Chapter 81 Sedation, analgesia and muscle relaxation in the intensive care unit

Despite the widespread use of sedative and analgesic agents in the intensive care unit (ICU), the goals of sedation and analgesia are not well-established. Indications for the use of sedative agents include:

SEDATION

Sedative agents are used in an attempt to:

LEVEL OF SEDATION

The level of sedation required will vary, depending on the indication, e.g. heavy sedation may be necessary during the control of status epilepticus, while a much lower level of sedation will be required to tolerate endotracheal intubation. Modern modes of mechanical ventilation do not demand heavy sedation in order to be comfortably tolerated. The aim of sedation should be clear to the treating team and the desired level of sedation should be determined and documented. Once sedation is instituted, the level of sedation should be regularly assessed. Protocol-based therapy reduces drug costs and enhances the quality of sedation and analgesia.2 Failure to follow such a protocolised approach can result in significant problems, such as:3

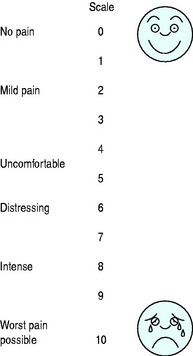

Level of sedation may be assessed by means of a number of measurement tools including:

| Level | Response |

|---|---|

| Awake levels | |

| 1 | Patient anxious and agitated or restless or both |

| 2 | Patient cooperative, orientated and tranquil |

| 3 | Patient responds to commands only |

| Asleep levels | |

| 4 | Brisk response to a light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus |

| 5 | Sluggish response to a light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus |

| 6 | No response to a light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus |

Level of sedation may also be assessed by monitoring physiological parameters for signs of distress. A ‘drug free’ period every day, when sedative agents are completely withdrawn, is an excellent means of assessing level of sedation4 – by taking note of the time for a patient to either wake up or rise to a predetermined level on the Ramsay scale.

SEDATIVE AGENTS USED IN THE ICU

BENZODIAZEPINES

Dosage of these agents is by titration and may vary widely depending on factors such as:

INTRAVENOUS ANAESTHETIC AGENTS

Propofol

The i.v. anaesthetic agent propofol (2,6-di-isopropylphenol) is frequently used for sedation in the ICU. It is fast acting, very effective and has a rapid offset of action (due to its rapid metabolism to inactive metabolites in the liver). These features make it very suitable for use in patients requiring short-term sedation or for anaesthesia for procedures in the ICU. Although propofol has been shown to reduce time on mechanical ventilation compared with BZA (specifically midazolam) sedation, it has not been shown to reduce time in the ICU.5,6 Caution is required in hypovolaemic patients or those with impaired myocardial function, as severe hypotension may result. Doses for ICU sedation are generally much lower than the 6–12 mg/kg per hour required for anaesthesia. The diluent in which propofol is delivered is lipid-rich and may have to be taken into account as a source of nutrition and indeed cause of hyperlipidaemia, depending on dosage and duration of therapy. Disodium edetate, present in the propofol solution, does not appear to be harmful in patients receiving long-term infusions of propofol.7

There has been some recent concern about the so-called ‘propofol infusion syndrome’ where particularly paediatric patients, but also adults, have developed severe heart failure (preceded by metabolic acidaemia, fatty infiltration of the liver and striated muscle damage) after prolonged high-dose infusions of propofol.8 Caution should therefore be exercised when using propofol for prolonged periods.

VOLATILE ANAESTHETIC AGENTS

The widespread use of volatile anaesthetic agents for sedation in the ICU has been limited by:

Volatile agents are useful for short periods of anaesthesia during invasive procedures in the ICU. They may be used, with effect, for longer periods for sedation (up to a few days) in acute severe asthma, due to their bronchodilatory action. Short-term administrations of Entonox (50% nitrous oxide in oxygen) are still useful for analgesia and sedation during painful procedures (e.g. removal of intercostal catheters). This may be given by demand valve (controlled by the patient) or be administered by the medical staff.

ANALGESIA

Pain management is an important priority in the care of critically ill patients.

When drug therapy is required to alleviate pain, the following groups of drugs are commonly used:

OPIOIDS

Opioids remain the mainstay of analgesia in the ICU. This group of drugs encompasses:

The effect of analgesia in the clinical setting is judged by:

In the critically ill, the use of opioids may be complicated by:

PHARMACOKINETIC CONSIDERATIONS

The pharmacokinetics of analgesics and sedatives can be affected by such factors as:

Use of simple analgesics or NSAIDs to treat pain will reduce the amount of opioid required.

SIMPLE ANALGESICS

Paracetamol and other simple analgesics (e.g. salicylates) are particularly effective for:

NSAIDs

The newer cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) specific inhibitors, such as valdecoxib and its injectable precursor parecoxib, have a much lower side-effect profile than traditional NSAIDs. These drugs should be used only for short periods, due to recent evidence regarding increased cardiovascular morbidity associated with long-term use of the COX-2 inhibitors.11

LOCAL ANAESTHETICS – REGIONAL ANAESTHESIA/ANALGESIA

The use of local anaesthetic techniques in the critically ill patient is limited by:

Within the context above, the following blocks may be useful in individual patients:

MUSCLE RELAXANTS

CHOICE OF MUSCLE RELAXANT

Depolarising muscle relaxants are to be used with caution in the ICU patient who has:

1 Rhoney DH, Parker DJ. Use of sedative and analgesic agents in neurotrauma patients: effects on cerebral physiology. Neurol Res. 2001;23:237-259.

2 MacLaren R, Plamondon JM, Ramsay KB, et al. A prospective evaluation of empiric versus protocol-based sedation and analgesia. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:662-672.

3 Wiener-Kronish JP. Problems with sedation and analgesia in the ICU. Pulm Pers. 2001;18:1-3.

4 Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, et al. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1471-1477.

5 Hall RI, Sandham D, Cardinal P, et al. Propofol vs midazolam for ICU sedation: a Canadian multicenter randomized trial. Chest. 2001;119:1151-1159.

6 Walder B, Elia N, Henzi I, et al. A lack of evidence of superiority of propofol versus midazolam for sedation in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a qualitative and quantitative systemic review. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:975-983.

7 Abraham E, Papadakos PJ, Tharratt RS, et al. Effects of propofol containing EDTA on mineral metabolism in medical patients with pulmonary dysfunction. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(Suppl 4):S422-S432.

8 Bray RJ. The propofol infusion syndrome in infants and children: can we predict the risk? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2002;15:339-342.

9 Nasraway SA. Use of sedative medications in the intensive care unit. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22:165-174.

10 Aissaoui Y, Zeggwahg AA, Zekraoui A, et al. Validation of a behavioural pain scale in critically ill, sedated and mechanically ventilated patients. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1470-1476.

11 Lee YH, Ji JD, Song GG. Adjusted indirect comparison of celecoxib versus rofecoxib on cardiovascular risk. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27:477-482.