53 Rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The cause of rheumatoid arthritis remains unclear with hormonal, genetic and environmental factors playing a key role. Genetic factors contribute 53–65% of the risk of developing this disease. The HLA-DR4 allele is associated with both the development and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Cigarette smoking is a strong risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis. A study of over 3000 women clearly linked the length of time that people had smoked with rheumatoid arthritis (Karlson et al., 1999). Patients with a smoking history of 25 years or more were increasingly likely to develop seropositive disease with nodules and erosions on radiology.

Clinical manifestations

There are different patterns of clinical presentation of rheumatoid arthritis. The disease may present as a polyarticular arthritis with a gradual onset, intermittent or migratory joint involvement, or a monoarticular onset. In addition, extra-articular manifestations may be present (Box 53.1). Extra-articular features occur in approximately 75% of seropositive patients and are often associated with a poor prognosis.

Box 53.1 Examples of the extra-articular features of rheumatoid arthritis

Nodules; may be subcutaneous or within the lungs, eyes or heart

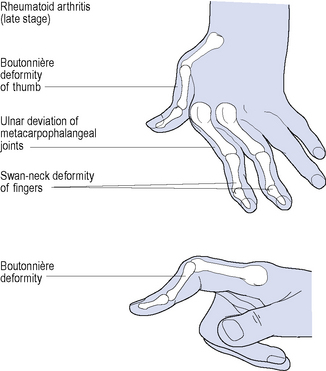

Disease onset is usually insidious with the predominant symptoms being pain, stiffness and swelling. Typically, the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the fingers, interphalangeal joints of the thumbs, the wrists, and metatarsophalangeal joints of the toes are affected during the early stages of the disease. Rheumatoid arthritis–associated deformities affecting multiple joints of the hands are shown in Fig. 53.1. Other joints of the upper and lower limbs, such as the elbows, shoulders and knees, are also affected. Morning stiffness may last for 30 min to several hours, and usually reflects the severity of joint inflammation. Up to one-third of patients also suffer from prominent myalgia, fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss and depression at disease onset.

Diagnosis

Emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is extremely important to prevent disease activity, duration and ultimately joint destruction. The American Rheumatism Association (ARA) criteria (Box 53.2) were principally designed for disease classification in patients with established disease and are not sensitive for patients in the early stages of rheumatoid arthritis (Arnett et al., 1988). The Disease Activity Score using 28 joint counts (DAS28) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response are some of the tools used by rheumatologists to assess disease activity and to monitor the patient’s response to treatment (see Boxes 53.3 and 53.4).

Box 53.2 American Rheumatism Association criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis

The presence of at least 4 of these indicates a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

Box 53.3 Summary of DAS28 criteria in the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis

DAS28 is a composite formula. Four parameters are used to calculate a disease severity score:

Programmed calculators are used to determine the final DAS28.

High disease activity: DAS28 of >5.1

Moderate disease activity: DAS28 of >3.2 to 5.1

Box 53.4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR 20) response assessment in rheumatoid arthritis

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Treatment

There are four primary goals in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis:

Drug treatment

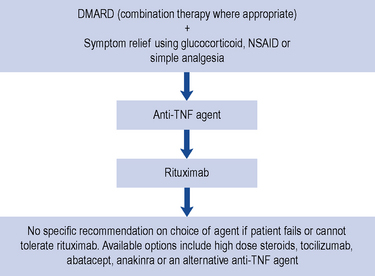

Guidance for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis has been issued and this is summarised in Fig. 53.2.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAIDs vary in their selectivity for the COX-1 and COX-2 isoforms, and are categorised as either non-selective NSAIDs or selective COX-2 inhibitors, otherwise known as the coxibs (Table 53.1). Non-selective NSAIDs generally block both COX-1 and COX-2, whereas the coxibs have higher selectivity for the COX-2 isoform. However, COX-2 selectivity in NSAIDs varies according to the dose of drug given, which is demonstrated by the dose-related toxicity exhibited by some agents such as ibuprofen. The three most commonly used non-selective NSAIDs have differing levels of COX-1 or COX-2 selectivity: diclofenac is COX-2 ‘preferential’, whereas ibuprofen and particularly naproxen preferentially inhibit COX-1. Originally, inhibition of COX-2 was thought to be involved solely with the anti-inflammatory, anti-pyretic and analgesic properties of NSAIDs. However, it is possible that COX-2 inhibition may also impair endothelial health, cause a prothrombotic state and promote cardiovascular disease.

