Chapter 239 Rubella

Epidemiology

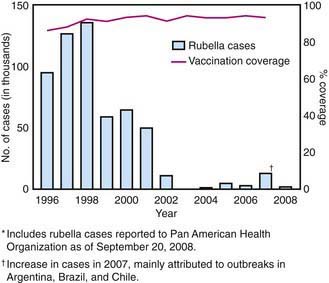

In the prevaccine era, rubella appeared to occur in major epidemics every 6-9 yr, with smaller peaks interspersed every 3-4 yr, and was most common in preschool and school-aged children. Following introduction of the rubella vaccine, the incidence fell by >99%, with a relatively higher percentage of infections reported among persons >19 yr of age. After years of decline, a resurgence of rubella and CRS occurred during 1989-1991 (Fig. 239-1). Subsequently, a 2-dose recommendation for rubella vaccine was implemented and resulted in a decrease in incidence of rubella from 0.45/100,000 in 1990 to 0.1/100,000 in 1999 and a corresponding decrease of CRS, with an average of 6 infants with CRS reported annually from 1992 to 2004. Mothers of these infants tended to be young, Hispanic, or foreign born. The number of reported cases of rubella continued to decline in the early part of this decade.

Pathology

Little information is available on the pathologic findings in rubella occurring postnatally. The few reported studies of biopsy or autopsy material from cases of rubella revealed only nonspecific findings of lymphoreticular inflammation and mononuclear perivascular and meningeal infiltration. The pathologic findings for CRS are often severe and may involve nearly every organ system (Table 239-1).

Table 239-1 PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS IN CONGENITAL RUBELLA SYNDROME

| SYSTEM | PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| Pulmonary artery stenosis | |

| Ventriculoseptal defect | |

| Myocarditis | |

| Central nervous system | Chronic meningitis |

| Parenchymal necrosis | |

| Vasculitis with calcification | |

| Eye | Microphthalmia |

| Cataract | |

| Iridocyclitis | |

| Ciliary body necrosis | |

| Glaucoma | |

| Retinopathy | |

| Ear | Cochlear hemorrhage |

| Endothelial necrosis | |

| Lung | Chronic mononuclear interstitial pneumonitis |

| Liver | Hepatic giant cell transformation |

| Fibrosis | |

| Lobular disarray | |

| Bile stasis | |

| Kidney | Interstitial nephritis |

| Adrenal gland | Cortical cytomegaly |

| Bone | Malformed osteoid |

| Poor mineralization of osteoid | |

| Thinning cartilage | |

| Spleen, lymph node | Extramedullary hematopoiesis |

| Thymus | Histiocytic reaction |

| Absence of germinal centers | |

| Skin | Erythropoiesis in dermis |

Pathogenesis

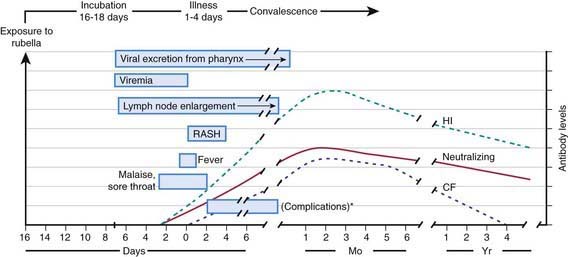

The viral mechanisms for cell injury and death in rubella are not well understood for either postnatal or congenital infection. Following infection, the virus replicates in the respiratory epithelium, then spreads to regional lymph nodes (Fig. 239-2). Viremia ensues and is most intense from 10 to 17 days after infection. Viral shedding from the nasopharynx begins about 10 days after infection and may be detected up to 2 wk following onset of the rash. The period of highest communicability is from 5 days before to 6 days after the appearance of the rash.

Clinical Manifestations

Postnatal infection with rubella is a mild disease not easily discernible from other viral infections, especially in children. Following an incubation period of 14-21 days, a prodrome consisting of low-grade fever, sore throat, red eyes with or without eye pain, headache, malaise, anorexia, and lymphadenopathy begins. Suboccipital, postauricular, and anterior cervical lymph nodes are most prominent. In children, the 1st manifestation of rubella is usually the rash, which is variable and not distinctive. It begins on the face and neck as small, irregular pink macules that coalesce, and it spreads centrifugally to involve the torso and extremities, where it tends to occur as discrete macules (Fig. 239-3). About the time of onset of the rash, examination of the oropharynx may reveal tiny, rose-colored lesions (Forchheimer spots) or petechial hemorrhages on the soft palate. The rash fades from the face as it extends to the rest of the body so that the whole body may not be involved at any 1 time. The duration of the rash is generally 3 days, and it usually resolves without desquamation. Subclinical infections are common, and 25-40% of children may not have a rash.

Laboratory Findings

Leukopenia, neutropenia, and mild thrombocytopenia have been described during postnatal rubella.

Complications

Progressive rubella panencephalitis (PRP) is an extremely rare complication of either acquired rubella or CRS. It has an onset and course similar to those of the subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) associated with measles (Chapter 238). Unlike in the postinfectious form of rubella encephalitis, however, rubella virus may be isolated from brain tissue of the patient with PRP, suggesting an infectious pathogenesis, albeit a “slow” one. The clinical findings and course are undistinguishable from those of SSPE and transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (Chapter 270). Death occurs 2-5 yr after onset.

