CHAPTER 7 Screening and Assessment Tools

7A. Measurement and Psychometric Considerations

In a general pediatric population, practitioners can expect 8% of their patients to experience significant developmental or behavioral problems between the ages of 24 and 72 months, this rate increasing to 12% to 25% during the first 18 years.1,2 Therefore, consideration and interpretation of tests and rating scales are part of the clinician’s day-to-day experience, regardless of whether the choice is made to administer evaluations or review test or rating scale data obtained by other professionals.

This chapter is an introduction to the section on assessment and tools. It contains topics such as: discussion of descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, median, mode), distributions of scores and standard deviations, transformation of scores (percentiles, z-scores, T-scores), psychometric concerns (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values), test characteristics (reliability, validity), and age and grade equivalents. Many of these topics are also elaborated in greater detail in subsequent chapters of this text. A more thorough discussion of psychological assessment methods can be found in Sattler’s text.3

Developmental and psychological evaluations usually include measurement of a child’s development, behavior, cognitive abilities, or levels of achievement. Comprehensive child assessments involve a multistage process that incorporates planning, collecting data, evaluating results, formulating hypotheses, developing recommendations, and conducting follow-up evaluations.3 Test data provide samples of behavior, with scores representing measurements of inferred attributes or skills. These scores are relative and not absolute measures, and rating scales and test instruments are typically used to compare a child to a standardized, reference group of other children. Approximately 5% of the general population obtains scores that fall outside the range of “normal.” However, the range of normal is descriptive, not diagnostic: it describes problem-free individuals, but does not provide a diagnosis for them.3 No test is without error, and scores may fall outside the range of normal simply as a result of chance variation or issues such as refusal to take a test. Three major sources of variation that may affect test data include characteristics of a given test, the range of variation among normal children, and the range of variation among children who have compromised functioning.

In general, regardless of whether a measurement tool is designed to be used as an assessment or a screening instrument, the normative sample on which the test is based is critical. Test norms that are to be applied nationally should be representative of the general population. Demographics must proportionately reflect characteristics of the population as a whole, taking into account factors such as region (e.g., West, Midwest, South, Northeast), ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and urban/rural setting. If a test is developed with a nonrepresentative population, characteristics of that specific sample may bias norms and preclude appropriate application to other populations. Adequate numbers of children need to be included at each age across the age span evaluated by a given test so as to enhance stability of test scores. Equal numbers of boys and girls should be included. Clinical groups should also be included for comparison purposes. Convenience samples, or those obtained from one geographic location are not appropriate for development of test norms.

Tests generally need to be reduced and refined by eliminating psychometrically poor items during the development phase. Conventional item analysis is one such approach and involves evaluation of an item difficulty statistic (percentage of correct responses) and patterns of responses. The use of item discrimination indexes (item-total correlations) and item validity (discrimination between normative and special groups, by T-tests or chi square analyses) is routine. More recent tests such as the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development—Third Edition (BSID-III)4 or the Stanford-Binet V5 employ inferential norming6 or item response theory.7 Item response theory analyses involve difficulty calibrations for dichotomous items and step differences for polychotomous items, the goal being a smooth progression of difficulty across each subtest (e.g., as in the Rasch probabilistic model8). Item bias and fairness analysis are also components; this procedure is called differential item functioning.9 See Roid5 or Bayley4 for a more detailed description of these procedures.

STANDARDIZED ASSESSMENTS

Standardized normreferenced assessments (SNRAs) are the tests most typically administered to infants, children, and adolescents. The most parsimonious definition of SNRAs is that they compare an individual child’s performance on a set of tasks presented in a specific manner with the performance of children in a reference group. This comparison is typically made on some standard metric or scale (e.g., scaled score).10 Although there may be some allowance for flexibility in rate and order of administration procedures (particularly in the case of infants), administration rules are precisely defined. The basis for comparison of scores is that tasks are presented in the same manner across testings, and there are existing data that represent how similar children have performed on these tasks. However, if this format is modified, additional variability is added, precluding accurate comparison of the child’s data and those of the normative group.

Use of SNRAs is not universally endorsed, particularly with regard to infant assessment, because of concerns regarding one-time testing in an unfamiliar environment, different objectives for testing, and linkage to intervention, instead of diagnosis. Therefore, emphasis is placed on alternative assessments that rely on criterion-referenced and curriculum-based approaches. In actuality, curriculum-based assessment is a type of a criterion-referenced tool. These assessments can help to answer the second question posed previously and could also better delineate the child’s strengths. Both provide an absolute criterion against which a child’s performance can be evaluated. In criterion-referenced tests, the score a child obtains on a measurement of a specific area of development reflects the proportion of skills the child has mastered in that particular area (e.g., colors, numbers, letters, shapes). For example, in the Bracken Basic Concepts Scale—Revised,11 in addition to normreferenced scores, examiners can also determine the percentage of mastery of skills in the six areas included in the School Readiness Composite. More specifically, in the colors subtest, the child is asked to point to colors named by the examiner. This raw score can be converted to a percentage of mastery, which is computed regardless of age. Similarly, other skills such as knowledge of numbers and counting or letters can be gauged. In curriculum-based evaluations, the emphasis is on specific objectives that are to be achieved, the potential goal being intervention planning.12,13 The Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System for Infants and Children14 and the Carolina Curricula for Infants and Toddlers with Special Needs15 are examples of curriculum-based assessments. Therefore, SNRAs, criterion-referenced tests, and curriculum-based tests each have a role, depending on the intended purpose of the evaluation.

PRIMER OF TERMINOLOGY USED TO DETECT DYSFUNCTION

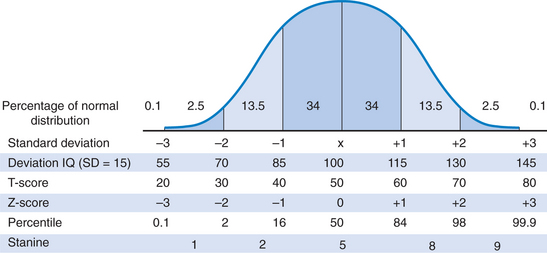

The normal range is a statistically defined range of developmental characteristics or test scores measured by a specific method. Figure 7A-1 depicts a normal distribution or bell-shaped curve. This concept is critical in the development of test norms and provides a basis for the following discussion.

Descriptive Statistics

The mean (M) is a measure of central tendency and is the average score in a distribution. Because it can be affected by variations caused by extreme scores, the mean can be misleading in scores obtained from a highly variable sample. In Figure 7A-1, the mean score is 100.

The median is defined as the middle score that divides a distribution in half when all the scores have been arranged in order of increasing magnitude. It is the point above and below which 50% of the scores fall. This measure is not affected by extreme scores and therefore is useful in a highly variable sample. In the case of an even number of data points in a distribution, the median is considered to be halfway between two middle scores. Noteworthy is the fact that in the normal distribution depicted in Figure 7A-1, the mean, mode, and median are equal (all scores = 100), and the distribution is unimodal.

The range is a measure of dispersion that reflects the difference between the lowest and highest scores in a distribution (highest score − the lowest score +1). However, the range does not provide information about data found between two extreme values in the test distribution, and it can be misleading when the clinician is dealing with skewed data. In this situation, the interquartile range may be more useful: The distribution of scores is divided into four equal parts, and the difference between the score that marks the 75th percentile (third quartile) and the score that marks the 25th percentile (first quartile) is the interquartile range.16

The standard deviation (SD) is a measure of variability that indicates the extent to which scores deviate from the mean. The standard deviation is the average of individual deviations from the mean in a specified distribution of test scores. The greater the standard deviation, the more variability is found in test scores. In Figure 7A-1, SD = 15 (the typical standard deviation in normreferenced tests). In a normal distribution, the scores of 68% of the children taking a test will fall between +1 and −1 standard deviation (square root of the variance). In general, most intelligence and developmental tests that employ deviation quotients have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Scaled scores, such as those found in the Wechsler tests, have a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3 (7 to 13 being the average range). If a child’s score falls less than 2 standard deviations below average on an intelligence test (i.e., IQ < 70), he or she may be considered to have a cognitive-adaptive disability (if adaptive behaviors are also impaired).

Skewness refers to test scores that are not normally distributed. If, for example, an IQ test is administered to an indigent population, the likelihood that more children will score below average is increased. This is a positively skewed distribution (the tail of the distribution approaches high or positive scores, i.e. the right portion of the x-axis). Here, the mode is a lower score than the median, which, in turn is lower than the mean. Probabilities based on a normal distribution will yield an underestimate of the scores at the lower end and an overestimate of the scores at the higher end. Conversely, if the test is administered to children of high socioeconomic status, the distribution might be negatively skewed, which means that most children will do well (the tail of the distribution trails toward lower scores or the left portion of the x-axis). In negatively skewed distributions, the value of the median < mean < mode scores at the lower end will be overestimated, and those at the upper end will be underestimated. Skewness has significant ramifications in interpretation of test scores. In fact, the meaning of a score in a distribution depends on the mean, standard deviation, and the shape of the distribution.

