Chapter 5 Rotation Flaps

Most surgical wounds can be closed either linearly or by tissue advancement. With linear closure and with advancement, all tension is directed along a single vector. Wounds that are too tight to close in one direction can frequently be repaired by redirecting tension away from the primary motion. Rotation is the simplest method of recruiting laxity from multiple directions to allow for the closure of an operative wound, and the redirection of wound closure tension is the primary purpose of a rotation flap.1 The design of a traditional rotation flap utilizes a curvilinear incision along an arc adjacent to the primary surgical defect. As a rotation flap is executed, the direction of wound closure tension is effectively changed. A rotation flap converts the existing primary surgical defect into a secondary defect that can be more appropriately located and more easily closed. Laxity of the adjacent tissue allows the flap to be rotated into the primary defect and the tension vector is reoriented in the direction of the secondary defect or secondary motion of the flap. Rotation flaps also frequently allow for displacement of dog-ears to more favorable locations. Well-designed rotation flaps create scar lines that are hidden along facial boundaries or within relaxed skin tension lines. There are few repairs as elegant and seemingly simplistic as a well-designed and well-executed rotation flap. In practice, flaps that utilize only rotational motion are uncommon, and a simplistically designed rotation flap rarely suitably repairs an operative defect. Most rotation flaps actually combine several different types of motion, and most incorporate significant degrees of tissue advancement.

ROTATION FLAP DESIGN: BASIC PRINCIPLES

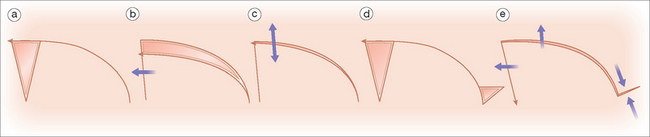

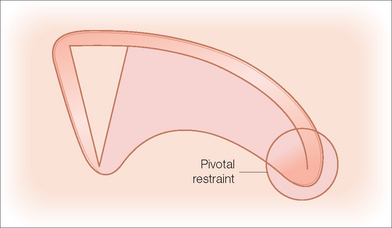

The classic rotation flap incorporates a triangulated defect and a smooth curvilinear flap sweep. Like all flaps, rotation flaps are hindered in their movements by the inherent stiffness of the tissue at the flaps’ pivot points. Because of this pivotal restraint, even with proper flap sizing, the tip of the rotation flap will not extend to the distal margin of the operative defect unless the tip of the flap is also advanced under some tension. That is, if the flap is elevated and the primary defect is closed under no tension, the tip of the rotation falls short of the distal extent of the operative wound. In order to close the entire primary wound and also the secondary defect, it is necessary to advance the flap tip and the curve of the flap in order to close the secondary operative wound (Figure 5.1). If the surrounding tissue is mobile, this secondary motion must be considered in order to avoid unwanted displacement of adjacent structures. If the surrounding tissue is immobile, tension must be placed on the flap tip in order to achieve closure. In order to minimize tension on the flap tip and eliminate the need for undesirable secondary motion around the operative defect, the arc of the rotation can be oversized and offset so that the arc of the flap extends vertically beyond the distal extent of the operative defect.2,3 The radius of the flap must be large enough so that the on rotation, the leading edge of the flap extends beyond the distal edge of the defect. The reason for extending the flap tip is to reduce tension and enable the flap to rotate into place without forcibly advancing the tip. This prevents undesirable tension and possible tissue ischemia at the flap’s most vulnerable point, its tip. When the flap’s rotation is subsequently executed, the extended tip of the flap then rests without tension where it meets the distant point of the primary defect (Figure 5.2). This concept has been previously eloquently reviewed, and the concept of extending the rotation arc beyond the end of an operative wound has been firmly entrenched in the reconstructive literature.

