Chapter 16 Rheumatology

Long Cases

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

Major advances have occurred in the last few years regarding the understanding and the evidence base of JIA management. The escalation of chemotherapeutic agent usage and the evolution of biological therapies have transformed the outcome goals sought in JIA, where the expectation now is to be able to switch off inflammation, not just to control it. Early aggressive treatment that induces remission rapidly is now the aim.

Biological agents have enabled the management of JIA to evolve significantly in recent years. Trials of these agents in JIA have taken place through international collaborative efforts. Children with JIA are often used as long-case subjects, as their care is multifaceted and often difficult. The candidate should be well versed in the range of available drugs and newer biological agents employed, their important adverse effects, the role of physical and supportive therapies, the associated disorders and the long-term outcomes.

Current classification of JIA

Polyarthritis RF-negative

‘Polyarthritis RF-negative’ is defined as arthritis affecting five or more joints during the first 6 months after onset of the disease. This accounts for around 25% of JIA with female predominance, at any age. There is arthritis involving both the large and small joints of the upper and lower limbs, as well as the cervical spine and temporomandibular joints, and it may be symmetrical or asymmetrical. Uveitis may occur in approximately 10% and requires screening. ANA may be positive in over 25%. It can remit in late childhood, although continuation into adult life may also be seen. NSAIDs may be used to treat symptoms, whilst methotrexate is the agent of choice for maintenance of disease. Some patients may need higher doses of MTX, and as absorption of oral MTX may be variable and subject to first-pass metabolism by liver, parenteral administration may be required. Subcutaneous MTX is as effective as intramuscular MTX, but less painful and more likely to be adhered to.

Systemic arthritis

1. Early onset (1–4 years; peak at 2), equal sex incidence, up to 10% of JIA.

2. Systemic symptoms: fever (typically single or double quotidian pattern with high spikes daily, occurring at similar times every day); rash (evanescent, coming and going with fever spikes; discrete salmon pink macules 2–10 mm, usually around upper trunk and axillae; show Koebner phenomenon; rarely pruritic; not purpuric); polyarticular arthritis (can be late feature).

3. Other features: lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, serositis (pericarditis, pleuritis), and inflammatory ascites, haematological changes (anaemia, leucocytosis, macrophage activation syndrome).

4. An occasional feature is myocarditis.

5. Systemic features can precede arthritis by months. Natural evolution: systemic features followed by polyarthritis; this remains while systemic features regress.

6. Rheumatoid factor (RF) negative and usually antinuclear antibody (ANA) negative.

7. Approximately 50% remit in 2–3 years.

8. Untreated, joint destruction occurs in most cases.

9. Systemic arthritis is the only type of JIA without a specific age, gender or HLA association.

10. Most mortality from JIA is in this subgroup. Deaths can be due to infection secondary to immunosuppression, myocardial involvement or macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). MAS is a rare complication of systemic arthritis, involving increased activation of histiophagocytosis. Triggers include preceding viral illness (e.g. EBV) and additional medications (particularly NSAIDs, sulfasalazine and etanercept). Clinical findings include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, purpura, mucosal bleeding and multiple organ failure. Investigations may show pancytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, elevated fibrin degradation products, hyperferritinaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia and low ESR. Treatment involves pulse methylprednisolone and cyclosporine A, or dexamethasone and etoposide.

11. Uveitis is rare, although ophthalmological surveillance is necessary to detect cataracts or glaucoma as complications of steroid treatment.

The ILAR classification lists three criteria that are definite: (a) documented quotidian fever for at least 2 weeks, of which at least on three consecutive days a quotidian pattern has been recorded; (b) evanescent, non-fixed erythematous rash; and (c) arthritis. There are also criteria for probable systemic disease, in the absence of arthritis—criteria (a) and (b) above, together with any two of: generalised lymph node enlargement; hepatomegaly or splenomegaly; or serositis.

Psoriatic arthritis (JPsA)

JPsA has a female predominance and tends to occur in mid-childhood. The arthritis is frequently asymmetrical and may have oligoarticular onset, although a polyarticular course is commonly present. Dactylitis (sausage digits) is seen in younger patients and DIP joint involvement is common. The inflammation may involve tendon sheaths, and in its severe form cause ‘arthritis mutilans’, a very destructive arthropathy. There is often a family history of psoriasis. Fingernail pitting, onycholysis or other nail dystrophic changes may be seen. About half of the patients have the rash of psoriasis before the arthritis, whilst in the others the rash may present much later, or never at all. Few cases may develop both symptoms simultaneously. Uveitis can occur, and is seen in about 10% (chronic asymptomatic, as with extended oligoarthritis). Both ANA and HLA-B27 antigen may be present. Treatment of the psoriatic arthritis subtype is along similar lines as for other JIA subtypes, utilising intra-articular steroid injections for rapid control of acute inflammation, and other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for maintenance of the disease and prevention of relapse. Both methotrexate and steroids may not be as efficacious in the treatment of JpsA, and the use of TNF-α inhibitor may be indicated to prevent irreversible joint damage, or to reverse erosive changes.

Presentation of a long case with JIA

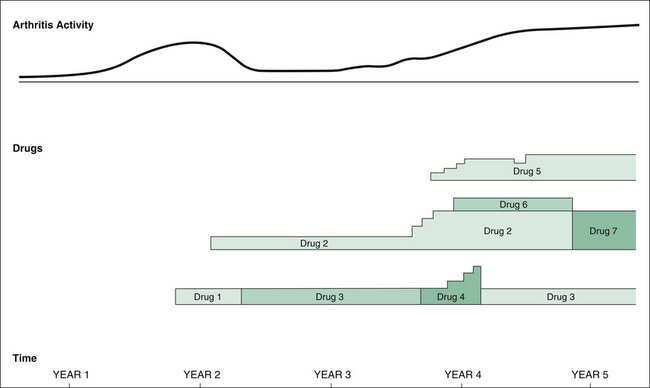

The child with JIA may have a very long and complicated history. Clarity of presentation to the examiners is essential. Long cases with JIA particularly lend themselves to pictorial display. This method can be used for recording the history and allows the examiners to appreciate clearly the progress of the illness. If the candidate wishes to try this technique, it should be practised on trial cases before the exam. Figure 16.1 demonstrates an example: a 15-year-old girl with difficult-to-control polyarthritis RF-positive JIA. The diagram shows progress over a 5-year period, with arthritis activity and drugs used. Investigation results can be shown on the same diagram.