| Non-selective NSAIDs | COX-2 inhibitors |

|---|---|

| Aceclofenac | Celecoxib |

| Acemetacin | Etoricoxib |

| Azapropazone | |

| Dexibuprofen | |

| Dexketoprofen | |

| Diclofenac | |

| Etodolac | |

| Fenbufen | |

| Fluribprofen | |

| Ibuprofen | |

| Indometacin | |

| Ketoprofen | |

| Meloxicam | |

| Nabumetone | |

| Naproxen | |

| Piroxicam | |

| Tenoxicam | |

| Tiaprofenic acid |

Safety

At present, the exact cardiovascular risk for individual selective COX-2 inhibitors and NSAIDs is not known. Evidence from clinical trials of COX-2 inhibitors suggests that about 3 additional thrombotic events per 1000 patients/year may occur in the general population (MHRA, 2006).

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

Joint damage is known to occur early in rheumatoid arthritis and is largely irreversible. The need for early intervention with DMARDs as part of an aggressive approach to minimise disease progression has become standard practice and is associated with better patient outcome. Early introduction of DMARDs also results in fewer adverse reactions and withdrawals from therapy (NCCCC, 2009).

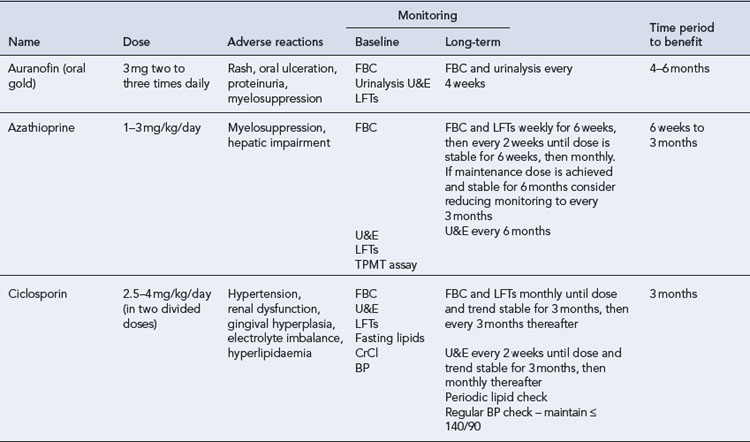

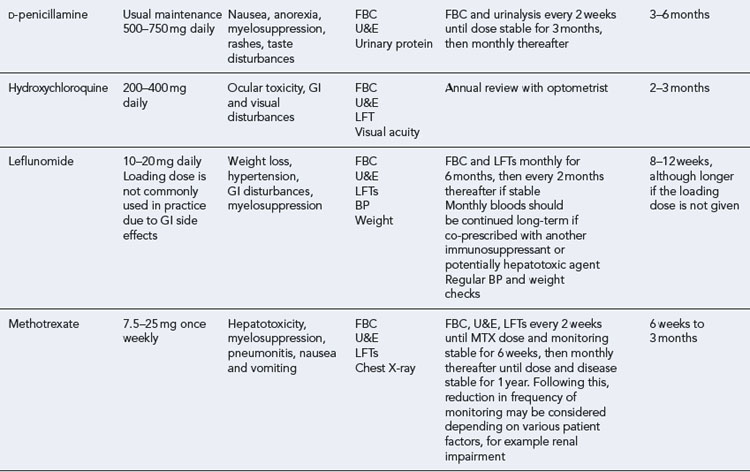

The DMARDs that are commonly used for rheumatoid arthritis and have clear evidence of benefit are methotrexate, sulphasalazine, leflunomide and intramuscular gold (O’Dell, 2004). There is less compelling evidence for the use of hydroxychloroquine, d-penicillamine, oral gold, ciclosporin and azathioprine, although these agents do improve symptoms and some objective measures of inflammation. The exact mechanism of action of these drugs is unknown. All DMARDs inhibit the release or reduce the activity of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, interleukin-1, interleukin-2 and interleukin-6. Activated T-lymphocytes have been implicated in the inflammatory process, and these are inhibited by methotrexate, leflunomide and ciclosporin.