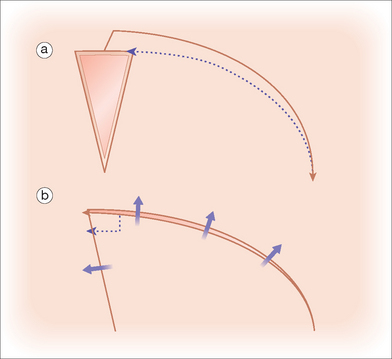

A rotation flap can frequently be closed without undermining beneath the point of pivotal restraint; however, for optimal flap motion, this area of restraint should be undermined (Figure 5.3). This is particularly important with the dorsal nasal flap, where maximal rotation is required to close a defect located in the inelastic skin of the distal nose. Proper undermining of the pivot point accomplishes the release of deep restraint and usually allows substantial motion of the flap. This undermining is not without some risk, as too much undermining may interfere with deep vascular perforators. However, the reduction in tension on the flap tip usually more than compensates for any diminishment in pedicle vascularity.

Occasionally, a back cut into the rotation flap’s body can improve flap mobility, particularly on relatively immobile skin such as on the scalp.4 A back cut frees both deep and lateral restraint and can prove valuable in reducing closure tension, but a back cut also has the potential to compromise the vascular supply of the flap’s pedicle. The more ample the residual vascular input, the more extensive of a back cut may be created. If, as in the case of the dorsal nasal flap, the remaining pedicle contains large caliber axial vessels, the width of the pedicle may be safely narrowed and a substantial back cut will be tolerated. The defect from a back cut is usually closed with a V-to-Y repair, trimming excess tissue from the apex of the flap as indicated. Alternately, as in the original Reiger flap, the apex may be closed with a Z-plasty.8

Flap length

The appropriate design of a rotation flap often involves the creation of long incision lines. If a rotation flap with a very short arc is designed, the width of the secondary defect created upon flap rotation will be proportionally larger, and the potentials for unacceptable secondary motion and inappropriately high wound closure tensions are magnified. A longer arc of flap rotation allows easier closure of the narrowed secondary defect, and the likelihood for flap survival is increased because of the minimization of wound closure tensions.5 In addition, a longer rotation flap allows for easier redistribution of tissue redundancy along the longer outer arc of rotation. Thus, the incision lines for rotation flaps typically need to be longer than one would initially expect if the flap is to be placed under minimal tension and if unwanted displacement of structures surrounding the primary defect is to be avoided.

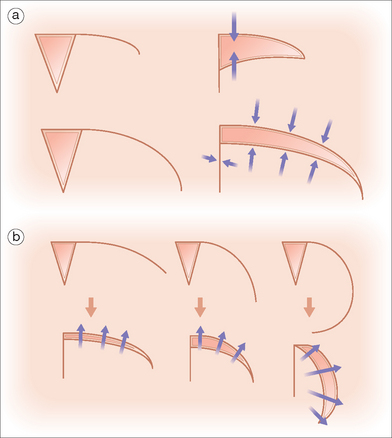

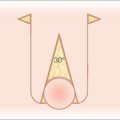

Flap curvature

Most rotation flaps are designed with an arc that transects about one quarter of a circle. Such a flap design reliably redistributes tension vectors along the secondary operative defect. Rotation is limited by the surface restraint of the pivot point. The greater the curvature of a flap, the greater degree of rotation can be accomplished. Similar to a back cut, a greater curvature actually cuts into the pedicle and permits greater freedom of movement by freeing pivotal restraint. However, too great of an arc of rotation will actually redirect tension “backward” and may negate the decrease in tension that the rotation flap was supposed to accomplish (Figure 5.4).

Because rotation flaps require long incision lines to achieve appropriate flap motion, in many facial locations, there are often other flap repairs that are more palatable. Rotation flaps have their greatest utility in the closure of scalp, temple, and cheek defects. In select cases, rotation flaps are also quite valuable on the nose. On the scalp, a lack of adjacent skin mobility requires rotation flaps to be especially long in order to close even small to moderate-sized operative wounds. On the cheek, rotation flaps are particularly useful for the repair of medially located wounds, because the rotation flap can effectively mobilize the large reservoir of loose skin in the entire area of the lateral cheek.6 Infraorbital wounds can be closed with rotation flaps that recruit substantial laxity from the temple. Because rotation flaps tend to be rather “short” flaps when the distance from the flap base to the tip is considered, their vascular supply is quite predictable, and ischemic failures of the flaps are very uncommon if the flaps are handled gently and closed under minimal tension.

