Chapter 21 Rumination, Pica, and Elimination (Enuresis, Encopresis) Disorders

21.2 Pica

Epidemiology

Pica appears to be more common in children with mental retardation, pervasive developmental disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and other neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., Kleine-Levin syndrome, schizophrenia). It usually remits in childhood but can continue into adolescence and adulthood. Geophagia (eating earth) is associated with pregnancy and is not seen as abnormal in some cultures (e.g., rural or preindustrial societies in parts of Africa and India). Children with pica are at increased risk for lead poisoning (Chapter 702), iron-deficiency anemia (Chapter 449), obstruction, dental injury, and parasitic infections.

Treatment

A combined medical and psychosocial approach is generally indicated for pica. The sequelae related to the ingested item can require specific treatment (e.g., lead toxicity, iron-deficiency anemia, parasitic infestation). Ingestion of hair can require medical or surgical intervention for a gastric bezoar (Chapter 326). Nutritional education, cultural factors, psychologic assessment, and behavior interventions are important in developing an intervention strategy for this disorder.

21.3 Enuresis (Bed-Wetting)

Etiology

Children with nocturnal enuresis might hyposecrete arginine vasopressin (AVP) and may be less responsive to the lower urine osmolality associated with fluid loading. Many affected children also appear to have small functional bladder capacity. There is some support for a relationship among sleep architecture, diminished capacity to be aroused from sleep, and abnormal bladder function. A subgroup of patients with enuresis has been identified in whom there is no arousal to bladder distention and an unusual pattern of uninhibited bladder contractions before the enuretic episode. One specific sleep disorder, sleep apnea, has been associated with enuresis (Chapter 17). Although the mechanism is unknown, central nervous system immaturity with delays in motor and language milestones appears to be a relevant etiology of enuresis for some children.

Treatment

The treatment of monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis should be marked by a conservative, gentle, and patient approach. Treatment can begin with parent-child education, charting with rewards for dry nights, voiding before bedtime, and night awakening 2-4 hr after bedtime, while at the same time making sure that parents do not punish the child for enuretic episodes (Table 21-1). In addition, the child should be encouraged to avoid holding urine and to void frequently during the day (to avoid day wetting). These children also need ready access to school toilets. Furthermore, if constipation and fecal impaction are problems (Chapter 22.4), children should be encouraged to have a daily bowel movement and taught optimal relaxation of pelvic floor muscles to improve bowel emptying.

Table 21-1 TREATMENT REGIMEN FOR MONOSYMPTOMATIC NOCTURNAL ENURESIS

From Chandra MM: Enuresis and voiding dysfunction. In Burg FD, Ingelfinger JR, Polin RA, et al, editors: Current pediatric therapy, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 591.

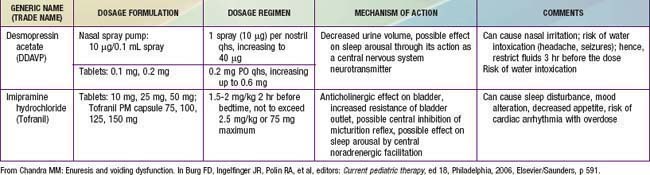

Pharmacotherapy for nocturnal enuresis is second-line treatment (Table 21-2). Desmopressin acetate (DDAVP) is a synthetic analog of the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) vasopressin, which decreases nighttime urine production. The fast action of DDAVP suggests a role for special occasions (e.g., sleepovers), when rapid control of bedwetting is desired. Unfortunately, the relapse rate is high when DDAVP is discontinued. DDAVP is also associated with rare side effects of hyponatremia and water intoxication, with resulting seizures. Although imipramine has some usefulness, less than 50% of children respond, and most relapse when the medication is discontinued. Bothersome side effects and potential lethality in overdose also limit this medication’s usefulness. Much less commonly used, oxybutynin and tolterodine are antimuscarinic drugs, which may be effective by reducing bladder spasm and increasing bladder capacity.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with enuresis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1540-1550.

Butler RJ, Heron J. The prevalence of infrequent bedwetting and nocturnal enuresis in childhood. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42:257-264.

Humphreys M, Reinberg Y. Contemporary and emerging drug treatments for urinary incontinence in children. Pediatric Drugs. 2005;7:151-162.

Jackson EC. Is lack of bladder inhibition during sleep a mechanism of nocturnal enuresis? J Pediatr. 2007;151:559-560.

Lane W, Robson M. Evaluation and management of enuresis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1429-1436.

