5 Salicylic Acid Peels

Introduction

Salicylic acid (ortho-hydroxybenzoic acid) is a beta hydroxy acid agent (Fig 5.1), the properties and use of which were first described by Unna, a German dermatologist. It is a lipophilic compound which removes intercellular lipids that are covalently linked to the cornified envelope surrounding cornified epithelioid cells. Owing to its antihyperplastic effects on the epidermis, multiple studies document the beneficial effects of salicylic acid as a peeling agent. Salicylic acid has also been shown to have anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. See Table 5.1.

| AHA | BHA | |

|---|---|---|

| Lipophilic | − | + |

| Anesthetic properties | − | + |

| Must be neutralized | + | − |

| Frosts | − | + |

| Useful in pregnancy and nursing | + | − |

| Safe in all skin types | + | + |

Patient Selection

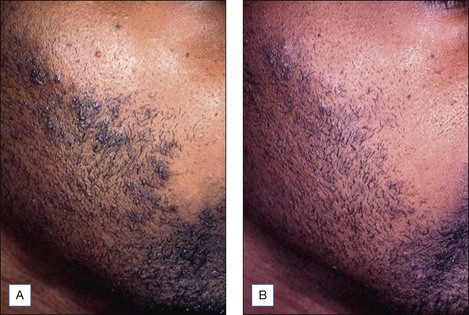

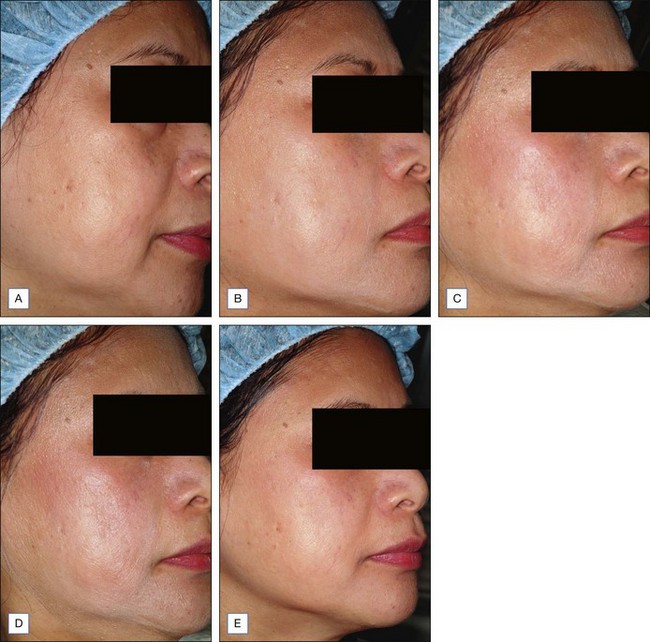

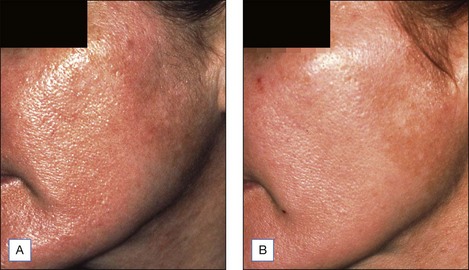

Indications for salicylic acid peels include acne vulgaris (inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions), acne rosacea, melasma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), freckles, lentigines, mild to moderate photodamage, and texturally rough skin (Figs 5.2–5.4). Salicylic acid peels are well tolerated in all skin types (Fitzpatrick’s I to VI) and in all racial/ethnic groups. See Box 5.1.

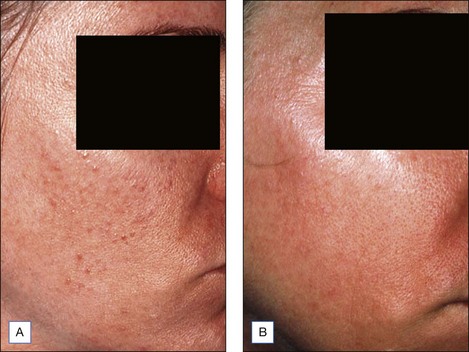

Figure 5.2 Patient with texturally rough skin before (A) and after (B) a series of five salicylic acid peels

Figure 5.4 Patient with nodulocystic acne before (A) and after (B) a series of five salicylic acid peels

Lee and colleagues treated 35 Korean patients with facial acne using 30% salicylic acid peels biweekly for 12 weeks. Both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions were significantly improved. In general, the peel was well tolerated with few side effects. Given the aforementioned findings, there are several advantages and disadvantages of salicylic acid peeling (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 Advantages and disadvantages of salicylic acid peeling

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| An established safety profile in patients with skin types I–VI | Limited depth of peeling |

| It is an excellent peeling agent in patients with acne vulgaris | Minimal efficacy in patients with significant photodamage |

| Given the appearance of the white precipitate, uniformity of application is easily achieved | |

| After several minutes the peel can induce an anesthetic effect, thereby increasing patient tolerance |

