CHAPTER 72 SCAPULOTHORACIC DISSOCIATION AND DEGLOVING INJURIES OF THE EXTREMITIES

Scapulothoracic dissociation (STD) is the traumatic disruption of the shoulder from the chest wall. It is characterized by a complete loss of scapulothoracic articulation, typically with intact skin. Vascular and neurologic injuries are common, and when severe, the result is essentially a closed forequarter amputation.1 Degloving injuries may occur to any extremity, with widely variable severity. The chapter will primarily address STD, with brief mention of the concepts associated with the management of degloving injuries.

INCIDENCE

The first report of STD was published in 1984 by Oreck and colleagues.2 The literature on the topic consists mainly of case reports, small case series, and reviews.1 One of the largest reported series consists of 25 patients, treated over a 24-year period.3 Thus, one can expect to see a case of STD approximately once a year at a major trauma center. Extremity degloving injuries, on the other hand, are much more common.

DIAGNOSIS

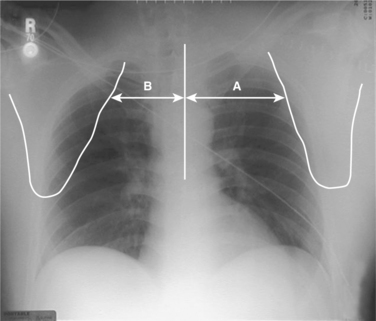

The pathognomonic radiographic finding in STD is lateral displacement of the scapula on an anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray.4 The degree of displacement may be quantified by the scapula index. This is calculated by measuring the distance from the thoracic vertebral spinous processes to the medial border of the scapula, and dividing the distance on the injured side by that on the uninjured side (Figure 1). It requires an AP chest x-ray in a supine patient with nonrotated extremities, and an uninjured shoulder.5 In the uninjured population, the scapula index averages 1.07 (±0.04).6 Zelle and colleagues3 reported an average index of 1.29 (±0.19) in a series of 25 patients with STD, but the diagnostic threshold is not well established. They noted that five of their patients had a scapula index within two standard deviations of the “normal” mean, and cautioned that it be used as a screen but not a definitive diagnostic test. Lange and Noel7 suggested simply that a difference of greater than 1 cm suggests STD, while Ebraheim and colleagues8 described alternative measurements from the sternal notch to the coracoid or glenoid margin. Because the accurate measurement of the scapula index requires a standardized x-ray and is affected by patient positioning, it is prudent to look for other clues such as distracted clavicle fractures and acromioclavicular or sternoclavicular joint disruptions, and to consider the overall clinical picture, in determining the possibility of STD.

Associated vascular injuries are very common. In a review of the literature, Damschen and colleagues4 found that 88% of patients with STD had vascular injuries. More recently, in their large single-institution experience, Zelle and colleagues3 reported vascular injuries in 16 (64%) of 25 patients. Duplex ultrasonography may be employed to document arterial flow, but arteriography is indicated in stable patients in whom STD is diagnosed or suspected, as it provides more definitive imaging. The subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries should be interrogated.

Neurologic injury is also very common with STD. Damschen and colleagues4 reported from their literature review that 94% of patients had a neurologic injury; in the series of Zelle and colleages,3 the incidence was 80%. The precise extent of injury can be difficult to determine initially. Complaints of severe pain in an anesthetic extremity are consistent with nerve root avulsion,1 but a history and physical exam predict the site of injury in just 30%–50% of cases.9 Evidence of concomitant spinal cord injury should be sought when there are any neurologic abnormalities. Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be complementary in the evaluation of these patients. A CT scan demonstrating paraspinous hematoma would be consistent with nerve root avulsion, and suggests that cervical myelography should be done.6 In the case of incomplete motor deficits, MRI is preferred.10 The T1-weighted images highlight the fat content of the spinal cord and nerve roots; the T2-weighted images highlight the water content and can demonstrate a pseudomeningocele that would suggest nerve root avulsion.1 Electromyography (EMG) studies are useful in identifying the involved nerve roots and showing evidence of denervation.9

