33 Role of Minimally Invasive Cervical Spine Surgery in the Aging Spine

KEY POINTS

Introduction

The aging of the population in industrialized nations appears to be an inevitable situation. It does not simply mean an increase in life expectancy owing to the improvement of medical science and health care, but additionally a significant decrease in birth rates has led to this situation. Back and neck pain are most frequently occurred presentations of older people, and the unique nature of the spine makes those problems highly complex to evaluate and to manage. The spine is a very specific anatomic and functional unit. The findings of radiological degenerative changes of the cervical spine in aging population are common. By the fourth decade of life, 30% of asymptomatic subjects show degenerative changes of the intervertebral discs, whereas by the seventh decade, up to 90% have developed degenerative alterations.1,2 Thus, it is always important to interpret such radiological features in the light of the clinical presentation. If symptoms and findings are not correlated, the presence of a different pathology should be suspected, and appropriate evaluations are required. In order to assess the spine unit of patients (clinical, radiological; and laboratory findings; neurophysiology, etc.), cooperation between the orthopedic surgeon, the neurosurgeon, and the neurologisted is needed. Based on the present illness and physical examinations, a proper neurological workup should be performed. In addition to the neurological assessment, additional laboratory evaluations and other studies may be helpful in the differential diagnosis, including electromyography (EMG), electroneurography (ENG), sensory evoked potentials (SEP), and motor evoked potentials (MEP).

The aging of the spine induces considerable alterations in anatomical structures: discs, facet joints, ligaments, muscles, and bones. The degeneration of some of these structures can be responsible for the injury to the neural structures by herniated disc, spinal stenosis, and other degenerative disease.1

Basic Science

As a flexible, multisegmental column, the functional role of the spine is to provide stabilization and upright position. The spine is composed of a static, changeless component, the vertebral bodies, and an elastic mobile component, the three joint complexes, consisting of the intervertebral disc and the two posterior facet joints. As mentioned earlier, the aging spine experiences considerable changes in anatomy (the structural components, biomechanics, etc.).2

The quantity of water present in the nucleus pulposus (contains a high proportion of hydrophilic glycosaminoglycans) decreases and both spinal height and the cushioning effect are reduced with aging. Gaps and fissures may develop in the discs, and with the time they may become desiccated and even ossified. As the disc height decreases, there may be a buckling of both anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments. The buckling posterior ligaments may project into the spinal canal, reducing the space available for the spinal cord. Bony osteophytes may develop in the region of the vertebral bodies; endplate osteophytes may expand across the disc spaces and merge with osteophytes of adjacent vertebrae to form bridging osteophytes. If the osteophytes involve posterior endplates, they may protrude into the spinal canal, compressing the dural sac. People with congenitally narrowed spinal canals have greater risk for spinal cord compression as a result of these changes. Large bridging osteophytes on the anterior endplates may lead to severe problems in gastrointestinal, respiratory, or vascular systems. The size of the neural foramen, which the spinal nerves pass through, may be decreased both with the loss of spinal length and ossification and hypertrophy of these soft tissues around the vertebral column. Such age-related changes demonstrate the symptomatology in most patients presenting for cervical spine surgery.1,2

Radiological Evaluation

Routine cervical spine radiographs, including anteroposterior, lateral, flexion, extension, and both oblique views, are taken for the evaluation of degenerative disc disease. The narrowing of the intervertebral disc space and neural foramen, formation of osteophytes or bony spurs, subluxation of facet joints, and segmental instability are commonly shown in degenerative cervical diseases. Although cervical radiographs and CT scanning are useful for visualizing bony anatomy and overall alignment of the spine, they are limited in the evaluation of neural structures, such as neural foramen, spinal cord or nerve roots, and the presence or absence of neural compression.

Surgical Techniques

Anterior Cervical Microforaminotomy

Lower Vertebral Transcorporeal Approach

The transverse skin incision about 1 to 2 inches then the platysma can be split longitudinally or dissected transversely. Blunt dissection proceeds medially to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and internal carotid artery toward the anterior aspect of the cervical vertebrae.

