RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Case vignette

A 44-year-old female presents with severe depression. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis 3 years ago. She has experienced painful upper- and lower-extremity small joint arthritis despite therapy with multiple agents. The disease has progressed despite therapy, leading to deformed fingers, and she has had to give up her job as a designer. Lately she has experienced extreme fatigue and progressive dyspnoea. In the wake of these symptoms she has gone through the break-up of her 10-year marriage.

On examination the patient appears cushingoid and has a flat facial affect. Upper limb examination shows mild ulnar deviation of her fingers bilaterally. Proximal interphalangeal joints and metacarpophalangeal joints are tender, warm and boggy to palpation. On auscultation of her lung fields there are fine crepitations distributed widely. Her JVP is elevated and she has peripheral oedema.

Approach to the patient

History

Ask about:

• joint pain, stiffness, swelling and tenderness

• distribution of the joint symptoms

• onset, duration and frequency of symptoms—age of onset is important

• pain on moving the neck—would suggest involvement of the cervical spine, particularly the upper segment

• whether the patient has experienced any neurological deficit in the way of localised weakness and/or sensory loss

• dyspnoea or exertional dyspnoea

• any extraarticular features (as listed in the box below)

• whether the patient suffers from any constitutional symptoms, such as lethargy/ fatigue, anorexia, weight loss or fever

• the impact of the disease on the patient’s social life, occupational life, finances and overall quality of life

• the various treatment modalities tried, and their effects and side effects

• toxicities the patient has experienced with NSAIDs and slow-acting anti-rheumatoid arthritis drugs (SAARD)—should be especially enquired into

• detailed history of the psychosocial impact of the disease.