Transformations of Raw Scores

LINEAR TRANSFORMATIONS

Linear transformations provide information regarding a child’s standing in comparison to group means. The z-score is a standard score (standardization being the process of converting each raw score in a distribution into a z-score: raw score − the mean of the distribution, divided by the standard deviation of the distribution) that corresponds to a standard deviation; that is, a z-score of +1 is 1 standard deviation above average and a z-score of −1 is 1 standard deviation below average. The mean equals a z-score of 0; therefore scores between z-scores of −1 and +1 are in the average range. Stated differently, if a child receives a z-score of +1, he or she obtained a score higher than those of 84% of the population (see Fig. 7A-1).

AREA TRANSFORMATIONS

The stanine is short for standard nine, and this metric divides a distribution into nine parts. The mean = 5, and the SD = 2, with the third to seventh stanine being considered the average range. Approximately 20% of children score in the fifth stanine, 17% each in the fourth and sixth stanines, and 12% each in the third and seventh stanines (78% in total). Stanines are frequently encountered with group administered tests such as the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills, the Metropolitan Achievement Tests, or the Stanford Achievement Tests. The interrelatedness of these scores is depicted in Figure 7A-1.

PSYCHOMETRIC CONCERNS

Sensitivity and Specificity

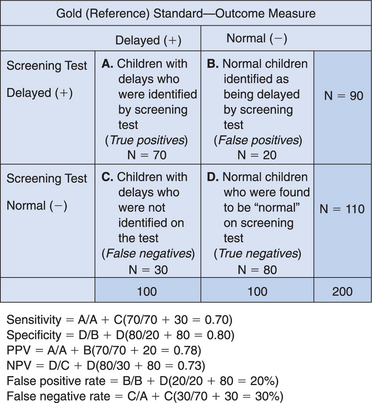

Frequently, interpretation of test results must take into account how well the instrument performs with set cutoff scores. Sensitivity is a measure of the proportion of children with a specific problem who are positively identified by a test, with a specific cutoff score. Children who have a disorder but are not identified by the test are considered to have false-negative scores. In developmental/behavioral pediatrics, the “gold standard” (criterion used to determine the presence of a given problem) often is not definitive but rather is a reference standard. Comparison with an imperfect “gold standard” may lead to erroneous conclusions that a screening test is inaccurate. As a result, sensitivity may be better conceptualized as copositivity. Desired sensitivity rates are 70% to 80%, and sensitivity is the true positive rate of a test.

Cutoff scores can be adjusted to enhance sensitivity. By making criteria more inclusive, fewer children with true abnormalities will be missed; however, a more restrictive cutoff will also increase the probability of false-positive findings (overidentifying “normal” children as being abnormal). Conversely, if the cutoff score is made more exclusive to enhance specificity, the number of normal children inaccurately identified as abnormal is decreased, but some of those who are truly abnormal will be erroneously called normal (false-negative findings). Sensitivity and specificity are described in Figure 7A-2.

Frequency of a Disorder/Problem

Base rate is the naturally occurring rate of a given disorder. For example, the base rate of learning disabilities would be much higher in children referred to a learning and attention disorders clinic than in the general population. If a screening instrument were used to detect learning disabilities for this group, sensitivity and specificity values would differ from those found in the general pediatric population. For example, in the follow-up of low-birth-weight infants, the base rate for major handicaps (moderate to severe mental retardation; cerebral palsy; epilepsy; deafness or blindness) is 15%; therefore, in 85% of this population, the findings would be true negative. Low base rates increase the possibility of false-positive results. High base rates do not leave much room for improvement in terms of locating true-positive scores and result in an increase in false-negative findings. Tests can be most helpful in decision making when the base rate is in the vicinity of 0.50. Therefore, particularly in the case of screening, the relatively low base rates of developmental problems in very young children may increase the probability of false positive findings. However, in such situations, this scenario is more desirable than the converse: false negative findings.

Relative risk provides an alternative strategy for evaluating test accuracy.17,18 This approach involves use of the likelihood ratio, which indicates the increased probability that the child will display a developmental problem, if the results of an earlier screening test were abnormal or suspect. This approach recognizes that not all children at early risk will later manifest a developmental problem, but there is a greater likelihood that they will. If a problem or disorder is rare, relative risk and odds ratios are nearly equal.

Test Characteristics

RELIABILITY

Reliability is affected by test length (longer tests are more reliable), test-retest interval (longer interval lessens reliability), variability of scores (greater variance increases reliability estimate), guessing (increased guessing decreases reliability), variations in test situation, and practice effects.3

VALIDITY

Content validity determines whether the items in the test are representative of the domain the test purports to measure: that is, whether the test does cover the material it is supposed to cover. Construct validity concerns whether the test measures a particular psychological construct or trait (e.g., intelligence). Criterion-related validity involves the current relationship between test scores and some criterion, such as results of another test. Criterion-related validity can be concurrent (convergent) or predictive. In both instances, the results of a test under consideration are compared to an established reference standard to determine whether findings are comparable. In concurrent validity, the two tests (e.g., a screen such as the Bayley Infant Neurodevelopmental Screener and a “reference standard” such as the BSID-II) are administered at the same time, and the results are correlated. With predictive validity, a screening test might be given at one time, followed by administration of the reference standard at a later date (e.g., the BSID-II is given to children aged 36 months, and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence—III at age 4½ years). Discriminant validity shows how well a screening test detects a specific type of problem. For example, autism might be the condition of concern, and a screening test such as the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) is used to distinguish children with this disorder from those with mental retardation without autism. Face validity involves whether the test appears to measure what it is supposed to measure. Test-related factors (examiner-examinee rapport, handicaps, motivation), criterion-related factors, or intervening events could affect validity.

With regard to the interrelatedness among reliability and validity, reliability essentially sets the upper limit of a test’s validity, and reliability is a necessary but not sufficient condition for valid measurement. A specific test can be reliable, but it may be invalid when used to evaluate a function that it was not designed to measure. However, if a test is not reliable, it cannot be valid. Stated differently, all valid tests are reliable, unreliable tests are not valid, and reliable tests may or may not be valid.19

Age and Grade Equivalents

The IQ/DQ ratio (developmental quotient) is computed as mental age (obtained by the use of a test score) ÷ the child’s chronologic age and then multiplied by 100. Although developmental age refers to a level of functioning, DQ reflects the rate of development.19 IQ/DQ ratio scores are not comparable at different age levels because the standard deviation (variance) of the ratio does not remain constant. As a result, interpretation is difficult, and these scores generally are not used very much in contemporary standardized testing. Instead, the deviation IQ/DQ is employed. The deviation IQ is a method of estimation that allows comparability of scores across ages and is used with most major psychological and developmental test instruments. The deviation IQ/DQ is norm referenced and normally distributed, with the same standard deviation; typically, M = 100 and SD = 15. Therefore, a deviation IQ of 85 obtained at age 6 should have the same meaning as a score of 85 obtained at age 9.

A final concern is the Flynn effect,20 in which test norms increase approximately 0.3 to 0.5 points per year, which is equivalent to a 3- to 5-point increment per decade. This finding has ramifications in comparisons of scores obtained on earlier versions of tests to more contemporary scores (e.g., WISC-Revised to the WISC—Third Edition or WISC-IV; BSID to BSID-II; Stanford-Binet form LM to the 5th edition). Caution is warranted when the practitioner attributes a decline in scores to a loss of cognitive ability, because in actuality this decline may be attributable to the fact that a newer test has mean scores that are considerably lower than those of an earlier version of the test (e.g., 5-8 points).20 This issue would also have ramifications for children whose IQ score on an older version of a test is in the low 70s but decreases to below the cutoff for mild mental retardation on a newer version.

Although some practitioners may administer tests, all have occasion to respond to inquiries from parents about their child’s test performance or diagnosis derived from testing. The physician’s role includes explaining test results to parents, acknowledging parental concerns and advocating for the child, providing additional evaluation, or referring to other professionals.21

1 Costello EJ, Edelbrock C, Costello AJ, et al. Psychopathology in pediatric primary care: The new hidden morbidity. Pediatrics. 1988;82:415-424.

2 Lavigne JV, Binns HJ, Christoffel KK, et al. Behavioral and emotional problems among preschool children in pediatric primary care: Prevalence and pediatricians’ recognition. Pediatrics. 1993;91:649-657.

3 Sattler JM. Assessment of Children, 4th ed. San Diego: Jerome M. Sattler, 2001.

4 Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition: Technical Manual. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp, 2005.