History

Current symptoms

1. General health; for example, constitutional symptoms (fever, pallor, weight loss), exercise tolerance, quality of sleep.

2. Joint symptoms; for example, early morning stiffness, nocturnal discomfort/night waking, pain, tenderness, swelling, limitation of movement, problem joints (e.g. knees, hands), splints and orthoses used.

3. Level of functioning with activities of daily living (ADLs); for example, eating or pain on mastication, poor dental hygiene (limited jaw opening reflecting temporomandibular joint (TMJ) involvement), dressing, writing, walking, aids required (e.g. dressing sticks, adaptive utensils, wheelchair, computer), home modifications required (e.g. ramps, bathroom fittings), ability to attend/manage school, limitations of sporting and social activities, depression.

4. Skin rashes; for example, salmon rash of systemic JIA, malar flush (SLE), heliotrope of eyelids (dermatomyositis), psoriasis, rheumatoid nodules.

5. Chest symptoms; for example, pain from pleuritis, pericarditis.

6. Bowel symptoms; for example, diarrhoea with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

7. Eye problems; for example, uveitis, cataract, glaucoma.

8. Neurological symptoms; for example, seizures, drowsiness (JIA or SLE), personality change or headache with SLE.

9. Growth concerns; for example, short stature, delayed puberty, requirement for growth hormone, self-image effects.

10. Nutritional issues; for example, anorexia from drug side effects (e.g. methotrexate), cachexia persistent high inflammatory state, mechanical issues (TMJ involvement), bone mineral density (BMD) measurements (increased fracture risk with osteopenia [low bone mass for age, BMD between 1 and 2.5 SD below the mean for age and sex] or osteoporosis [BMD more than 2.5 SD below the mean for age and sex]), whether taking calcium or vitamin D supplements, muscle mass measurements.

11. Jaw involvement; for example, micrognathia, effect on self-image.

12. Drug/agent side effects; for example, steroid effects (poor height gain, obesity, myopathy), NSAIDs (GIT upset), methotrexate (leukopenia, hepatotoxicity).

Social history

1. Disease impact on child; for example, school absenteeism, limitation of ADLs, self-image.

2. Impact on parents; for example, financial considerations such as the cost of home modifications, splints, wheelchairs, transport, frequent hospitalisations, drugs.

3. Impact on siblings; for example, resentment from not getting enough attention/time from parents.

4. Benefits received; for example, Child Disability Allowance, Health Care Card.

5. Social supports; for example, Arthritis Foundation of Australia; internet resources used by parents.

Family history

Arthritis, autoimmune conditions, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, enthesitis, uveitis.

1. The patient’s current functioning (e.g. ADLs).

2. The patient’s current (and past) treatment modalities, such as physiotherapy, drugs and alternative therapies (e.g. naturopathic) tried.

3. The social situation (e.g. the child’s expectations for the future, and the geographical situation relative to the treating hospital).

Diagnosis

Although it is the most common chronic inflammatory arthropathy in children, JIA remains a clinical diagnosis of exclusion. Some of the diseases to be excluded are enumerated above. The diagnosis has been made categorically in patients used as long-case subjects. However, the candidate may be asked which investigations would have been appropriate when the child was initially seen. Thus, a differential diagnosis is worth considering, even in established cases, if only for possible discussion purposes.

Investigations

The following investigations may be helpful in JIA.

Blood tests

Serology

1. IgM rheumatoid factor (RF): 10% seropositive. Higher IgM RF titres carry a worse prognosis as regards permanent disability, and a greater likelihood of systemic features. The presence of CCP antibodies may add specificity to a positive RF test. Very high RF titres (>1000) may suggest SLE or MCTD to be the primary diagnosis.

2. Antinuclear antibody (ANA): positive in 50%, and mainly in oligoarthritis and extended oligoarthritis subtypes. Whilst the titre of ANA does not correlate with disease severity, by convention values ≥80 are regarded positive. Very high ANA titres (>1000) may suggest that SLE or MCTD is present.

Immunology

1. Immunoglobulins: all immunoglobulin types may be elevated as a hypergammaglobulinaemia response. The presence of specific Ig deficiency can cause arthritis, although this precludes diagnosis of JIA.

2. Complement: C3 and C4 may be elevated as a part of an inflammatory response, and a low C2 may occasionally be found (associated C2 complement deficiency), although deficiency in early complements may suggest diagnosis of SLE; raised alpha-2-macroglobulin.

Imaging

Management

The goals of JIA management are as follows:

1. Switch off inflammation, hence preventing permanent joint damage.

5. Treat complications and extra-articular manifestations.

1 Switch off inflammation

Local corticosteroid injections

Long-acting steroid preparations (e.g. triamcinolone hexacetonide) injected intra-articularly are safe, effective and useful for any joint with significant persistent inflammation. In particular, joints with flexion deformities (contractures) not responding to physiotherapy will benefit from this type of intervention. With successful treatment of joint inflammation, symptomatic treatment (e.g. NSAID treatment) may no longer be needed. Joint injections can be performed as a day case, using nitrous oxide inhalation or under conscious sedation for older children (over 8), or under general anaesthesia for younger children, for difficult-to-access joints (e.g. fingers, hips) or when multiple joints are being injected. Image intensification or ultrasound may be useful, particularly in the shoulders, hips and subtalar joints. For the TMJ, injection under CT or US guidance may be required, especially in patients with effusion or pannus evidenced on TMJ MRI. Paediatric rheumatologists are using intra-articular therapy much earlier in the treatment of JIA than previously, as there is evidence to show that this improves protection against erosions and will delay relapses. The positive effects of the steroid are noted usually within a few days, with effects usually lasting for several months. For those cases with recurrent synovitis, especially if a polyarticular course is present, simultaneous maintenance treatment (e.g. methotrexate) will be required.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

DMARDs are those medications that reduce the rate of adverse structural outcomes such as joint erosions. These include methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide, sulphasalazine (SSZ) and hydroxychloroquine. Their use is in (but not limited to) arthritis with a polyarticular course. DMARDs are continued until such time that the underlying disease activity is sufficiently low (remission), or if intolerance to them cannot be managed.