Examination

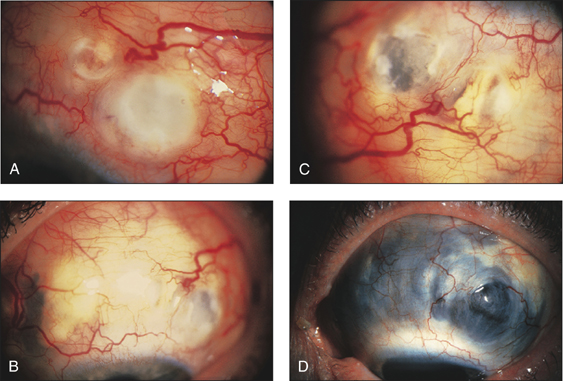

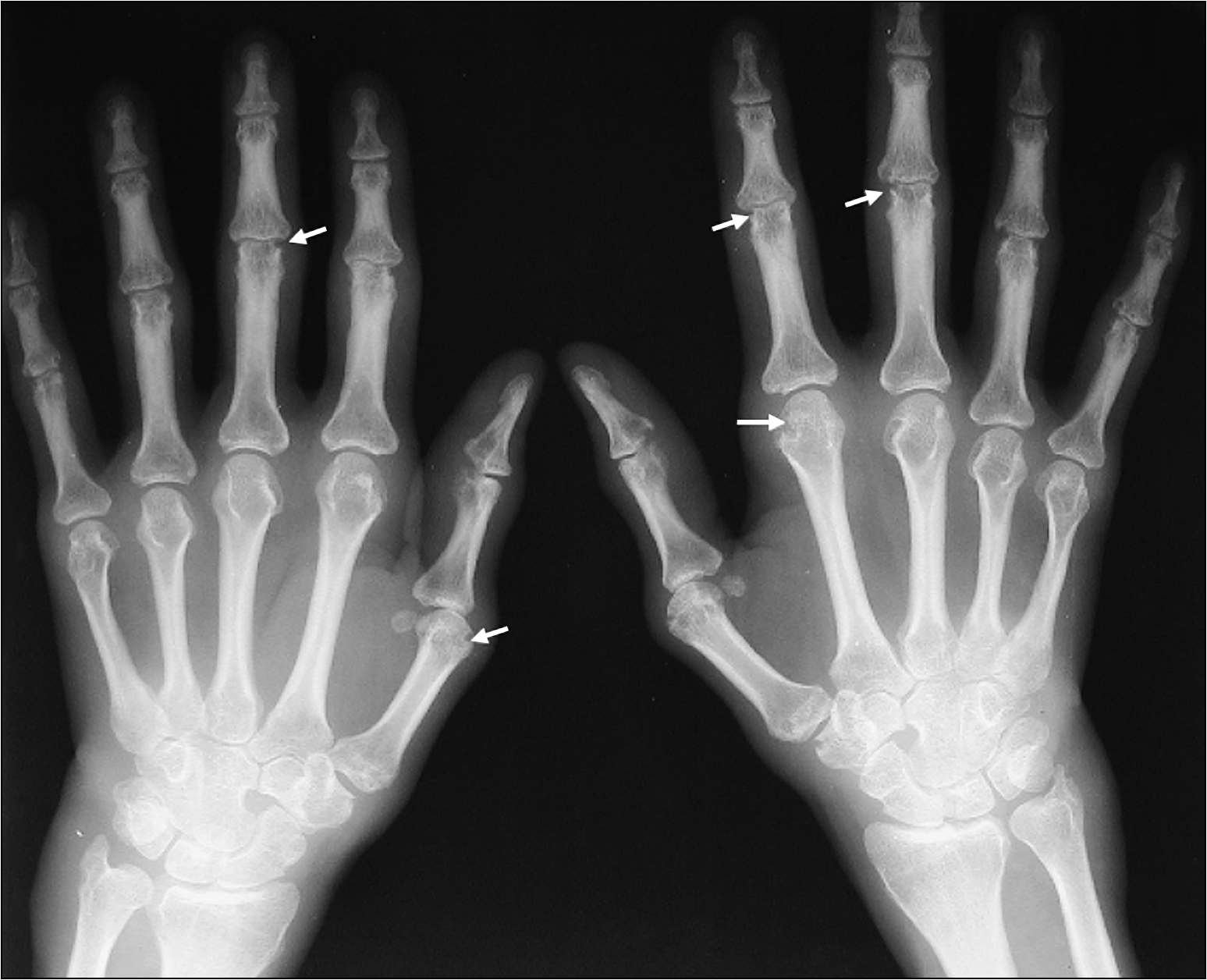

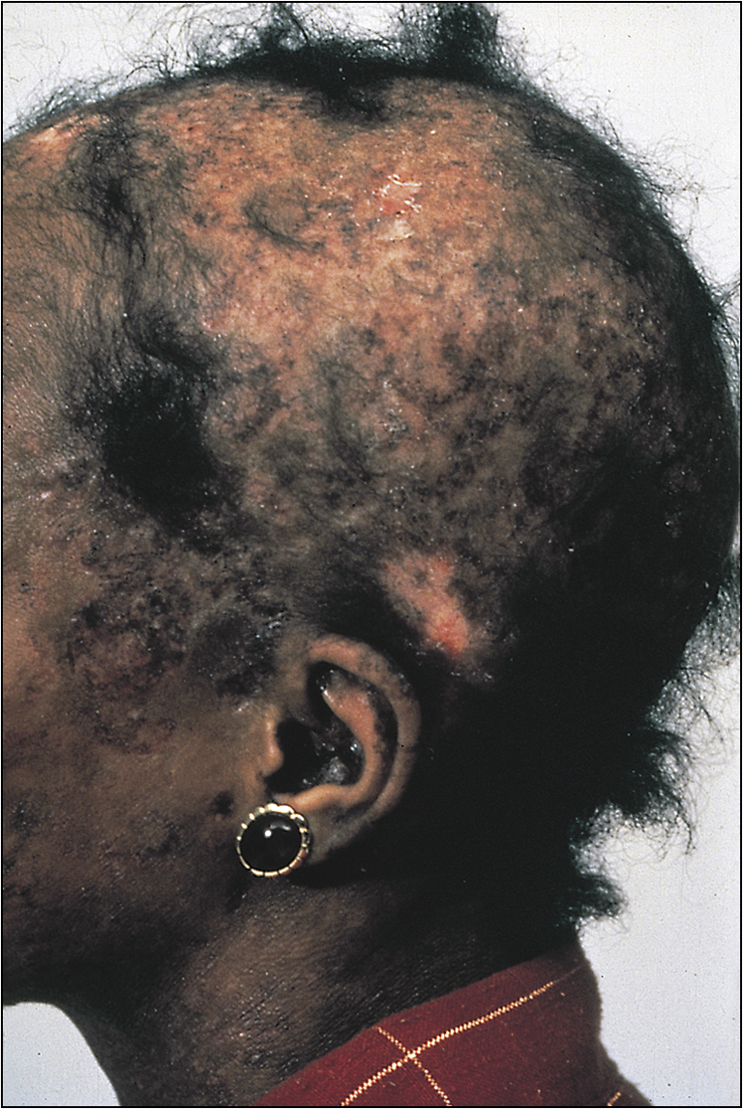

The examination needs to be detailed and meticulous. Look for wasting or cushingoid body habitus. Note any skin bruises, oral ulcers, oral candidiasis or surgical scars. Look for features that are characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis, such as symmetrical distribution of deforming arthropathy, involvement of the proximal interphalangeal joint, metacarpophalangeal joint and the wrist (Fig 13.1, overleaf), Baker’s cyst of the popliteal fossa, and involvement of the upper cervical spine and the joints of the feet. Warm, tender and stiff joints may suggest active arthritis.

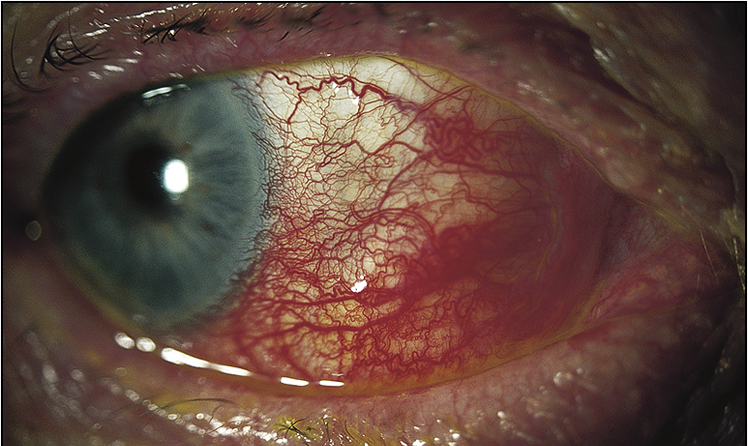

Assess the JVP and feel the precordium for a right ventricular heave. Auscultate the lung fields for fine crepitations of fibrosis. Listen to the heart for muffling of heart sounds due to pericardial effusion and loud P2 due to pulmonary hypertension. Palpate the abdomen, looking for splenomegaly. Perform a detailed eye examination and a neurological examination.

