Chapter 42 Rheumatoid Arthritis

Conservative Surgical Procedures Open/Arthroscopic Synovectomy

Introduction

Involvement of the elbow is rarely the initial presenting sign of rheumatoid arthritis, nor does it usually present in isolation. The clinical signs in elbow pathology generally occur with more extensive disease, affecting up to 60% of the rheumatoid population.1 Patients often present late, and the options for treatment can be dramatically reduced due to age, disease progression and post-management rehabilitation requirements.

Background/aetiology

Recent advances in medical management (especially the anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α drugs including etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade) and adalimumab (Humira)) have significantly slowed the rate of disease progression and therefore dramatically reduced the number of patients presenting with severe rheumatoid joint deformity and destruction.2 Consequently early detection of the disease and medical intervention where appropriate have become a priority.

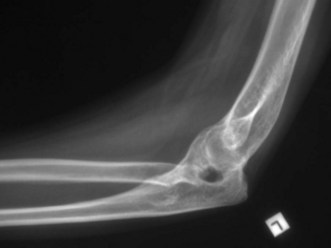

The presentation of rheumatoid arthritis is extremely variable, with systemic symptoms sometimes complicating the picture. When joint symptoms predominate it is often a symmetrical polyarthritis. Certainly, the hands and wrists are the most frequently affected joints, with the elbow being involved in 20–60% of cases.1 Despite this variable presentation, joint involvement in rheumatoid arthritis is always characterized by inflammation and synovial hypertrophy.3 Treatment should be tailored to the pathology as it progresses through the relatively predictable radiographic Larsen stages of disease4 (Fig. 42.1). Put simply, the inflammation and synovial thickening lead to effusion, cartilage breakdown, erosions, nodules and capsulo-ligamentous thinning.

Initially alternative causes of pain, effusion and swelling in the elbow must be excluded, such as septic arthritis, posttrauma, gout and even osteoarthritis. In the earlier stages of disease the diagnosis can be difficult, especially in rheumatoid monoarthritis or pauci-articular rheumatoid arthritis, and a synovial biopsy may be desirable. Arthroscopy facilitates diagnostic biopsy, with less morbidity in experienced hands than an open procedure.5

Intraoperative findings reveal thick, villous synovium with or without rice bodies. The exudate covers the native articular cartilage from the margins, destroying the smooth edges of the cartilage and reducing the joint space.6 The often purulent joint effusion leads to friable articular cartilage in the centre of the joint, and as the elbow has a high level of constraint, this often leads to flaps of cartilage catching and/or locking the elbow as it extends. This, in addition to loose body formation, results in the common presentation of extension loss with anterior capsular tightness.

Classifications based on clinical presentation (Mayo Clinic Performance Index) and/or radiographic appearance (Mayo Clinic radiographic classification, Larsen Dale and Eek classification5) (Table 42.1) have been published by Morrey and Adams7 (as well as the elbow functional assessment (EFA) scale8 and others), but no single classification covers the variety of clinical problems produced by rheumatoid disease in the elbow.

Table 42.1 Mayo Clinic classification of the rheumatoid elbow

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| I | No radiographic abnormalities except periarticular osteopenia with accompanying soft tissue swelling. Mild to moderate synovitis is generally present |

| II | Mild to moderate joint space reduction with minimal or no architectural distortion. Recalcitrant synovitis that cannot be managed with non-steroidal antiinflammatory medications alone |

| III | Variable reduction in joint space with or without cyst formation. Architectural alteration, such as thinning of the olecranon, or resorption of the trochlea or capitellum. Synovitis is variable and may be quiescent |

| IV | Extensive articular damage with loss of subchondral bone and subluxation or ankylosis of the joint. Synovitis may be minimal |

From Kauffman JI, Chen AL, Stuchin S, et al. Surgical management of the rheumatoid elbow. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2003;11:100–108; data originally from Morrey BF, Adams RA. Semiconstrained arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1992;74:479–490.