Overview of Treatment Strategy

• Patient preparation

Topical alpha-hydroxy acid or polyhydroxy acid formulations can also be used to prep the skin. In general, they are less aggressive agents in impacting peel outcomes. The skin is usually prepped for 2 to 4 weeks with a formulation of hydroquinone 4% or higher compounded formulations (5–10%) to reduce epidermal melanin. This is extremely important when treating the aforementioned dyschromias. Although less effective, other topical bleaching agents include azelaic acid, kojic acid, arbutin, and licorice. Patients can also resume use of topical bleaching agents postoperatively after peeling and irritation subsides. Broad-spectrum sunscreens (UVA and UVB) should be worn daily. See Table 5.3.

| Start | Stop | |

|---|---|---|

| Retinoids | 2–6 weeks before | 2 days before in photoaging 1–2 weeks before in PIH, melasma and in darker skin types |

| AHAs/PHAs | 2–6 weeks before | 2 days before in photoaging 1–2 weeks before in PIH, melasma and in darker skin types |

| HQ (4–10%) | 2–4 weeks before peel |

• Peel formulations

A variety of formulations of salicylic acid have been used as peeling agents. These include 50% ointment formulations (Table 5.4) as well as 20% and 30% ethanol formulations. More recently, commercial formulations of salicylic acid have become available (BioGlan Pharmaceuticals Co., Malvern, PA; Bionet Esthetics, Little Rock, AR).

| Salicylic acid ointment | Salicylic acid solutions |

|---|---|

| Salicylic acid powder USP 50% | Salicylic acid 20% |

| Methyl salicylate, 16 drops | Salicylic acid 30% |

| Aquaphor 112 g |

1 Manufacturers: BioGlan Pharmaceuticals; Bionet Esthetics

From: Swinehart 1992

• Peeling technique

Despite some generally predictable outcomes, even superficial chemical peeling procedures can cause hyperpigmentation and undesired results. Popular standard salicylic acid peeling techniques involve the use of 20% and 30% salicylic acid in an ethanol formulation. Salicylic acid peels are performed at 2 to 4-week intervals. Maximal results are achieved with a series of three to six peels (see Figs 5.2–5.4, Figs 5.5, 5.6).

The author always performs the initial peel with a 20% concentration to assess the patient’s sensitivity and reactivity. Before treatment, the face is thoroughly cleansed with alcohol and/or acetone to remove oils (Box 5.2). The peel is then applied with 2″ × 2″ (5 cm2) wedge sponges, 2″ × 2″ gauge sponges, or cotton tipped applicators. Cotton tipped swabs can also be used to apply the peeling agent to periorbital areas (Fig. 5.7). A total of two to three coats of salicylic acid is usually applied. Three coats are most often used in patients with photodamage. The acid is first applied to the medial cheeks working laterally, followed by application to the perioral area, chin, and forehead. The peel is left on for 3 to 5 minutes (Fig. 5.8). Most patients experience some mild burning and stinging during the procedure. After 1 to 3 minutes, some patients experience mild peel-related anesthesia of the face. Portable hand held fans substantially mitigate the sensation of burning and stinging.

A white precipitate, representing crystallization of the salicylic acid, begins to form at 30 seconds to 1 minute following peel application (Fig. 5.8). This should not be confused with frosting or whitening of the skin, which represents protein agglutination. Frosting usually indicates that the patient will observe some crusting and peeling following the procedure. This may be appropriate when treating photodamage. However, the author prefers to have minimal to no frosting when treating other conditions. After 3 to 5 minutes the face is thoroughly rinsed with tap water, and a bland, soapless cleanser such as Cetaphil is used to remove any residual salicylic acid precipitate. A similarly bland moisturizer is applied after rinsing. (My favorites are Cetaphil, Purpose, Theraplex, and SBR Lipocream.) Bland cleansers and moisturizers are continued for 48 hours or until all postpeel irritation and desquamation subsides. Patients are then able to resume the use of their topical skin care regimen including topical bleaching agents, acne medications, and/or retinoids.

Postpeeling Complications and Side Effects

Postpeel complications can include excessive crusting, desquamation, erythema/inflammation, and dyschromia (Fig. 5.9). Excessive desquamation and irritation are treated with low to high potency topical steroids. Topical steroids are extremely effective in resolving postpeel inflammation and mitigating the complication of PIH. In the author’s experience, any residual PIH resolves with use of topical hydroquinone formulations following salicylic acid peeling.

Aronsohn RB. Hand chemosurgery. American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery. 1984;1:24-28.

Brody HJ. Chemical peeling, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 1997.

Grimes PE. The safety and efficacy of salicylic acid chemical peels in darker racial-ethnic groups. American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. 1999;25:18-22.

Grimes PE. Agents for ethnic skin peeling. Dermatologic Therapy. 2000;13:159-164.

Hashimoto Y, Suga Y, Mizuno Y, et al. Salicylic acid peels in polyethylene glycol vehicle for the treatment of comedogenic acne in Japanese patients. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;34(2):276-279.

Jimbow K, Obata H, Pathak MA, et al. Mechanism of depigmentation by hydroquinone. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1974;62:436-449.

Kligman D, Kligman AM. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of photoaging. American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. 1998;24:325-328.

Lee HS, Kim IH. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29(12):1196-1199.

Swinehart JM. Salicylic acid ointment peeling of the hands and forearms: effective nonsurgical removal of pigmented lesions and actinic damage. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1992;18(6):495-498.