45 Sacroiliac Block

Perspective

Patient Selection

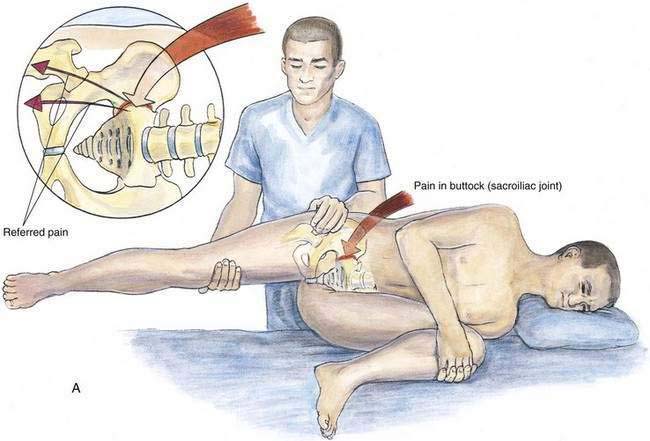

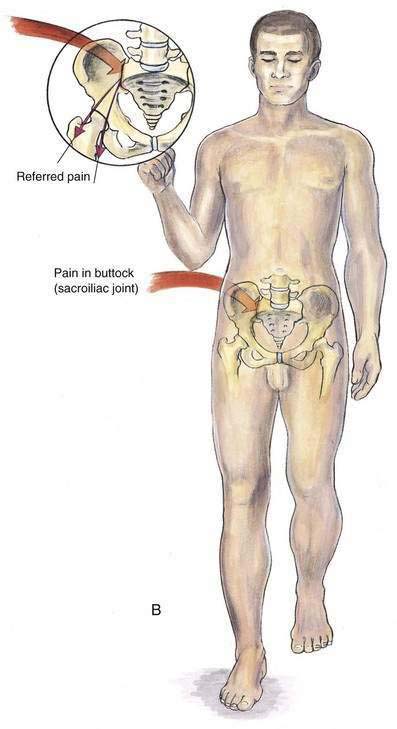

Patients undergoing evaluation for low-back pain should be evaluated clinically for sacroiliac pain. These patients typically complain of unilateral low-back pain, which often radiates into the ipsilateral buttock, groin, or leg. Often these patients have symptoms similar to those characteristic of facet joint syndromes. During the clinical examination, an increase in pain with pressure over the sacroiliac joint suggests sacroiliac pain. If such pain is present, provocative maneuvers that increase sacroiliac joint motion should be performed, such as Gaenslen’s test and the flamingo test (Fig. 45-1).

Placement

Anatomy

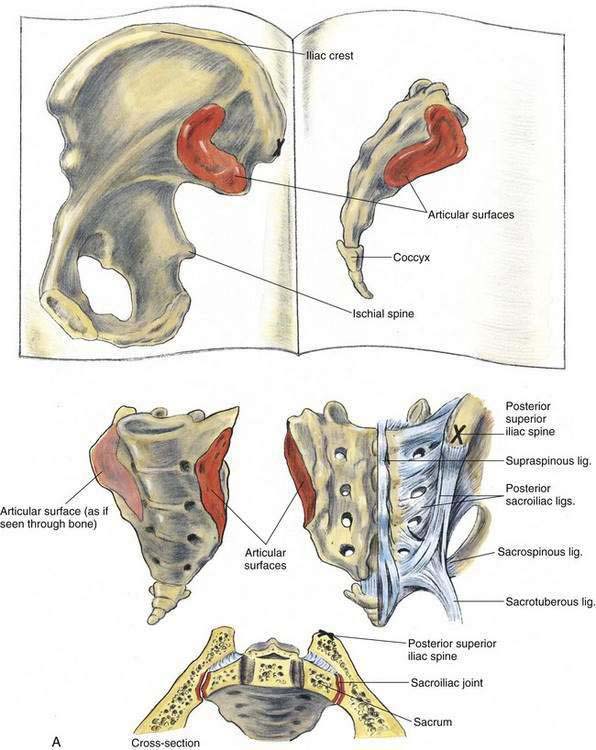

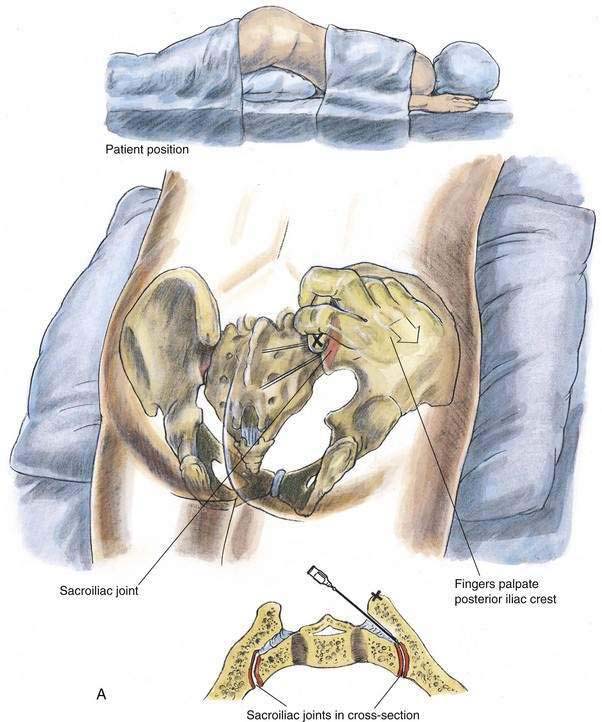

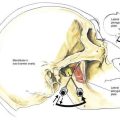

The sacroiliac joint has a well-developed joint space lined by synovial membrane with typical hyaline articular cartilage on the sacral side of the joint and a thinner layer of fibrocartilage on the iliac side. Anteriorly, the joint capsule is well developed, forming the thin anterior sacroiliac ligament. There is no joint capsule posteriorly, and the joint space is in continuity with the interosseous sacroiliac ligament. Immediately posterior to the interosseous sacroiliac ligament is the large and strong posterior sacroiliac ligament (Fig. 45-2A). The joint surfaces can rotate 3 to 5 degrees in younger, symptom-free patients, and the joint provides elasticity to the pelvic rim and serves as a buffer between the lumbosacral joint and the hip joint.

