ventricular dysrhythmias.

Nonpharmacological Interventions to Prevent Delirium

Hyperactive delirium is frequently associated with critical illness.1 The nonpharmacological strategies used to prevent agitation and delirium are similar to those used as adjuncts to minimize pain.1 These methods include back massage, music therapy, noise reduction, decreasing lights at night to promote sleep, clustering nursing care interventions to provide some uninterrupted rest, and speaking in a calm and gentle voice. Some preexisting conditions increase the likelihood that a patient will experience delirium, including dementia, alcohol use disorder, and prior sedative/opiate dependence.

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome and Delirium Tremens

Critically ill patients who are alcohol-dependent, and were drinking prior to hospital admission, are at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS).31 AWS is associated with an increased risk of delirium, hallucinations, seizures, increased need for mechanical ventilation, and death. When hyperactive agitated delirium is caused by alcohol withdrawal, it is termed delirium tremens, often called DTs.31 Following hospital admission, as the alcohol-dependent patient’s blood-alcohol concentration (BAC) falls, about 50% of patients will have AWS-related symptoms.32 Fewer than 5% will experience severe complications such as delirium tremens or a seizure.31,32 Screening tools to identify alcohol dependence, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) shown in Table 25-1 in the Trauma chapter (25), are very helpful. Management of alcohol withdrawal involves close monitoring of AWS-related agitation and administration of IV benzodiazepines, generally diazepam (Valium) or lorazepam (Ativan). Diazepam has the advantage of a longer half-life and high lipid solubility.31 Lipid-soluble medications quickly cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the central nervous system to rapidly produce a sedative effect.31,33 Benzodiazepines should be administered in response to increased signs of agitation associated with DTs, with dosage guided by a clinical protocol. This is described as an AWS symptom-triggered approach.31 The severity of alcohol withdrawal can be assessed with a scale such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale (revised) (CIWA-Ar).31,33 Multivitamins, including thiamine (vitamin B1), are administered prophylactically to prevent additional neurological sequelae.31–34 Delirium related to alcohol withdrawal is pharmacologically managed very differently from delirium from other causes. Long-acting benzodiazepines are the drugs of choice in AWS.31 In contrast, benzodiazepines are contraindicated for treatment of delirium from non-alcohol-related causes.35

Collaborative Management

Collaborative management of anxiety, agitation, sedation, and delirium is a responsibility shared by all members of the health care team, as seen in the Evidence-Based Collaborative Practice box on Sedation in the Critically Ill). Recognition of the problem is the first step toward a solution to establish a more effective standard of patient care in sedation, analgesia, and delirium management.