Chapter 114 Sacral Tumors

Regional Challenges

Tumors of the sacrum are very rare, accounting for only 2% to 4% of all primary bone neoplasms and 1% to 7% of all primary spinal tumors.1 Surgical resection, when possible, has the best long-term prognosis for most sacral tumors.2 Nonetheless, the surgical treatment of tumors in this area is challenging because of the complex regional anatomy and, often, the advanced stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis. Surgeons must not only be cognizant of local anatomy from a neurologic, colorectal, urologic, and orthopaedic standpoint, but also sometimes face the difficult conflict between functional preservation of the individual and cure of the disease process. The operating strategy requires precise and rigorous preoperative planning to locate the exact levels of tissue involvement; to make an accurate assessment of the bone, muscle, nerve, and joint structures that will require resection; and to plan pelvic reconstruction.2 This chapter focuses only on regional challenges to sacral tumors, as the anatomy and surgical approaches to the sacrum are covered more extensively elsewhere in this textbook.

Clinical Presentation

Sacral neoplasms usually grow insidiously. As a result, patients typically present with long-standing (several months to years) nonspecific symptoms, such as low-back, buttock, sacrococcygeal, or referred leg pain.1,3,4 Conventional radiographs are not sensitive, and routine lumbar myelography, CT, and MRI studies often fail to visualize the sacrum below the S2 segment. Unfortunately, many patients are misdiagnosed with lumbar disc disease for which they undergo subsequent management.

Although aggressive tumors can present earlier, the mean time to diagnosis from onset of symptoms has been reported to be 2 years.5 As a result of this common delay in making the appropriate diagnosis, sacral tumors may grow to advanced stages, with large dimensions and involvement of proximal organs and sacral nerves. According to Payer, an expansive space-occupying lesion of the sacrum usually leads to a specific pattern of clinical signs and symptoms throughout its natural history, depending on the anatomic location of the lesion within the sacrum, its extension, and whether there is compression or invasion of neighboring structures.6 Some sacral tumors have characteristic syndromes of pain due to their anatomic location and pattern of growth (chordomas, for example, may produce continuous rectal pain). 7–10

The first sign of disease may be a painless, visible sacral mass, although some patients may present with neurologic symptoms, with or without pain.11 The most common initial manifestation is local pain from mass effect.6 With subsequent tumor growth and impingement on and/or infiltration of local nerve roots, patients develop radicular pain, radiating into the buttocks, posterior thigh or leg, external genitalia, and perineum.5,12 Sacral tumor pain predominates at night and can be exacerbated by Valsalva maneuvers.5,13 Specific involvement of lumbosacral nerve roots will lead to characteristic neurologic deficits defined by the nerve or nerves involved.

Several non-neurologic clinical manifestations also can arise from sacral tumors as a result of invasion of neighboring structures. Ventral extension of a large sacral mass can present with constipation from rectal compression, as well as impede bladder emptying and uterine function.3,14–17 Lateral extension across the sacroiliac and pelvic joints can result in local joint pain that is exacerbated by weight bearing and ambulation.13,18 Constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, blood abnormalities, or weakness typically are more characteristic of metastatic lesions than of primary sacral tumors.11

By the time a sacral lesion is diagnosed, many patients may have already been mistakenly treated for lumbar spondylotic problems. Presenting factors in sacral tumors, however, may be differentiated by their insidious onset, unilaterality, and progression to involve bowel and bladder continence and/or sexual function.6,19 A small sacral mass may even be palpable on digital rectal examination during the very early stages.11

Management Consideration: Biopsy

The combination of anatomic localization and imaging characteristics, when taken in the context of a specific clinical setting, often shortens the list of possible pathologic diagnoses. Preoperative biopsy is critical to establishing a surgical plan and can be reserved for those patients in whom exact knowledge of the pathologic diagnosis would influence the decision to operate or would alter the scope of surgery. If a primary rectal malignancy with local involvement of the sacrum is suspected, endoscopy with biopsy of any suspicious endoluminal lesions is appropriate. In the case of masses extrinsic to the rectal mucosa, transrectal biopsy is discouraged, because this violation of previously uninvolved tissue planes could then commit the patient to an otherwise unneeded bowel resection.

Tumor Classification

Sacral tumors can be classified according to four broad categories: congenital, metastatic, primary osseous, and primary neurogenic.7 Specific tumor management considerations are described in the following sections.

Congenital Lesions

Congenital lesions include dermoid cysts, anterior and intrasacral meningoceles, perineural (Tarlov) cysts, teratomas, hamartomas, and chordomas. Chordoma is the most common primary neoplasm of the sacrum.15,18,20–24 These tumors typically are slow-growing, locally invasive tumors that arise from remnants of the notochord. Approximately 50% of chordomas are located in the sacrum. They can reach a large size before any symptoms manifest. These tumors typically are avascular, with a large soft tissue component centered on the midline, and expand into the presacral space. Patients at diagnosis typically are 40 to 70 years of age. They may suffer from local pain, which can be sharp or dull, usually is continuous, and often is located in the rectum, or they may present with sacral radicular pain or leg weakness and/or bladder and bowel dysfunction.3,6,17,25 Although infiltration of the gluteal muscles has been observed, the tumor does not typically involve the rectum ventrally through the presacral fascia.14,15,17 The duration of disease-free survival depends on the degree of resection; therefore, resection should extend at least one sacral segment beyond any obvious tumor involvement.3,14,26,27 Subtotal resection or curettage is done only when palliative treatment alone has been chosen because residual tumor is certain to progress.28 Chemotherapy has not demonstrated convincing efficacy, and radiation is reserved for unresectable residual or recurrent disease because it has been shown to delay time to tumor progression.29

Metastatic Tumors

Metastatic tumors are the most common malignant neoplasm in the sacrum.19 These tumors most often arise by hematogenous dissemination from solid organs such as the breast, lung, prostate, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and thyroid.30 Hematogenous malignant tumors, such as multiple myeloma, also can metastasize to the sacrum or may occur as primary lesions, as is the case with lymphoma.19,31,32 Multiple myeloma and primary lymphoma are the second and third most common primary malignant neoplasms of the sacrum, respectively.33 Pelvic organ tumors, such as adenocarcinoma of the rectum, can even infiltrate the sacrum directly.11 Because of their rapid progression and locally invasive nature, metastatic tumors often are diagnosed earlier than primary sacral lesions.31 Unfortunately, sacral involvement typically signals advanced metastatic disease: once sacral metastases are detected, 61% of cases will have distant organ involvement, and 43% of cases may have involvement of other vertebrae.4,19