Case Studies

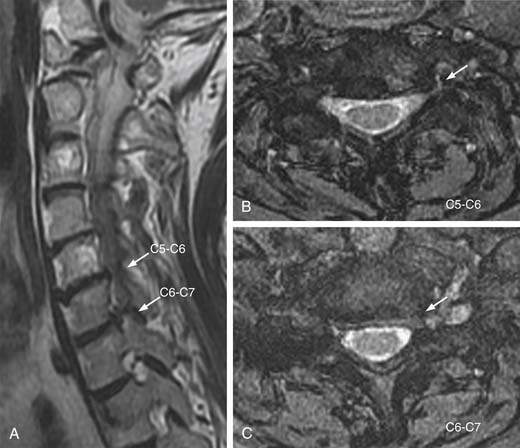

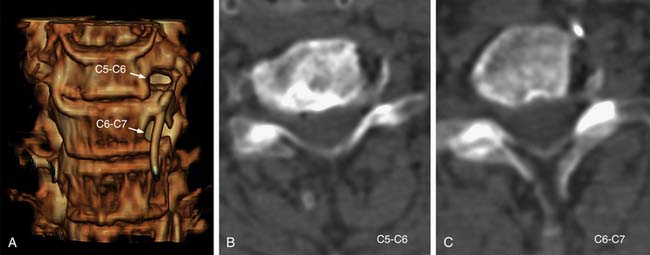

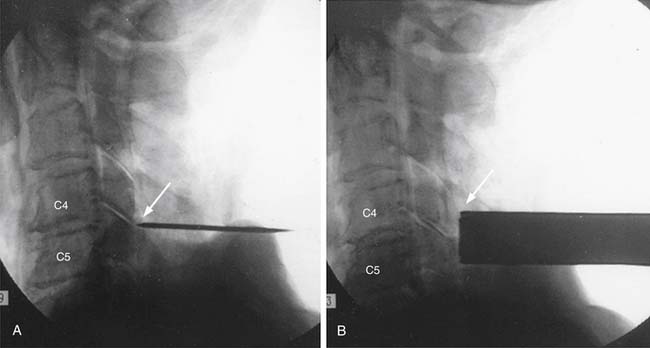

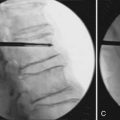

A 67-year-old woman had continuous radiating pain into her left arm. During 6 months of conservative treatment and physiotherapy, the symptoms were not relieved. Plain radiographs showed decrease in the height of disc space at the level of C5-C6 (Figure 33-1 ). Cervical MRI demonstrated narrowing and obstruction of neural foramen at the levels of C5-C6 and C6-C7 (Figure 33-2 ). The decision was made to perform a microsurgical decompression with anterior foraminotomy at both cervical segments. Transuncal approach at C5-C6 and upper vertebral transcorporeal approach at C6-C7 were performed, respectively. Plain and dynamic radiographs and three-dimensional (3-D) cervical CT were done postoperatively (Figure 33-3). The radiculopathy was significantly improved after the operation. The patient was symptom free, and 3-D CT and dynamic radiographs showed no instability of operated levels at follow-up.

Percutaneous Cervical Nucleoplasty

Percutaneous disc decompression, regardless of technique, has been based on the concept that a small reduction of volume in a closed hydraulic space results in a disproportionately large drop of pressure in the intervertebral disc space. Percutaneous cervical discectomy (PCD) has been developed as an effective treatment method for soft cervical disc herniation. Percutaneous cervical nucleoplasty (PCN) is one of the new minimally invasive techniques that uses radiofrequency energy to ablate the nucleus pulposus (Figure 33-4).

Microendoscopic Discectomy

Microendoscopic discectomy (MED) (Figure 33-5) is used when there is a need to visualize across the spinal canal and an operating microscope is insufficient. Positioning and anesthesia are the same as those for a posterior cervical microendoscopic foraminotomy. Single level and multilevel decompression can be performed with the standard fixed-aperture tubular retractor. For two-level decompression, the tube can be angled rostrally or caudally. The incision should be centered on a point between the two interspaces. For a three-level grated decompression, a longer incision can be used. A longer incision allows better visualization and decreases the amount of soft tissue resection required. For multilevel decompression, an expandable working channel can be used. Generally, it is easiest to begin with the most caudal level first, minimizing the amount of blood running into the field. After the level has been confirmed with fluoroscopy, soft tissues are cleared off the level of interest and the lateral edges of the lamina are defined. To minimize the risk of injury to the spinal cord, a high-speed drill is used to remove the lateral aspect of the lamina. If an ipsilateral foraminotomy is not needed, take care not to injure the facet capsule. Otherwise, the high-speed burr and Kerrison punches can be used to perform foraminotomy. The tube is then angled medially, exposing the base of the spinous process. The high-speed burr is used to drill away the base of the spinous process. It is usually necessary to angle the working channel rostrally to resect the remainder of the spinous process. Fluoroscopy can be used to confirm the rostrocaudal extent of the decompression. The ligamentum flavum is initially left intact to protect the underlying dura mater. But, to get adequate visualization of the contralateral aspect of the spinal canal, the ligamentum flavum is resected with the aid of curettes and Kerrison punches. The undersurface of the contralateral lamina should be drilled away to provide better visualization. Decompression is complete when a nerve hook can be passed along the lateral aspect of the dura mater contralaterally. Once a single level has been decompressed, further levels can be decompressed with a high-speed burr or a Kerrison punch. Bone bleeding should be waxed as soon as possible to reduce the risk of venous air embolism. The operative wound is then repaired in layers like other cervical spine procedures.