5 Roid GH. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales for Early Childhood, Fifth Edition: Manual. Itasca, IL: Riverside, 2005.

6 Wilkins C, Rolfhus E, Weiss L, et al: A Simulation Study Comparing Inferential and Traditional Norming with Small Sample Sizes. Paper presented at annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, Canada, 2005.

7 Wright BD, Linacre JM. WINSTEPS: Rasch Analysis for All Two-Facet Models. Chicago: MESA, 1999.

8 Rasch G. Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

9 Dorans NJ, Holland PW. DIF detection and description: Mantel-Haenszel and standardization. In: Holland PW, Wainer H, editors. Differential Item Functioning. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993:35-66.

10 Gyurke JS, Aylward GP. Issues in the use of normreferenced assessments with at-risk infants. Child Youth Fam Q. 1992;15:6-8.

11 Bracken BA. Bracken Basic Concepts Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, 1998.

12 Greenspan SI, Meisels SJ. Toward a new vision for the developmental assessment of infants and young children. In: Meisels SJ, Fenichel E, editors. New Visions for the Developmental Assessment of Infants and Young Children. Washington, DC: Zero to Three: National Center for Infants Toddlers and Families; 1996:11-26.

13 Meisels S. Charting the continuum of assessment and intervention. In: Meisels SJ, Fenichel E, editors. New Visions for the Developmental Assessment of Infants and Young Children. Washington, DC: Zero to Three: National Center for Infants Toddlers and Families; 1996:27-52.

14 Bricker D. Assessment, Evaluation and Programming System for Infants and Children, Volume 1: AEPS Measurement for Birth to Three Years. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, 1993.

15 Johnson-Martin N, Jens K, Attermeir S, et al. The Carolina Curriculum, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, 1991.

16 Urdan T. Statistics in Plain English. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2001.

17 Frankenburg WK, Chen J, Thornton SM. Common pitfalls in the evaluation of developmental screening tests. J Pediatr. 1988;113:1110-1113.

18 Frankenburg WK. Preventing developmental delays: Is developmental screening sufficient? Pediatrics. 1994;93:586-593.

19 Salvia J, Ysseldyke JE. Assessment, 8th ed. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2001.

20 Flynn JR. Searching for justice. The discovery of IQ gains over time. Am Psychol. 1999;54:5-20.

21 Aylward GP. Practitioner’s Guide to Developmental and Psychological Testing. New York: Plenum Medical, 1994.

7B. Surveillance and Screening for Development and Behavior

More than three decades have elapsed since the identification of developmental, behavior, and psychosocial problems as the so-called “new morbidity” of pediatric practice.1 During the ensuing years, profound societal change, with public policy mandates for deinstitutionalization and mainstreaming, has further influenced the composition of pediatric practice. Studies have documented the high prevalence of developmental and behavioral issues within the practice setting, including disorders of high prevalence and lower severity such as specific learning disability, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and speech and language impairment, as well as problems of higher severity and lower prevalence such as mental retardation, autism, cerebral palsy, hearing impairment, and serious emotional disturbance.2

The critical influence of the early childhood years on later school success and the well-documented benefits of early intervention provide a strong rational for the early detection of children at risk for adverse developmental and behavioral outcomes. Neurobiological, behavioral, and social science research findings from the 1990s, the so-called decade of the brain, have emphasized the importance of experience on early brain development and on subsequent development and behavior and the extent to which the less differentiated brain of the younger child is particularly amenable to intervention.3

BACKGROUND

Early identification and intervention affords the opportunity to avert the inevitable secondary problems with loss of self-esteem and self-confidence that result from years of struggle with developmental dysfunction. Federal legislation, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004, and related state legislation mandate early detection and intervention for children with developmental and behavioral disabilities. Surveys indicate that parents have strong interest in promoting children’s optimal development.4,5

Perhaps the most compelling rationale for early detection is the effectiveness of early intervention. Researchers have documented the benefits of early intervention in children with mental retardation and physical handicaps, particularly when improved family functioning is a measured outcome.6 More recently, the benefits of early intervention for children at environmental risk has also been demonstrated. For example, enrollment and participation of disadvantaged children in Head Start programs contribute to a decreased likelihood of grade repetition, less need for special education services, and fewer school dropouts.7 Detection is also supported by the clearer delineation of adverse influences on children’s development. For example, the effect of such diverse factors as low-level lead exposure and adverse parent-infant interaction on child development has implications for early identification.

By virtue of their access to young children and their families, child health providers are particularly well positioned to participate in early identification of children at risk for adverse outcomes through ongoing monitoring of development and behavior. Clinicians’ knowledge of medical and genetic factors also facilitates early identification of conditions associated with developmental problems. Furthermore, through their relationships with children and their families, pediatricians and other child health providers are familiar with the social and familial factors that place children at environmental risk. Professional guidelines emphasize the importance of early detection by child health providers. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Children with Disabilities; Medicaid’s Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program; and Bright Futures (guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau) all encourage the effective monitoring of children’s development and behavior and the prompt identification of children at risk for adverse outcomes.8,9 The emphasis on the primary care practice as a comprehensive medical home for all children also supports the office as the ideal medical setting for developmental and behavioral monitoring.10

Despite this strong rationale, results of surveys of parents and child health providers demonstrate that current practices widely vary and suggest the need to strengthen developmental monitoring and early detection. Only about half of parents of children aged between 10 and 35 months recall their children’s ever having received structured developmental assessments from their child health providers.11 Parents also report gaps in the discussion of development and related issues with pediatric providers.12 Most pediatricians employ informal, nonvalidated approaches to developmental screening and assessment. The majority of pediatricians do not incorporate within their practice such tools as those recommended by Bright Futures to aid in early detection.13

Not surprisingly, the early detection of children at risk for adverse developmental and behavioral outcomes has proved elusive. Fewer than 30% of children with such disabilities as mental retardation, speech and language impairments, learning disabilities, and serious emotional/behavioral disturbances are identified before school entry.13 This lack of detection precludes the opportunity and benefits of timely, early intervention. Although nearly half of parents have some concerns for their child’s development or behavior, such concerns are infrequently elicited by child health providers.14

DEVELOPMENTAL SURVEILLANCE

Currently, child health providers employ a variety of techniques to monitor children’s development and behavior. History taking during a health supervision visit typically includes a review of age-appropriate developmental milestones. Unfortunately, recall of such milestones is notoriously unreliable and typically reflects parents’ prior conceptions of children’s development.15 Although the accuracy in determining the age of performing certain tasks is certainly improved by the use of diaries and records, the wide range of normal acquisition for such milestones limits their value in assessing children’s developmental progress. Child health providers may also question parents as to their predictions for their child’s development. Predictions (typically elicited with questions such as “when your child becomes an adult, do you think he or she will be above average, average, or below average?”) are also unhelpful in developmental monitoring, because parents are likely to expect average functioning for children with delays and predict overachievement for children developing at an average pace, a phenomenon dubbed the presidential syndrome.15

During the physical examination, child health providers may interact with children by using an informal collection of age-appropriate tasks. The lack of a standardized approach to measuring developmental progress makes interpretation of children’s performance on such tasks difficult. The reliance of child health providers on “clinical judgment,” based on subjective impressions during the performance of the history and physical examination, are also fraught with hazard. Such impressions are unduly influenced by the extent to which a child is verbal and sociable in a setting that may be frightening, an effect likely to restrict affect and deter spontaneous demonstrations of pragmatic language skills. Studies have documented the poor correlation between provider’s subjective impressions of children’s development and the results of formal assessments. Clinical judgment identifies fewer than 30% of children with developmental disabilities.15 The reliance on subjective impressions undoubtedly contributes to the late identification of children with such developmental issues as mild mental retardation.