Corticosteroids

Systemic use

Pulse intravenous steroids are used when a rapid therapeutic effect of the systemic steroids is required. Examples may include pericardial or pleural effusion, or macrophage activation syndrome in systemic arthritis. The latter is a complication in systemic arthritis, or indeed any other connective tissue disease with persistently high inflammation, and if left untreated will cause multi-system failure and death. In addition to steroids, a maintenance agent, usually cyclosporine, will be required. The treatment regimen consists of IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg [up to 1 g maximum dose] as an infusion given over 1–2 hours for three consecutive days. Repeating this schedule a week later may be associated with less recurrence.

Biological agents

Etanercept (ETN) (recombinant p75 soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor (sTNFR): Fc fusion protein)

When effective, etanercept causes significant reduction in disease activity within 2 weeks of commencement, with sustained benefit as long as treatment is continued. In JIA with a polyarticular course, it controls pain and swelling, improves laboratory parameters and slows radiographic progression of the disease. The drug is named to indicate that it intercepts TNF-α, a cytokine important in the pathogenesis of RA and JIA. It is made up of two components: the extracellular ligand-binding domain of the 75kD human receptor for TNF-α, and the constant portion of human immunoglobulin (IgG1): hence the term ‘fusion protein’. There is a low serious adverse event rate. Up to 8 years continuous therapy with ETN has demonstrated no cases of opportunistic infection or malignancies.

Other biological agents

• Abatacept (CTLA4-Ig) is a fusion protein made up of the extracellular domain of human CTLA4 (a second receptor for the B-cell activation antigen B7) and a fragment of the Fc portion of human IgG1 (hinge and CH2 and 3 domains), and binds human B7 (CD80/86, on antigen-presenting cells) more strongly than CD28 (on native T cells). It targets T-cell activation, and inhibits T-cell proliferation. It has been used successfully in patients who fail to respond to TNF inhibitors.

• Adalimumab also is a monoclonal anti-TNF-α antibody, but it is completely humanised, and it is given by SC injection every 2 weeks. Early studies suggest that it may be useful in the treatment of JIA with a polyarticular course. It is especially efficacious when MTX is given concurrently.

• Anakinra is a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, which may be useful in recalcitrant systemic arthritis, where it has a response rate approaching 80%.

• Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal anti-TNF-α antibody, which binds to soluble TNF-α and its precursor, neutralising their action. In Australia, it has TGA approval for use in paediatric Crohn’s disease. It may be as efficacious as etanercept in treating JIA with a polyarticular course, although head-to-head studies have not been conducted. It is given intravenously. A higher dose of infliximab, at a level of 6 mg/kg, has a better safety profile than the dose used in the initial studies (3 mg/kg); it is given at time 0, 2 and 6 weeks, then every 6–8 weeks.

• Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that targets cells bearing CD 20 surface markers, depleting the B-cell population. It has been used in conjunction with MTX in patients who are resistant to TNF inhibitors.

• Tocilizumab is a humanised anti-interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor antibody, which almost completely blocks transmembrane signalling of IL-6. IL-6 is the key cytokine in the pathogenesis of systemic arthritis. It appears promising in the therapy of recalcitrant systemic arthritis, used at a dose of 8 mg/kg. It leads to significant improvement in disease activity indices, and a decrease in acute phase reactants. Adverse reactions can include anaphylactoid reactions, bronchitis and gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)

This has been performed in recalcitrant systemic arthritis. Remission can occur, but there is a significant mortality rate, usually from macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). It should only be considered if all other treatment options have failed. Long-term effects are not known. Several deaths, as a complication of an HSCT for JIA, have been recorded, related to MAS; many rheumatologists would not consider the procedure because of the inherent risks.

Sequence of drugs/agents

1. For life-threatening systemic arthritis, pulse corticosteroids are the agents of choice. MTX is simultaneously started as a maintenance agent, which in time will allow reduction in the amount of oral systemic steroids used (hence the term ‘steroid-sparing agent’ used for MTX). If MTX is unsuccessful, leflunomide can be tried, although if the disease severity is significant, commencement of biological agents may be indicated. Although etanercept is the only PBS-listed biological agent, others may be available by application to the hospital drug committees or local health authorities, usually if treatment with etanercept has failed.

2. For non-life-threatening and non-systemic disease, try the following sequentially:

2 Provide analgesia and treat stiffness

Morning stiffness

1. A warm bath/shower or hot packs may be helpful.

2. May be seen the morning after a particularly physical and busy day (e.g. school sport).

3. Treat with nocturnal, longer-acting, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g. dispersible piroxicam, naproxen, indomethacin), or by taking a morning dose of shorter-acting types (e.g. ibuprofen).

3 Maintain joint function

1. Physiotherapy (including hydrotherapy) to maintain the joint range of movement (ROM) (e.g. stretching), muscle strength (exercise) and gait education. Particularly useful types of activity that help joint range and strength are walking, cycling and swimming, which need to be done at least 4–5 times during the week.

2. Attention to footwear (e.g. sports shoes with a supportive arch are comfortable and often appropriate) or wearing custom-made orthotics for leg length discrepancy or deformities (e.g. genu valgus, from epiphyseal overgrowth; measure the intermalleolar distance to monitor this).