The diagnosis of an extremity degloving injury is usually obvious on inspection, although flap viability can be difficult to determine. It is important to ascertain the presence of concomitant bony fractures, ligamentous injuries, or joint dislocations, as well as the neurovascular integrity of the extremity. This is done by thorough physical examination. The Morel-Lavallee injury deserves special mention. This is a closed degloving, in which the skin is detached from subjacent layers by a shearing force but remains intact.11 While it may not require any special treatment, it may result in skin necrosis or abscess. Additionally, if one makes an incision to operate in the area, it generally obligates open wound management.

INJURY GRADING

Damschen and colleagues4 proposed a classification system for STD in 1997, on which to base clinical decision making. In their scheme, musculoskeletal injury alone was classified type I. Type II injuries included vascular (IIA) or neurologic (IIB) injuries. An STD with both vascular and neurologic injuries was called type III. Recently, Zelle and colleagues3 examined the functional outcomes of 25 patients with STD. Their data demonstrated the pivotal importance of the neurologic injury in determining functional outcome. Consequently, they proposed a modified classification system that introduced a fourth category, type IV, which included all patients with complete brachial plexus avulsions (Table 1).

Table 1 Proposed Classification System for Severity of Scapulothoracic Dissociation

| Type | Clinical Findings |

|---|---|

| I | Musculoskeletal injury alone |

| IIA | Musculoskeletal injury with vascular disruption |

| IIB | Musculoskeletal injury with incomplete neurologic impairment of the upper extremity |

| III | Musculoskeletal injury with vascular disruption and incomplete neurologic impairment of the upper extremity |

| IV | Musculoskeletal injury with complete brachial plexus avulsion |

Adapted from Zelle BA, Pape HC, Gerich TG, et al: Functional outcome following scapulothoracic dissociation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 86:2–8, 2004.

MANAGEMENT

Most patients with STD have significant associated injuries, and thus the first step in the management of these patients is initial evaluation and stabilization based on the principles of the Advanced Trauma Life Support course of the American College of Surgeons.12 Management priorities are established with life-threatening injuries addressed first.

Hemodynamically unstable patients who appear to be exsanguinating from subclavian vessels should proceed immediately to the operating room for control and repair. Left-sided injuries should be approached via a high anterolateral or “trapdoor” thoracotomy incision, while right-sided injuries are best managed via median sternotomy with supraclavicular extension.13 Hemodynamically stable patients may undergo a more thorough diagnostic evaluation. If vascular injuries are identified by arteriography, management is dictated based on the presence of hemorrhage, location of the injury, perfusion of the distal extremity, and neurologic injury.14 Active hemorrhage must be controlled surgically, unless a branch vessel injury is amenable to angioembolization. Venous injuries may be ligated without concern for significant upper extremity swelling.15 The artery may be reconstructed with a saphenous vein graft or with a polytetrafluoroethylene graft. In the case of an exsanguinating patient, the vessel may be shunted temporarily, or ligated. If perfusion is inadequate, this may obligate amputation, but there is often sufficient collateral flow to sustain the extremity. The location of the injury dictates the approach for surgical exposure, proximal and distal control, and the appropriate level of graft interposition. An ischemic extremity must be vascularized within 4–6 hours to optimize functional outcome.4 However, it is well recognized that an arm may be adequately perfused—and have a normal brachial-brachial index—even in the case of subclavian artery occlusion, due to the extensive collateral network around the shoulder.16,17 In such a case, Sampson and colleagues17 have suggested a nonoperative approach for hemodynamically stable patients with a viable, well-perfused upper extremity. Clearly, such a treatment course must be individualized. With the growing application of endovascular stents, there is likely a role in stable patients with amenable injuries, but they cannot be recommended as a standard at this time.