According to research findings and expert opinion, surveillance and screening constitute the optimal approach to developmental monitoring.16 As originally described by British investigators, surveillance encompasses all activities relating to the detection of developmental problems and the promotion of development through anticipatory guidance during primary care.17 Developmental surveillance is a flexible, longitudinal, continuous process in which knowledgeable professionals perform skilled observations during child health care.17 Although surveillance is most typically performed during health supervision visits, clinicians may perform opportunistic surveillance during sick visits by exploring the child’s understanding of illness and treatment.18a

The emphasis of developmental surveillance is on skillfully observing children and identifying parental concerns. Components include eliciting and attending to parents’ opinions and concerns, obtaining a relevant developmental history, skillfully and accurately observing children’s development and parent-child interaction, and sharing opinions and soliciting input from other professionals (e.g., visiting nurse, child care provider, preschool and school teacher), particularly when concerns arise. Developmental history should include an exploration of both risk and protective factors, including environmental, genetic, biological, social, and demographic influences, and observations of the child should include a careful physical and neurological examination. Surveillance stresses the importance of viewing the child within the context of overall well-being and circumstance.17

The most critical component of surveillance is eliciting and attending to parents’ opinions and concerns. Research has elucidated the value of information available from parents. Although there are several ways to obtain quality information, research on parents’ concerns is voluminous. Concerns are particularly important indicators of developmental problems, particularly for speech and language function, fine motor skills, and general functioning (e.g., “He’s just slow”).15,18 Although concerns about self-help skills, gross motor skills, and behavior are less sensitive indicators of developmental functioning, such opinions should serve as clinical “red flags,” mandating closer clinical assessment and developmental promotion.15,18 The manner in which parental concerns are elicited is important. Asking parents whether they have worries about their children’s development is unlikely to be useful, because they may be reluctant to acknowledge fears and interpret “development” as merely reflecting physical growth. In contrast, asking parents whether they have any concerns about the way their child is behaving, learning, and developing, followed by more specific inquiry about functioning in specific developmental domains, is more likely to yield valid and clinically useful responses.18,19 Clinicians must be mindful of the complex relationship between concerns and disability (some concerns are predictors of developmental status only at certain ages), the critical importance of eliciting concerns rather than relying on parents to volunteer, and the value of an evidence-based approach to interpreting concerns.18,21

Parents’ estimations are also accurate indicators of developmental status. For example, a study conducted in primary care demonstrated the extent to which parents’ estimates of cognitive, motor, self-help, and academic skills correlate with findings on developmental assessments.22 Parental responses to the question, “Compared with other children, how old would you say your child now acts?” are important indicators of developmental delay, although such questions are more challenging for parents than elicitations of concerns.22

Parents’ opinions and concerns must be considered within the context of cultural influences. Parents’ appraisals and descriptions are influenced by expectations for children’s normal development, and such expectations vary among different ethnic groups. For example, in a study of Latino (primarily Puerto Rican), African American, and European American mothers, Puerto Rican mothers expected personal and social milestones to be normally achieved at a later age than did the other groups, whereas first steps and toilet training were expected at an older age by European American mothers.23 Such differences were often explained by underlying cultural beliefs, values, and childrearing practices. For example, the older age for achievement of self-help skills is consistent with the Puerto Rican concept of familismo and its emphasis on caring for children.

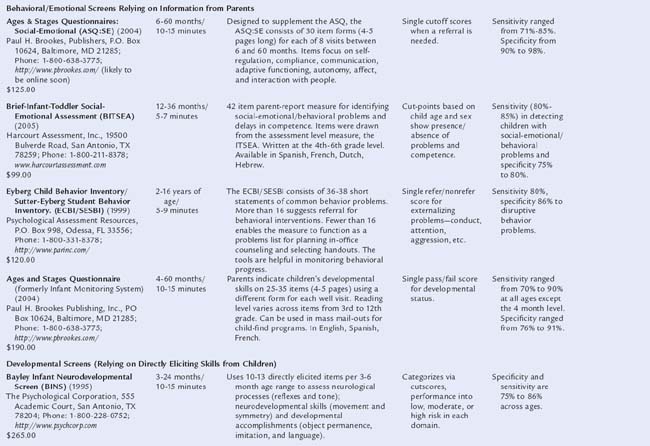

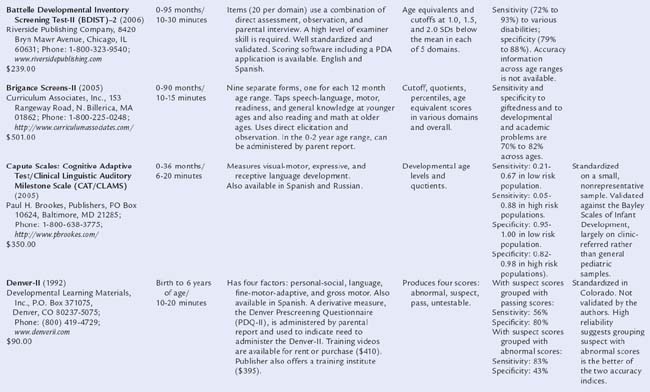

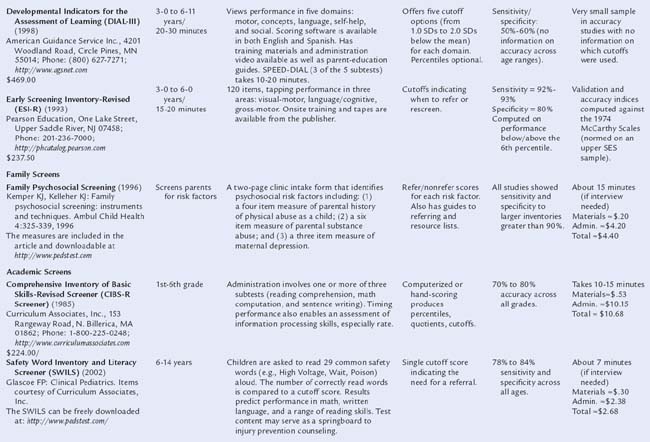

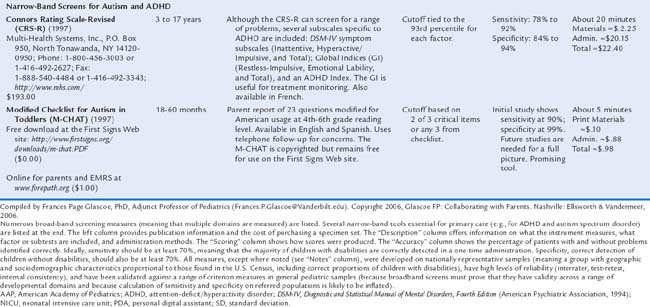

USE OF SCREENING TOOLS

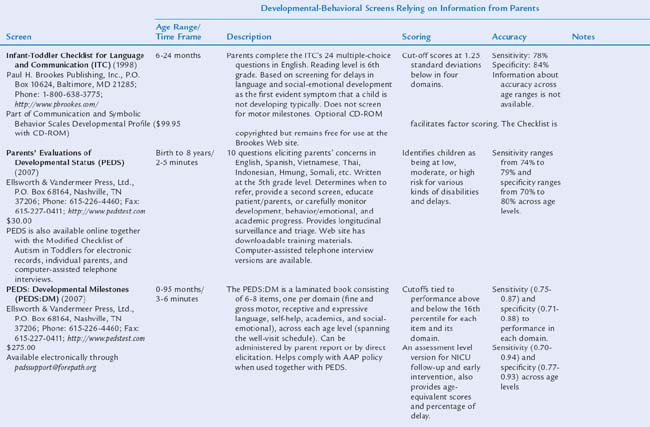

Table 7B-1 includes descriptions of screening tools that are highly accurate: that is, based on nationally representative samples, fulfilling psychometric criteria (see Chapter 7A), and having both sensitivity and specificity of at least 70% to 80%. Two types of tools are presented: those relying on information from parents and those requiring direct elicitation of children’s skills. The latter are useful in practices with staff (e.g., nurses, pediatric nurse practitioners) who have the time and skill to administer relatively detailed screens. Such measures are also useful in early intervention programs. Information is included on purchasing, cost, time to administer, scores produced, and age ranges of the children tested.

COMBINING SCREENING AND SURVEILLANCE

We now present an algorithm for combining surveillance and screening into an effective, evidence-based process for detecting and addressing developmental and behavioral issues. The American Academy of Pediatrics recently revised its policy statement on early detection.8 We include the elements of the statement, as follows.

SYSTEMWIDE APPROACHES TO SURVEILLANCE AND SCREENING

State wide and countywide efforts to enhance collaboration among medical and nonmedical providers offer some of the most promising evidence for the effectiveness of surveillance and screening. Documented outcomes include large increases in screening rates during EPSDT visits;25 a fourfold increase in early intervention enrollment, resulting in a match between the prevalence of disabilities and receipt of services26; a 75% increase in identification of children from birth to age 3 with autism spectrum disorder27; improvement in reimbursement for screening28; and, interestingly, increased attendance at well-child visits when parents’ concerns are elicited and addressed.25

The Assuring Better Child Health and Development (ABCD) Program

Created by The Commonwealth Fund, the ABCD Program has identified policy strategies for state Medicaid agencies to strengthen the delivery and financing of early childhood services for low-income families. The emphasis is on assisting participating states in developing care models that promote healthy development, including the mental development of young children. Models include developmental screening, referral, service coordination, and educational materials and resources for families and clinical providers. The program has resulted in improvements in screening, surveillance, and assessment. Most notably, work in North Carolina facilitated a 75% increase in screening, increased enrollment rates in early intervention from 2.6% to 8% (in line with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s prevalence projections), while simultaneously lowering referral age26 (http://www.nashp.org; http://www.cdc.gov/ncbdd/child/interventions.htm).

