Rubella and Rubeola Infections

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Describe the etiology and epidemiology of rubella (German measles) infection.

• Explain the signs and symptoms of acquired and congenital rubella infection.

• Compare the immunologic manifestations of acquired and congenital rubella infection.

• Explain the laboratory diagnostic evaluation of rubella infection.

• Summarize the epidemiology and laboratory diagnosis of rubeola (measles).

• Analyze a representative case study.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the principle, results, limitations, and clinical applications of the passive latex agglutination test for Rubella.

Rubella

Etiology of Rubella

Signs and Symptoms of Rubella Infection

Acquired Rubella Infection

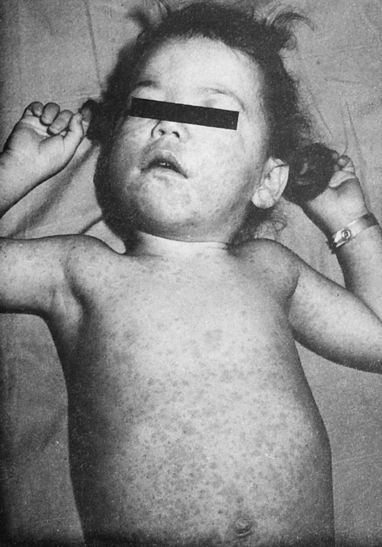

The clinical presentation of acquired rubella is usually mild. The clinical manifestations of infection usually begin with a prodromal period of catarrhal symptoms, followed by involvement of the retroauricular, posterior cervical, and postoccipital lymph nodes, and finally by the emergence of a maculopapular rash on the face and then on the neck and trunk (Figs. 24-1 and 24-2). A temperature less than 34.4° C (94° F) is usually present. In older children and adults, self-limiting arthralgia and arthritis are common.

Congenital Rubella Infection

Rubella infection is usually a mild, self-limiting disease with only rare complications in children and adults. In pregnant women, however, especially those infected in the first trimester, rubella can have devastating effects on the fetus (Fig. 24-3). In utero infection can result in fetal death or manifest as rubella syndrome, a spectrum of congenital defects. About 10% to 20% of infants infected in utero fail to survive beyond 18 months.

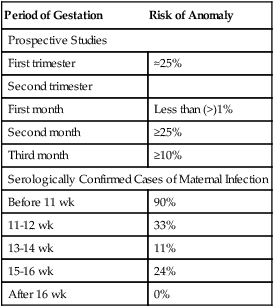

The point in the gestation cycle at which maternal rubella infection occurs greatly influences the severity of congenital rubella syndrome (Table 24-1); the extent of congenital anomalies varies from one infant to another. Some infants manifest almost all the defects associated with rubella, whereas others exhibit few, if any, consequences of infection. Clinical evidence of congenital rubella infection may not be recognized for months or even years after birth.

Table 24-1

Manifestation of Anomalies in Maternal Rubella

| Period of Gestation | Risk of Anomaly |

| Prospective Studies | |

| First trimester | ≈25% |

| Second trimester | |

| First month | Less than (>)1% |

| Second month | ≥25% |

| Third month | ≥10% |

| Serologically Confirmed Cases of Maternal Infection | |

| Before 11 wk | 90% |

| 11-12 wk | 33% |

| 13-14 wk | 11% |

| 15-16 wk | 24% |

| After 16 wk | 0% |

Diagnostic Evaluation

Several screening methods are available, including the TORCH (Toxoplasma, other [viruses], rubella, cytomegalovirus [CMV], and herpes) procedure (see Chapter 15). The assays for the determination of immune status and evidence of recent infection are presented in Table 24-2.

Table 24-2

| Method | Antibody Detected |

| TORCH antibodies | IgM |

| TORCH antibodies | IgG |

| Chemiluminescent immunoassay | IgM |

| Chemiluminescent Immunoassay | IgG |

| Immunochromatographic assay | IgG |

| Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) | Monoclonal antibody (antibodies) to rubella virus virion proteins, E2 and C |

Rubeola (Measles)

Rubella and Rubeola are two distinctly different infections. Rubeola is referred to as measles.

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by the rubeola virus.