Consequently, treatment often is limited to palliative radiation and/or chemotherapy. Palliative surgical intervention sometimes is indicated for decompression of neural or pelvic structures in the absence of active systemic disease. Sacrectomy may be indicated with an extended abdominoperineal resection or pelvic exenteration for locally invasive pelvic tumors in carefully selected patients.7,19

Primary Osseous Tumors

Primary osseous tumors, although histologically and biologically diverse, account for less than 10% of all primary bone tumors.7

Low-grade tumors, which include osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, osteochondroma, and aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), often are incidental findings and can present in a variety of ways. Osteoblastoma is distinguished by a lesional diameter greater than 2 cm and can present with a poorly localized, dull ache.34 Osteoid osteomas, on the other hand, produce localizing pain that is classically worse at night and is relieved by aspirin.2 Osteochondromas are slow-growing, cartilage-forming lesions that favor the dorsal elements, especially the facet joints. ABCs are composed of dilated vascular channels arising within an expanded marrow cavity. They preferentially arise in the dorsal elements but may involve the entire the sacrum. ABCs typically are discovered in individuals younger than 20 years of age, and, while histologically benign, are capable of significant sacral destruction and neurologic deficit.2,35 Most of these lesions follow an indolent course even without treatment and may even regress spontaneously. The preferred treatment is en bloc surgical resection, but curettage or subtotal resection may lead to a resolution of symptoms.

High-grade osseous tumors, which include chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma, often are very aggressive. Because these tumors respond poorly to chemotherapy and irradiation, they require a wide excision in the absence of systemic disease.36–39 Osteosarcoma sometimes is the consequence of malignant transformation of a giant cell tumor or of Paget disease. Chondrosarcoma tends to be less aggressive. Ewing sarcoma is a small, round cell malignancy of childhood and adolescence that usually originates in bone but also may arise at extraskeletal sites. Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor are regarded as closely related members of the same family of tumors. Ewing sarcoma can occur as a primary sacral lesion but has one of the highest mortality rates of all bone tumors. Ewing sarcoma is regarded as a surgical condition only when encountered in the sacrum because of its propensity to metastasize early and because of its favorable response to both irradiation and chemotherapy.40

Giant cell tumors are the second most common primary tumor of the sacrum and usually peak in the third decade of life, with a predominance in women.18,23,24,41–43 Although these tumors are histologically benign, they can degenerate into malignant sarcomatous tumors or even develop distant metastases.18,41–44 Giant cell tumors typically are slow growing but can be locally invasive and attain a very large size by the time a diagnosis is made.38 Because these tumors can have a high rate of recurrence, the preferred treatment is total resection, which may include a total sacrectomy if the tumor crosses the midline, involves the upper sacral segments, or involves the sacroiliac joints.7,45 Good local control has been reported for curettage combined with bone cement and adjunctive cryosurgery.46,47 The role of radiotherapy remains unclear, because it has been implicated in the sarcomatous transformation.42

Primary Neurogenic Tumors

Primary neurogenic tumors of the sacrum, which are relatively rare, include schwannomas, neurofibromas, ganglioneuromas, and ependymomas. Only about 1% to 5% of spinal schwannomas arise at this level.48 Similar to neurogenic lesions elsewhere in the spine, they tend to originate in the spinal canal or in close relation to the nerve roots or their coverings. These tumors typically are slow growing, often are encapsulated, are intradural or extradural, and do not invade local tissue.7 The location and slow growth of these tumors allow them to expand and fill the sacral canal and grow out of the ventral or dorsal sacral foramina to variable degrees. These tumors often remain confined to the spinal canal and may be treated with lesional excision, similar to neurogenic tumors elsewhere in the spine. In cases where the tumor is of long standing, the sacrum can become excavated from the expansion and, although the tumor maintains its bony margin, there is a “pushing” rather than an infiltrative border. Giant sacral neurofibromas, schwannomas, and ependymomas occur with equal rarity. Dorsal approaches for a curative resection are possible for schwannomas and neurofibromas, but tumors with large presacral components may require an anterior transabdominal approach.38 Ependymomas can present both intradurally and extradurally in the sacroccygeal region and can be diagnosed in advanced stages with extensive bony destruction.7 Ependymomas require complete en bloc resection to prevent local recurrence or neuroaxis dissemination via the cerebrospinal fluid. Ganglioneuromas are rare, slow-growing tumors that can grow in the pelvis from sacral extensions of the sympathetic chain. The preferred treatment is complete resection with a combined ventral and dorsal approach.38

Surgical Approaches

The complex regional anatomy, biomechanical factors, and characteristics of sacral tumors make operations in this area particularly challenging. Surgery often is performed by a multidisciplinary team that includes spine, colorectal, vascular, and plastic surgeons. Once the decision to operate has been made, the approach is dictated by several factors: the patient’s preoperative status, tumor pathology, the amount of intrapelvic disease, the degree of sacral destruction (especially the sacral ala) and presence of sacroiliac joint involvement, and whether the surgical goal is palliation or cure. Patients must be carefully selected, because sacral resections can be highly morbid procedures with subsequent permanent motor or sensory deficits or loss of bowel, bladder, and/or sexual function.7,49 In cases of planned major sacral resections, it is advisable to obtain baseline urodynamic studies to assess preoperative voiding function.