Help Me Grow

A program of the Connecticut Children’s Trust Fund, Help Me Grow links children and families to community programs and services by using a comprehensive statewide network. Components of the program include the training of child health providers in effective developmental surveillance; the creation of a triage, referral, and case management system that facilitates access for children and families to services through Child Development Infoline; the development and maintenance of a computerized inventory of regional services that address developmental and behavioral needs of children and their families; and data gathering to systematically document capacity issues and gaps in services. The program has increased identification rates of at-risk children by child health providers and increased referral rates of such children to programs and services. For example, chart reviews conducted in participating practices noted an increase in documented developmental or behavioral concerns from 9% before training to 18% after training. Furthermore, training resulted in significant differences in referral rates for certain conditions. Behavioral conditions were involved in 4% of referrals from trained practices, in comparison with 1% from untrained practices. Four percent of referrals from trained practices were for parental support and guidance, in comparison with fewer than 1% from untrained practices29 (http://www.infoline.org/Programs/helpmegrow.asp).

Promoting Resources in Developmental Education (PRIDE)

Not surprisingly, increasing rates of referral raised the likelihood of even longer waiting lists for tertiary-level developmental-behavioral pediatric evaluations. To address this challenge, the PRIDE staff sought funding from The Commonwealth Fund to study the feasibility and cost effectiveness of a model of “midlevel” developmental-behavioral pediatrics assessment (as a step between telephone triage/record review and comprehensive diagnostic evaluation) for children younger than 6 years.30

First Signs

This national and international training effort is devoted to early detection of children with disabilities, with a particular focus on autism spectrum disorders. This detection is accomplished through a mix of print materials and broadcast press, direct mail, public service announcements, presentations (to medical and nonmedical professionals), a richly informative website (www.firstsigns.org), and detailed program evaluation. Although First Signs initiatives have been conducted in several states, including New Jersey, Alabama, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, the Minnesota campaign is highlighted here because of that state’s assistance in program evaluation. Minnesota is divided into discrete service regions. Centralized train-the-trainers forums were conducted to prepare 130 professionals as outreach trainers. These individuals were from all regions of the state, and most were early interventionists, family therapists, and other nonmedical service providers. They then provided more than 165 workshops to 686 medical providers, to whom they offered individualized training tailored for health care clinics, as well as training for more than 3000 early childhood specialists. First Signs Screening Kits (which include video, information about and in some cases copies of appropriate screening tools, wall charts and parent handouts on warning signs) were distributed to more than 900 practitioners and clinics. In addition, public service announcements were aired across the state in collaboration with the Autism Society of Minnesota. Within 12 months, there was a 75% increase in the number of young children identified in the 0- to 2-year age group and an overall increase of 23% in detection of autism spectrum disorders among all children aged 0 to 21 years in that same period. The state has now expanded the initiative to include childcare providers and is educating them about red flags and warning signs. In addition, physicians with the Minnesota Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee for Children with Disabilities have begun incorporating First Signs information into physician training program at the University of Minnesota.27

Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Tennessee

Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Tennessee requested that child health providers use standardized, validated screening at all EPSDT visits. To facilitate compliance, Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Tennessee piloted a program in 34 high-volume, Medicaid-managed care practices. Outreach nurses, called regional clinical network analysts, trained providers on site how to administer, score, interpret, and submit reimbursement for the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status questionnaire (the standardized developmental-behavioral surveillance and screening instrument that elicits parents’ concerns about their children). After training, screening rates increased from 0% to 43.5% during the pilot phase. At the same time, the practices experienced a 16% increase in attendance at scheduled well-child visits, which suggests that focusing on parents’ concerns may increase their adherence to visit schedules. Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Tennessee, together with the Tennessee Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, is now providing training across the state.25 More information can be found through the Center for Health Care Strategies, “Best Clinical and Administrative Practices for Statewide” developmental and behavioral screening initiatives as established by the Center for Health Care Strategies [http://www.chcs.org/]

Healthy Steps for Young Children

This a national initiative improves traditional pediatric care with the assistance of an in-office child development specialist, whose duties include expanded discussions of preventive issues during well-child and home visits, staffing a telephone information line, disseminating patient education materials, and networking with community resources and parent support groups. Now in its 12th year, Healthy Steps followed its original cohort of 3737 intervention and comparison families from 15 pediatric practices in varied settings. In comparison with controls, Healthy Steps families received significantly more preventive and developmental services, were less likely to be dissatisfied with their pediatric primary care, and had improved parenting skills in many areas, including adherence to health visits, nutritional practices, developmental stimulation, appropriate disciplinary techniques, and correct sleeping position. In practices serving families with incomes below $20,000, use of telephone information lines increased from 37% before the intervention to 87% after; office visits with someone who teaches parents about child development increased from 39% to 88%; and home visits increased from 30% to 92%. Low-income families receiving Healthy Steps services were as likely as high-income parents to adhere to age-appropriate well-child visits at 1, 2, 4, 12, 18, and 24 months.31,32 One program evaluation suggests that Healthy Steps offers a benefit comparable with that of Head Start at about one-tenth the cost,33 although this claim is somewhat premature because Head Start data now extend to more than 35 years of follow-up research with a proven return rate of $17.00 for each $1.00 spent on early intervention, with savings realized through reductions in teen pregnancy, increases in high school graduation and employment rates, and decreased adjudication and violent crime.7 Nevertheless, Healthy Steps is extremely promising and inexpensive and includes a strong evaluation component that will answer questions about its long-term effect.

CONCLUSION

Establishing effective surveillance and screening in primary care is nevertheless challenging.13 Effective initiatives consistently offer training to providers, office staff, and nonmedical professionals. Implementation details are numerous (e.g., incorporation into existing office workflow, ordering and managing screening materials, gathering and organizing lists of referral resources and patient education handouts, identifying measures that work well with available personnel, and determining how best to communicate with nonmedical providers).18,18a,26,34 Ultimately, helping health care providers recognize the need to adopt effective detection methods is the critical first step.

1 Haggerty RJ, Roughman KJ, Pless IB. Child Health and the Community. New York: Wiley, 1975.

2 Dobos AE, Dworkin PH, Bernstein BA. Pediatricians’ approaches to developmental problems: Has the gap been narrowed? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15:34-38.

3 Institute of Medicine. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2000.

4 Blumberg SJ, Halfon N, Olson LM. The national survey of early childhood health. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1899-1906.

5 Young KT, Davis K, Schoen C, et al. Listening to parents. A national survey of parents with young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:255-262.

6 Shonkoff JP, Hauser-Cram P. Early intervention for disabled infants and their families: a quantitative analysis. Pediatrics. 1987;80:650-658.

7 Shonkoff JP, Meisels SJ. Handbook of Early Childhood Intervention, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

8 American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Children with Disabilities. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: An algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:403-420.

9 Green M, Palfrey JS, editors. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 2nd ed., Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health, 2002.

10 American Academy of Pediatrics, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110:184-186.

11 Halfon N, Regalado M, Sareen H, et al. Assessing development in the pediatric office. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1926-1933.

12 Bethell C, Reuland CHP, Halfon N, et al. Measuring the quality of preventive and developmental services for young children: National estimates and patterns of clinicians’ performance. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1973-1983.

13 Silverstein M, Sand N, Glascoe FP, et al. Pediatricians’ reported practices regarding developmental screening: Do guidelines work? And do they help? Pediatrics. 2005;116:174-179.

14 Inkelas M, Glascoe FP, Regalado M, et al: National Patterns and Disparities in Parent Concerns about Child Development. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Baltimore, 2002.

15 Glascoe FP, Dworkin PH. The role of parents in the detection of developmental and behavioral problems. Pediatrics. 1995;95:829-836.

16 Regalado M, Halfon N. Primary care services promoting optimal child development from birth to age 3 years: review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;12:1311-1322.

17 Dworkin PH. British and American recommendations for developmental monitoring: The role of surveillance. Pediatrics. 1989;84:1000-1010.

18 Glascoe FP. Collaborating with Parents: Using Parents’ Evaluations of Developmental Status to Detect and Address Developmental and Behavioral Problems. Nashville: Ellsworth & Vandermeer, 1998.

18a Houston HL, Davis RH. Opportunistic surveillance of child development in primary care: is it feasible? (Comparative Study Journal Article). J R Coll Gen Pract. 1985;35(271):77-79.

19 Glascoe FP. Toward a model for an evidenced-based approach to developmental/behavioral surveillance, promotion and patient education. Ambul Child Health. 1999;5:197-208.

20 Rydz D, Shevell MI, Majnemer A, et al. Developmental screening. Child Neurol. 2005;20:4-21.

21 Glascoe FP. Do parents’ discuss concerns about children’s development with health care providers? Ambul Child Health. 1997;2:349-356.