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory confirmation of measles is made by the detection measles-specific immunoglobulin M antibodies in serum of, isolation of measles virus, or detection of measles virus RNA by nucleic acid amplification in an appropriate clinical specimen (e.g., nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs, nasal aspirates, throat washes, or urine; Table 24-3).

Table 24-3

Measles (Rubeola) Antibody Testing

| Test Name | Recommended Use | Comments |

| Viral culture method—cell culture, immunofluorescence | Gold standard procedure | Nasopharyngeal aspirate, washing, throat swab, lung tissue, CSF or urine samples |

| Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | Measles (rubeola) antibody IgG and IgM; semiquantitative Measles (rubeola) antibody, IgG; semiquantitative Measles (rubeola) antibody, IgM or IgG, CSF; semiquantitative |

Low IgM antibody levels occasionally persist >12 mo postinfection or immunization ; residual IgM response may be distinguished from early IgM response by testing patient sera 2-3 wk later for changes in specific IgM antibody levels. Screen for vaccination responses. Diagnose rare but fatal subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) in CSF samples; rubeola CSF antibody detection may indicate central nervous system infection; possible contamination by blood or transfer of serum antibodies across blood-brain barrier can affect the results. |

Adapted from ARUP Laboratories: Measles virus—rubeola, 2012 (http://www.arupconsult.com/Topics/Rubeola.html).

Serum testing for antibodies is done for the following reasons:

• Can confirm acute infection with measles using IgM and IgG serial testing

• Can confirm seroconversion after vaccination using IgG testing

• IgM and IgG cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing to identify subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, which may occur years after the original infection using IgG testing

• Nasopharyngeal and blood cultures—most sensitive if collected during prodrome up to 1 to 2 days after onset of rash

• Virus can be isolated from urine culture up to 1 week or more after onset of rash

Chapter Highlights

• Acquired rubella (German or 3-day measles) is caused by an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus of the Togaviridae family. It is endemic to human beings, highly contagious, and transmitted through respiratory secretions.

• Contracting rubella infection and vaccinating against rubella are the only ways to develop immunity.

• A diagnosis of acquired rubella is not based solely on clinical manifestations; signs and symptoms vary widely. Although usually mild and self-limiting, with rare complications in children and adults, rubella infections in pregnant women, especially in the first trimester, can result in fetal death or congenital rubella syndrome.

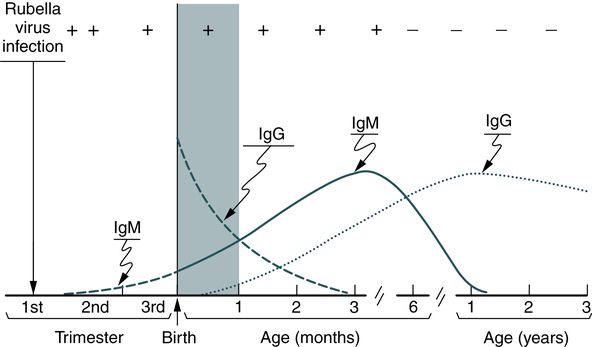

• In primary rubella infection, the appearance of IgG and IgM antibodies is associated with clinical signs and symptoms, when present. IgM antibodies are detectable a few days after onset of symptoms, reach peak levels at 7 to 10 days, and persist but decrease rapidly in concentration over the next 4 to 5 weeks, until no longer clinically detectable.

• IgM antibody in a single specimen suggests a recent rubella infection.

• An unequivocal increase in IgG antibody concentration between the acute and convalescent specimens suggests a recent primary infection or an anamnestic antibody response to rubella in an immune individual.

• Negative IgM and IgG test results indicate that the patient has never had rubella infection or been vaccinated. These patients are susceptible to infection. If no IgM is demonstrable but IgG is present in paired specimens, the patient is immune.

• IgM does not cross an intact placental barrier, so its demonstration in a single neonatal specimen is diagnostic of congenital rubella syndrome. Rubella infection can be confirmed serologically by IgM antibody testing for at least the first 6 months of life, especially when clinical evidence of congenital rubella is slow in emerging or has an uncertain origin.

• Laboratory confirmation of (rubeola) measles is made by the detection of measles-specific immunoglobulin M antibodies in serum, isolation of measles virus, or detection of measles virus RNA by nucleic acid amplification in an appropriate clinical specimen.