3. Even in the presence of acute synovitis, active physiotherapy is encouraged to minimise muscle wasting and to maintain joint ROM. Hydrotherapy may be particularly useful, as the warm water promotes better mobility, and the buoyancy reduces the required power to move the body.

4. Occupational therapy assistance for those with upper limb involvement, particularly for wrist and hand involvement. This assists with fine motor movement, and ADLs such as dressing, feeding and toileting, as well as for writing and use of a keyboard.

4 Prevent deformities

2. Insoles and medial arch support (for hindfoot valgus).

3. Prone lying (for hip/knee contractures in particular).

4. Nocturnal traction (especially for hip pain).

5. A cervical collar (for torticollis, pain, occipito-atlanto dislocation, and before general anaesthesia requiring intubation).

6. Surgical intervention may be needed where conservative treatment has failed to prevent deformity. Possible interventions include soft-tissue releases (e.g. for fixed flexion deformities at hips or knees), stapling (e.g. of medial femoral and tibial epiphyses to correct valgus deformity), osteotomy and fusion/arthrodesis. Synovectomy (surgical or radioactive) may be occasionally needed for persistent pain and swelling (e.g. hips, knees). Total joint replacement may be offered to individuals with severely damaged joints who have an unacceptable level of pain or functional loss, although with modern treatment fewer and fewer patients will need this.

5 Treat complications

Eye involvement

1. Chronic uveitis: all patients need regular uveitis screening by a trained ophthalmologist; 3–4 monthly for those at higher risk, and 6–12 monthly if the risk is lower.

2. Active uveitis is usually treated with steroid eye drops and mydriatics.

3. MTX has a therapeutic effect on uveitis.

4. The anti-TNF agents infliximab and adalimumab are efficacious in controlling uveitis. Etanercept has occasionally been held responsible for exacerbation or evolvement of uveitis.

7 Rehabilitation

Occupational therapy

1. School: use of adaptive pencil holder, standing desks, ramps, decreasing inter-class distances, avoiding stairs, potential for use of laptops in place of writing.

2. Home: dressing sticks and hoops, large buttons, Velcro fasteners, adaptive utensils, hand-held shower, use of computers, tape recorders (if writing difficult).

9 Educate parents and patient regarding disease

1. Ensure adequate understanding by parents, patients and siblings of the disease, treatment, drug side effects, importance of compliance and prognosis.

2. Encourage contact with reputable consumer groups (e.g. Arthritis Australia) and suggest trustworthy websites.

3. Dispel myths and false beliefs (e.g. held by other, older family members) regarding JIA, drugs used and alternative therapies (unproven therapies that are popular [despite no data in existence to support their use], including glucosamine and hyaluronic acid).

Juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (JIIMs): juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM)

The IIMs of childhood are rare diseases, but are not uncommon in examination settings.

Background

1. Characteristic rashes. Two are pathognomonic: (a) Gottron’s papules—scaly red papular areas over the knuckles (MP) and IP joints [papules can also overlay elbows, knees and malleoli]; (b) heliotrope rash—a violaceous or purplish, with somewhat oedematous discolouration around the eyes, particularly over the eyelids (capillary telangiectasia), which may cross the nasal bridge and include the nasolabial folds. Other rashes encountered include scaly red rash on the sun-exposed areas; the face, neck and upper chest (V-sign), the shawl area (shawl sign) and over the extensor tendons, particularly of the hands (linear extensor erythema). Commonly there is an erythematous rash involving extensor surfaces (elbows, knees), which may be mistaken for psoriasis.

The other criteria, of which three out of four are required, are as follows:

2. Symmetrical proximal muscle weakness (although in practice distal muscles, as well as the oropharynx are also involved).

3. Elevated muscle-derived enzymes (creatine kinase [CK], aldolase, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] and transaminases [AST and ALT]).

4. Muscle histopathology confirming the typical pattern of myofibre atrophy and drop out necrosis with fibre regeneration, and chronic inflammatory infiltrate involving blood vessels.

5. Electromyography (EMG) changes of inflammatory myopathy (fasciculations at rest, bizarre high-frequency discharges). EMG interpretation is dependent on appropriate placing of the electrode in areas of inflammation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to select the sample site (inflammatory muscle involvement causes non-uniform changes in muscle, abnormal increased signal on T2-weighted images and normal signal on T1).

Note that recently MRI has been used more often to detect skin, fascia and subcutaneous abnormalities, as well as muscle inflammation, which can be helpful in clarifying the extent of involvement in difficult cases, therefore aiding with devising a management plan. MRI is likely to replace the more painful, invasive tests of muscle biopsy and EMG, and become one of the diagnostic criteria.

At diagnosis, all children have weakness and rash, and are universally reported to be irritable. Anasarca (severe generalised tissue oedema) and skin ulceration are signs of severe disease and call for aggressive treatment. Most have muscle pain and fever, and 20–50% have dysphagia or hypernasality of voice, abdominal pain and/or arthritis. Soft-tissue calcification (calcinosis) is seen in 30–70% of patients eventually, in sites exposed to trauma (buttocks, knees, elbows) and seems to reflect the severity and duration of disease; it is relatively rare at diagnosis. The mechanism of calcinosis is thought to be due to damaged muscles releasing mitochondrial calcium into matrix vesicles that promote mineralisation. Calcinosis is related to hydroxyapatitie accumulation; it can occur as superficial lumps, plates along fascial planes or widespread exoskeleton distribution. Calcification can resolve spontaneously, and drain a white exudate, leaving pitted scars. Abscess formation may be seen in the muscles and become infected with Staphylococcus aureus. Calcification can persist in fibrotic muscle in sheath-like forms, impairing function. Both the skin and the muscle manifestations may be precipitated or exacerbated by sun exposure.

Other manifestations include the following:

1. Vasculitis involving the central nervous system (causing seizures and organic psychosis—even fatal brainstem infarction has been described).