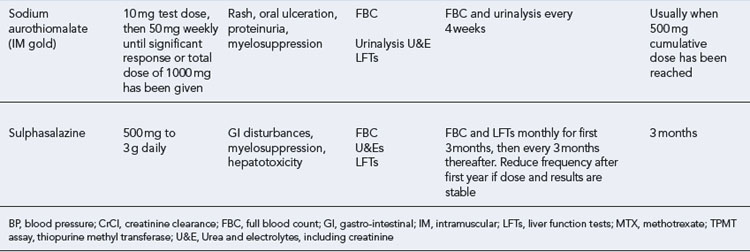

Patients should be made aware that the DMARDs all have a slow onset of action. They must be taken for at least 8 weeks before any clinical effect is apparent, and it may be months before an optimal response is achieved. Whilst early initiation of DMARDs is crucial, it is important to ensure the patient is maintained on therapy to maintain disease suppression. This itself is a challenge, due to the toxicity profiles of the majority of these drugs (see Table 53.2). The majority of the DMARDs require regular blood monitoring. Guidelines are available on the action to take in the event of abnormal blood results (Chakravarty et al., 2008).

Recommendations regarding the use of DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis are summarised in Box 53.5 (NCCCC, 2009). Patients with a new diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis should be offered combination DMARD therapy as first-line therapy as soon as possible, ideally within 3 months of the onset of persistent disease symptoms. The combination therapy should include methotrexate and at least one other DMARD, usually sulphasalazine and/or hydroxychloroquine. Evidence suggests that combination therapy appears to be superior in terms of benefits to symptoms, quality of life, remission rates and slowing of joint damage, when compared to monotherapy. Once sustained and satisfactory levels of disease control have been achieved, the doses of drugs should be cautiously reduced to levels that continue to maintain disease control.

Box 53.5 Key points regarding DMARD therapy (NCCCC, 2009)

Introduce DMARD therapy early (within 3 months ideally)

Use combination DMARDs involving methotrexate and at least one other DMARD

Withdraw cautiously when disease is stable to doses that maintain disease control

In patients where combination therapy is not appropriate, for example where there are contraindications to a drug due to existing co-morbidities, DMARD monotherapy should be started, placing greater emphasis on fast escalation to a clinically effective dose rather than on choice of agent (NCCCC, 2009).

Methotrexate

Following a number of patient incidents involving methotrexate toxicity, guidance on safe use was issued by the National Patient Safety Agency (Box 53.6). Methotrexate-monitoring booklets are routinely given to patients when therapy is initiated. The booklet contains information to reinforce counselling points such as warning symptoms and drug interactions, and has sections where prescribers can enter in dose details (in number and strength of tablets) and record blood results. Methotrexate tablets are available as 2.5-mg and 10-mg strengths; most pharmacies will dispense the 2.5-mg strength only for non-chemotherapy indications such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Box 53.6 Summary of recommendations for the safe prescription of methotrexate

All prescriptions must specify a dose

The term ‘as directed’ should be avoided on prescriptions

The strength of tablets supplied should remain consistent to avoid confusion regarding dose

Glucocorticoids

Steroids are also used as a bridging therapy and are particularly useful when introducing DMARDs which may take several months to take effect. There are various studies which demonstrate steroids are disease modifying in slowing radiological damage over 2 years. Doses of prednisolone 7.5 mg daily have been suggested to reduce the rate of joint destruction in moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis of less than 2 years’ duration (NCCCC, 2009).

Biological therapies

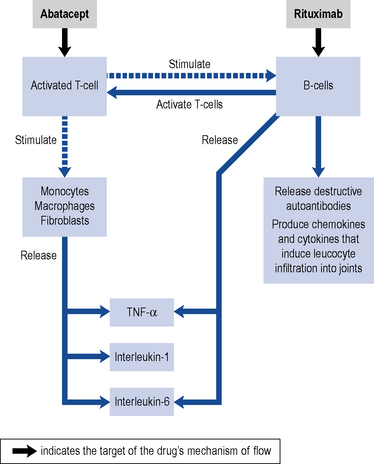

Over the past decade, there have been significant advances in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis due to emerging biological therapies. The so-called biologics in rheumatoid arthritis are genetically engineered monoclonal antibodies which selectively target different parts of the inflammatory pathways (Fig. 53.3). Activated T-cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. Adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab and certolizumab pegol target TNF-α, anakinra and tocilizumab target the interleukins, whilst abatacept and rituximab act on T-cells and B-cells, respectively.