Hand examination is important. The following features should be looked for:

• radial deviation of the wrist

• ulnar deviation of the digits, swan-neck deformity and boutonnière deformity of the fingers, palmar subluxation of proximal phalanges

• ‘Z’ deformity of the thumb

• wasting of intrinsic musculature

• Tinel’s sign and neurological deficit in the distribution of the median nerve.

Assess the manual functional ability by asking the patient to pick up a pen and write their name, hold a cup, button and unbutton a shirt, and comb their hair.

Examination of the foot is also significant. Features to look for include:

Extraarticular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis

• Rheumatoid nodules in the elbow, Achilles tendon and the occiput (Fig 13.2)

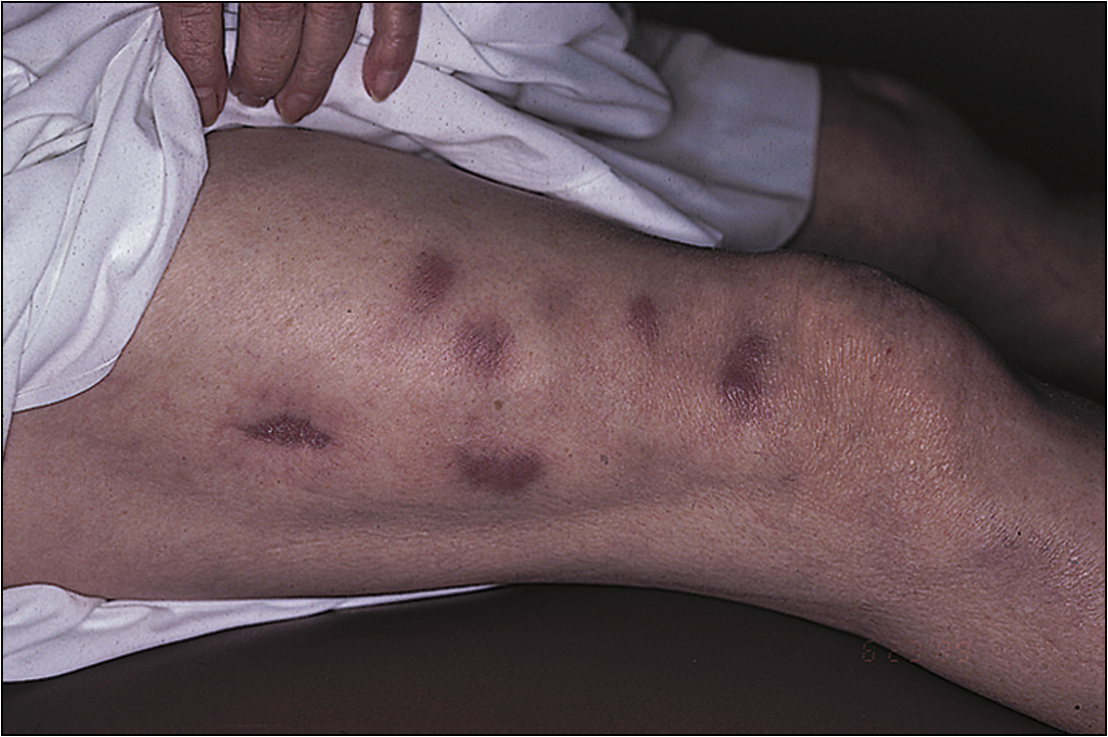

• Vasculitic features, such as nailfold infarcts (Fig 13.3), necrotic leg ulcers, mononeuritis multiplex

• Pleural effusion and bibasilar fine crepitations of pulmonary fibrosis (Fig 13.4)