2. Ophthalmological complications include retinopathy (retinal exudates, ‘cottonwool’ spots, optic atrophy, visual impairment), glaucoma (from steroids) and cataracts (from steroids).

3. Renal tract: renal failure secondary to myoglobinuria from muscle breakdown; ureteral (middle third) necrosis secondary to vasculopathy.

4. Reproductive system: active disease can delay menarche, interrupt menses or adversely affect pregnancy outcomes.

6. Lipodystrophy: this is a slowly progressive symmetrical loss of subcutaneous fatty tissue that typically involves the upper half of the body; mainly in females; it can be associated with acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, hepatomegaly, hyperlipidaemia (especially hypertriglyceridaemia) and insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus; the pathophysiology is unknown.

7. Juvenile polymyositis (JPM) is identical to JDM but without the skin rash. It is exceedingly rare.

History

At the completion of presenting the history, the examiners should have a clear impression of the patient’s current functioning (e.g. ADLs), current (and past) treatment modalities (such as physiotherapy, drugs and alternative therapies [e.g. naturopathic] tried) and social situation (e.g. transport issues, distance from home to treating hospital).

Current symptoms

1. General health (e.g. fever, weight loss, nutritional status).

2. Musculoskeletal symptoms; for example, general pain or tenderness, asthaenia, muscle weakness, cramps, joint symptoms (early morning stiffness or gelling after inactivity, nocturnal discomfort, pain, tenderness, swelling, limitation of movement [contractures or calcinosis of tendon sheaths], problem joints), contractures and the requirement for serial casting.

3. Skin rashes; for example, heliotrope of eyelids, Gottron’s papules (knuckles), photosensitive rashes, scarring and atrophy.

4. Calcinosis; for example problem areas (e.g. buttocks, extensor surfaces).

5. Level of functioning with activities of daily living (ADLs); for example, speech (tongue involvement), eating (chewing difficulties from involvement of muscles of mastication), swallowing (soft palate weakness, abnormal oesophageal motility), sitting (buttock soft-tissue calcification), walking, negotiating stairs, squatting, assistance devices (e.g. adaptive utensils, wheelchair, computer) and home modifications required (e.g. ramps, bathroom fittings).

6. Gastrointestinal (GIT) symptoms: oral, upper GIT and lower GIT (e.g. ulceration, perforation, haemorrhage, malabsorption).

7. Genitourinary symptoms; for example, discoloured urine (episodes of myoglobinuria), renal impairment, ureteral involvement and interference with menstruation.

8. Eye problems; for example, visual impairment, retinopathy, glaucoma and cataracts.

9. Neuropsychiatric symptoms; for example, mood swings and depression.

10. Drug side effects; for example, steroid effects (Cushing’s syndrome, stunted linear growth, myopathy), cytotoxics (e.g. myelosuppression, opportunistic infection, hepatotoxicity [MTX], hypertension [CPA]) and IVIG (infusion-related toxicities, other IVIG complications such as aseptic meningitis, thromboembolism).

11. Other systems review; for example, cardiopulmonary symptoms, Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Social history

1. Disease impact on: (a) child (school absenteeism, limited ADLs, poor self-image); (b) parents (financial considerations: home modifications, wheelchairs, computers, transport, frequent hospitalisations, drugs); (c) siblings (rivalry).

2. Benefits received; for example, Child Disability Allowance.

Management

First-line treatment

There is a paucity of randomised controlled trials for treatment choices in JDM. Corticosteroids (CS) are needed in relatively high doses to restore muscle power as quickly as possible, whilst commencement of a maintenance agent (e.g. MTX) will allow weaning the steroids later and helps with controlling the skin rash. Physiotherapy is started as early as possible, and other allied health professionals, such as a speech therapist, may be needed to assess the aspiration risk. The use of steroids has reduced the mortality in JDM from 40% to 3%, although with modern treatment this rate is probably even lower. It is likely that residual disability and the extent of calcinosis have been diminished by CS as well (although CS can occasionally cause muscle weakness, osteoporotic fractures and avascular necrosis, which can adversely affect disability). The oral prednisolone/prednisone dosage is usually 1–3 mg/kg per day, although doses larger than 1 mg/kg are associated with far greater side effects without much additional therapeutic benefit. The aim of the treatment should be to start weaning the CS dose as soon as the patient’s clinical condition allows, to minimise side effects. Oral steroids are given as a morning dose to minimise their impact on growth, and alternate day doses must be avoided to reduce the possibility of relapse. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulses (IVMP) are used if the overall disease severity is deemed high, or if there is incomplete response to oral corticosteroids. Aggressive induction of therapy, including the use of IVMP, seems to lead to less relapsing disease, residual weakness or calcinosis. IVMP also may be useful for treating serious complications such as myocarditis or dysphagia, as well as for treating the skin manifestations. High-dose IVMP is a potent immunosuppressive agent, and meticulous attention needs to be given to the possibility of developing infections, with aggressive treatment of the same required. During the infusion, side effects may include flushing, headache, a metallic taste in the mouth and hyper/hypotension, requiring measurement of vital signs every 15 minutes.

Methotrexate (MTX)

Cyclosporine (CSA)

C. Compromised kidneys (nephrotoxicity includes irreversible vasculopathy, interstitial fibrosis, tubular damage)

S. Secondary malignancy potential (especially lymphoproliferative)

A. Anaemia/Accelerated blood pressure (hypertension), hair growth (hypertrichosis) and gums (gingival hyperplasia)/Additional myopathy (caused by CSA per se; this can contribute to osteoporosis)

Biological agents

Those already tried in JDM include the tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors etanercept and infliximab, and the B-cell depleter rituximab. Biological agents are increasingly being trialled in children with severe disease that is refractory to standard therapy. For more details about these agents, see the long-case section on JIA.