Congenital Rubella Syndrome

In 1941 an ophthalmologist first described a syndrome of cataracts and congenital heart disease that he correctly associated with rubella infections in the mothers during early pregnancy (Table 239-2). Shortly after the first description, hearing loss was recognized as a common finding often associated with microcephaly. In 1964-1965 a pandemic of rubella occurred, with 20,000 cases reported in the USA leading to >11,000 spontaneous or therapeutic abortions and 2,100 neonatal deaths. From this experience emerged the expanded definition of CRS that included numerous other transient or permanent abnormalities.

Table 239-2 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CONGENITAL RUBELLA SYNDROME IN 376 CHILDREN FOLLOWING MATERNAL RUBELLA*

| MANIFESTATION | RATE (%) |

|---|---|

| Deafness | 67 |

| Ocular | 71 |

| Cataracts | 29 |

| Retinopathy | 39 |

| Heart disease† | 48 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 78 |

| Right pulmonary artery stenosis | 70 |

| Left pulmonary artery stenosis | 56 |

| Valvular pulmonic stenosis | 40 |

| Low birthweight | 60 |

| Psychomotor retardation | 45 |

| Neonatal purpura | 23 |

| Death | 35 |

* Other findings: hepatitis, linear streaking of bone, hazy cornea, congenital glaucoma, delayed growth.

† Findings in 87 patients with congenital rubella syndrome and heart disease who underwent cardiac angiography.

From Cooper LZ, Ziring PR, Ockerse AB, et al: Rubella: clinical manifestations and management, Am J Dis Child 118:18–29, 1969.

Nerve deafness is the single most common finding among infants with CRS. Most infants have some degree of intrauterine growth restriction. Retinal findings described as salt-and-pepper retinopathy are the most common ocular abnormality but have little early effect on vision. Unilateral or bilateral cataracts are the most serious eye finding, occurring in about a third of infants (Fig. 239-4). Cardiac abnormalities occur in half of the children infected during the 1st 8 wk of gestation. Patent ductus arteriosus is the most frequently reported cardiac defect, followed by lesions of the pulmonary arteries and valvular disease. Interstitial pneumonitis leading to death in some cases has been reported. Neurologic abnormalities are common and may progress following birth. Meningoencephalitis is present in 10-20% of infants with CRS and may persist for up to 12 mo. Longitudinal follow-up through 9-12 yr of infants without initial retardation revealed progressive development of additional sensory, motor, and behavioral abnormalities, including hearing loss and autism. PRP has also been recognized rarely after CRS. Subsequent postnatal growth retardation and ultimate short stature have been reported in a minority of cases. Rare reports of immunologic deficiency syndromes have also been described.

Vaccination

Rubella vaccine in the USA consists of the attenuated RA 27/3 strain that is usually administered in combination with measles and mumps (MMR) or also with varicella (MMRV) in a 2-dose regimen at 12-15 mo and 4-6 yr of age. It theoretically may be effective as postexposure prophylaxis if administered within 3 days of exposure. Vaccine should not be administered to severely immunocompromised patients (e.g., transplant recipients). Patients with HIV infection who are not severely immunocompromised may benefit from vaccination. Fever is not a contraindication, but if a more serious illness is suspected, immunization should be delayed. Immune globulin preparations may inhibit the serologic response to the vaccine (Chapter 165). Vaccine should not be administered during pregnancy. If pregnancy occurs within 28 days of immunization, the patient should be counseled on the theoretical risks to the fetus. Studies of >200 women who had been inadvertently immunized with rubella vaccine during pregnancy showed that none of their offspring developed CRS. Therefore, interruption of pregnancy is probably not warranted.

Banatvala JE, Brown DWG. Rubella. Lancet. 2004;363:1127-1137.

Bloom S, Rguig A, Berraho A, et al. Congenital rubella syndrome burden in Morocco: a rapid retrospective assessment. Lancet. 2005;365:135-140.

Bullens D, Koenraad S, Vanhaesebrouck P. Congenital rubella syndrome after maternal reinfection. Clin Pediatr. 2000;39:113-116.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward control of rubella and prevention of congenital rubella syndrome—worldwide, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59(40):1307-1310.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome—the Americas, 2003–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1176-1179.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rubella vaccination during pregnancy—United States, 1971–1988. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38:289-292.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health: elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome—United States, 1969–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:279-282.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Brief report: imported case of congenital rubella syndrome—New Hampshire, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:1160-1161.

Cooper LZ, Ziring PR, Ockerse AB, et al. Rubella: clinical manifestations and management. Am J Dis Child. 1969;118:18-29.

Corcoran C, Hardie DR. Serologic diagnosis of congenital rubella: a cautionary tale. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:286-287.

Dwyer DE, Robertson PW, Field PR. Clinical and laboratory features of rubella. Pathology. 2001;33:322-328.

Frey RK. Neurological aspects of rubella virus infection. Intervirology. 1997;40:167-175.

Hahne S, Macey J, van Binnendijk R, et al. Rubella outbreak in the Netherlands, 2004–2005. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:795-800.

McIntosh ED, Menser MA. A fifty-year follow-up of congenital rubella. Lancet. 1992;340:414-415.

Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Pollock TM. Consequences of confirmed maternal rubella at successive stages of pregnancy. Lancet. 1982;2:781-784.

Townsend JJ, Stroop WG, Baringer JR, et al. Neuropathology of progressive rubella panencephalitis after childhood rubella. Neurology. 1982;32:185-190.