Sacral Laminectomy

The principles of dorsal dissection and exposure are fundamentally similar to those employed during lumbar laminectomy. The proximity of the incision to the anal orifice and the increased potential for wound contamination warrant extra care in skin preparation and surgical draping. A midline incision usually is chosen. The sacrospinalis, multifidus, and gluteus maximus muscles are reflected laterally off the sacrum, and blood vessels often are found penetrating the dorsal sacral foramina. Sacrifice of the dorsal rami is unavoidable but does not lead to serious functional consequences. Because of the physiologic lordosis at the lumbosacral junction, the S1 and S2 laminae may be perceived as sloping upward with respect to the L5 lamina. The laminectomy usually is started at the L5-S1 hiatus, because the interlaminar space provides a convenient point of entry into the rostral sacral canal. More restricted openings directly into the midsacral and distal sacral canals over a well-localized and very limited lesion are possible. The small advantage gained in preserving the integrity of the dorsal ligamentous attachments at L5-S1 usually is counteracted by the restricted exposure and the lost opportunity to orient to the thecal sac and exiting nerve roots. Because the ventral sacrum is fused, sacral laminectomy is not significantly destabilizing, as long as the sacroiliac joints remain intact. The lower sacral nerve roots and the filum terminale exit from the termination of the dural sac at the S2 level. The only other normal constituents of the sacral canal are the epidural vessels and fat.

Dorsal Sacrectomy

Dorsal sacrectomy, as described by MacCarty et al., is an excellent procedure for dealing with lesions of the sacrum below the level of the sacroiliac joints.50 The ability to address the presacral extension of tumor and the potential to perform a genuine oncologic procedure including en bloc resection of tumor with a circumferential margin of uninvolved tissues distinguishes this from simple sacral laminectomy. These advantages are particularly relevant to osseous lesions of the sacrum, which more often are malignant and are more likely to present with a presacral mass. This approach usually is suitable for tumors whose superior limit can be reached on digital rectal examination; it should not be employed in cases with primary rectal involvement.

Dorsal sacrectomy works well for smaller lesions of the midsacrum and distal sacrum that do not yet require resection through the level of the sacroiliac joint. Although MacCarty et al. described amputation as high as the first sacral segment, this method is less attractive because the ability to accurately dissect tissue planes of the upper presacrum is unpredictable from this approach and risks a major vascular injury, inadvertent entry into the rectum, or violation of the tumor capsule during attempts to osteotomize the ventral sacrum and sacroiliac joints from behind.50 These difficulties are best addressed by combining the techniques of dorsal sacrectomy with a ventral approach for lesions requiring amputation through the level of the sacroiliac joints.

Combined Ventral and Dorsal Approach to Sacral Resection

A sequential ventral and dorsal approach to facilitate high sacral amputation was described by Bowers in 1948.51 Transabdominal exposure was used to gain control of the hypogastric vessels and permit a safer dorsal sacrectomy. The ventral approach allows mobilization of the rectum off of the tumor under direct vision rather than by blind finger dissection. Furthermore, should the rectum be involved by tumor, either as a consequence of direct extension or because of seeding from an injudicious transrectal biopsy, it can be isolated for en bloc resection with the sacral specimen. This is impossible from the dorsal approach alone.

Localio et al. popularized a synchronous abdominosacral approach for sacral lesions.52 They favored a lateral decubitus position to allow simultaneous ventral and dorsal exposure without requiring patient repositioning. The abdominal approach begins through an obliquely oriented flank incision centered midway between the costal margin and the iliac crest. The retroperitoneum is dissected, and the descending colon and rectum are mobilized rightward. The internal iliac arteries and veins are controlled with vessel loops, and the entire perimeter of the tumor mass is defined ventrally. Tumor vessels, which usually emanate from the lateral and median sacral arteries, are interrupted directly. The sacrum is exposed through a separate dorsal incision, and with division of the anococcygeal ligament, the two wounds become communicating. As with dorsal sacrectomy, the lateral muscular attachments onto the sacrum and sacroiliac joint are released. With the hypogastric vessels temporarily occluded, the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments are detached, and the posterior sacroiliac ligaments are divided rostrally up to the intended level of amputation. The sacrum and sacroiliac joint can then be osteotomized ventrally and dorsally under direct vision. Localio et al. suggested that this technique of synchronous abdominosacral resection resulted in less blood loss than did sequential resection.52 Simpson et al. reported their experience with 12 patients with tumors in the cephalad part of the sacrum managed with a modified simultaneous ventral and dorsal approach via an ilioinguinal incision extended circumferentially around the body wall to the midline dorsally.53 Although it is possible to expose the sacrum ventrally and dorsally simultaneously in the lateral position, it is more difficult to expose both of them well. The lateral position complicates efforts at soft tissue reconstruction and mechanical stabilization that are integral to the success of these procedures.

A sequential ventral and dorsal approach with pedicled rectus abdominis pull-through flap reconstruction is favored for high sacral resections (this often is performed with the aid of a plastic surgeon). The technique of surgical resection is essentially similar to that described by Stener and Gunterberg.54 The rectus abdominis pull-through flap originally was described for reconstruction and repair of perineal wounds.55,56 Its routine use in the closure of the large surgical voids created by high sacrectomy has virtually eliminated problems with prolonged wound drainage and breakdown.57–59 Although the surgery is necessarily interrupted by the need for patient repositioning, the superior visibility and the working ease made possible through the sequential approach more than justify this inconvenience.