Prognosis

The mortality rate has been quoted as 3%, although this is probably lower with modern therapy and an aggressive approach. Morbidity is relatively high, especially from delay of treatment, or from medication side effects. Treatment should generally be continued for a couple of years for consolidation and maintenance, although in individual cases this may be shortened (monophasic disease in adolescents). A periungal capillary count of <3 per mm is associated with relapse if treatment is withdrawn.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

History

Symptoms

1. General (anorexia, malaise, pallor, weight loss, fatigue).

2. Skin (malar rash [in 33%], purpura), mucous membrane (palate ulcers), hair loss or scalp ulceration.

3. Joints: symmetrical polyarthritis, usually non-erosive (Jaccoud type of arthritis; reversible subluxation due to tenosynovitis) may present with morning stiffness, pain and swelling.

4. Cardiovascular (Raynaud’s phenomenon, cardiac failure symptoms due to myocarditis, chest pain from serositis or, less likely, myocardial ischaemia).

5. Respiratory (recurrent chest infections, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea).

6. Renal (hypertension, oedema, haematuria).

7. Neuropsychiatric (headache, cerebrovascular disease, seizures, chorea, personality change, decreased school performance, depression, suicidal ideation, acute confusional state, anxiety, cognitive dysfunction, psychosis [occurs in 50% of patients with neuropsychiatric involvement]).

8. Abdominal pain (e.g. serositis, pancreatitis).

9. Menstrual abnormalties (due to SLE per se or steroids).

11. Drug effects (e.g. steroid effects: Cushing’s syndrome, hypertension, poor height gain, myopathy, osteoporosis (± fracture or vertebral body collapse), avascular necrosis (AVN), especially hips and knees.

Examination

The procedure outlined here would also be suitable for a short-case approach.

General observations

2. Pallor (anaemia; various mechanisms).

3. Cushingoid features (steroid treatment).

4. Parameters: height (e.g. short due to steroids); weight (e.g. obese due to steroids).

6. Joint swelling, gait problems.

7. Peripheral oedema (renal disease).

8. Posturing (e.g. hemiplegic).

9. Involuntary movements (e.g. chorea, hemiballismus, tremor, parkinsonian-like movements).

10. Respiratory distress (e.g. pneumonitis, pulmonary oedema).

11. Impression of mental state (e.g. depressed, or difficulty concentrating, with neuropsychiatric involvement).

Neurological and eyes

Cranial nerves

Test motor cranial nerves (mononeuritis multiplex; trigeminal neuropathy, facial nerve palsy, extraocular muscle weakness). Look for nystagmus (cerebellar involvement). If the child has focal deficits, also check the visual fields (e.g. for hemianopia). Inspect for episcleritis. Ophthalmoscopy: check for cataracts (steroids); retinal cottonwool exudates, haemorrhages.

Investigations

• Antinuclear antibodies (ANA): up to 100%.

• Anti-U1 RNP antibodies (an RNA-binding protein): 70–90%.

• Anti-DNA antibodies: 60–70%.

• Anti-cardiolipin (aCL) antibodies (antiphospholipid antibodies): 50%.

• Anti-Sm antibodies (another RNA-binding protein): 40–50%.

• Lupus anticoagulant (LAC) antibodies (antiphospholipid antibodies): 20%.

Simple screening tests

1. Haemoglobin (e.g. haemolytic anaemia; relative macrocytosis, or normocytic anaemia of chronic disease).

2. White cell count (e.g. leukopenia).

3. Platelet count (e.g. thrombocytopenia).

4. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA), directed against a number of autoantigens. This is one of the hallmarks of SLE. This is the best simple screening test. Be aware that persistently positive ANA in the absence of other objective evidence of rheumatic disease does not suggest a chronic rheumatic disease by itself. The vast majority of ANA-positive children do not have SLE. At least 10% of the normal paediatric population are positive for ANA.

5. Inflammatory markers: ESR is typically elevated in the presence of a normal CRP. If the latter is elevated, infections must be meticulously searched for.

6. Urea, creatinine, electrolytes (to assess renal function).

More specific tests for pSLE

Blood

1. Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies (relatively specific to SLE; correlates with more severe systemic involvement, e.g. renal disease); DNA–Farr (radioimmunoassay); DNA–Crithidia titre (immunofluorescence). DNA binding is also useful. dsDNA may be useful in disease monitoring; for example, renal or CNS disease.

2. Antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens (e.g. Ro [SSA], La [SSB], Sm, RNP). Antibodies to Ro and La are associated with neonatal lupus, and occur with increased frequency in children of mothers with SLE. Antibodies to Sm are very specific for patients with SLE: they are found in about two thirds of SLE patients.

3. CH-50, C3, C4 (usually low values in active disease). C3 and C4 are useful in monitoring disease activity. Isolated deficiencies (e.g. C2) may be found.

4. Coomb’s (direct antibody) test (e.g. positive with immune-mediated anaemias).

5. Clotting profile (e.g. prolonged PTT with circulating lupus anticoagulant; paradoxically, a tendency for thrombotic events in vivo).

6. Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL): includes anticardiolipin antibody (aCL) and lupus anticoagulant (LAC). Associated with recurrent thromboembolic events.

7. Liver function tests (raised enzymes in salicylate hepatotoxicity or active SLE).

Imaging

1. Chest X-ray (e.g. pneumonitis, myocarditis).

2. Bone X-rays (e.g. vertebral collapse).

3. Neuroimaging (all but MRI scan are research tests so far):

4. Cardiac imaging: echocardiography—M-mode, two-dimensional, Doppler and/or transoesophageal (endocarditis vegetations, mural thrombi, other cardiac source for emboli).

Other

1. Renal biopsy is indicated if significant abnormality is detected in the urinalysis. Many children with SLE will have a renal biopsy. The vast majority of children with SLE have some form of renal disease. Various forms of glomerulonephritis (GN) can occur; for example, mesangial GN, focal and segmental proliferative GN, diffuse proliferative GN (DPGN), membranous GN and mixed patterns.