BILATERAL ROTATION FLAPS

Bilateral or dual rotation flaps utilize rotation from two sides of an operative defect to allow for wound closure where motion from one side would either be inadequate to close the wound or where symmetry of the repair is desired for enhanced cosmesis. Bilateral rotation flaps are most useful for large forehead wounds where a bicoronal incision is utilized (Figure 5.5) or for chin defects where the arc of the bilateral rotation lies within the mental crease.

O–Z Rotation Flap

The construction of an O–Z flap involves the creation of opposing rotation flaps, one of which takes origin from one side of the operative wound and the other as a mirror image from the opposing side of the defect. In the design of the O–Z flap, however, there is great flexibility. The paired flaps can be designed to rely upon pure rotational movement, or there can be varying amounts of flap advancement introduced into the operative design. The surgeon should appropriately select how much tissue advancement or rotation can be accomplished without producing anatomic distortion of the surrounding structures. As with traditional rotation flaps, the movement of O–Z flaps produces paired dog-ear redundancies near the flaps’ pivot points, and these redundancies should be excised for the production of proper flap contour. Of course, this adds even further complexity to the O–Z flap’s potentially distracting incision lines. The O–Z repair has its greatest application on the scalp,7 where the flap’s prominent incision lines are typically hidden beneath a blanket of hair.

SELECTED ROTATION FLAPS

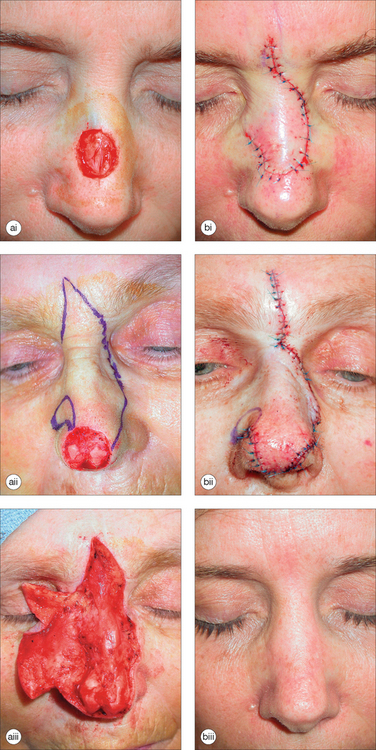

Dorsal Nasal Rotation Flap

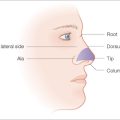

In 1967 Rieger introduced the dorsal nasal rotation flap for the reconstruction of distal nasal wounds.8 His flap was designed to pivot around a random pattern vascular pedicle that extended from the medial canthus and nasofacial sulcus and incorporated perforators from the angular artery. The flap described by Rieger is a full-thickness rotation of the entire nasal dorsum with a glabellar back cut to improve flap mobility. The flap is designed with a long sweeping arc that extends from the superior aspect of the defect to the nasofacial sulcus, past the contralateral medial canthus to a midpoint just superior to the glabella. In order to include the abundantly perfused underlying nasal musculature, the flap is elevated at the level of the underlying perichondrium or periosteum. Although not originally described by Rieger, it is often beneficial to change undermining planes at the glabella and elevate the flap above the procerus and medial inferior corrugators in this area. This avoids the transfer of thick glabellar skin to the thin skin of the contralateral medial canthus. The point of pivotal restraint with the dorsal nasal flap is located in the areas of the ipsilateral medial canthal tendon and the attachment of the nasal musculature to the nasofacial sulcus. As with all rotation flaps, undermining in the area of pivotal restraint can improve flap mobility, but this undermining should be performed under direct visualization in order to protect the flap’s vascular pedicle. Properly performed, the dorsal nasal flap can be used to repair distal nasal defects up to 2 cm in diameter and is most useful for medium-sized distal nasal defects too large to be repaired with bilobed transposition flaps and too small to warrant the use of two-staged pedicled flaps.