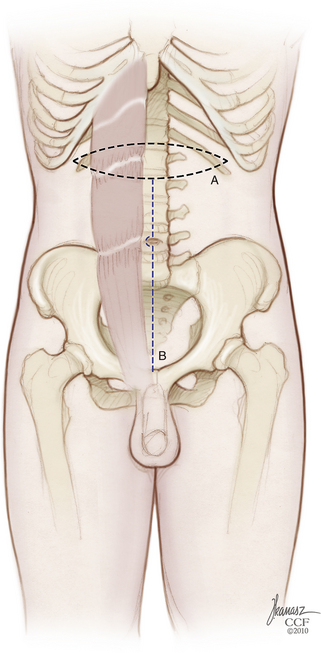

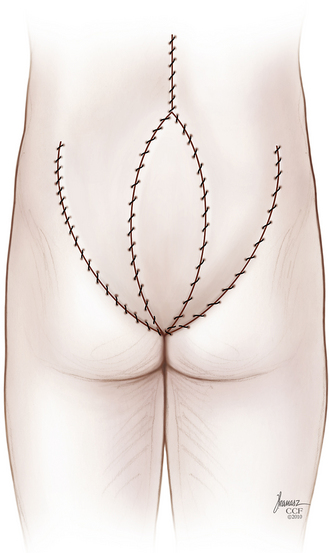

A mechanical bowel preparation is begun preoperatively, and broad-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis is initiated. Because blood loss can be substantial (7–80 L in some series), adequate transfusion reserves and IV lines for volume resuscitation are placed in advance.60,61 The cell saver can be used, except in cases of malignant tumor. The operation begins with abdominal exposure. Incisions for a transversely oriented myocutaneous flap based on the upper rectus abdominis muscles are outlined in the epigastrium; a midline lower abdominal entry is employed (Fig. 114-1). Although the sacrum can be exposed ventrally by bilateral extraperitoneal dissection, a transperitoneal route usually is preferred. After the bowel has been “packed off,” the dorsal parietal peritoneum is opened unilaterally, the ureters are identified, and the iliac vessels are dissected bilaterally. If the rectum is to be spared, it is mobilized off of the tumor capsule ventrally after incision of the retrorectal peritoneal reflection. The tumor capsule is outlined circumferentially. Bleeding from the venous plexus in the loose areolar tissue surrounding the tumor can be profuse. Internal iliac and middle sacral arteries and veins are ligated along with any tumor vessels, and both external arteries should be preserved.62 It may not be possible to attain absolute hemostasis until after the tumor is completely resected.

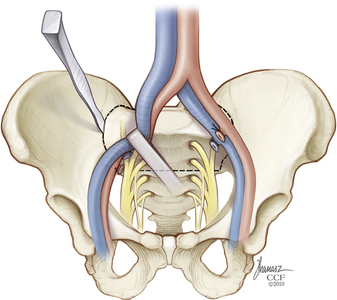

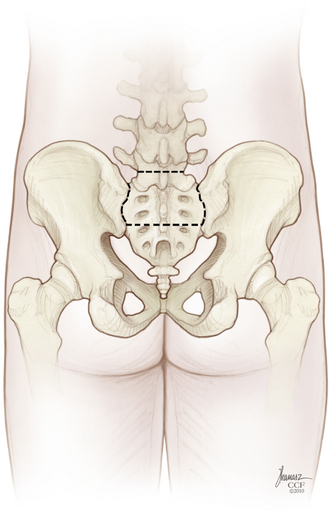

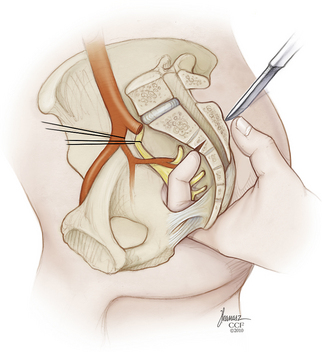

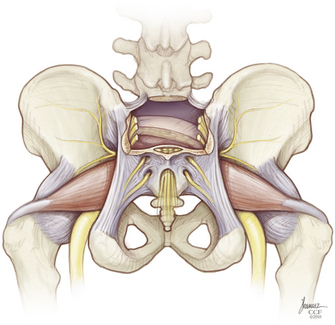

High sacral resections require mobilization of the iliac veins medially and laterally during the osteotomies (Fig. 114-2). The surgeon is advised to preemptively ligate the iliolumbar veins, entering through the back wall to avoid avulsion and a potential source of troublesome bleeding. The sacral foramina are visualized ventrally and serve as landmarks to guide the ventral sacral osteotomy. The peritoneal investment and periosteum are incised transversely at the sacral promontory, and the incision is reflected downward to the level of the intended amputation. Inevitably, this measure divides the sympathetic trunks and, in high sacral resections, also sacrifices the hypogastric plexus. The lumbosacral nerve trunks coursing caudolaterally over the sacral alae and the sacroiliac joints are dissected free and protected. A transverse osteotomy is then begun through the ventral sacrum at the selected level (see Fig. 114-2). Usually this incorporates the ventral sacral foramina, in which case the sacral nerves exiting at that level are first dissected out and preserved. If the osteotomy must transect the midbody of S1 above the foramina, it will not be feasible to save any of the sacral nerves. Because the midportion of the osteotomy enters the sacral canal, it is best to perform this step with a chisel to minimize the chance of premature entry into the thecal sac. The bone cuts are extended inferolaterally into the sacroiliac joints, with care taken to protect the lumbosacral trunks and any remaining sacral roots. The apically convex course of the osteotomy parallels the path of the nerves to be spared. A chisel osteotome is favored for this, as saws and drills are more apt to entrain adjacent soft tissues. The peritoneal investment and the periosteum are incised caudally as far as the greater sciatic notch, and the cortex is scored ventrally to create a stress riser that facilitates subsequent completion osteotomy from behind. Waxing the osteotomy cuts helps reduce bleeding and improves visibility. A commonly used alternative involves the passage of a Gigli saw through the sacral foramina to be picked up from the posterior approach.

In those cases in which the rectum is to be resected, the rectosigmoid junction is mobilized in preparation for division with a mechanical stapler. The stapled-closed stumps of bowel may then be invaginated and oversewn with serosal sutures to lessen the chances of wound soilage. The rostral and middle rectal vessels are isolated and divided, and the rectovesical or rectouterine peritoneal reflection is incised to allow access to the pelvic floor. Peritoneal adhesions between the tumor mass and the bladder or pelvic side walls should not be simply lysed, because this may indicate a need for pelvic exenteration if the surgery is to have a curative intent. Wide local excision, including bladder, prostate, vagina, cervix, or endopelvic fascia, and contained vessels, may be required in such cases.63,64 Access for deep pelvic dissection can be enhanced through division of the symphysis pubis and introduction of a rib spreader to open the pelvic ring ventrally.

