31 Schizophrenia

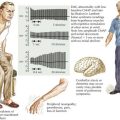

During their initial evaluation, these patients overtly express their hallucinations—usually of commanding voices, disordered thinking, and delusional beliefs (Fig. 31-1). When untreated, schizophrenia patients exhibit declining cognitive function, especially early on during their first decade of the illness. Remissions and long-term improvement are eventually possible. Nevertheless, only a minority of schizophrenic patients achieve functional recovery. Most individuals are chronically disabled, accounting for a large proportion of nursing home and some prison populations. Sadly, one of the major consequences of schizophrenia is their very high suicide rate that approaches 10%.

Clinical Presentation

Negative symptoms are equally important components of the schizophrenic profile. These typically include emotional flatness, social withdrawal, and lack of initiative and self-care (Fig. 31-1). Additionally, the schizophrenic patient usually demonstrates a cognitive disturbance, with deficits in many areas of reasoning, such as working memory and abstract reasoning.

Amador X, David A. Insight and Psychosis: Awareness of Illness in Schizophrenia and Related Disorders. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Pr.; 2004.

Cahn W, Rais M, Stigter FP, et al. Psychosis and brain volume changes during the first five years of schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008 Dec 2. Epub ahead of print

Kubicki M, Westin CF, Maier SE, et al. Uncinate fasciculus findings in schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 May;159(5):813-820.

Lavoie S. Glutathione precursor, N-acetyl-cysteine, improves mismatch negativity in schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007 Nov 14.

Marom S. Expressed emotion: relevance to rehospitalization in schizophrenia over 7 years. Schizophr Bull. 2005 Jul;31(3):751-758.

Sipos A. Paternal age and schizophrenia: a population based cohort study. BMJ. 329, 2004 Nov 6.

Straub RE, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes—famine to feast. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Jul 15;60(2):81-83.