The neurologic injury is a major determinant of outcome and thus of treatment. In patients undergoing surgical exploration for vascular repair, the brachial plexus should be explored. If the brachial plexus is completely avulsed, a primary above-elbow amputation is the preferred initial management, as there is essentially no chance of functional recovery of the extremity.1,3 If the brachial plexus is ruptured but not avulsed, repair is appropriate at the initial operation if the patient is a good physiologic candidate for the procedure. Nerve reconstruction does not need to be performed as an emergency but should be performed within 6 months to avoid muscle atrophy and fibrosis and as early as practically possible to minimize the scarring that will make the operation more challenging.1,8,10 Treatment options for brachial plexus injuries include nerve repair, nerve grafting, neurotization, tendon transfers, or palliative pain-relieving procedures.1 Treatment planning is facilitated by CT myelography and electromyography, done at 3 and 6 weeks after injury.6 Clements and Reisser18 suggest that nerve repair is indicated if there are fewer than three pseudomeningoceles on CT myelography. On the other hand, the presence of three or more pseudomeningoceles indicates irreparable damage and warrants above-elbow amputation. Leffert9 has suggested that the preoperative differentiation of preganglionic from postanglionic lesions facilitates planning and reduces operative time. The identification of a postganglionic lesion indicates that a proximal donor root will be available for repair or grafting. Identification of a preganglionic lesion allows the surgeon to proceed to neurotization without exploration of the brachial plexus. In this procedure, an uninjured, less important nerve is divided from its muscular insertion and attached (directly or via nerve grafts) to the distal stump of a nonfunctioning nerve.

The management of the bony injuries is a matter of some controversy. Open reduction and internal fixation may protect vascular repairs as well as facilitate early rehabilitation.4,18 The concept of the shoulder suspensory complex helps determine the need for bony fixation.19 The complex consists of the scapula, clavicle, and acromioclavicular joint, along with the ligamentous, tendinous, and supporting capsular structures. Injuries to individual components of the complex may be managed nonoperatively. However, injuries to two or more components usually result in instability and require repair. Definitive recommendations on this require further experience. If amputation is indicated, an above-elbow amputation is preferred. Early prosthetic application and rehabilitation are important in optimizing functional outcome.

MORBIDITY AND COMPLICATIONS

The major morbidity associated with STD is a flail upper extremity. Zelle and colleagues3 reported that of the 62 welldocumented cases of STD in the literature, of 40 patients who survived and did not undergo primary amputation, 24 (60%) were left with a flail extremity. In their experience, all complete brachial plexus avulsions resulted in a functionless extremity. Of seven patients with partial or no avulsion, shoulder function (as assessed by the Subjective Shoulder Rating System) was scored as poor in three, fair in two, and good in two. Long-term deficits were typically related to avulsed nerve roots. Zelle and colleagues3 argue for early primary amputation in the setting of complete brachial plexus avulsion. It avoids the problems of myoglobinuria, hyperkalemia, and vascular thrombosis. The decision should be made initially. If early amputation is refused, later amputation should be considered within the first year to improve rehabilitation and functional outcome.20 Unfortunately, patients and their families often refuse secondary amputation, despite a flail, anesthetic extremity.7,8,18 This can lead to severe causalgia, pressure sores, and injury.15,20 Furthermore, the longer the delay from injury to amputation to prosthetic fitting, the less likely the patient is to wear the prosthetic.20

MORTALITY

The STD-related mortality documented in the literature is 11%.4 However, this may be underestimated, as patients may exsanguinate from uncontrolled subclavian vessel injuries, or die of associated injuries, without STD being definitively diagnosed.