Discussion

In recent years the general trend in spinal surgery has been one of reductionism and minimization. The concept of minimally invasive cervical spine surgery is ideal for the management of cervical aging disease. The extensive muscle dissection required for the traditional posterior approaches leads to significant postoperative pain and the potential for postoperative deformity. By minimizing the extent of muscular dissection and by preserving the contralateral soft tissue, the less invasive approaches may lead to shortened hospital stays, decreased narcotic use, and better outcomes.

Stookey3 described the clinical symptoms and anatomic location of cervical disc herniation in 1928. Subsequently, the landmark paper by Mixter and Barr4 clearly established the relationship between herniated discs and sciatica, and provided evidence that laminectomy and disc excision could successfully relieve pain associated with radiculopathy. Bailey and Badgley5, Cloward6, and Robinson and Smith7 popularized the anterior approach with interbody fusion in the 1950s. Hirsch8 and Robertson9 recommended cervical discectomy without fusion. Fukushima10 introduced the ventriculofiberscope in 1973 and further enhanced the foundation for percutaneous endoscopic cervical discectomy.3,4

Microsurgical Anterior Cervical Foraminodiscectomy

In the 1930s, Spurling and Scoville11, and Frykholm12 pioneered the posterior cervical approach for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. But the posterior approach was limited in dealing with central compressive pathology and the open approach was associated with significant muscle morbidity. Subsequently, in the 1950s, the anterior approach was described and popularized. Compared to the open posterior approach, the anterior approach is generally associated with shorter recovery times but has a greater potential for complication. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) results in a loss of mobility at the operated level, and increases rates of degenerative disc disease in adjacent levels. In addition, the compressive pathological factors are located anteriorly, and the immediate surgical outcomes of anterior discectomy are fairly good. However, the consequences of anterior disc-ectomy are obvious. Conventional anterior discectomy and fusion requires complete removal of the remaining disc in the intervertebral disc space, which results in loss of the functional motion unit.13

Percutaneous Cervical Nucleoplasty(PCN)

Treatment of cervical disc hernia with PCN is safe to perform, and the efficacy of this technique is good in patients. The advantage of PCN is that it reduces the volume and pressure of the affected disc without damaging other spinal functional units. Ablation of a relatively small volume of the nucleus pulposus results in a significant reduction in intradisc pressure. Histologic examination revealed no evidence of direct mechanical or thermal damage to the surrounding tissues in human cadavers. Given these radical thermal penetrations, high temperatures and lethal thermal doses do not occur in small regions outside of the nucleus or within the bone endplates in human cadavers.14

A small number of complications are associated with PCN. With the approach from the anterior neck to disc space, it is important to monitor the distance from the tip of the needle to the spinal canal. Therefore monitoring of the needle is essential during this procedure. X-ray fluoroscopy is used to confirm the correct position of the needle tip during placement of the needle, permitting accurate nucleoplasty of the intervertebral disc. Vascular injury can occur if the device contacts an artery or a vein. Particular care should be taken to avoid puncture of the anterior annulus. But, according to Chen’s study15 in human cadavers, intradiscal pressure was markedly reduced in the younger, healthy disc cadaver. In the older, degenerative disc cadavers, the change in intradiscal pressure after nucleoplasty was very small. There was an inverse correlation between the degree of disc degeneration and the change in intradiscal pressure. Their conclusion is that pressure reduction through nucleoplasty is highly dependent on the degree of spine degeneration. Nucleoplasty markedly reduced intradiscal pressure in nondegenerative discs, but had a negligible effect on highly degenerative discs.

Percutaneous Endoscopic Cervical Discectomy

Since the first description of cervical percutaneous discectomy by Tajima and colleagues16 in 1981, percutaneous endoscopic cervical discectomy (PED) may be considered a good alternative to the standard anterior cervical discectomy and fusion for treating soft cervical disc herniation. The goal of this procedure is to decompress the spinal nerve root through percutaneously removing the herniated mass and shrinking the nucleus pulposus while the patient is under local anesthesia.