The dorsal nasal flap, the variations of which have been eloquently reviewed by Dzubow,9 has several advantages. Local nasal skin is used to repair a nasal wound, and in general a good texture and color match along with a minimally visible scar are achieved. The scars of the dorsal nasal flap are usually hidden in the cosmetic junctions of the alar crease and the nasofacial sulcus and within the glabellar frown lines. In addition, the dorsal nasal flap is among the heartiest nasal repairs and rarely suffers from vascular compromise. The main disadvantages of the dorsal nasal flap are its size and its generous undermining requirements. If pivotal restraint is inadequately freed, rotation is limited, and closing the wound may place undesirable tension on the free margin of the nose. If the defect is on the central nasal tip, insufficient flap rotation will cause the tip to elevate. Whereas in older patients this elevation, if symmetric, may not be a concern and may actually be beneficial because of correction of age-related nasal tip ptosis,10 in younger patients tip elevation produces a “pig nose” deformity. Flaps used to repair wounds located more laterally may produce to alar elevation and asymmetry. In general, by lengthening the flap and extending the leading edge beyond the defect, the surgeon can achieve sufficient flap rotation to prevent free margin elevation. Not all noses are alike. Elongate noses with relatively thin, nonsebaceous skin are readily repaired with the dorsal nasal flap, whereas shorter noses and those with thicker sebaceous tissue prove more challenging. Although longer incision lines may create aesthetic concerns in the early postoperative period, a longer arc of flap rotation will reduce the likelihood of the alar tip distortion that can result from a smaller flap.

Variants of the Dorsal Nasal Flap

Axial dorsal nasal rotation flap

Marchac based his dorsal nasal flap variant on an axial pedicle of vessels that emerge near the medial canthus.11,12 Based on reliable perforators emanating from the angular artery, the pedicle could be safely narrowed, allowing for removal of a long triangular dog-ear along the ipsilateral nasal sidewall. Removal of this standing cone allowed for optimal rotation and also diminished the fullness of the ipsilateral sidewall that resulted from rotation of the flap into the operative wound. The Marchac variation certainly allows for a greater degree of flap rotation but does so by creating even more incisions than the original Rieger flap (Figure 5.6).

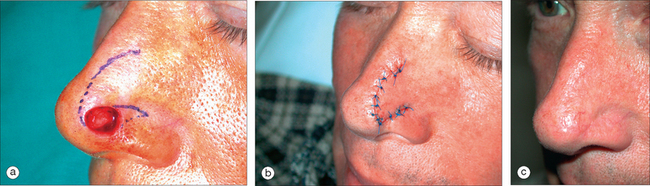

Heminasal rotation flap

In 1973, Rigg modified the dorsal nasal flap by designing a repair that utilized only a portion of the skin of the dorsal nose13 (Figure 5.7). The incision of the heminasal flap he described places the free edge of the flap directly on the midline dorsum of the nose to the glabella, and then back cuts to the ipsilateral inner canthus. This repair is most useful for relatively small lateral nasal wounds, where it provides a suitable alternative to the bilobed transposition flap. Similarly, defects of the lateral inferior nasal sidewall can sometimes be readily repaired with a mirror image heminasal rotation flap where the free margin of the flap rotates along the nasofacial sulcus. This repair requires that the flap rotate freely enough to avoid elevation of the ipsilateral nasal ala.

Other variants

For eccentric, off-center defects it is usually easier to create a nasal rotation flap with the pedicle based on the opposite side of the nasal bridge. Lateral defects are often best repaired with a heminasal rotation flap with the pedicle based on the same size of the defect. In many cases, a flap that utilizes only the nasal skin and avoids the glabella will suffice to close even a substantial distal operative wound.14 The dorsal nasal flap can be suitably modified for smaller defects. With such smaller flaps, it is not always necessary to extend the back cut superiorly onto the glabella or to extend the flap’s curvilinear excision far laterally onto the contralateral nasal sidewall. Small lateral and inferior wounds that are repairable with bilobed flaps may also be suitably repaired with small rotation flaps carefully elevated above the nasalis musculature (Figure 5.8). Such “distal nasal” rotation flaps are more sparsely reported in the medical literature, but they are useful in select cases.