22 Glascoe FP, Sandler H. The value of parents’ age estimates of children’s development. J Pediatr. 1995;127:831-835.

23 Pachter LM, Dworkin PH. Maternal expectations about normal child development in four cultural groups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:1144-1150.

24 Glascoe FP. A re over-referralson developmental screening tests really a problem? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:54-59.

25 Smith PK: BCAP Toolkit: Enhancing Child Development Services in Medicaid Managed Care. Center for Health Care Strategies, 2005. (Available at: http://www.chcs.org/; accessed 10/13/06.)

26 Pinto-Martin J, Dunkle M, Earls M, et al. Developmental stages of developmental screening: Steps to implementation of a successful program. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:6-10.

27 Glascoe FP, Sievers P, Wiseman N: First Signs Model Program makes great strides in early detection in Minnesota: Clinicians and educators play major role in increased screenings. American Academy of Pediatrics’ Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Newsletter. August, 2004. (Available at: www.dbpeds.org; accessed 10/13/06.)

28 Inkelas M, Regalado H, Halfon N: Strategies for integrating developmental services and promoting medical homes. National Center for Infant and Early Childhood Health Policy, 2005. (Available at: http://www.healthychild.ucla.edu; accessed 10/13/06.)

29 McKay K. Evaluating model programs to support dissemination. An evaluation of strengthening the developmental surveillance and referral practices of child health providers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(1 Suppl):S26-S29.

30 Kelly D: PRIDE. American Academy of Pediatrics’ Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Newsletter. March, 2006 (Available at: www.dbpeds.org; accessed 10/13/06.)

31 McLearn KT, Strobino DM, Hughart N, et al. Narrowing the income gaps in preventive care for young children: Families in Healthy Steps. J Urban Health. 2004;81:206-221.

32 McLearn KT, Strobino DM, Minkovitz CS, et al. Developmental services in primary care for low-income children: Clinicians’ perceptions of the Healthy Steps for Young Children Program. J Urban Health. 2004;81:556-567.

33 Zuckerman B, Parker S, Kaplan-Sanoff M, et al. Healthy Steps: A case study of innovation in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004;114:820-826.

34 Hampshire A, Blair M, Crown N, et al. Assessing the quality of child health surveillance in primary care. A pilot study in one health district. Child Health Care Dev. 2002;28:239-249.

7C. Assessment of Development and Behavior

Assessment of child development and behavior involves a process in which information is gathered about a child so that judgments can be made. This process generally includes a multistage approach, designed to gain sufficient understanding of a child so that informed decisions can be made.1 In contrast to psychological testing (which includes the administration of tests), assessment is the process in which data from clinical sources and tools (including history, interviews, observations, formal and informal tests), preferably obtained from multiple perspectives, are interpreted and integrated into relevant clinical decisions.

Developmental and behavioral assessments may be conducted for several purposes.1,2 Screening involves procedures to identify children who are at risk for a particular problem and for whom there are available effective interventions. Diagnosis and case formulation procedures help determine the nature, severity, and causes of presenting concerns and often result in classification or a label. Prognosis and prediction methods result in generating recommendations for possible outcomes. Treatment design and planning assessment strategies aid in selecting and implementing interventions to address concerns. Treatment monitoring methods track changes in symptoms and functioning targeted by interventions. Finally, treatment evaluation procedures help investigators examine consumer satisfaction and the effectiveness of interventions.

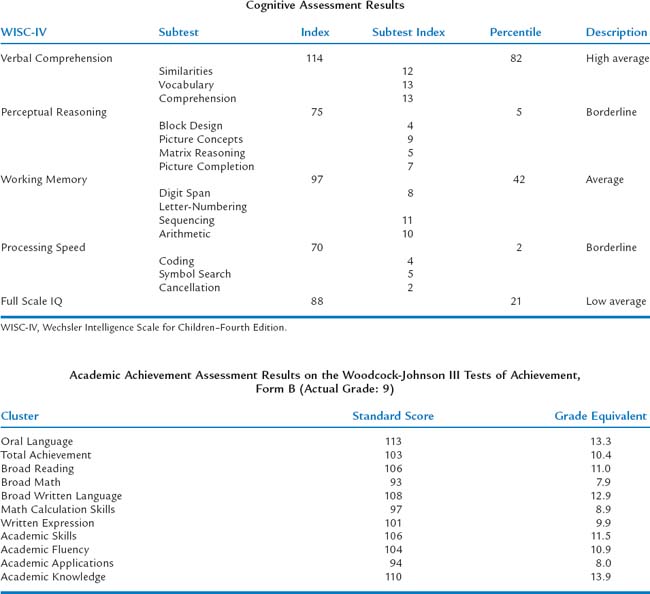

The purpose of this chapter is to describe methods and tools for assessing children’s development and behavior. In accordance with current discussions within the child psychology literature,2 we advocate the development of integrated evidence-based assessment strategies for childhood problems with emphasis placed on research concerning the reliability, validity, and clinical utility of commonly used measures in assessment and treatment planning of developmental and behavioral problems (i.e., what methods have been shown to be useful and valid for what purpose). We describe general information about clinical interviewing and observational methods required to conduct comprehensive child assessments (for more extensive discussions, see McConaughy3). To help guide the pediatric practitioner’s and researcher’s appropriate use of assessment results, we provide information on the range of methods used for assessing developmental abilities, intelligence and cognitive abilities, behavioral and emotional functioning, and specialized testing, including neuropsychological testing and measures of functional outcome. However, we do not attempt to address the complex manner in which information, obtained from different assessment data sources, is weighted and synthesized in the formulation of clinical judgments. The discussions of assessment tools is not meant to be all-inclusive—there are literally thousands of developmental and behavioral assessment measures in the literature—nor an endorsement of one instrument over others. Rather, it is a sampling the array of instruments available to clinicians and researchers (Table 7C-1). We present implications and recommendations for future research concerning measures of psychological assessment as they pertain to the field of developmental behavioral pediatrics.

TABLE 7C-1 Illustrative Behavioral and Developmental Assessment Methods

| Method | Applications | Illustrative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Structured/sem ¡structured interviews | Diagnostic assessments | |

| Assessment and treatment planning | ||

| Standardized cognitive methods | Developmental assessments | |

| Intelligence assessment | ||

| Achievement | ||

| Neuro psychological assessments | ||

| Global behavior rating scales | Broad measures of pathology | |

| Peer reports | Broad measure of pathology | Peer-Report Measure of Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior (PMIEB)81 |

| Observational coding methods | Assessment of parent child interactions | Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS)83 |

| Problem-specific questionnaires and rating scales | Depression | |

| Anxiety | ||

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | ||

| Autism spectrum disorders | ||

| Family assessment methods | Parent and family assessment | Parenting Stress Index (PSI) 3rd ed113 |

| Functional outcome methods | Global functioning | |

| Adaptive behavior | Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Vineland–II)117 | |

| Health-related quality of life | PedsQL 4.0118 |

CASE ILLUSTRATIONS

The following case examples are referred to throughout the discussion of assessment methods:

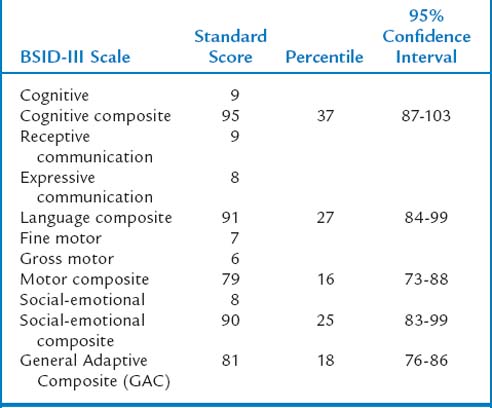

Case 1: Jane is a 21-month-old (corrected age) girl who was born at 27 weeks’ gestation, with a birth weight of 850 g, having a grade III intraventricular hemorrhage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and hyperbilirubinemia. Her young, single mother resides in low-income housing and may have used cocaine during pregnancy. Her score on the revised Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-II) Mental Developmental Index (MDI) was 90 at age 12 months (corrected age). Her developmental status is being evaluated at a high-risk infant follow-up clinic at this time to determine need for early intervention services.