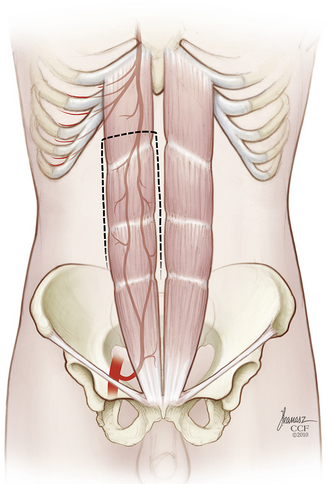

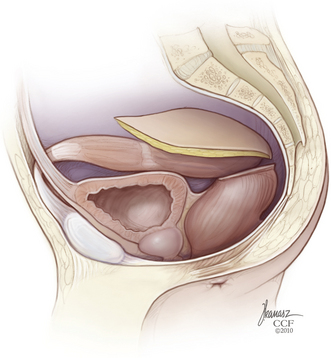

At this point, a rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap based on the inferior epigastric vessels is prepared (Fig. 114-3). The ventral abdominal wall skin island is sealed with iodine-impregnated plastic adhesive dressing and then stowed within the pelvis (Fig. 114-4). It may be helpful for the purpose of hemostasis and for anatomic demarcation during the subsequent dorsal approach to place large sheets of gelatin sponges, silicone elastomer (Silastic, Dow Corning, Midland, MI), or Gore-Tex (W. L. Gore and Associates, Inc., Elkton, MD) into the plane of dissection between the sacrectomy specimen, with any attached presacral mass and the iliac vessels, sacral plexi, and ureters remaining undisturbed. If required, a colostomy is performed, and the wound is closed layer by layer.

FIGURE 114-4 The rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap is then stowed within the pelvis. (Copyright Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

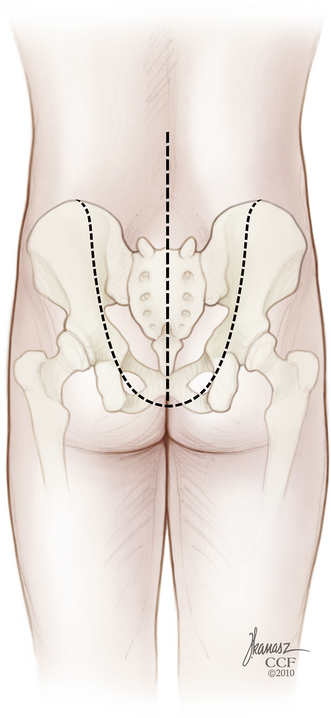

The patient is then repositioned prone on a padded thoracoabdominal rest, allowing the abdomen to hang free. A dorsal midline incision extending from the L5-S1 interlaminar space to the level of the external anal sphincter is outlined (Fig. 114-5). If the rectum is to be included with the specimen, the caudal limb of the incision continues as an ellipse encircling the anus. Alternatively, the perineal dissection may be performed during the abdominal exposure if the patient is operated in the lithotomy position with the buttocks elevated on a small cushion. Any skin compromised by tumor, previous biopsy, radiation-induced change, or prior surgery should be excised with the specimen. Dissection through the soft tissues is deepened in a conical fashion: at the summit is any involved skin and at the base is the biopsy tract and any tumor erupting out of the dorsal sacrum (see Fig. 114-5). This again reemphasizes the objective of an en bloc resection with a margin of healthy, uninvolved tissues.

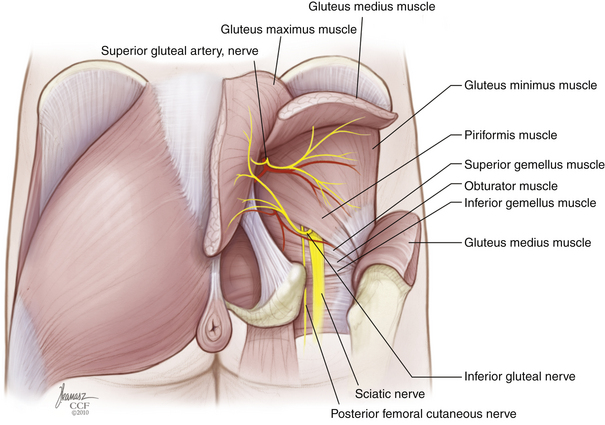

Rostrally, the interspinous and interlaminar ligaments at L5-S1 are dissected out to enable isolation of the thecal sac in preparation for its ligation immediately below the level of exit of the last nerve roots to be preserved. If the S2 roots are to be spared, a limited rostral sacral laminectomy is needed to allow their visualization. Dorsally, the sacrospinalis muscles are sectioned transversely, and the dorsal sacroiliac ligament is released from the ilium (Fig. 114-6). Laterally, the gluteal musculature is transected, leaving a cuff attached at its sacral origin. This uncovers the piriformis muscles, which are, in turn, divided at their musculotendinous junction. The superior gluteal vessels and nerves are found at the upper border of the piriformis, and the inferior gluteal vessels and the sciatic, pudendal, and posterior femoral cutaneous nerves are found exiting the pelvis at its lower edge. These should be identified carefully and preserved whenever possible. If rectal resection is not planned, the caudal border of the specimen is freed by division of the anococcygeal ligament just proximal to the anal sphincter. The sacrotuberous ligament is detached from the ischial tuberosity, and the coccygeal muscles are cut. The sacrospinous ligament is conveniently detached by an osteotomy cut across the base of the ischial spine. If the rectum is to be included with the specimen, the anus is dissected circumferentially with additional division of the levator musculature.

The soft tissue dissection is now finished, and the field is prepared for completion osteotomy (Fig. 114-7). A finger is introduced through the anococcygeal interval and the greater sciatic notch on either side to redevelop the presacral space and palpate the previously outlined osteotomy cuts from within the pelvis (Fig. 114-8). This helps guide the dorsal cuts to ensure an accurate intercept with the ventral osteotomies. The osteotomy along the ilium can exit into the sciatic notch either medial or lateral to the ischial spine. The sacrum is free and can be lifted out of the wound dorsally when the lower sacral roots coursing laterally toward the sacral plexi and pudendal nerves are sequentially divided (Fig. 114-9). Bleeding can be profuse at this stage—bone edges should be waxed expeditiously and bleeding from larger vessels promptly secured with ligatures or hemoclips.