Presentation

Articular pain, valgus deformity

The classic presentation of the severe chronic rheumatoid patient is with pain and stiffness. Pain occurs from the usual joint receptors, but also secondary to the invasive nature of the disease as there can be gross destruction of joint surfaces and of ligamentous attachments producing articular incongruity and deformity. Patients commonly present with valgus laxity due to disruption of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) as well as radial head destruction.9 Over time valgus deformity can also lead to a tardy ulnar nerve palsy.

Non-articular lesions

The proliferative synovitis may lead to synovial cyst formation. Occasionally this may also occur at the proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ), which can result in an exertion of pressure on the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN).10 The ulnar nerve is at risk both from synovial proliferation due to its position within the cubital tunnel, and from a tardy ulnar nerve palsy from progressive valgus deformity.

Investigation

Imaging

The most reliable radiological classification for rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow is the Larson classification (Fig. 42.1). Recent advances in computed tomography (CT) have led to excellent quality three-dimensional (3D) images of the elbow to localize sites of impingement, and also to examine congruity of the joint. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is, however, the investigation of choice for assessing synovitis. The presence of fluid can be distinguished from boggy synovitis, and the sites of maximum involvement can help preoperative planning and decision making.11 Ultrasound is of value when observing early synovitis and cysts, and is particularly useful when plotting the course of the radial nerve prior to surgery.12

Treatment options

Aims of these options

Surgical treatment of the elbow is used for several clinical purposes:

| Arthroscopic procedures | Arthroscopic synovial biopsy |

| Arthroscopic synovectomy | |

| Arthroscopic capsular release | |

| Arthroscopic radial head resection | |

| Open procedures | |

| Lateral or Kocher approach | Synovectomy |

| Synovectomy and capsulectomy | |

| Synovectomy/capsulectomy and radial head excision | |

| Posterior interosseous nerve release and excision of bursa | |

| Posterior approach | Olecranon nodule |

| Olecranon bursa ± spur | |

| ‘OK’ procedure | |

| Medial approach | Ulnar nerve release/transposition |

| Medial capsular release | |

| Universal incision (posterior) | |

| All of the above | Total elbow arthroplasty |

Surgical techniques of typical conservative surgical procedures

Elbow arthroscopy

Technique

If a capsulectomy is required then the safest technique is to release it off the humerus superiorly. Capsulectomy on the medial side of the joint is achieved by shaving to the layer of brachialis, which protects the median nerve. A retractor facilitates this by elevating the ‘at-risk’ structures during shaving.13 Laterally, the radial nerve can lie on the capsule and be in immediate danger when an anterior release is being undertaken; again use of a retractor may be helpful.

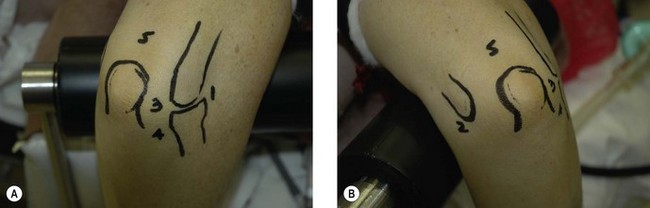

Clinical Pearl 42.2 The ‘LOST CORNER’ of the elbow; posterolateral gutter

Whilst arthroscopic radial head resection has been described,14 there is a potential for damage to the posterior interosseous nerve which lies directly anterior to the resection site. Indeed it has been recommend that this procedure is only for the expert arthroscopist (Figs 42.2–42.4).