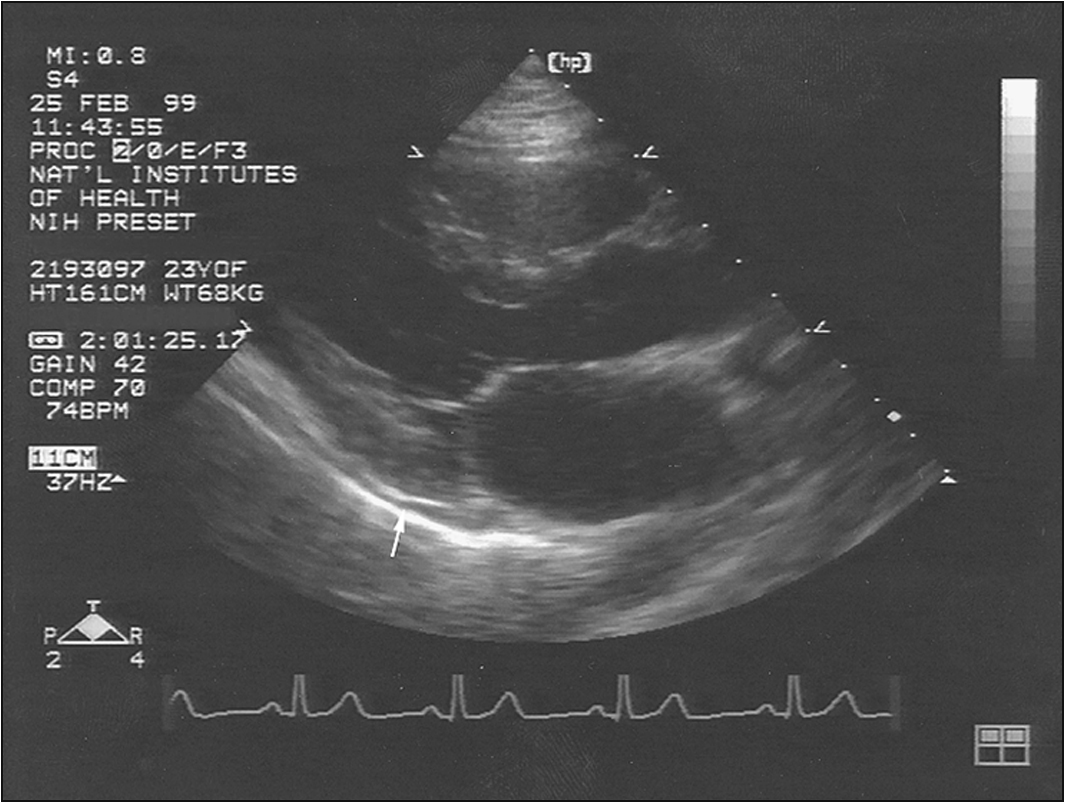

• Signs of pericardial effusion—elevated JVP, peripheral oedema etc (Fig 13.5)

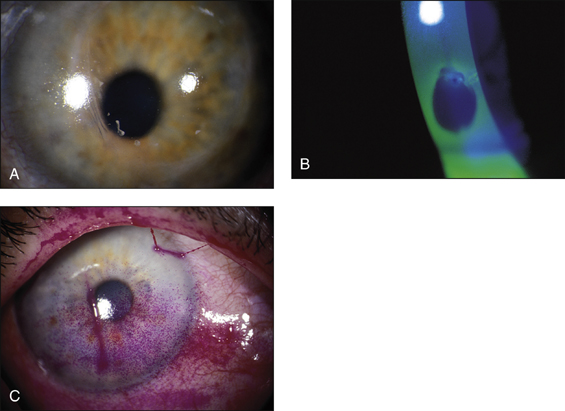

• Ocular signs of scleritis, episcleritis, scleromalacia perforans (Figs 13.6–13.8)

• Splenomegaly, if Felty’s syndrome is suspected

Investigations

1. Serum rheumatoid factor—this is present in only two-thirds of patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. It has more prognostic than diagnostic value, in that rheumatoid factor positivity is associated with more severe disease and the development of extraarticular manifestations. Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) haplotyping may have diagnostic and prognostic utility. Anti-CCP (anti-citrullinated cyclic peptide) is a very important disease-specific marker and may be detected several years prior to disease onset.

2. Full blood count—looking for anaemia of chronic disease or iron deficiency anaemia associated with NSAID therapy and/or thrombocytopenia and leucopenia of Felty’s syndrome. Anaemia and thrombocytosis correlate with disease activity.

3. Inflammatory markers such as ESR and C-reactive protein level—to monitor disease activity

4. Synovial fluid analysis—looking for features that suggest active arthritis, such as low viscosity, white cell count 20000–50000/mL with a predominance of polymorphs

5. X-rays of involved joints—looking for periarticular soft tissue swelling, joint deformity, joint space narrowing, juxtaarticular osteopenia, loss of articular cartilage and bony erosions, in chronic cases (Fig 13.9, overleaf)

6. Chest X-ray—looking for pleural effusion, rheumatoid nodules, features suggestive of pulmonary fibrosis and cardiomegaly suggesting pericardial effusion

7. Echocardiogram—looking for pericardial effusion, pulmonary hypertension (usually secondary), right heart strain and any suggestion of tamponade, which is a particularly rare phenomenon

8. Urine analysis—looking for proteinuria, and renal function indices looking for evidence of renal failure due to therapy-related toxicity

9. Liver function indices—looking for evidence of methotrexate or sulfasalazine toxicity

Management

Management of rheumatoid arthritis has three objectives: 1) control the symptoms, 2) optimise function and 3) retard progression.

Symptom control

This requires an interdisciplinary approach. Pain and stiffness can be managed with physical therapeutic modalities, antiinflammatory agents such as aspirin, NSAIDs, cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and parenteral glucocorticoid injections. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy is helpful in high-dose pulses at times of severe exacerbation and in low doses for the maintenance of remission. Severe deformity may need corrective surgery. The patient may need physical therapy for joint stiffness, and occupational therapy to improve functionality. Psychological and social help should be facilitated as required.