Removal of the sacrum in this manner creates a large trapdoor opening into the pelvis. It is desirable to obliterate as much of this dead space as possible. Toward this end, the gluteal muscles can be reapproximated to bone or to one another, a measure that also may enhance their function postoperatively by reestablishing an origin for them. Large-bore, bulb-type closed suction drains are placed into the wound after copious antibiotic irrigation. The rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap is now retrieved through the sacrectomy window, trimmed, and sewn into place in a layered fashion (Fig. 114-10). We have been far more satisfied with this reconstructive method than with the alternatives of primary closure or reconstruction with reversed latissimus dorsi flaps, gluteal flaps, or gracilis flaps. Microvascular free flap reconstruction is another option; however, it further escalates the technical requirements of an already demanding procedure. The rectus abdominis pull-through flap is recommended, especially in circumstances of previous surgery or irradiation, when the prospects for successful primary closure are remote. It largely averts problems with rectal prolapse into the wound during defecation and obviates the need for mesh closure of the dorsal peritoneal or fascial defect.

Total Sacrectomy

Tumors in which surgical extirpation requires total or near-total sacrectomy present an additional challenge because of the difficulties in reestablishing lumbopelvic stability. Integrity of the pelvic ring depends on ligamentous stabilization ventrally at the pubic symphysis and dorsally at each of the sacroiliac joints. Although the precise extent of sacroiliac joint that must be preserved to maintain clinical stability is unknown, cadaveric studies have shown that patients can bear weight as long as at least 50% of the sacroiliac joint remains intact.54,65 Involvement of the upper S1 segment has been regarded by some surgeons as a contraindication to surgery because of the extreme instability that would result from its resection. Certainly, if less than 50% of the sacroiliac joint remains intact, strong consideration should be given to supplemental stabilization to prevent low back pain and instability.

With the spine functionally disconnected from the sacrum, lumbopelvic reconstruction is highly recommended but may not be mandatory.66 Various lumbopelvic reconstruction techniques have been reported in the literature. These include sacroiliac joint screw fixation, iliac-sacral screw fixation, posterior iliosacral plating and screw fixation, custom-made prosthesis, Galveston rod fixation, iliac screws, and transiliac rods.45,67–75 Chapter 152 provides a review of current state-of-the-art complex lumbosacropelvic reconstruction techniques.

Postoperative Considerations

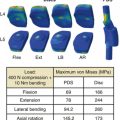

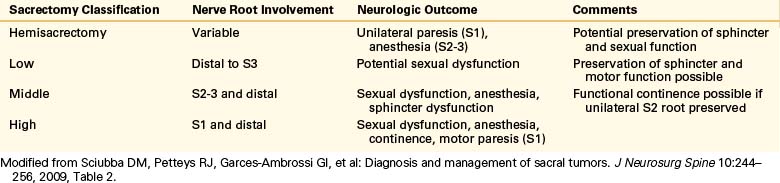

The level of sacral amputation correlates well with the expected neurologic deficit and postoperative function7,76 (Table 114-1). High resection of S1 nerve roots usually results in significant motor impairment, loss of sphincter control, and sexual dysfunction. Middle resections involving S2-3 can, infrequently, lead to motor dysfunction, but saddle anesthesia and sphincter dysfunction are common. Low amputations distal to S2 typically lead to minimal deficit, with preservation of sphincter and motor function but possible sexual dysfunction. Bowel and bladder function seem to remain fairly normal when both S3 roots or the unilateral S1-5 roots are spared.77,78 The objective of providing a patient with a true oncologic procedure, however, should not be compromised by the attempt to preserve continence. In males, the extensive dissection of the sympathetic and parasympathetic plexi will expectedly diminish erectile function and the capacity for antegrade ejaculation. Patients need to be counseled preoperatively about the potential consequences of sacral resection for anogenital and reproductive function.

Table 114-1 Expected Dysfunction Following Sacral Tumor Resection Based on Sacral Nerve Roots Sacrificed

The main sources of surgical mortality in upper sacral resection are intraoperative blood loss and postoperative wound sepsis. These have generally ranged between 0 and 15% in various reports.52,64,68,79,80 Embolization of sacral tumors is a useful adjuvant therapy that can aid in surgical management by reducing intraoperative blood loss for benign, malignant, and metastatic lesions of the sacrum.81 Wound complications, including prolonged drainage, delayed breakdown, infections, seromas, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, and pelvic prolapse, were common in the past and probably have been underreported. Sung et al.79 and Touran et al.80 have acknowledged wound complication rates of 11% and 25%, respectively.

Summary

Sacral tumors pose a formidable challenge because of their rarity and the difficulty in diagnosis and treatment. Most tumors arising in the sacral canal or in the distal bony sacrum are well handled by conventional techniques. Tumors with more proximal involvement necessitating total sacrectomy, however, pose the greatest management challenges. Sacrectomy for malignant disease remains a highly morbid undertaking with a significant chance for local failure. At times, past results have been compromised by an insufficient appreciation of the need for en bloc resection of malignant lesions with an inviolate margin of normal tissue. Otherwise, patients may be condemned to early recurrence or remote dissemination. At other times, surgical efforts have been diminished by suboptimal wound closure. The best results are achieved by drawing on the expertise of a multidisciplinary surgical team. The collaboration of oncologic, plastic, urologic, and orthopaedic surgeons may be of major assistance to the spine surgeon who undertakes a high or total sacral resection. Physical methods of tumor extirpation are relatively crude, and biologic barriers will be overcome only when these mechanical techniques can be combined with therapies directed toward the molecular genetics of the neoplastic process itself.

Cahill D. Surgical approaches to the lumbar spine and sacrum. In: Rea G., editor. Spine tumors. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 1994.

Fourney D.R., Gokaslan Z.L., . Sacral tumors: primary and metastatic. Fehlings M., Dickman C.A., Gokaslan Z.L. Spinal cord and spinal column tumors: principles and practice. New York: Thieme. 2006:404-419.

Manaster B.J., Graham T. Imaging of sacral tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(2):E2.

Payer M. Neurological manifestation of sacral tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(2):E1.

Sciubba D.M., Petteys R.J., Garces-Ambrossi G.L., et al. Diagnosis and management of sacral tumors. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10(3):244-256.

Zhang H.Y., Thongtrangan I., Balabhadra R.S., et al. Surgical techniques for total sacrectomy and spinopelvic reconstruction. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(2):E5.

1. Feldenzer J.A., McGauley J.L., McGillicuddy J.E. Sacral and presacral tumors: problems in diagnosis and management. Neurosurgery. 1989;25(6):884-891.

