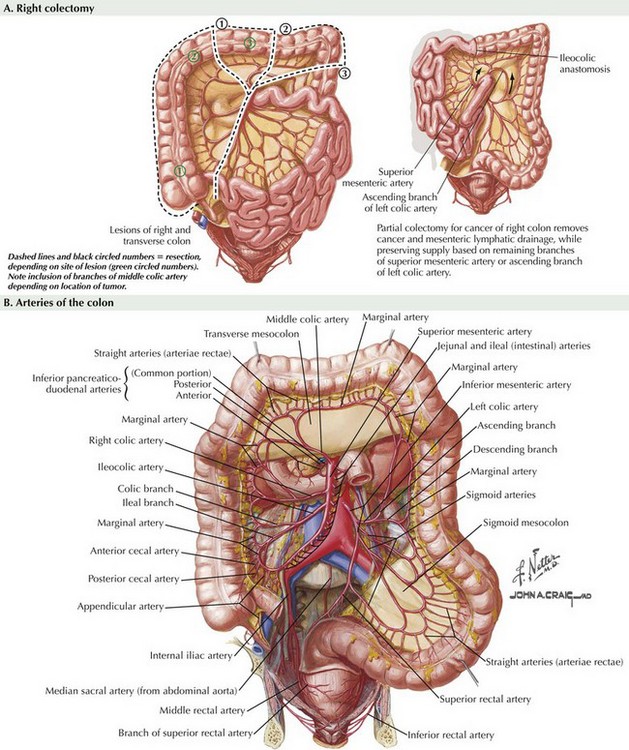

Right Colectomy

Superficial Anatomy and Topographic Landmarks

Before making an incision, either laparoscopic or open, it is important to understand the relationship between surface anatomy and the abdominal anatomy (Fig. 21-1, A). Understanding the location of the most difficult part of the anatomy or most tethered portion of the colon will assist in appropriately placing an incision. Also, in the morbidly obese patient, surface anatomy, such as the location of the umbilicus, may be greatly altered. The umbilicus may reach down to the pubis and overlie a large pannus, which may distort normal relationships with internal anatomy.

Although the right colon is typically tethered by the ileocolic artery, lateral attachments, and the middle colic artery, the inferior portion of the right colon and ileum will be very mobile after the surgery is performed. Attachments to the middle colic and lesser sac are typically the most tethered portion of the operation. In addition, appropriate isolation and evaluation of adequate blood flow of the middle colic vessels is often the most difficult part of the case (Fig. 21-1, B). For this reason, laparoscopic extraction incisions are usually made over the middle colic arteries.

Anatomic Approach to Right Colectomy

Identification of Ileocolic Vessels

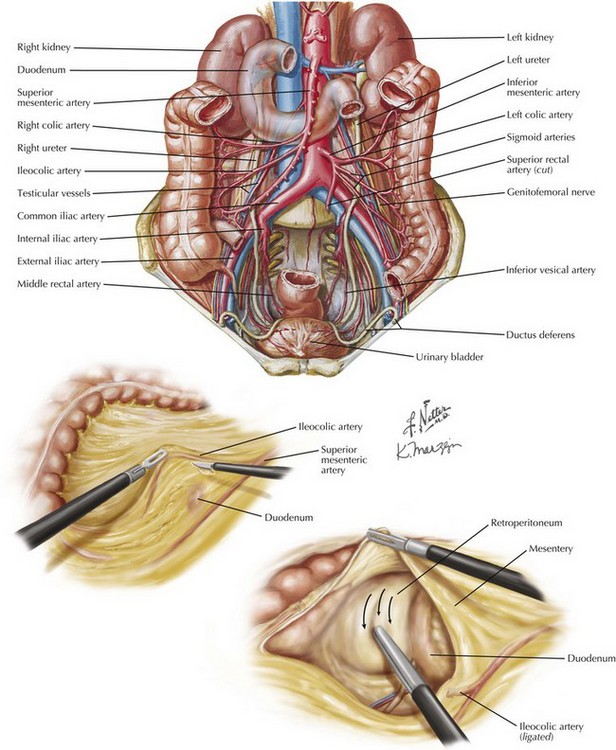

Once the avascular plane is identified, dissection can be carried posterior to the mesentery in a superior, medial, and lateral direction within this avascular space. Borders of the space will be the mesentery of the right colon superiorly, attachments of the colon to the liver superiorly and Toldt’s fascia laterally. The retroperitoneum will form the floor of the space (Fig. 21-2).

Just lateral to the origin of the ileocolic vessels, care must be taken to prevent injury to the duodenum, which lies close to the SMA-ICA junction. Just above the duodenum, a subtle change in fat identifies the head of the pancreas, which should also be preserved. In fact, the plane anterior to the head of the pancreas mobilizes the transverse colon mesentery to complete the medial dissection for a right colectomy. Reaching the liver superiorly, the pancreas medially, and Toldt’s fascia laterally facilitates later dissection (Fig. 21-2).

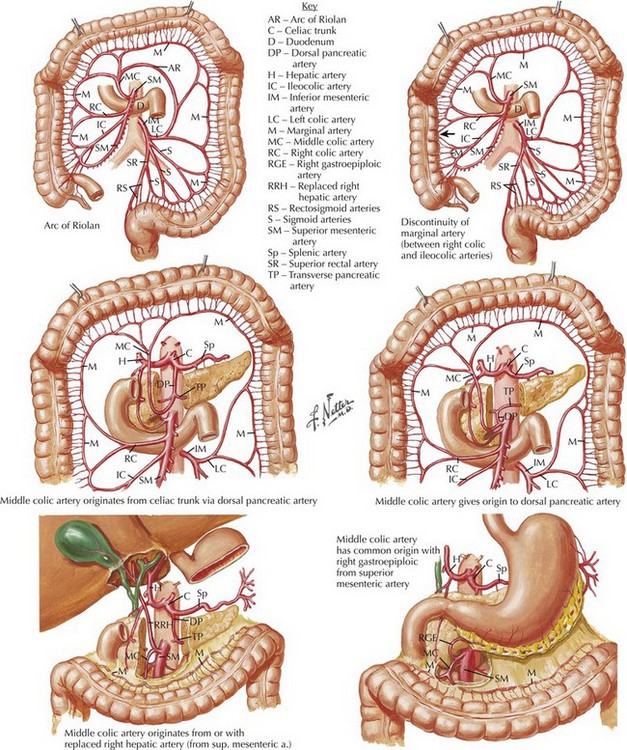

Variation in Arteries of Right Colon

Many textbooks demonstrate a distinct ICA and right and middle colic vessels, but arterial variation is common in this location. Often, the right colic artery (RCA) is either a branch from the ICA or not found at all. If a high ligation of the ICA is performed, the RCA may not need to be transected again. If it is a separate branch of the SMA, the RCA will also need to be transected, high if the operation is performed for oncologic reasons (Fig. 21-3).

Mancino, AT. Laparoscopic colectomy. In Scott-Conner CEH, ed.: The SAGES manual: fundamentals of laparoscopy, thoracoscopy and GI endoscopy, 2nd ed, New York: Springer, 2006.

Okuda, J, Tanigawa, N. Right colectomy. In: Milson JW, Bohm B, Nakajima K, eds. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery. New York: Springer, 2006.

Scott-Conner, CEH, Right colectomy for cancer. Chaissin’s operative strategy in general surgery: an expositive atlas, 3rd e. Springer: New York, 2002.

Sonoda, T. Laparoscopic medial to lateral. In: Wexner SD, Fleshman JW, eds. Colon and rectal surgery: abdominal operations. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2012.