Disease-modifying agents

These drugs prevent disease progression and joint damage. They should be commenced early in the disease for maximum benefit. However, their onset of action is usually delayed by about 2–4 months. Some commonly used agents are as follows:

1. Methotrexate—given at weekly doses that vary between 7.5 mg and 25 mg per week. The maximum benefit may take up to 6 months to manifest. Patients should be monitored for the side effects of oral ulcers, hepatotoxicity, pneumonitis, lung fibrosis, anaemia and bone marrow suppression. Patients should be administered folic acid supplements concurrently. As this agent is teratogenic, female patients of reproductive age should take contraceptive measures while being treated.

2. Sulfasalazine (in male patients this agent can cause mild azoospermia)

3. Hydroxychloroquine—be aware of ocular complications

4. Gold

5. Leflunomide

6. Anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents play a major role in the management of rheumatoid arthritis—infliximab, an antibody against TNF-alpha, or etanercept, a soluble TNF receptor/Fc fusion protein. These agents are expensive and also have the side effects of tumour formation, sepsis and precipitating tuberculosis in susceptible individuals.

7. Anti-CD 20 agent—rituximab (selectively depletes CD 20+ B cells), for those not responding to anti-TNF therapy, usually given with methotrexate

8. T-cell modulator (costimulation modulator agent)—abatacept, for those not responding to anti-TNF therapy. Be cautious: in lung disease, it can worsen chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Combination therapy

Methotrexate can be given in combination with infliximab, etanercept or rituximab. Other effective combinations include methotrexate and leflunomide or methotrexate and sulfasalazine together with hydroxychloroquine. The latter triple combination is becoming popular.

SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Case vignette

A 55-year-old woman with a background history of systemic sclerosis presents with progressive exertional dyspnoea of 1 month’s duration. She complains of significant debilitation recently—she can barely walk up a flight of stairs without experiencing significant dyspnoea. On examination there is evidence of sclerodactyly and pitting scars on her fingerpads. Tightness and cutaneous fibrosis is also evident in her face, with loss of skin creases and microstomia. There is a parasternal heave. On auscultation of the precordium there is a significant systolic murmur and a loud P2. Fine crepitations are audible all over the lung fields.

Approach to the patient

There are two forms of this condition, according to the anatomical distribution of the disease:

Skin thickening (without organ disease) limited to two or three anatomical sites is termed morphoea.

History

Ask about:

• onset of symptoms

• duration and frequency of exacerbation—get the patient to describe the progression of the disease

• common symptoms—including swelling of fingers, forearm, feet and face, arthralgias, swelling and stiffness of the joints

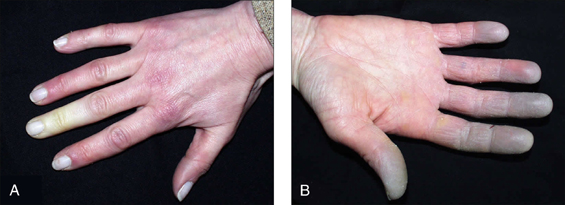

• symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon (see box and Fig 13.11)

• skin thickening, hardening and the formation of contractures

• upper extremity pain and numbness due to carpal tunnel syndrome and weakness of proximal musculature (consider overlap syndrome)

• dyspareunia in the female patient due to vaginal dryness

• reflux and dysphagia associated with oesophageal dysmotility syndrome

• weight loss and diarrhoea due to malabsorption associated with intestinal dysmotility and bacterial overgrowth

• respiratory symptoms of dyspnoea and cough

• progressive and debilitating exertional dyspnoea—may suggest pulmonary hypertension

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Raynaud’s phenomen is a combination of symptoms: digital pallor (due to vasoconstriction) followed by cyanosis (due to stasis) and subsequent hyperaemia (due to reactive vasodilation). This reaction is triggered by cold and relieved by heat. There may be associated paraesthesias and pain. In severe forms, digital infarction can occur. Causative associations include systemic sclerosis, SLE peripheral vascular disease, ergot, beta-blockers and smoking. When it occurs de novo it is termed Raynaud’s disease.

Examination

The patient may demonstrate the classic ‘bird-like’ facies and evidence of malnutrition and wasting. Examine the extremities for shiny muscle wasting and joint contractures. A patient who has developed renal failure may have an AV fistula or a vascular access device for dialysis. Observe skin changes of shiny tightness, hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, hair loss, dryness, telangiectasis and thickening etc. Perform a detailed hand examination, looking for nailfold infarcts, nail dystrophy, pulp loss in the fingers, sclerodactyly, calcinosis, evidence of carpal tunnel syndrome (confirm with Tinel’s sign) and arthritis. Facial signs found in systemic sclerosis include beak-like nose, microstomia, lack of wrinkles, flat affect and poor dental hygiene.

Perform a detailed joint examination, looking for changes similar to that in rheumatoid arthritis. Assess the degree of proximal muscle weakness and perform an abdominal examination, looking for distension and the absence of bowel sounds due to paralytic ileus. Respiratory examination may show bibasilar crepitations of pulmonary fibrosis. Check the blood pressure for hypertension. In the cardiovascular examination look for elevated JVP with a prominent Q wave, a parasternal heave and a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound, features that suggest the presence of pulmonary hypertension. Look for evidence of congestive cardiac failure due to cardiomyopathy, and features of chronic systemic hypertension. A 6-minute walk test is a functional assessment with prognostic significance.