2. Gerber S., Ollivier L., Leclère J., et al. Imaging of sacral tumours. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(4):277-289.

3. York J.E., Kaczaraj A., Abi-Said D., et al. Sacral chordoma: 40-year experience at a major cancer center. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(1):74-79. discussion 79-80

4. Ozdemir M.H., Gürkan I., Yildiz Y., et al. Surgical treatment of malignant tumours of the sacrum. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25(1):44-49.

5. Norstrom C.W., Kernohan J.W., Love J.G. One hundred primary caudal tumors. JAMA. 1961;178:1071-1077.

6. Payer M. Neurological manifestation of sacral tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(2):E1.

7. Sciubba D.M., Petteys R.J., Garces-Ambrossi G.L., et al. Diagnosis and management of sacral tumors. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10(3):244-256.

8. Gray S.W., Singhabhandhu B., Smith R.A., Skandalakis J.E. Sacrococcygeal chordoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Surgery. 1975;78(5):573-582.

9. Kamrin R., Potanos J.N., Pool J. An evaluation of the diagnosis and treatment of chordoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1964;27:157-165.

10. Sundaresan N., Galicich J.H., Chu F.C., Huvos A.G. Spinal chordomas. J Neurosurg. 1979;50(3):312-319.

11. Varga P.P., Bors I., Lazary A. Sacral tumors and management. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40(1):105-123.

12. Golner J. Pain: extremities and spine-evaluation and differential diagnosis. In: Omer G.E., Spinner M., editors. Management of peripheral nerve problems. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980:404-419.

13. Wilson S. Neurology. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1940;Vol. 2.

14. Chandawarkar R. Sacrococcygeal chordoma: review of 50 consecutive patients. World J Surg. 1996;20(6):717-719.

15. Cheng E.Y., Ozerdemoglu R.A., Transfeldt E.E., Thompson R.C.Jr. Lumbosacral chordoma. Prognostic factors and treatment. Spine. 1999;24(16):1639-1645.

16. Lin P.P., Guzel V.P., Moura M.F., et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with giant cell tumor of the sacrum treated with selective arterial embolization. Cancer. 2002;95(6):1317-1325.

17. Yonemoto T., Tatezaki S., Takenouchi T., et al. The surgical management of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Cancer. 1999;85(4):878-883.

18. Smith J., Wixon D., Watson R.C. Giant-cell tumor of the sacrum. Clinical and radiologic features in 13 patients. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1979;30(1):34-39.

19. Nader R., Rhines L.D., Mendel E. Metastatic sacral tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:453-457.

20. Mirra J.M., Picci P., Gold R.H. Bone tumors: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic correlations. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1989.

21. Higinbotham N.L., Phillips R.F., Farr H.W., Hustu H.O. Chordoma. Thirty-five year study at Memorial Hospital. Cancer. 1967;20(11):1841-1850.

22. Kaiser T.E., Pritchard D.J., Unni K.K. Clinicopathologic study of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Cancer. 1984;53(11):2574-2578.

23. Sar C., Eralp L. Surgical treatment of primary tumors of the sacrum. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122(3):148-155.

24. Xu W.P., Song X.W., Yue S.Y., et al. Primary sacral tumors and their surgical treatment. A report of 87 cases. Chin Med J (Engl). 1990;103(11):879-884.

25. Bergh P., Kindblom L.G., Gunterberg B., et al. Prognostic factors in chordoma of the sacrum and mobile spine: a study of 39 patients. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2122-2134.

26. Rich T.A., Schiller A., Suit H.D., Mankin H.J. Clinical and pathologic review of 48 cases of chordoma. Cancer. 1985;56(1):182-187.

27. Sundaresan N., Huvos A.G., Krol G., et al. Surgical treatment of spinal chordomas. Arch Surg. 1987;122(12):1479-1482.

28. Ishii K., Chiba K., Watanabe M., et al. Local recurrence after S2-2 sacrectomy in sacral chordoma. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(suppl 1):98-101.

29. Catton C., O’Sullivan B., Bell R., et al. Chordoma: long-term follow-up after radical photon irradiation. Radiother Oncol. 1996;41(1):67-72.

30. Kollender Y., Meller I., Bickels J., et al. Role of adjuvant cryosurgery in intralesional treatment of sacral tumors. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2830-2838.

31. Disler D.G., Miklic D., . Imaging findings in tumors of the sacrum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173;6:1699-1706.

33. Manaster B.J., Graham T. Imaging of sacral tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(2):E2.

34. Camins M., Oppenheim J.S., Perrin R. Tumors of the vertebral axis: benign, primary malignant, and metastatic tumors. In: Youmans J., editor. Neurological surgery. ed 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996:3134-3167.

35. Papagelopoulos P.J., Choudhury S.N., Frassica F.J., et al. Treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts of the pelvis and sacrum. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2001;83(11):1674-1681.

36. Shives T.C., Dahlin D.C., Sim F.H., et al. Osteosarcoma of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1986;68(5):660-668.

37. Shives T.C., McLeod R.A., Unni K.K., Schray M.F. Chondrosarcoma of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71(8):1158-1165.

38. Fourney D.R., Gokaslan Z.L. Sacral tumors: primary and metastatic. In: Fehlings M., Dickman C.A., Gokaslan Z.L., editors. Spinal cord and spinal column tumors: principles and practice. New York: Thieme; 2006:404-419.

39. York J.E., Berk R.H., Fuller G.N., et al. Chondrosarcoma of the spine: 1954 to 1997. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(Suppl 1):73-78.

40. Venkateswaran L., Rodriguez-Galindo C., Merchant T.E., et al. Primary Ewing tumor of the vertebrae: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors and outcome. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37(1):30-35.

41. Althausen P.L., Schneider P.D., Bold R.J., et al. Multimodality management of a giant cell tumor arising in the proximal sacrum: case report. Spine. 2002;27(15):E361-E365.

42. Turcotte R.E., Sim F.H., Unni K.K. Giant cell tumor of the sacrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;291:215-221.

43. Verhagen W.I., Bartels R.H., Schaafsma H.E., Rob de Jong T.H. A giant cell tumor of the sacrum or a soft tissue giant cell tumor? A case report. Spine. 1998;23(14):1609-1611.