Rocha MM, Costa NK, Silvares EF. Changes in parents’ and self-reports of behavioral problems in Brazilian adolescents after behavioral treatment with urine alarm for nocturnal enuresis. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34:749-757.

Schulz-Juergensen S, Rieger M, Schaeffer J, et al. Effect of 1-desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin on prepulse inhibition of startle supports a central etiology of primary monosymptomatic enuresis. J Pediatr. 2007;151:571-574.

Wang QW, Wen JG, Zhang RL, et al. Family and segregation studies: 411 Chinese children with primary nocturnal enuresis. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:618-622.

21.4 Encopresis

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The first priority in evaluating a child with fecal incontinence is to rule out a general medical condition (e.g., tethered cord, Chapter 598.1) causing the problem. The presence of fecal retention should then be determined. A positive finding on rectal examination is sufficient to document fecal retention, but a negative finding requires plain abdominal films (Fig. 21-1). Additional diagnostic studies are rarely indicated.

Treatment

The standard medical treatment of retentive encopresis involves the clearance of impacted fecal material followed by the short-term use of mineral oil or laxatives to prevent further constipation (Tables 21-3 and 21-4). There needs to be a focus on adherence with regular postprandial toilet sitting and adoption of a balanced diet. Once impacted stool is removed, the combination of constipation management and simple behavior therapy is successful in the majority of cases, although it is often a period of months before soiling stops completely. Compliance can wane, and failure of this standard treatment approach sometimes requires more intensive intervention, with a special emphasis on adherence to a high-fiber diet and family support for behavioral change. Keeping records of the child’s progress is necessary. In cases where behavioral or psychiatric problems are evident, group or individual psychotherapy may be necessary.

Table 21-3 SUGGESTED MEDICATIONS AND DOSAGES FOR DISIMPACTION

| MEDICATION | AGE | DOSAGE |

|---|---|---|

| RAPID RECTAL DISIMPACTION | ||

| Glycerin suppositories | Infants and toddlers | |

| Phosphate enema | <1 yr | 60 mL |

| >1 yr | 6 mL/kg bodyweight, up to 135 mL twice | |

| Milk of molasses enema | Older children | (1 : 1 milk : molasses) 200-600 mL |

| SLOW ORAL DISIMPACTION IN OLDER CHILDREN | ||

| Over 2-3 Days | ||

| Polyethylene glycol with electrolytes | 25 mL/kg bodyweight/hr, up to 1000 mL/h until clear fluid comes from the anus | |

| Over 5-7 Days | ||

| Polyethylene without electrolytes | 1.5 g/kg bodyweight per day for 3 days | |

| Milk of magnesia | 2 mL/kg bodyweight twice/day for 7 days | |

| Mineral oil | 3 mL/kg bodyweight twice/day for 7 days | |

| Lactulose or sorbitol | 2 mL/kg bodyweight twice/day for 7 days | |

From Loening-Baucke V: Functional constipation with encopresis. In Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 183.

Table 21-4 SUGGESTED MEDICATIONS AND DOSAGES FOR MAINTENANCE THERAPY OF CONSTIPATION

| MEDICATION | AGE | DOSE |

|---|---|---|

| FOR LONG-TERM TREATMENT (YEARS): | ||

| Milk of magnesia | >1 mo | 1-3 mL/kg body weight/day, divide in 1-2 doses |

| Mineral oil | >12 mo | 1-3 mL/kg body weight/day, divided in 1-2 doses |

| Lactulose or sorbitol | >1 mo | 1-3 mL/kg body weight/day, divide in 1-2 doses |

| Polyethylene glycol 3350 (MiraLax) | >1 mo | 0.7 g/kg body weight/day, divide in 1-2 doses |

| FOR SHORT-TERM TREATMENT (MONTHS): | ||

| Senna (Senokot) syrup, tablets | 1-5 yr | 5 mL (1 tablet) with breakfast, max 15 mL daily |

| 5-15 yr | 2 tablets with breakfast, maximum 3 tablets daily | |

| Glycerin enemas | >10 yr | 20-30 mL/day (1/2 glycerin and 1/2 normal saline) |

| Bisacodyl suppositories | >10 yr | 10 mg daily |

From Loening-Baucke V: Functional constipation with encopresis. In Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 185.

Boners ME, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Functional nonretentive fecal incontinence in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:5-13.

Reid H, Bahar RJ. Treatment of encopresis and chronic constipation in young children: clinical results from interactive parent-child guidance. Clin Pediatr. 2006;45:157-164.

Voskuijl WP, Reitsma JB, van Ginkel R, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of children with functional nonretentive fecal incontinence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:67-72.