Investigations

1. Full blood count—looking for anaemia, which could be multifactorial. The possible contributory causes are: anaemia of chronic disease, renal anaemia, gastrointestinal blood loss, vitamin B12 and folate deficiency due to malabsorption, and haemolytic anaemia due to microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA).

2. Serum protein electrophoresis, looking for hypergammaglobulinaemia.

3. Autoimmune serology—rheumatoid factor (this is positive in almost 25% of patients), ANA (positive in almost 95% of patients). Specific markers of systemic sclerosis, such as: antitopoisomerase antibody (Scl-70), anti-RNA polymerase antibody (predominant in diffuse disease), anticentromere antibody and antiribonuclear protein antibody (more prevalent in the limited disease).

4. Anti-PM/Scl (polymyositis/scleroderma) is a marker of the overlap syndrome with associated polymyositis.

5. Electrolyte profile and renal function indices—looking for evidence of renal failure.

6. Chest X-ray—looking for cardiomegaly, pleural effusion and features that would suggest pulmonary fibrosis.

7. High-resolution CT scan of the lung—looking for pneumonitis/alveolitis or fibrosis. Active alveolitis is amenable to therapy, and therefore classic CT findings may require confirmation with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or lung biopsy.

8. ECG—looking for left ventricular or right ventricular hypertrophy.

9. Transthoracic echocardiogram—looking for pulmonary hypertension and pericardial effusion. Right heart catheterisation with vasodilator challenge is indicated in patients with pulmonary hypertension.

10. Faecal fat quantification—looking for evidence of malabsorption.

11. Microscopy and culture of duodenal aspirate—looking for bacterial overgrowth.

12. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy—to exclude reflux oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagitis and peptic ulcer disease.

13. Oesophageal motility studies.

Management

Major objectives in the management of patients with systemic sclerosis are: 1) control symptoms, 2) improve functional capacity, and 3) treat organ-specific disease.

Skin thickening (in limited disease) may respond to UV rays, topical steroids or methotrexate; d-penicillamine therapy is no longer considered because of lack of supportive clinical evidence and substantial toxicity.

The fundamentals of medical management are as follows:

1. Topical and low-dose systemic corticosteroid therapy (with immunosuppressant combinations in resistant cases)—for skin, arthritis, myositis, pericarditis and early pneumonitis. Caution: Systemic steroids can precipitate renal crisis.

2. Physical therapy and avoidance of cold—for Raynaud’s phenomenon. Calcium channel blockers/ACE inhibitors provide symptom relief. Bosentan and iloprost may be useful too. Resistant cases may require surgical sympathectomy. Severe recalcitrant and painful limb ischaemia or infarction may require surgical therapy.

3. Proton pump inhibitors and prokinetic agents—such as erythromycin and metoclopramide, for oesophagitis and oesophageal dysmotility. Caution: These agents cause QT prolongation.

4. Bacterial overgrowth in the small intestines and malabsorption can be treated with rotating antibiotics. Severe cases may require parenteral nutrition. Intestinal pseudo obstruction may require surgical referral.

6. Low-flow oxygen is indicated for patients with persistent respiratory failure due to pulmonary fibrosis.

7. ACE inhibitor therapy is of significant benefit to the patient suffering from hypertension, proteinuria and renal failure.

8. Renal dialysis for patients with end-stage renal failure. Because the disease is complicated and systemic, these patients are not usually considered for renal transplantation.

9. Patients with pulmonary hypertension benefit from therapy with calcium channel blockers (those who respond to vasodilator therapy during right heart catheterisation), endothelin receptor blockers such as bosantan (oral), prostacyclins (IV or subcutaneous), and sildenafil.

10. Extreme disease may require referral for heart–lung transplantation.

11. Myocarditis is treated with low-dose corticosteroids and pericarditis with NSAIDs or corticosteroids when resistant.

Mixed connective tissue disease

This disorder manifests as an overlap of clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, polymyositis and rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-U1RNP antibody is a specific marker for this condition.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Case vignette

A 37-year-old woman presents with left-sided hemiparesis. She experienced sudden-onset weakness of the left upper limb and lower limb. The weakness has progressed over a few hours. She cannot identify any associated precipitating events. She denies headache or trauma. She denies smoking or illicit drug use. She has been married for 5 years and has had two pregnancies spontaneously aborted. Her background history is also remarkable for seizure disorder and distal upper extremity arthritis over a long period, during which she self-medicated with paracetamol. Her seizures have been controlled with valproate.

On examination she has 3/5 motor weakness at all levels in the upper limb and the lower limb on the left side. There is also sensory impairment to touch in the affected half of the body. The reflexes are diminished correspondingly. She also has an erythematous rash in the malar region bilaterally.

Approach to the patient

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem disorder with manifold presentations, and the severity may vary at different times.