44. Bennett C.J.Jr., Marcus R.B.Jr., Million R.R., Enneking W.F. Radiation therapy for giant cell tumors of bone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;26(2):299-304.

45. Gokaslan Z.L., Romsdahl M.M., Kroll S.S., et al. Total sacrectomy and Galveston L-rod reconstruction for malignant neoplasms. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1997;87(5):781-787.

46. Marcove R.C., Sheth D.S., Brien E.W., et al. Conservative surgery for giant cell tumors of the sacrum. The role of cryosurgery as a supplement to curettage and partial excision. Cancer. 1994;74(4):1253-1260.

47. Ozaki T., Liljenqvist U., Halm H., et al. Giant cell tumor of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;401:194-201.

48. Abernathey C.D., Onofrio B.M., Scheithauer B., et al. Surgical management of giant sacral schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 1986;65(3):286-295.

49. Fourney D.R., Gokaslan Z.L. Surgical approaches for the resection of sacral tumors. In: Fehlings M., Dickman C.A., Gokaslan Z.L., editors. Spinal cord and spinal column tumors: principles and practice. New York: Thieme,; 2006:632-648.

50. MacCarty C.S., Waugh J.M., Mayo C.W., Coventry M.D. The surgical treatment of presacral tumors: a combined problem. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1952;27:73-84.

51. Bowers R. Giant cell tumor of the sacrum: a case report. Ann Surg. 1948;128(6):1164-1172.

52. Localio S.A., Eng K., Ranson J.H. Abdominosacral approach for retrorectal tumors. Ann Surg. 1980;191(5):555-560.

53. Simpson A.H., Porter A., Davis A., et al. Cephalad sacral resection with a combined extended ilioinguinal and posterior approach. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77(3):405-411.

54. Stener B., Gunterberg B. High amputation of the sacrum for extirpation of tumors. Principles and technique. Spine. 1978;3(4):351-366.

55. Skene A.I., Gault D.T., Woodhouse C.R., et al. Perineal, vulval and vaginoperineal reconstruction using the rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. Br J Surg. 1990;77(6):635-637.

56. Tobin G.R., Day T.G. Vaginal and pelvic reconstruction with distally based rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81(1):62-73.

57. Alper M., Bilkay U., Keçeci Y., et al. Transsacral usage of a pure island TRAM flap for a large sacral defect: a case report. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44(4):417-421.

58. Cahill D. Surgical approaches to the lumbar spine and sacrum. In: Rea G., editor. Spine tumors. Rolling Meadows: American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 1994.

59. Miles W.K., Chang D.W., Kroll S.S., et al. Reconstruction of large sacral defects following total sacrectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2387-2394.

60. Dahlin D.C., Cupps R.E., Johnson E.W.Jr. Giant-cell tumor: a study of 195 cases. Cancer. 1970;25(5):1061-1070.

61. Tomita K., Tsuchiya H. Total sacrectomy and reconstruction for huge sacral tumors. Spine. 1990;15(11):1223-1227.

62. Zhang H.Y., Thongtrangan I., Balabhadra R.S., et al. Surgical techniques for total sacrectomy and spinopelvic reconstruction. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(2):E5.

63. Sugarbaker P. Partial sacrectomy for en bloc excision of rectal cancer with posterior fixation. Dis Colon Rect. 1982;25(7):708-711.

64. Temple W.J., Ketcham A.S. Sacral resection for control of pelvic tumors. Am J Surg. 1992;163(4):370-374.

65. Gunterberg B., Romanus B., Stener B. Pelvic strength after major amputation of the sacrum. An experimental study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47(6):635-642.

66. Beadel G.P., McLaughlin C.E., Aljassir F., et al. Iliosacral resection for primary bone tumors: is pelvic reconstruction necessary? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:22-29.

67. Allen B.L.Jr., Ferguson R.L. The Galveston technique for L rod instrumentation of the scoliotic spine. Spine. 1982;7(3):276-284.

68. Wuisman P., Lieshout O., Sugihara S., van Dijk M. Total sacrectomy and reconstruction: oncologic and functional outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;381:192-203.

69. Guyton J. Fractures of hip, acetabulum, and pelvis. Canale S., editor. Campbell’s operative orthopedics, ed 9, vol 3. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

70. Freeman B.III. Scoliosis and kyphosis. Canale S., editor. Campbell’s operative orthopedics, ed 9, vol 3. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

71. Norris B.L., Busse M.J., Kellam J.F., et al. Pelvic fractures: sacral fixation. Wiss D., editor. Fractures. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998:613-629.

73. Wuisman P., Liseshout O., van Dijk M., van Diest P. Reconstruction after total en bloc sacrectomy for osteosarcoma using a custom-made prosthesis: a technical note. Spine. 2001;26(4):431-439.

74. Carlson G.D., Abitbol J.J., Anderson D.R., et al. Screw fixation in the human sacrum. An in vitro study of the biomechanics of fixation. Spine. 1992;17(Suppl 6):S196-S203.

75. Carson W.L., Duffield R.C., Arendt M., et al. Internal forces and moments in transpedicular spine instrumentation. The effect of pedicle screw angle and transfixation: the 4R-4bar linkage concept. Spine. 1990;15(9):893-901.

76. Biagini R., Ruggieri P., Mercuri M., et al. Neurologic deficit after resection of the sacrum. Chir Organi. 1997;82(4):357-372.

77. Guo Y., Palmer J.L., Shen L., et al. Bowel and bladder continence, wound healing, and functional outcomes in patients who underwent sacrectomy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3(2):106-110.

78. Todd L.T.Jr., Yaszemski M.J., Currier B.L., et al. Bowel and bladder function after major sacral resection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;397:36-39.

79. Sung H.W., Shu W.P., Wang H.M., et al. Surgical treatment of primary tumors of the sacrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;215:91-98.

80. Touran T., Frost D.B., O’Connell T.X. Sacral resection. Operative techniques and outcome. Arch Surg. 1990;125(7):9110-9113.

81. Gottfried O.N., Schmidt M.H., Stevens E.A. Embolization of sacral tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(2):E4.