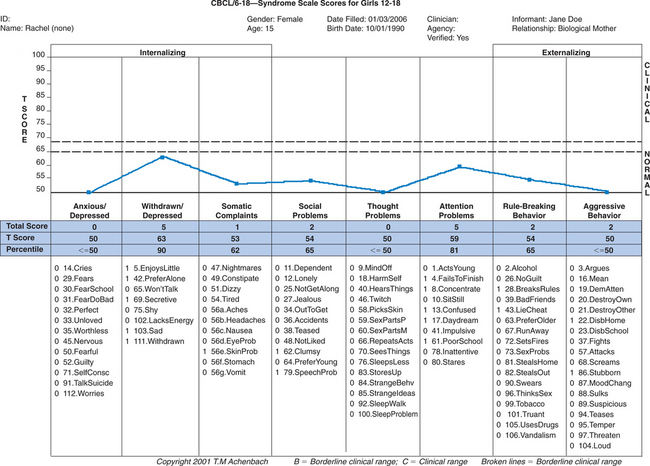

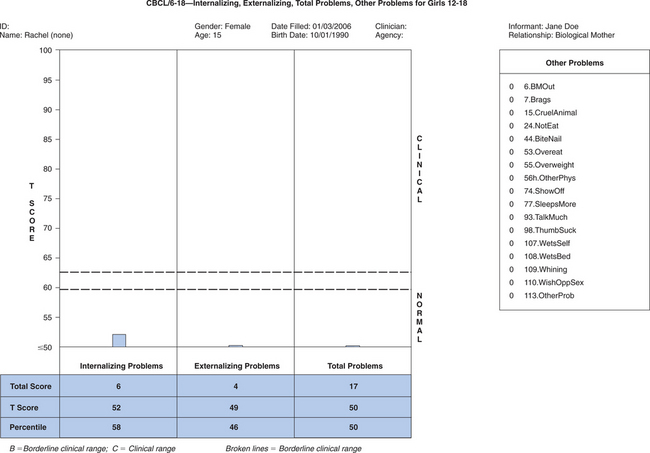

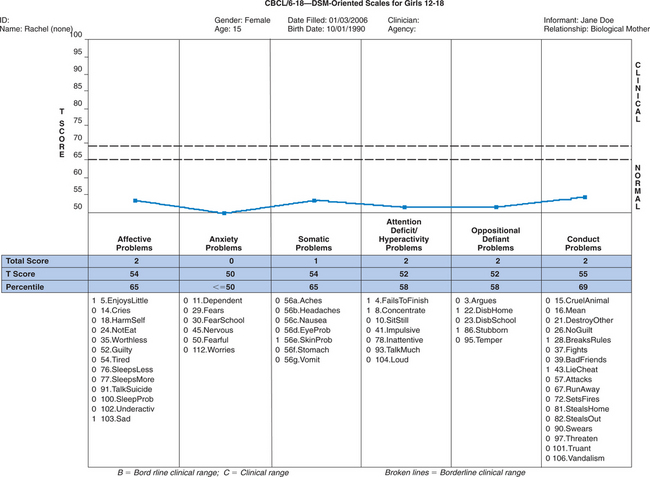

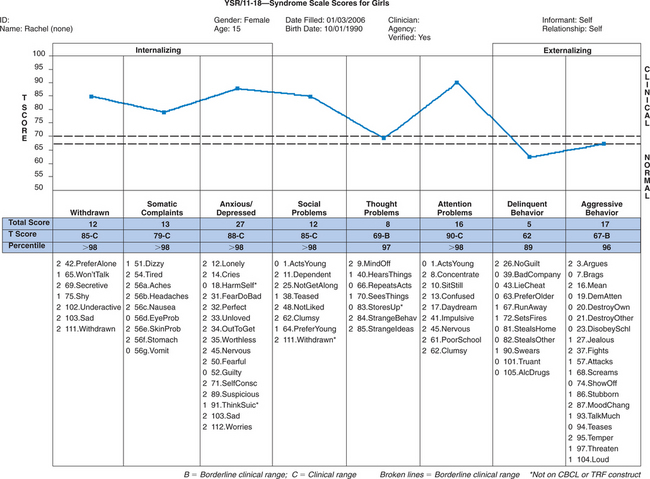

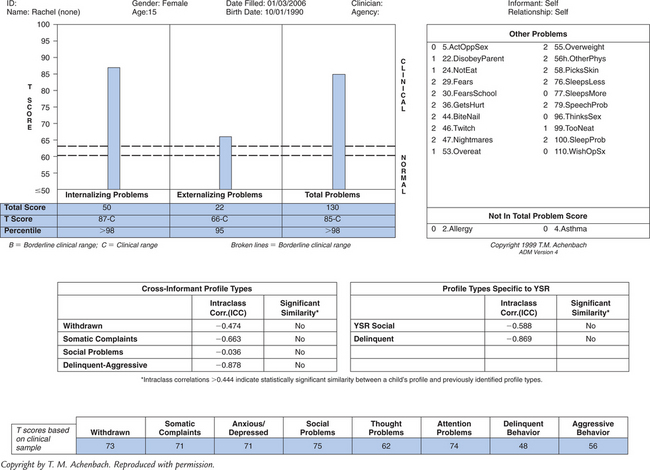

Case 1: Jane is a 21-month-old (corrected age) girl who was born at 27 weeks’ gestation, with a birth weight of 850 g, having a grade III intraventricular hemorrhage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and hyperbilirubinemia. Her young, single mother resides in low-income housing and may have used cocaine during pregnancy. Her score on the revised Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-II) Mental Developmental Index (MDI) was 90 at age 12 months (corrected age). Her developmental status is being evaluated at a high-risk infant follow-up clinic at this time to determine need for early intervention services. Case 2: Rachel is a 15-year-old girl with mild cerebral palsy with no identified learning disorders who presents with depressed mood and falling grades in her ninth grade placement. Academic strengths have been language arts, but she has always been weak in math. Historically she has been a B and C student, but in her freshman year, she is in danger of failing math. Rachel complains about trouble getting work done this year, especially in algebra. Her mother is puzzled that Rachel has requested counseling.

Case 2: Rachel is a 15-year-old girl with mild cerebral palsy with no identified learning disorders who presents with depressed mood and falling grades in her ninth grade placement. Academic strengths have been language arts, but she has always been weak in math. Historically she has been a B and C student, but in her freshman year, she is in danger of failing math. Rachel complains about trouble getting work done this year, especially in algebra. Her mother is puzzled that Rachel has requested counseling. Case 3: Jose is a 9-year-old third grader referred to the Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics Clinic because of the following problems: poor academic performance, disruptive behavior, and trouble getting along with peers. His first language is Spanish, but he is considered fluent in English. He was born in Puerto Rico, and his parents do not speak or read English. A note from his teacher indicates concerns that Jose has a short attention span and fails to complete many assignments.

Case 3: Jose is a 9-year-old third grader referred to the Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics Clinic because of the following problems: poor academic performance, disruptive behavior, and trouble getting along with peers. His first language is Spanish, but he is considered fluent in English. He was born in Puerto Rico, and his parents do not speak or read English. A note from his teacher indicates concerns that Jose has a short attention span and fails to complete many assignments.“WHAT MEASURE SHOULD I USE?”

Kazdin4 noted that in clinical situations, this question suggests a misunderstanding of the assessment process, because it is unlikely that any one measure or method can suitably capture child functioning. Although some measures have been shown to be perform better than others, a single “gold standard” tool does not exist for assessing most aspects of children’s functioning. Valid child assessment often requires data from multiple sources, including interviews, direct observations, standardized parents’ and teachers’ rating scales, self-reports, background questionnaires, and standardized tests. Multiple methods are needed not only to evaluate different facets of problems but also because of the high rate of comorbidity in children with developmental and behavioral conditions. In clinical settings, methods should be tailored to address the specific referral questions and assessment goals; therefore, preordained “assessment batteries” should be avoided. Moreover, clinical assessments often have multiple goals, such both diagnosis and treatment planning. Diagnostic methods, shown to be evidenced-based (e.g., structured diagnostic interviews or rating scales), are often not helpful in treatment planning, whereas a functional analysis of impairment (i.e., identification of environmental contexts and socially valid target behaviors) are more useful.5 Different methods of data collection yield different information, and one is not inherently better than the other; each method contributes unique elements. Moreover, assessments must adopt a framework that maintains a correct developmental perspective, including use of methods and procedures that fit a child’s developmental stage.

INTERVIEWS

Clinical assessment interviews are face-to-face interactions with bidirectional influence for the purpose of planning, implementing, or evaluating treatment.3 The interview is a fundamental technique for gathering assessment data for clinical purposes and is considered by many clinicians to be an essential component. Interviews provide respondents the opportunity to offer personal reflections of concerns and historical events. Thoughts, feelings, and other private experiences are conveyed in conversation that is not readily obtainable in any other format. The interview often serves a dual purpose. Not only does a clinical interview provide valuable assessment data, but it also is probably the first opportunity for a clinician to begin to build a positive therapeutic relationship that is the foundation for effective behavioral change. In practice, most clinical assessment interviews use unstructured or semistructured formats in order to obtain detailed information about a particular presenting problem. Greater flexibility in interview formats is often desirable when the clinical goals include not just reaching a diagnosis but also establishing a therapeutic relationship with a family and developing a treatment plan.