History

Enquire about constitutional symptoms of lethargy, fatigue, fever and weight loss. Most patients suffer from arthralgias, myalgias, rash with associated photosensitivity and patchy alopecia. Ask about hip pain due to ischaemic necrosis of the head of the femur (usually due to high-dose steroids). Discoid skin lesions with scarring may suggest discoid lupus. Ask about seizures, psychotic episodes, headache and peripheral sensory impairment. Some patients may present with oedema due to nephrotic syndrome or dyspnoea and pleuritic chest pain due to pulmonary or cardiac involvement. Check whether the patient has had spontaneous abortions or recurrent thromboembolic disease (myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, pulmonary embolism, hepatic vein thrombosis). Some patients experience eye irritation and visual disturbance. Remember that antiphospholipid syndrome can also occur in isolation.

Take a drug history to exclude exposure to agents such as procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid, D-penicillamine and alpha-methyldopa, which are known to cause drug-induced lupus.

Examination

In the examination look for wasting or cushingoid body habitus.

A detailed joint examination should be performed, and the features to look for are spindle-shaped fingers and swelling and tenderness of proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal and wrist joints. Arthritis of SLE is usually non-deforming, but rarely a deforming but non-erosive form called Jaccoud’s arthropathy is seen. Examine the hip and knee joints for pathology.

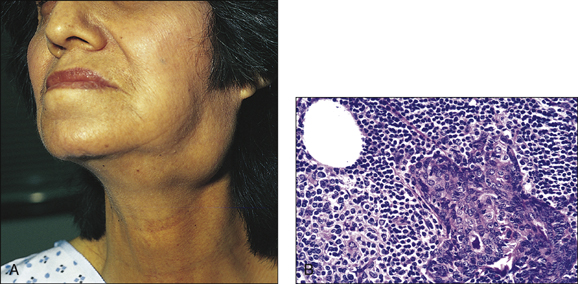

Note malar rash (butterfly rash), discoid lesions, scarring, patchy alopecia and panniculitis (Figs 13.12–13.15). Examine the eyes carefully. There will be conjunctival pallor, conjunctivitis, cytoid bodies and cataracts caused by steroid therapy. Note oral ulcers, lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly.

Neurological examination may reveal peripheral neuropathy and proximal weakness.

Cardiovascular examination may reveal features of pulmonary hypertension, cardiac failure or endocarditis (Libman-Sacks). In the respiratory tract examination, look for signs of pleural effusion and bibasilar crepitations of lung fibrosis. Do not miss oedema due to nephrotic syndrome and any lymphadenopathy.

Investigations

1. Full blood count—looking for anaemia, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia. Ask for a haemolytic screen, and iron studies if there is anaemia.

2. Autoimmune serology relevant to systemic lupus—such as antinuclear antibody titre, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody and anti-Sm antibody. The latter two are relatively specific for SLE. If there is a history of recurrent thromboembolism or fetal loss, check for the presence of antiphospholipid antibody, anticardiolipin antibody and the lupus anticoagulant.

3. C3, C4 levels and total haemolytic component (CH50)—these may be low, suggesting complement consumption. Some may have genetic complement deficiencies such as C1q and C2.

4. Electrolyte profile and renal function indices—looking for evidence of renal failure.

5. Urine analysis for proteinuria and haematuria, followed by urine microscopy—looking for red cell casts. If there is proteinuria, it should be quantified with a 24-hour collection.

6. Chest X-ray—for pleural effusion and features of fibrosis. High-resolution CT scan of the lungs to further characterise the pulmonary parenchyma.

7. Echocardiogram—looking for pericardial effusion and valvular vegetations.

Management

Management of SLE has three objectives: 1) control acute exacerbations and disease flare-ups, 2) control the symptoms of the chronic disease and 3) manage organ-specific diseases.

1. Inflammatory manifestations such as arthritis, myalgias and constitutional symptoms can be managed with NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors. Dermatitis and arthritis can be managed with antimalarial agents, such as hydroxychloroquine given in a dose of 400 mg/day for 3 months followed by a maintenance dose of 200 mg/day. This therapy should be carried out with annual review by the ophthalmologist to monitor for retinal toxicity. The patient should be advised to wear complete sun block to circumvent photosensitivity and prevent the resultant dermatitis or SLE flare-ups.

2. Severe disease is managed with high-dose systemic corticosteroids. Severe acute flare-ups, lupus nephritis and central nervous system involvement should be treated with 3–5 days of IV pulsed methylprednisolone in a dose of 500 mg/day. In the treatment of glomerulonephritis, addition of cyclophosphamide to corticosteroid therapy has been shown to be significantly beneficial. Mycophenolate mofatil, azathioprine, cyclosporine and methotrexate are other agents that have been useful in the treatment of these patients.

3. For patients who suffer from recurrent thromboembolic disease, lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin is indicated. The INR should be maintained at 2.5–3.5.

4. Psychological and social support, and physical and occupational therapy, should be incorporated into the overall management plan.

SJÖGREN’s SYNDROME

Approach to the patient

History

Ask about dry, gritty eyes and the details thereof. Fatigue is a very common complaint. Enquire about dry mouth, dental disease and difficulties associated with dysphagia and odynophagia. Patients may also have arthralgia and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Some patients may also have neurological complications such as peripheral neuropathy and poly- or mononeuropathy. Enquire about bladder symptoms. Ask about the onset of the disease and how it affects the patient’s daily life.