Rehabilitation

Elbow arthroscopy usually produces significant swelling around the elbow by the end of the procedure. Regaining full range of movement (or as near as possible) is the main aim of rehabilitation in the immediate postoperative period. This can be achieved by the use of passive motion machines, long-acting brachial plexus blocks, and/or intra-articular infusion of local anaesthesia. More recently, however, concerns have been raised about the chondrotoxicity of some local anaesthetics.15 There is no doubt, however, that early mobilization, particularly in the postoperative period will reduce the risk of subsequent scarring. Obviously any technique to minimize scar response or heterotopic ossification is worthwhile.16

Outcome and literature review

Arthroscopic synovectomy has been shown to produce good results in a select population, although these are tempered by longer-term studies showing a deterioration in this initial improvement. When comparing this method to open synovectomy (23 and 23 patients respectively), Tanaka et al17 did not find a significant difference in clinical outcome after an average follow-up of 13 years. However, if the preoperative arc of flexion was less than 90°, then the patients who had undergone arthroscopic synovectomy had significantly better function. Finally, results also demonstrated an improvement in pain and function, with scores at mid- and long-term (13 years) follow-up, showing less deterioration over time with open synovectomy, although this was not statistically significant.

Jerosch et al18 and Nemoto et al19 both reported significantly improved pain and function scores with arthroscopic synovectomy in 103 and 11 patients at an average of 6.2 and 3 years, respectively. Jerosch also found that patients with a shorter duration of preoperative symptoms tended to have a better outcome. Horiuchi et al20 goes further to show that of 29 patients followed for 37 months, the Mayo Elbow Function Score (MEFS) and pain scores improved to a satisfactory level in patients with Larsen stage 1 or 2, compared with fair and poor results in Larsen stage 3 and 4. Lee and Morrey in 199721 described 93% ‘excellent and good’ early results in 11 patients (14 elbows) treated by arthroscopic synovectomy, although this deteriorated to 57% at final 42 month follow-up with 4/14 conversions to total elbow arthroplasty. This finding is consistent with other studies showing a more rapid deterioration of symptoms following the arthroscopic technique as compared to open.

Irradiation therapy (radiosynoviorthesis) has had some reported success in the management of early rheumatoid at the elbow.22 Combining arthroscopic synovectomy with irradiation has also been successfully used to manage early rheumatoid arthritis of the knee, although this has yet to be reported in the elbow.23 The results of arthroscopic resection of the radial head has been reported by Menth-Chiari et al14 in a cohort of 12 patients. They demonstrated an improved range of motion, diminished pain and improved function at a mean follow-up of 39 months. No patient was found to have instability.

Complications of treatment

General elbow arthroscopy complications

Nerve injury

All the nerves around the elbow are at risk during routine arthroscopy.21 The ulnar nerve can be damaged by a poorly positioned medial portal, or an anterior portal if the ulnar nerve is subluxed. If an anterior capsulectomy is performed, both the median and, particularly, the radial nerve can be damaged.

Specific complications from arthroscopic rheumatoid synovectomy

There are several reported cases of heterotopic ossification following arthroscopic debridement of the elbow. Ultimately, these will require an open operation to restore motion. Generally, however, the long-term outcome is good.14 We have seen one case only of joint ankylosis following arthroscopic debridement (Fig. 42.5), which was in a young girl. There are no reports in the literature of this complication. Radial and ulnar nerve palsies usually resolve spontaneously, as discussed earlier.

Open radial head excision and synovectomy (RHES) (± capsulectomy)

Technique

The procedure is usually undertaken under general anaesthesia, with the patient in a supine position. A high arm tourniquet is applied. Following preparation and draping the elbow is inspected for surface landmarks. An olecranon osteotomy may be necessary to achieve adequate exposure, although there is an added risk of non-union, loss of fixation and, ultimately, prominence of metalwork requiring removal. My preferred approach is via a Kocher incision if there is no requirement for capsular release. The alternative method is to perform a curved incision around the lateral epicondyle, following the humeral epicondylar ridge above the elbow and the common extensor origin below. This, like the lateral column procedure as published by Morrey et al,24 allows access to the anterior compartment if necessary (Fig. 42.6). (Please see complete step by step images of this procedure on text website.)