2. Pulmonary function testing (e.g. interstitial lung disease).

3. Neuropsychological assessment (for children with neurological involvement; there is some evidence that this may be the best test for CNS lupus).

Management

The treatment goals are as follows:

1. Control disease activity (prevent and suppress disease flaring) to restore health towards normal.

2. Prevent scarring of organs (e.g. kidneys, brain).

3. Minimise adverse drug side effects (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome).

General measures

Preventative management for osteoporosis may include adequate exercise, a high calcium intake and adequate doses of vitamin D.

1. The occurrence of the ‘postpartum backlash’; that is, relapse of the disease.

2. The SLE association with increased miscarriage, and neonatal lupus with congenital heart block (see later).

3. Pregnancy must be carefully planned—that is, with blood pressure, renal disease and haematological indices under control—and is best timed when in remission, or stable for over 12 months.

Main agents used

Corticosteroids

The side effects of steroids are well known and already alluded to in the section under JIA treatment. Children generally develop Cushingoid features if they take over 0.25 mg/kg prednisolone per day for over a month. A radioreceptor assay can measure steroid activity (plasma prednisolone equivalents). Catch-up growth after cessation of treatment may not be complete, as chronic disease may also compound growth failure. Children who have had more steroids are more likely to develop more significant sepsis.

Approach to treatment of specific system involvement

Kidneys

Renal involvement in SLE is as follows (simplified schema of WHO classification):

WHO class I Normal light microscopy

WHO class II Mesangial lupus nephritis (around 20% of cases)

WHO class III Focal proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN) (around 20% of cases)

WHO class IV Diffuse proliferative GN (just under 50% of cases)

Treatment is based on renal histology. Severe renal involvement requires intensive and prolonged treatment. Steroids (high-dose oral prednisone, or pulse intravenous doses of methylprednisolone, if required) and cytotoxics as above are often needed:

• WHO class II: low-dose steroids—short course, slow taper, excellent outcome. Some nephrologists use angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blocking agents (ARBs) alone, to decrease proteinuria.

• WHO class III and IV: high-dose steroids—slow taper, add second agent after biopsy to confirm histology. Second agent: MMF, AZA or CPA. MMF and AZA are safer. Class IV usually responds to steroids. For active SLE complicated by class IV, intravenous (IV-) CPA may be indicated. One effective regimen used monthly IV-CPA for 7 months, then IV-CPA every 3 months for the next 30 months. As the CPA-related toxicity is cumulative, there is a recent trend to use only 6 once-monthly CPA pulses as induction, and concomitant use of cytotoxics for maintenance. With this treatment, many children have exhibited marked improvement in their overall well-being, including a decrease in infection, cerebritis, arthritis and emergency hospitalisation. If nephrotic syndrome occurs, AZA may be useful.

• WHO class V may well respond to low-dose steroids. Some patients require prolonged steroids, then CSA, AZA or MMF. ACE inhibitors or ARBs are used as well to decrease proteinuria. Anticoagulation may be required, due to the risk of renal vein thrombosis, and possible pulmonary embolism.

Children who receive RTx have a better prognosis than those on dialysis (see the section on RTx in Chapter 13, Nephrology). Those children with poor prognostic factors are treated aggressively, and those with ESRD have transplants as soon as possible.

Cardiovascular

The main cardiovascular system morbidity in pSLE is premature atherosclerosis. The most common cardiac manifestation is pericarditis with pericardial effusion. Other forms of involvement include endocarditis and myocarditis, which can be treated with steroids. Pericarditis can respond to NSAIDs alone. Valvular heart disease can occur, in association with aPL antibodies or with non-infective endocarditis. Libman–Sacks verrucous endocarditis can occur in acutely ill children with pSLE. The most commonly affected valves in order (left two, then right two) are as follows: mitral, aortic, pulmonary, tricuspid. There is an inflammatory infiltrate first, then the formation of nodules of fibrinoid necrosis of the supporting connective tissue of the valve. Treatment may involve high-dose steroids, cytotoxics or surgery. The main cardiovascular morbidity, however, is premature atherosclerosis. The main risk factor for this is ongoing chronic inflammation of pSLE itself. Steroids could theoretically make atherosclerosis worse. Most children with SLE will develop significant dyslipidaemia, which increases their risk of atherosclerosis in later life. Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine have an advantage of lipid-lowering among their many effects. Input from dieticians and physiotherapists will help avoid high blood lipid levels and obesity, and will help optimise physical exercise. In North America, the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) has launched the Atherosclerosis Prevention in Pediatric Lupus Erythematosis (APPLE) prospective study, assessing the role of statins in the prevention of atherosclerosis—the largest prospective study ever undertaken in pSLE.

Skin

Avoid sun exposure wherever possible. Adopt appropriate clothing and the use of sunscreen (with a sun protection factor at least 30), topical steroids for discoid lesions, and oral agents (hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, with or without low-dose steroids). Raynaud’s phenomenon is less common in paediatric than in adult SLE: management is by avoidance of cold exposure, appropriate clothing (e.g. insulated mittens [rather than gloves]; multiple layers of clothing; hats, hand and feet warmers) to keep extremities warm, low-dose aspirin (if there is no thrombocytopenia) and, if these are inadequate, oral nifedipine or low-dose steroids, or topical nitroglycerine paste.

Neonatal lupus

Adolescent girls with pSLE contemplating having children need to be fully aware that babies of mothers with SLE can develop features of SLE. Transient features are entirely due to transplacental passage of maternal antibodies, as they resolve with clearance of the antibodies. Examples include thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, myocarditis, pericarditis and the photosensitive discoid skin rash. The other group of features are permanent, their aetiology being only partially explained by transplacental antibody passage. Examples include congenital complete heart block (CCHB; associated with antibodies to SSA/Ro [particularly to the 52 kD Ro polypeptide rather than the 60kD Ro] and SSB/La), endomyocardial fibroelastosis and other forms of structural heart disease. Fetuses with congestive cardiac failure, CCHB and pericardial effusions have been treated with some success by giving the mother dexamethasone.