Examination

Look in the eyes for conjunctival desiccation and in the mouth for dry mucosae and decreased salivary pool. Examine the mouth closely for poor dental hygiene, buccal hypertrophy and dental caries. Feel the parotids, looking for tenderness and enlargement. Examine the extremities for weak distal pulse, cold peripheries and digital infarcts. Perform a detailed neurological examination. Check for lymphadenopathy. These patients can develop type I renal tubular acidosis, and they have a propensity to develop B-cell lymphomas.

Investigations

1. Full blood count—looking for anaemia and leucopenia

2. ESR—looking for elevation

3. Serum rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies (with speckled pattern), and anti-Ro (SSA)and anti-La (SSB) antibodies. Note that, in pregnant females, anti-Ro antibodies can cross the placenta and cause congenital heart block in the baby.

4. Serum amylase levels—looking for elevation. The clinical utility of this test, however, is dubious.

5. Serum protein electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis—looking for hypergammaglobulinaemia

MONARTHRITIS

Approach to the patient

Monarthritis can present as the sole complaint or as a comorbidity in a patient admitted for another pathology.

History

Ask about the onset and the progression of symptoms. Duration of symptoms should help distinguish between acute monarthritis and chronic monarthritis. Causes of acute monarthritis can differ from those of chronic monarthritis (see box). Check whether the patient has had previous episodes and, if so, ascertain the details of the diagnosis and the management. Enquire about precipitating and relieving factors such as alcohol, food with high purine content such as shellfish or offal. Check the medication list and ask about recent alcohol binges (gout). Ask about other associated conditions such as chronic renal failure, penetrating joint trauma, diabetes etc.

Examination

Perform a detailed joint examination without causing distress to the patient, who may have an inflamed, painful and swollen joint (Fig 13.19). Check the mobility of the joint, both active and passive. Check the temperature chart. Perform a systemic examination to identify other pertinent features such as gouty tophy, peripheral neuropathy etc.

Management

1. Consider septic arthritis until proved otherwise.

2. If there is a history of previous episodes that resolve spontaneously, a diagnosis of crystal-induced arthritis is likely.

3. Septic arthritis should be treated promptly with antibiotics upon joint washout.

4. Acute crystal-induced arthritis can be managed with analgesics, NSAIDs, corticosteroids or, rarely, colchicine.

5. Acute gout is treated with NSAIDs or colchicines. Allopurinol is given for long-term prevention once the patient has settled.

OSTEOARTHRITIS

Approach to the patient

History

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis. Patients usually present with chronic joint pain and loss of functionality or mobility. Osteoarthritis usually affects the feet, knees, hips, spine and hands, but other joints can also be affected, especially the shoulders, ankles and wrists. If there is involvement of uncommon sites (second, third metacarpophalangeal joints) think of secondary causes such as calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) or haemochromatosis. Ask about joint pain and transient morning stiffness, and evening stiffness. Ask what factors precipitate the pain. Secondary osteoarthritis can set in due to overuse or previous joint injury, and therefore it is important to enquire about such associations.

Check how the disease has been managed and any side effects associated with therapy. Ask about physical therapeutic modalities that have been tried and the success thereof. Ask about surgical interventions and joint replacements in detail. Some genetic associations have been identified, and so enquiring about the family history is of value. Ask how the arthritis and the pain and loss of mobility have affected the patient’s occupation and daily life.

Examination

Perform detailed examinations of the joints involved. Define the pattern of distribution of the disease. Assess joint movement actively and passively. In the hands, look for Heberden’s nodes in the distal interphalangeal joints and Bouchard’s nodes in the proximal interphalangeal joints. Feel for joint tenderness. Look for joint crepitus and also any evidence of joint effusion. Assess muscle strength to check for any muscle wasting.

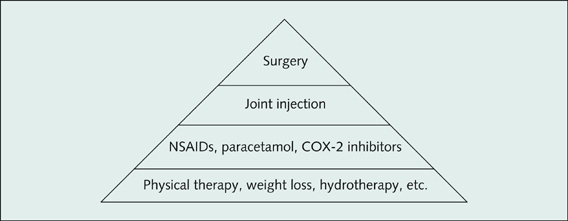

Management

1. Physical therapeutic modalities are very important in relieving joint pain as well as improving functionality.

2. Analgesics and NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors

3. Local injection of steroids or hyaluronic acid

4. Joint replacement surgery

5. Address the precipitating factors—weight loss etc.

Figure 13.20 Pyramid of therapy for osteoarthritis

Classification of osteoarthritis

1. Primary/idiopathic—age-related and may be associated with degeneration

2. Secondary—due to another pathology affecting the joints, such as:

• previous joint injury/insult

• joint instability (ligamentous laxity)

• congenital disorders

• diabetes

• obesity

• pregnancy

• haemachromatosis

• Wilson’s disease

• acromegaly

• hypothyroidism

• neuropathy—Charcot’s joint

• other joint disorders—calcium pyrophosphate crystal-induced arthritis (pseudogout), gout, Paget’s disease of the bone, rheumatoid arthritis