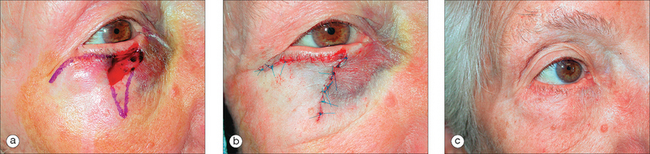

Tenzel and Mustarde Rotation Flaps

In 1966 Mustarde described a cheek rotation flap for lower eyelid reconstruction.15 In 1975 Tenzel and Stewart described a similar rotation flap from the temple for repair of full-thickness lower eyelid defects.16 The classic Mustarde flap is a large rotation of cheek and temple skin with necessary extension of the flap’s incisions into the distant preauricular cheek. The Tenzel semicircular flap is a similarly designed rotation of a skin and orbicularis muscular flap from the temple and lateral canthal areas. The classic Tenzel flap also incorporates a cantholysis of one crus of the lateral canthal tendon in order to facilitate flap rotation. Originally described by the author as an advancement flap, the Tenzel flap actually constitutes a combination of advancement and rotation about a pivot point on the zygoma. A superiorly arcing semicircular incision lateral to the canthus allows for the recruitment of adjacent tissue for reconstruction of the lower lid. Both the Mustarde and Tenzel flaps utilize the primary motion of the flap to support the eyelid, and both flaps direct all wound closure tensions towards the temple superolaterally and toward the cheek medially. Because the flaps disperse tensions in these directions, unwanted vertically directed tension along the eyelid margin is avoided, and the appropriate position of the lower lid can be maintained. Similar to the design of the rotating dorsal nasal flap, the Mustarde and Tenzel flaps’ long arcs of rotation allow the redistribution of the volume of the primary defect along a narrowed secondary defect. Because the secondary defect with both of these flaps is located within the compliant and mobile skin of the temple and cheek, distortion of the surrounding structures is minimized.

These useful rotation flap reconstructions have been commonly modified,17,18 and they are reliable flaps for the repair of defects of the lower eyelid and defects that span the lower lid and adjacent cheek or zygoma. The most commonly employed flap variant is a modified Tenzel flap used to repair partial-thickness defects of the mid-to lateral lower eyelid (Figure 5.9). From the superior extent of the surgical defect, a curvilinear rotation is extended laterally and superiorly past the lateral canthus and onto the temple. As with the traditional rotation flaps mentioned earlier, the superior extension of the flap’s design allows the flap’s rotation to overcome the “shortening” associated with pivotal restraint. If the arc of rotation is not extended superiorly, the eyelid will be required to undergo secondary motion to meet the leading edge of the flap, and an iatrogenic ectropion can be produced. The flap is elevated just above the orbicularis oculi superomedially, above the medial insertions of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) inferiorly, and over the superficial temporal fascia superolaterally. All tension is directed horizontally along the vector of the primary motion. As the wound is closed, the temporal arc of the rotation/advancement supports the lower lid and prevents ectropion. This is one type of rotation flap where the maximum tension vector remains entirely in the direction of the primary motion. By having an oversized arc of rotation, the flap places essentially no tension on the medial portion of the secondary defect, thus avoiding tension on the lower lid margin. Because temple skin is inherently thicker than eyelid skin, it is important to adequately thin the superior aspect of the flap to avoid placing a thick flap adjacent to the remaining thin tissue on the lower eyelid. The modified Tenzel flap often produces temporary edema of the lower lid due to the obstruction of the laterally draining lymphatic channels, but this edema is rarely persistent for more than several weeks. As noted earlier, the modified Tenzel flap is also useful for sizeable defects that involve not only the lid but also the area just below the infraorbital crease over the zygoma or more medial cheek (Figure 5.10).