CONCLUSIONS AND ALGORITHM

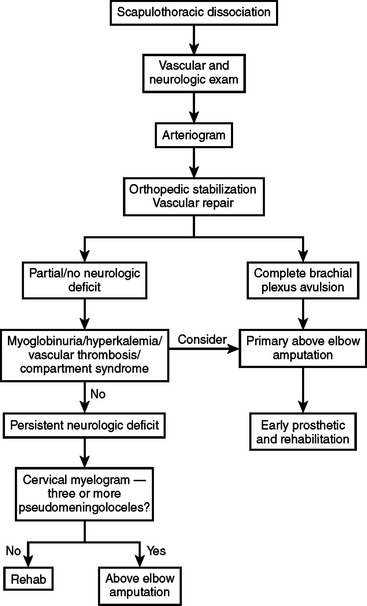

Scapulothoracic dissociation is a rare but devastating injury. Associated injuries are common. The timely diagnosis of vascular and neurologic injuries is critical. The rate of upper extremity loss is high, and many survivors are left with a flail upper extremity. Early amputation is indicated if there is a brachial plexus avulsion. A practical management algorithm, adapted from that proposed by Clements and Reisser,18 is presented in Figure 2.

1 Brucker PU, Gruen GS, Kaufmann RA. Scapulothoracic dissociation: evaluation and management. Injury. 2005;36:1147-1155.

2 Oreck SL, Burgess A, Levine AM. Traumatic lateral displacement of the scapula: a radiographic sign of neurovascular disruption. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1984;66:758-763.

3 Zelle BA, Pape HC, Gerich TG, et al. Functional outcome following scapulothoracic dissociation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2004;86:2-8.

4 Damschen DD, Cogbill TH, Siegel MJ. Scapulothoracic dissociation caused by blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42:537-540.

5 Rubenstein JD, Ebraheim NA, Kellam JF. Traumatic scapulothoracic dissociation. Radiology. 1985;157:297-298.

6 Kelbel JM, Jardon OM, Huurman WW. Scapulothoracic dissociation. A case report. Clin Orthop. 1986;209:210-214.

7 Lange RH, Noel SH. Traumatic lateral scapular displacement: an expanded spectrum of associated neurovascular injury. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:361-366.

8 Ebraheim NA, Pearlstein SR, Savolaine ER, et al. Scapulothoracic dissociation (closed avulsion of the scapula, subclavian artery and brachial plexus): a newly recognized variant, a new classification, and a review of the literature and treatment options. J Orthop Trauma. 1987;1:18-23.

9 Leffert RD. Clinical diagnosis, testing and electromyographic study in brachial plexus traction injuries. Clin Orthop. 1988;237:24-31.

10 Masmejean EH, Asfazadourian H, Alnot JY. Brachial plexus injuries in scapulothoracic dissociation. J Hand Surg. 2000;25B:336-340.

11 Kottmeier SA, Wilson SC, Born CT, et al. Surgical management of soft tissue lesions associated with pelvic ring injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:46-53.

12 American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 2004.

13 Biffl WL, Moore EE, Burch JM. Diagnosis and management of thoracic and abdominal vascular injuries. Trauma. 2002;4:105-115.

14 Katsamouris AN, Kafetzakis A, Kostas T, et al. The initial management of scapulothoracic dissociation: a challenging task for the vascular surgeon. Eur J Endovasc Surg. 2002;24:547-549.

15 Althausen PL, Lee MA, Finkemeier CG. Scapulothoracic dissociation: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;416:237-244.

16 Levin PM, Rich NM, Hutton JE. Collateral circulation in arterial injuries. Arch Surg. 1971;102:392-398.

17 Sampson LN, Britton JC, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, et al. The neurovascular outcome of scapulothoracic dissociation. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17:1083-1089.

18 Clements RH, Reisser JR. Scapulothoracic dissociation: a devastating injury. J Trauma. 1996;40:146-149.

19 Goss TP. Scapular fractures and dislocations: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:22-33.

20 Rorabeck CH. The management of the flail upper extremity in brachial plexus injuries. J Trauma. 1980;198020:491-493.