Outcome

The most reliably improved outcome measure is for pain relief. Brumfield and Resnick25 reported on 42 elbows in 35 patients all with improved rest pain after open synovectomy and RHES at a minimum of 2 years follow-up, most of which had no further significant deterioration after an average of 7 years. Eichenblat et al26 similarly showed improvement in rest pain in all but three of their 25 elbows in 21 patients at a follow-up of 2–11 years. Similarly Marmor27 showed 17 of 19 patients had improvement at an average of 3.5 years. Lonner and Stuchin28 retrospectively showed improvement in function and pain in all 11 patients (12 elbows) at an average of 6.1 years follow-up after open synovectomy, RHES and anterior capsule release. They also found no significant radiographic disease progression at final follow-up. Inglis et al29 studied 28 elbows in 26 patients with improved pain despite three patients experiencing spontaneous ankylosis after a minimum of 1-year follow-up (average 3.5 years). Finally, Torgerson and Leach30 reported five patients all of whom showed improvement at an average follow-up of 2 years. In all these studies the patients had advanced disease (stages III and IV) according the American Rheumatism Association criteria. In contrast, improvements regarding the arc of motion in flexion/extension are variable with at best 50% of patients showing improvement in the short term. The remaining patients reported no change, and up to 20% showed some loss of motion. Functional elbow outcome scores, however, have shown more durable improvements mainly as a result of pain relief, but as with motion, pain relief can deteriorate over time. Morrey in a review of the literature concludes that approximately 90% of patients experience relief from pain at 3 years, 75–80% at 5 years and 67% at 10 years.24

Maenpaa et al31 showed approximately 77% survivorship (no reoperation) at 5 years following 103 open synovectomies. Of the remaining 23%, eight re-synovectomies and 14 total elbow replacements were performed. Not surprisingly, none of the patients with a low Larsen stage (0–2) required conversion to total elbow replacement at final follow-up, and patients with a shorter duration of preoperative symptoms tended to have a better outcome. Comparisons of RHES conversion to total elbow replacement and primary total elbow replacement suggests that prior surgery makes arthroplasty surgery technically more difficult and increases the risk of complications (Schemitsch et al,32 Whaley et al33 and Woods et al34).

Complications

Whilst strictly not a complication, one of the problems of radial head resection and synovectomy (RHES) is that it does not alter the progression of disease. Specifically as the procedure does not address ulnohumeral cartilage damage, and if this progresses the patient will require further surgical intervention. Spontaneous ankylosis, decreased range of motion, nerve palsies (mainly radial and ulnar), instability and infection can all occur.25–27,29,30 Ankylosis is more common in seronegative arthropathies such as dermatomyositis and ankylosing spondylitis29 and usually occurs in the advanced stages of disease. Nerve palsies usually spontaneously resolve within 6 months. There can also be increased valgus instability after radial head resection, although this can be minimized by preserving the lateral collateral ligament complex and replacing the head if necessary. This occurs less often than one may expect due to the presence of concomitant disease at the distal radioulnar joint, which allows for compensatory motion. Finally, infection is a potential risk in many of these patients due to their often immunocompromised state. However, this can be avoided if close attention is given to haemostasis, wound closure and drain placement.

Summary Box 42.3 Comparison of relative indications of radial head excision/synovectomy and total elbow replacement

| Radial head excision/synovectomy | Total elbow replacement |

|---|---|

| Younger | Older |

| Manual worker | Non-manual function |

| Reasonable bone stock | Poor bone stock |

| History of sepsis | No history of sepsis |

| Variable compliance | Good compliance |

Figures 42.WS4–WS26 Open radial head resection and capsulectomy in pictures.

1 Lehtinen JT, Kaarela K, Ikavalko M, et al. Incidence of elbow involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. A 15 year endpoint study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):70-74.

2 Caporali R, Pallavicini FB, Filippini M, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with anti-TNF-alpha agents: a reappraisal. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8(3):274-280.

3 Lehtinen JT, Kaarela K, Kauppi MJ, et al. Bone destruction patterns of the rhuematoid elbow: a radiographic assessment of 148 elbows at 15 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(3):253-258.

4 Larsen D, Dale K, Eke M. Radiographic evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis and related conditions by standard reference films. Acta Radiol (Diagn). 1977;18:481-491.