Short Case

Joints

This is not an infrequent case. The approach given here has three basic components:

1. Thorough general inspection.

2. Systematic examination of all joints.

3. Examination for extra-articular manifestations of JIA and other diseases affecting joints, plus detection of drug side effects.

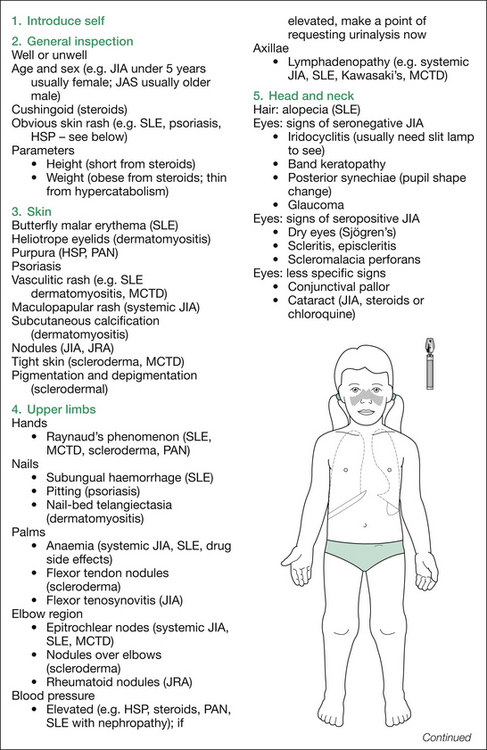

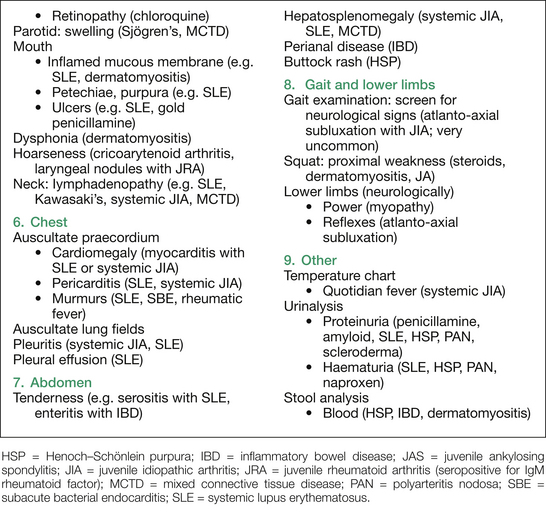

Figure 16.2 outlines the findings sought on inspection, plus those sought on assessing for extra-articular manifestations and drug side effects. A suggested order for this is: skin, hands, blood pressure, hair, eyes, mouth, neck, chest, abdomen and lower limbs neurologically, plus temperature chart, urine and stool analysis.

Examination

The following is the sequence suggested for whichever joints are being examined. Inspect the distribution of joint involvement (symmetry), note swelling, loss of normal contours, angulation, deformity, redness and muscle wasting. Next, feel the joint and periarticular areas for tenderness, warmth, effusion, ‘boggy’ swelling (thickened synovium and fluid), enthesitis and contractures. The range of movement (ROM) is then examined, active movement first. Test passive movement, paying attention to presence of soft-tissue restriction; for example, tenosynovitis or joint loss of ROM. Remember to watch the child’s face to detect any discomfort. Any loss of ROM should be quantified by descriptive terms such as minimally, moderately or severely reduced (see the section on JIA). Finally, function (which correlates with strength) should be tested.

Specific joints

Note that the normal range of movement (ROM) at each joint is given in degrees, in parentheses.

Upper limbs

Hands and wrists

Look at the dorsum first: note any skin rash or muscle wasting. Methodically inspect the wrist, followed by the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, proximal and distal interphalangeal (PIP and DIP) joints, and the nails. Then have the child turn the hands over and look at the palmar aspect in the same systematic fashion. Look for palmar or periungal erythema or punctuate vasculitic rash of SLE. Check for Gottron’s papules over PIP and MCP joints. Next, palpate each joint for tenderness and effusion. Flex and extend the child’s fingers while palpating over the flexor tendon sheaths (for tenosynovitis). Check ROM (active, then passive). Normal ROM values (in degrees) are as follows:

Shoulders

1. ‘Put your hands above your head’ (demonstrate to the child): tests flexion (90°) and abduction (180°).

2. ‘Give yourself a hug’ (demonstrate): tests adduction (45°).

3. ‘Scratch your back’ (demonstrate): tests external rotation (45°).

4. ‘Hide your hands behind your back’ (demonstrate): tests internal rotation (55°) and extension (45°).

Thoracolumbar spine

1. Flexion: should be able to touch toes. Best assessed by Schober’s method.

2. Extension: arching back (30° at lumbar area).

3. Lateral bending (50° to each side)/flexion. This has equal contributions from the thoracic and lumbar spine.

4. Lateral rotation: most easily checked with child sitting (40° to each side). This is almost entirely thoracic.

Lower limbs

Hips

(Both of these are tested with hips at 90° flexion.)

Note that the pelvis should be stabilised (by one hand fixing the ASIS) when checking all these movements. Then, have the child turn over on to the abdomen and test extension (30°). Gait examination serves as a functional assessment.

Ankles and feet

1. Ankle: plantar flexion (50°); extension (dorsiflexion) (10–20°).

2. Subtalar joint: inversion (35–40°); eversion (15–20°).

3. Midtarsal (talonavicular and calcaneocuboid) joints: abduction (10°); adduction (20°). The midtarsal joint is tested by stabilising the calcaneus with one hand and moving the forefoot with the other.

4. First metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint: plantar flexion (45°); extension (dorsiflexion) (70°). Note any crepitus or pain on moving the first metatarsal joint (may be selectively involved in spondyloarthropathies).