Minimally invasive PED under local anesthesia can prevent such complications as epidural bleeding, perineural fibrosis, graft-related problems, dysphasia, hoarseness, and so on. It also maintains the stability of the intervertebral mobile segment and provides patients with excellent cosmetic effect and early recovery. Moreover, it does not preclude further open procedures even after treatment failure. But PED is contraindicated in patients presenting with a severe neurologic deficit, segmental instability, acute py-ramidal syndrome, progressive myelopathy, and other pathologic conditions, such as tumor, fracture, infection, and nerve entrapment with scar tissue from previous surgery. This procedure is also contraindicated in patients who have migrated discs, calcified disc protrusion, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, marked spondylosis with disc space narrowing, and neurologic or vascular pathologies mimicking disc herniations.17

Microendoscopic Discectomy

Frykholm and Scoville described posterior foraminotomy through partial resection of the medial part of the facet joint to relieve the compression of the cervical nerve root in radiculopathy patients. Conventional posterior approaches have the disadvantage of detaching the extensor cervical muscles from the laminae and the spinous process. This operative trauma to the cervical paraspinal muscles is a major cause of postoperative complications in the form of persistent neck and shoulder pain, and sometimes spinal instability may result.18

Roh et al19 described the use of microendoscopic posterior cervical foraminotomy in a cadaveric study, and Burke and Caputy20 reported on the use of the same technique. The microendoscopic technique has the advantage of providing a minimally invasive approach through transmuscular dilatation. However, the disadvantage of this procedure is that it only allows two-dimensional visualization, and the view often gets blocked by bleeding or obscured by fragments during removal. The main limitation of this procedure is in the treatment of severe bony stenosis that necessitates laminectomy to decompress the spinal cord.

1. Szpalski M., Gunzburg R., Mélot C.M., et al. The aging of the population: a growing concern for spine care in the twenty-first century. Eur. Spine J.. 2003;12(Suppl. 2):S81-83.

2. Benoist M. Natural history of the aging spine. Eur. Spine J.. 2003;12(Suppl. 2):S86-S89.

3. Stookey B. Compression of the spinal cord due to ventral extradural cervical chondromas. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry. 1928;20:275-278.

4. Mixter W.J., Barr J.S. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1934;211:210-215.

5. Bailey R.W., Badgley C.E. Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. J. Bone. Joint. Surg. Am.. 1967;42-A:565-594.

6. Cloward R.B. The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks. J. Neurosurg.. 1958;15(6):602-617.

7. Smith G.W., Robinson R.A. The treatment of certain cervical-spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J. Bone. Joint. Surg .Am.. 1958;40-A(3):607-624.

8. Hirsch C., Wickbom I., Lidstroem A., Rosengren K. Cervical-disc resection: A follow-up of myelographic and surgical procedure. J. Bone. Joint. Surg. Am.. 1964;46:1811-1821.

9. Robertson J.T., Johnson S.D. Anterior cervical discectomy without fusion: Long-term results. Clin. Neurosurg.. 1980;27:440-449.

10. Fukushima T., Ishijima B., Hirakawa K., Nakamura N., et al. Ventriculofiberscope: a new technique for endoscopic diagnosis and operation. Technical note, J. Neurogurg.. 1973;38(2):251-256.

11. Spurling R.G., Scoville W.B. Lateral rupture of the cervical intervertebral discs. A common cause of shoulder and arm pain. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet.. 1944;78:350-358.

12. Frykholm R. Deformities of dural pouches and strictures of dural sheaths in the cervical region producing nerve root compression. J. Neurosurg.. 1947;4:403-413.

13. Jho H.D. Spinal cord decompression via microsurgical anterior foraminotomy for spondylotic cervical myelotomy. Minim. Invasive Neurosurg.. 1997;40:124-129.

14. Onik G.M., Kambin P., Chang M.K. Minimally invasive disc surgery. Nucleotomy versus fragmentectomy. Spine. 1997;22:827-828.

15. Chen Y.C., Lee S.H., Chen D. Intradiscal pressure study of percutaneous disc decompression with nucleoplasty in human cadavers. Spine. 2003;28(7):661-665.

16. Tajima T., Sakamoto H., Yamakawa H. Discectomy cervicale percutanee. Rev. Med. Orthoped.. 1989;17:7-10.

17. Ahn Y., Lee S.H., Chung S.E., et al. Percutaneous endoscopic cervical discectomy for discogenic cervical headache due to soft disc herniation. Neuroradiology. 2005;47(12):924-930.

18. Krupp W., Muke R. Clinical results of the foraminotomy as described by Frykholm for the treatment of lateral cervical disc herniation. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 1990;107:22-29.

19. Roh S.W., Kim D.H., Cardoso A.C., Fessler R.G. Endoscopic foraminotomy using MED system in cadaveric specimens. Spine. 2000;25(2):260-264.

20. Burke T.G., Caputy A. Microendoscopic posterior cervical foraminotomy: a cadaveric model and clinical application for cervical radiculopathy. J. Neurosurg.. 2000;93 (Suppl. 1):126-129.