Position

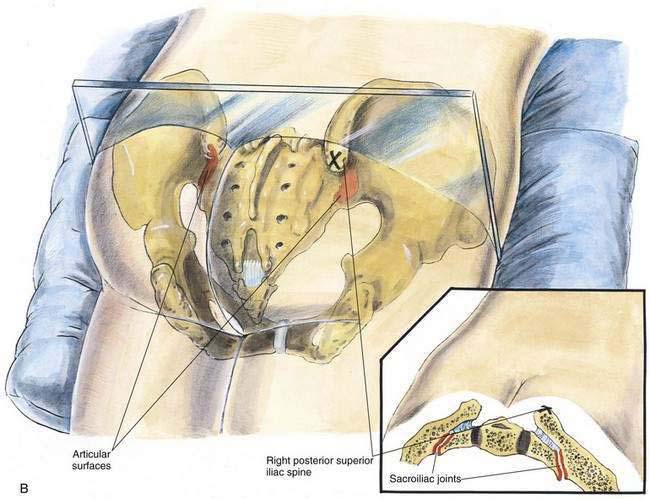

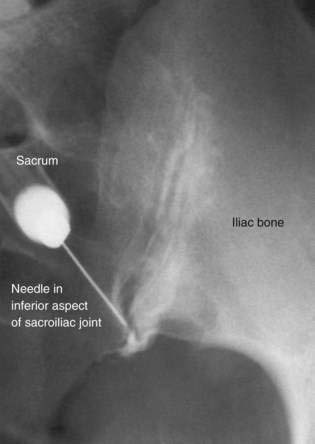

Patient position depends on whether fluoroscopy is used to confirm the position of the needle. When fluoroscopy is used, the patient is placed prone with the contralateral hip raised slightly on a pillow (approximately 20 degrees off the horizontal). This position allows the anterior and posterior orifices of the lower third of the joint to be superimposed, maximizing visualization of the joint. If fluoroscopy is not used, a pillow can simply be placed beneath the pelvis and lower abdomen with the patient prone (Fig. 45-2B).

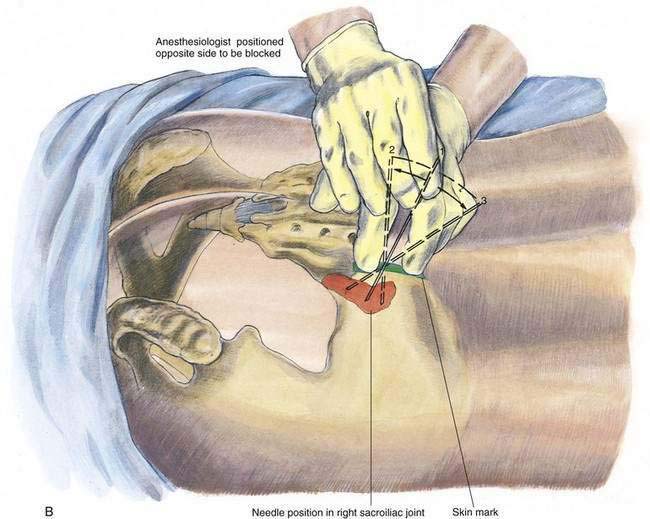

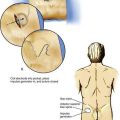

The anesthesiologist can approach the technique in one of two ways. He or she can stand on the side of the sacroiliac joint undergoing injection. This allows palpation of the sacroiliac joint with the fingers of the dominant hand from a lateral position and frees more space medially for joint injection (Fig. 45-3A). Conversely, the anesthesiologist can stand opposite the sacroiliac joint to be blocked, allowing needle insertion with the dominant hand (Fig. 45-3B).

Needle Puncture

When fluoroscopy is used for needle guidance, the patient is placed in the slightly oblique position described in the section on “Patient Position.” Fluoroscopy is used to superimpose the lower third of the anterior and posterior orifices of the sacroiliac joint, which should appear as a “Y”-shaped image (Fig. 45-4). After aseptic skin preparation and skin infiltration with local anesthetic, a 22-gauge, 7- to 9-cm needle is advanced into the lower third of the joint and its position is confirmed with radiocontrast injection. If inadequate spread of contrast medium is noted, the needle can be repositioned under fluoroscopic guidance and the cycle repeated. If no fluoroscopic needle guidance is planned, after aseptic skin preparation and local anesthetic skin infiltration, a 22-gauge, 7- to 9-cm needle on a 10-mL, three-ring control syringe is inserted in an anterolateral direction into the region between the posterior superior and the posterior inferior iliac spines. The needle may be repositioned along an arc extending between the posterior superior and the posterior inferior iliac spines, and the solution can be reinjected incrementally (see Fig. 45-3B). Again, it is typical to use approximately 5 to 10 mL of solution during these injections. In the nonfluoroscopic needle insertion, the local anesthetic–steroid solution is directed primarily at and deep to the posterior sacroiliac ligament and some of the solution may find its way into the joint. Verification of joint injection is possible only through fluoroscopy.