An effective clinical interview needs to establish a condition of trust and rapport so that the interviewee can feel comfortable in divulging personal information.6 It is important to outline the purpose and nature of the interview at the outset and to discuss issues and limits of confidentiality. Effective interviewing requires listening skills, strategic use of open-ended and direct questions, and verbal and nonverbal empathic communications. The clinician needs to offer careful statements that reflect, paraphrase, reframe, summarize, and restate to verify accurate interpretation of client statements.6 At the same time, the clinician is gathering verbal and nonverbal information conveyed by the client. Most interviewers take notes during interviews.

Most clinical assessments of children begin with a parent interview, the content of which depends on its purpose. Interviewing in the context of a developmental-behavioral problem usually focuses on identification and analysis of parental concerns so that an intervention plan can be developed and implemented. Psychosocial interviews typically elicit parent perceptions about the specific nature of the problem (including antecedents and consequences of the problem), family relations and home situation, social and school functioning, developmental history, and medical history. A practical interview format that is well suited for primary care settings is the Comprehensive Assessment to Intervention System, developed by Schroeder and Gordon.7 This behaviorally oriented format clusters information in six areas for quick response: referral question, social context of question, general information about the child’s development and family, specifics of the concern and functional analysis of behavior, effects of the problem, and areas for intervention. Schroeder and Gordon used this system both in their telephone call-in service and in their pediatric psychology office practices.

Child interviews are generally viewed as an essential component of clinical assessments and can be conducted with children as young as age 3 years.3 Child clinical interviews are useful for establishing rapport, learning the child’s perspective of functioning, selecting targets for interventions, identification of the child’s strengths and competencies, and assessing the child’s view of intervention options. Moreover, child interviews offer an opportunity to observe the child’s behavior, affect, and interaction style directly. However, competent interviewing of children and adolescents interviews requires considerable skills and knowledge of development. For example, preschool children often respond better in interviews that the interviewer conducts while sitting at the child’s level on the floor or at a small table and with toys, puppets, and manipulative items. School-age children may end communication if they feel barraged by too many direct questions, especially if asked “why” about motives, or if questions are abstract or rhetorical. Adolescent interviews may require additional attention to matters of confidentiality, trust, and respect.

Structured and Semistructured Diagnostic Interviews

An example of a structured interview is the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview for Children—IV.8 This instrument is a highly structured interview with nearly 3000 questions designed to assess more than 30, psychiatric disorders and symptoms listed in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)8a in children and adolescents aged 9 to 17 years. Parent and child versions in English and Spanish are available, and lay interviewers can administer it for epidemiological research. The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents9 is another structured diagnostic interview for children ages 6 to 17. This instrument consists of nearly 1600 questions that address 28 DSM-IV diagnoses relevant to children. Interrater reliability estimates of individual diagnoses range from poor to good, and diagnoses are moderately correlated with clinicians’ diagnoses and self-rated measures.

Semistructured interviews combine aspects of traditional and behavioral interviewing techniques. Specific topic areas and questions are presented, but, in contrast to structured interviews, more detailed responses are encouraged. Semistructured formats also support use of empathic communication described previously (e.g., reflecting, paraphrasing). For example, the Semistructured Parent Interview3 contains sample questions organized around six topic areas: concerns about the child (open ended), behavioral or emotional problems (eliciting elaboration to begin a functional analysis of behavior), social functioning, school functioning, medical and developmental history, and family relations and home situations. Like other semistructured formats, the Semistructured Parent Interview encourages parent interviews built around a series of open-ended questions to introduce a topic, followed by more focused questions about specific areas of concern.

The Semistructured Clinical Interview for Children and Adolescents (SCICA)10 is an interview designed for children aged 6 to 16. It is part of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA)11 and was designed to be used separately or in conjunction with other ASEBA instruments (e.g., Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL], Teacher Report Form). The SCICA contains a protocol of questions and procedures assessing children’s functioning across six broad areas: (1) activities, school, and job; (2) friends; (3) family relations; (4) fantasies; (5) self-perception and feelings; and (6) problems with parent/teacher. There are additional optional sections pertaining to achievement tests, screening for motor problem, and adolescent topics (e.g., somatic complaints, alcohol and drug abuse, trouble with the law). Interview information (observations and self-report) are scored on standardized rating forms and aggregated into quantitative syndrome scales and DSM-IV—oriented scales. Test-retest, interrater, and internal consistency evaluations indicate excellent to moderate estimates of reliability. Accumulating evidence for validity of the SCICA includes content validity, as well as criterion-related validity (ability to differentiate matched samples of referred and nonreferred children).

The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment12 is another semistructured diagnostic interview for children and adolescents aged 9 to 17. One interesting feature of this instrument is the inclusion of sections assessing functional impairment in a number of areas (e.g., family, peers, school, and leisure activities), family factors, and life events.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing is an empirically supported interviewing approach gaining considerable attention in medical and mental health settings. More than an assessment strategy, motivational interviewing is a brief, client-centered directive intervention designed to enhance intrinsic motivation for behavior change through the exploration and reduction of patient ambivalence.13 Based on a number of social and behavioral principles, including decisional balance, self-perception theory, and the transtheoretical model of change,14 motivational interviewing combines rogerian and strategic techniques into a directive and yet patient-centered and collaborative encounter. Assessment from a motivational interviewing perspective involves addressing the patient’s ambivalence about making a change in behavior, exploring the negative and positive aspects of this choice, and discussing the relationship between the proposed behavior change (e.g., compliance with mediations) and personal values (e.g., health). This information is elicited in an empathic, accepting, and nonjudgmental manner and is used by the patient to select goals and create a collaborative plan for change with the provider.

The effectiveness of motivational interviewing with children and young adolescents has not been established. However, there is emerging evidence of its utility with adolescents and young adults, particularly in the areas of risk behavior, program retention, and substance abuse.15,16

TESTING METHODS: DEVELOPMENTAL AND COGNITIVE

Infancy and Early Childhood

Since the 1980s, there has been increased interest in the developmental evaluation of infants and young children.17,18 This began with the 1986 Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments (Public Law 99-457) and continues with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (Public Law 108-446), a revision of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). These laws involve provision of early intervention services and early childhood education programs for children from birth through 5 years of age. Developmental evaluation is necessary to determine whether children qualify for such intervention services. Part C of the IDEA revision (Section 632) delineates five major areas of development: cognitive, communication, physical, social-emotional, and adaptive. However, definitions of delay vary, criteria being set on a state by state basis. These can included a 25% delay in functioning in comparison with same-aged peers, 1.5 to 2.0 standard deviations below average in one or more areas of development, or performance on a level that is a specific number of months below a given child’s chronological age. However, pressure to quantify development has caused professionals working with infants and young children to attribute a degree of preciseness to developmental screening and assessment that is neither realistic nor attainable. Additional problems include test administration by examiners who are not adequately trained and use of instruments that have varying degrees of psychometric rigor.19 Nonetheless, developmental evaluation is critical, because timely identification of children with developmental problems affords the opportunity for early intervention, which enhances skill acquisition or prevents additional deterioration.

Again, choice of the type of developmental assessment that is administered is driven by the purposes of the evaluation: for example, determination of eligibility for early intervention or early childhood education services, documentation of developmental change after provision of intervention, evaluation of children who are at risk for developmental problems because of established biomedical or environmental issues, documentation of recovery of function, or prediction of later outcome. Assessment of infants and young children is in many ways unique, because it occurs against a backdrop of qualitative and quantitative developmental, behavioral, and structural changes, the velocity of change being greater during infancy and early childhood than at any other time. The rapidly expanding behavioral repertoire of the infant and young child and the corresponding divergence of cognitive, motor, and neurological functions pose distinct evaluation challenges.18,19

Another significant testing concern in this age range is test refusal.20 Test refusal, where a child either declines to respond to any items, or eventually stops responding when items become increasingly difficult, occurs in 15% to 18% of preschoolers.21–24 Occasional refusals occur in 41% of young children. In addition to the immediate ramifications problematic test-taking behaviors have on actual test scores, there is evidence that early high rates of refusals are associated with similar behaviors at later ages, and with lower intelligence, visual perceptual, neuropsychological, or behavioral scores in middle childhood.22–25 Non-compliance has been reported to occur in verbal production tasks, gross motor activities, or toward the end of the testing session, and it occurs more in children born at biologic risk or those from lower socioeconomic households. Children who refuse any aspect of testing differ from those who refuse some items, or who are compliant and cooperative to a certain point and then refuse more difficult items. This situation prompted inclusion of the Test Observation Checklist (TOC) in the Stanford-Binet Scales for Early Childhood, 5th Edition (SB5).26