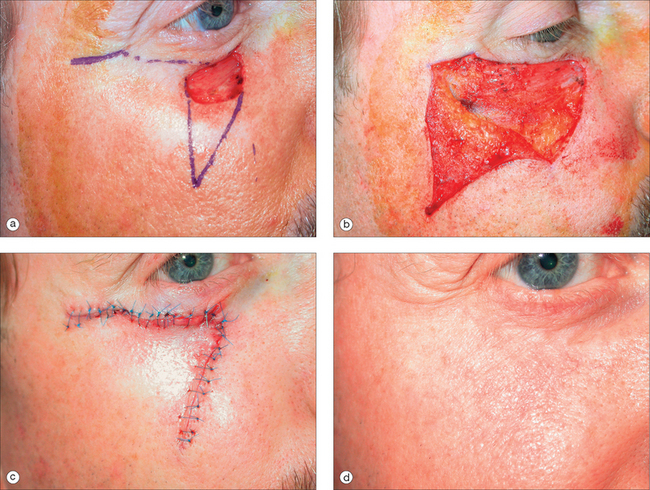

Medial Cheek Rotation Flap

Defects of the medial cheek near the junction of the lower lid and nasal sidewall can often be repaired linearly or with local tissue advancement. It is common, however, to be presented with a postoperative wound that is inferior and lateral to the medial canthus, oval in shape, and oriented along the lower lid crease. Such elongate wounds are often due to the tendency of basal cell carcinomas in this region to extend along the infra-orbital crease as a path of lower resistance. Similarly, sizeable defects including portions of lateral nose, medial cheek, and inferomedial lower lid are common. Advancement in this location can be difficult because of the relatively minimal horizontal laxity of the medial cheek. Linear repair places tension on the medial lower lid margin and can produce either a “pulled lid” appearance or a medial ectropion. For these reasons, very large defects in this area can be repaired with a large sweeping rotation/advancement flaps that extend to the temple, but for smaller wounds, elegant and smaller medial cheek rotation flaps are often suitable. In such repairs, curvilinear dog-ear incisions are designed along the lower lid crease to triangulate the primary defect. The arc of this rotation flap extends down along the nasofacial sulcus and nasolabial fold, where a dog-ear excision at the inferior extent may be required. The flap is elevated just above the orbicularis oculi superiorly, at the level of the nasalis medially, and just above the levator labii superioris inferiorly. When this flap is elevated just above the facial musculature and within the loose fat of the medial cheek, it is usually a very easy flap elevation with minimal bleeding. Once the deep and lateral restraints have been freed, the flap will rotate superomedially under minimal tension. In order to support the lower lid and prevent ectropion, the dermis of the center of the tip of the flap is tacked carefully to the periosteum of the nasal bone or medial maxilla (Figure 5.11). This single stitch, which can be a 4-0 Vicryl suture, supports the weight of the flap and closes the primary defect along the lid crease. The nasofacial sulcus is then repaired with a bilayered closure. Only one or two deep sutures are usually required along the cheek–lid junction.

Cervicofacial Rotation Flaps

Cheek defects of up to 5 to 10 cm diameter may be repaired with long sweeping cervicofacial rotation flaps. The cervicofacial rotation is drawn as an arc from the superior aspect of the operative wound superolaterally arcing past the zygoma, in front of the ear, and far down onto the neck. The flap is elevated within the loose, deep facial adipose superiorly and laterally and then just above the platysma inferiorly on the neck. The flap must be thoroughly undermined under the medial and inferior pedicle to free the flap’s rotation over the jaw. If the rotation is extended inferiorly to the clavicle, enormous facial operative wounds can be suitably repaired.19,20

Rotation Flaps on the Chin and Lip

Rotation flaps may be utilized to repair large chin defects. The arc or rotation is placed along the mental crease, and a triangular dog-ear is removed beneath the primary operative wound. Elevated just above the mentalis muscle and undermined over the mandible, chin rotation flaps will move a great distance and reliably close large wounds (Figure 5.12). Defects of the lateral portion of the upper lip adjacent to the ala are readily repaired with small rotation flaps in which the arc of the rotation starts at the alar crease and extends inferolaterally along the nasolabial fold. As the flap rotates into the primary defect, the nasolabial fold is pulled slightly medially, but this is not usually noticed by the casual observer. The small dog-ear that results from flap rotation into the primary defect is removed inferior to the primary operative defect. This flap works best in patients who have a substantial apical triangle of lip between the lateral alar crease and the nasolabial fold.