5 O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1992;74(1):84-94.

6 Kauffman JI, Chen AL, Stuchin S, et al. Surgical management of the rheumatoid elbow. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:100-108.

7 Morrey BF, Adams RA. Semiconstrained arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1992;74(4):479-490.

8 de Boer YA, van den Ende CH, Eygendaal D, et al. Clinical reliability and validity of elbow functional assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(9):1909-1917.

9 Lehtinen JT, Kaarela K, Kauppi MJ, et al. Valgus deformity and proximal subluxation of the rheumatoid elbow: aradiographic 15 year follow up study of 148 elbows. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(8):765-769.

10 Ishikawa H, Hirohata K. Posterior interosseous nerve syndrome associated with rheuamtoid synovial cysts of the elbow joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:134-139.

11 Ostergaard M, Szkudlarek M. Imaging in rheumatoid arthritis-why MRI and ultrasonography can no longer be ignored. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32(2):63-73.

12 Lerch K, Borisch N, Paetzel C, et al. Sonographic evaluation of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis: a classification of joint destruction. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29(8):1131-1135.

13 Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2001;83(1):25-34.

14 Menth-Chiari WA, Ruch DS, Poehling GG. Arthroscopic excision of the radial head: clinical outcome in 12 patients with post-traumatic arthritis after fracture of the radial head or rheumatoid arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(9):918-923.

15 Chu CR, Izzo NJ, Coyle CH, et al. The in vitro effects of bupivacaine on articular chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2008;90:814-820.

16 Gofton WT, King GJW. Heterotopic ossification following elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(1):E2.

17 Tanaka N, Sakahashi H, Hirose K, et al. Arthroscopc and open synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2006;88(3):521-525.

18 Jerosch J, Schroder M, Schneider T. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2005;87:2114-2121.

19 Nemoto K, Arino H, Yoshihara Y, et al. Arthroscopic synovectomy for the rheumatoid elbow: a short-term outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;13(6):652-655.

20 Horiuchi K, Momohara S, Tomatsu T, et al. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2002;84(3):342-347.

21 Lee BPH, Morrey BF. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the elbow for rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1997;79(5):770-772.

22 Klett R, Lange U, Haas H, et al. Radiosynoviorthesis of medium-sized joints with rhenium-186-sulphide colloid: a review of the literature. Rheumatology. 2007;46(10):1531-1537.

23 Klug S, Wittmann G, Weseloh G. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the knee joint in early cases of rheumatoid arthritis: follow-up results of a multicenter study. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(3):262-267.

24 Mansat P, Morrey BF. The column procedure: a limited lateral approach for extrinsic contracture of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1998;80:1603-1615.

25 Brumfield RH, Resnick CT. Synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1985;67:16-20.

26 Eichenblat M, Hass A, Kessler I. Synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1982;64:1074-1078.

27 Marmor L. Surgery of the rheumatoid elbow – follow-up study on synovectomy combined with radial head excision. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1972;54:573-578.

28 Lonner JH, Stuchin SA. Synovectomy, radial head excision, and anterior capsular release in stage III inflammatory arthritis of the elbow. J Hand Surg (Am). 1997;22(2):279-285.

29 Inglis AE, Ranawat CS, Straub LR. Synovectomy and debridement of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1971;53:652-662.

30 Torgerson WR, Leach RE. Synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis: report of five cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1970;52:371-375.

31 Maenpaa H, Kuusela P, Lehtinen J, et al. Elbow synovectomy on patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;412:65-70.

32 Schemitsch EH, Ewald FC, Thornhill TS. Results of total elbow arthroplasty after excision of the radial head and synovectomy in patients who had rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1996;78(10):1541-1547.

33 Whaley A, Morrey BF, Adams R. Total elbow arthroplasty after previous resection of the radial head and synovectomy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2005;87(1):47-53.

34 Woods DA, Williams JR, Gendi NS, et al. Surgery for rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow: a comparison of radial-head excision and synovectomy with total elbow replacement. J Should Elbow Surg. 1999;8(4):291-295.