PLANE OF FLAP ELEVATION AND SURGICAL UNDERMINING

Rotation flaps must be liberated from attachments to the deeper subcutaneous tissues before they can properly move. Undermining is very effective at reducing wound closure tension, and a properly designed and undermined flap repair is ideally draped over the operative wound under minimal tension. Sharp undermining with a scalpel or Shea undermining scissors under direct visualization is preferred by many surgeons since the flap can be elevated within a uniform and predictable plane.21 When a fascial plane such as the SMAS or muscular plane is encountered, undermining can often be accomplished with great precision using electrosection.

Suspension (or tacking) sutures are sutures that anchor a portion of a flap repair to underlying immobile structures such as the periosteum. Suspension sutures are used to shift tension away from the edges of a flap, to reorient the tension vector of a flap, or to tack down a flap at a point of facial concavity where the flap would otherwise tent and create a potential dead space.22 Tacking is usually performed with a 4-0 Vicryl®, nylon, or polypropylene suture. A classic example of how a tacking suture may be utilized to redirect tension is a medial cheek rotation flap used to close an infraorbital wound. The dermis of the advancing edge/tip of the flap is tacked to the nasal sidewall at the superior and medial extent of the rotation. This single suture effectively closes the primary defect and takes all tension off of the leading edge of the flap, thus preventing ectropion formation. Similarly, tacking sutures are often used to tack large cheek and temple rotation flaps to the zygoma or to the lateral orbital rim or temple.

1 Dzubow LM. Rotation flaps. In: Dzubow LM, editor. Facial flaps. Biomechanics and regional application. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange; 1990:31-41.

2 Ahuja RB. Geometric considerations in the design of rotation flaps in the scalp and forehead region. Plast Reconst Surg. 1988;8:900-906.

3 Dzubow LM. The dynamics of flap movement: Effect of pivotal restraint on flap rotation and transposition. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1348-1353.

4 Kroll S, Margolis R. Scalp flap rotation with primary donor site closure. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;30:452-455.

5 Larrabee WF, Sutton D. The biomechanics of advancement and rotation flaps. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:726-734.

6 McGregor IA. Local skin flaps in facial reconstruction. Otolaryngol Clin NA. 1982;15:77-98.

7 Albom MJ. Repair of large scalp defects by bilateral rotation flaps. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1978;4:906-907.

8 Rieger RA. A local flap for repair of the nasal tip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40:147-149.

9 Dzubow LM. Dorsal nasal flaps. In: Baker SR, Swanson NA, editors. Local flaps in facial reconstruction. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995:225-246.

10 Preaux J. Le lambeau nasal de Rieger. Histoire, raffinements techniques et indications. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2000;45:9-16.

11 Marchac D. Lambeau de rotation frontonasal. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1970;15:44-49.

12 Marchac D, Toth B. The axial frontonasal flap revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:686-694.

13 Rigg BM. The dorsal nasal flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;52:361-364.

14 Greeen RK, Angeles J. A full skin rotation flap for closure of soft tissue defects in the lower one-third of the nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:163-166.

15 Mustarde JC. The use of flaps in the orbital region. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;45:146-150.

16 Tenzel RR, Stewart WB. Eyelid reconstruction by the semicircle flap technique. Ophthalmol. 1978;85:1164-1169.

17 Rao GP, Frank HJ. Surgical management of lower-lid basal cell carcinoma involving the medial canthus: A modification of the Mustarde cheek rotation flap. Ophthalm Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14:367-369.

18 McGregor IA. Eyelid reconstruction following subtotal resection of upper or lower lid. Br J Plast Surg. 1973;26:346-354.

19 Shestak KC, Roth AG, Jones NF, et al. The cervicopectoral rotation flap—a valuable technique for facial reconstruction. Brit J Plast Surg. 1993;46:375-377.

20 Katz AE, Grande DJ. Cheek-neck advancement-rotation flaps following Mohs excision of skin malignancies. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:949-955.

21 Boyer JD, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Undermining in cutaneous surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:75-78.

22 Salache SJ, Jarchow R, Feldman BD, et al. The suspension suture. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:973-978.