Anti-TNF agents

Adalimumab is a recombinant human monoclonal antibody that binds to and neutralises TNF-α. Etanercept is a human TNF fusion protein that binds to TNF cell surface receptors, thereby inhibiting interaction of TNF-α with its receptors. Certolizumab pegol is a pegylated antibody fragment which binds and neutralises TNF-α and is thought to have a relatively more rapid onset of action. Golimumab is the most recent addition to this family of agents and has the advantage of having a less frequent dosing schedule. (Table 53.3). Optimum clinical benefit is achieved when these drugs are used in combination with methotrexate. However, adalimumab, etanercept and certolizumab pegol can be used alone as monotherapy in patients for whom methotrexate is not appropriate or not tolerated.

Table 53.3 Biologic agents used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and typical dose regimens in adults

| Drug | Usual dose | Route |

|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab | 40 mg every 2 weeks | Subcutaneous |

| Certolizumab pegol | 400 mg at week 0, 2 and 4, then 200 mg every 2 weeks thereafter | Subcutaneous |

| Etanercept | 25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg weekly | Subcutaneous |

| Golimumab | 50 mg monthly | Subcutaneous |

| Infliximab | 3 mg/kg at week 0, 2 and 6, then every 8 weeks thereafter | Intravenous infusion |

| Rituximab | 1 g then 1 g 2 weeks later Max 2 courses/year |

Intravenous infusion |

| Abatacept | 750 mg at week 0, 2 and 4, then every 4 weeks thereaftera | Intravenous infusion |

| Anakinra | 100 mg daily | Subcutaneous |

| Tocilizumab | 8 mg/kg every 4 weeks | Intravenous infusion |

a For a patient weighing between 60 and 100 kg; dose modifications are necessary for patients outside this weight range.

Place in therapy

Guidance on the use of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab (NICE, 2007) and certolizumab pegol (NICE, 2010a) have been published, with the appraisal of golimumab pending. Adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept or infliximab are recommended as treatment options in adults who meet the following criteria:

Changes in eligibility criteria have been suggested (Deighton et al., 2010) which recommend patients should have tried two DMARDs, but those with DAS28 > 3.2 and at least three or more tender joints and three or more swollen joints should be eligible for an anti-TNF agent. Whether NICE will adapt their guidance accordingly is unclear.

Use of the anti-TNF agents above their starting doses as listed in Table 53.3 is not advocated. According to their product licences, doses of adalimumab and infliximab may be escalated according to response, but this does not generally occur in practice.

Rituximab

Rituximab is a chimeric human-murine monoclonal antibody which binds to the C20 antigen on B-lymphocytes to mediate B-cell lysis. It causes depletion of peripheral B-cells which play a role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Recovery of B-cells appears to occur 6 months after treatment, with some patients showing prolonged B-cell depletion persisting up to 2 years after treatment (Emery et al., 2004).

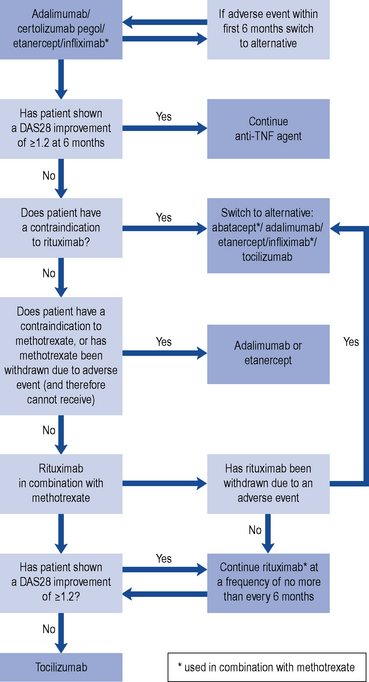

In practice, rituximab is used in line with its product license, i.e. after failure of, or intolerance to, DMARD therapy including at least one anti-TNF agent. Patients may continue on rituximab therapy with infusions no more frequent than every 6 months, provided they demonstrate an adequate response of a DAS28 improvement of 1.2 points or more (NICE, 2010b).

Abatacept

Abatacept acts by blocking the full activation of T-cells thereby inhibiting the release of inflammatory cytokines. It is licensed for use in combination with methotrexate in the treatment of moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis in adults who have had an insufficient response or intolerance to other DMARDs including at least one anti-TNF agent and who cannot receive rituximab because they have a contraindication to rituximab, or when rituximab is withdrawn due to an adverse event (NICE, 2010a).

Anakinra

Anakinra blocks the binding of interleukin-1 to its receptor, thus inhibiting the inflammatory effects of interleukin-1. The evidence of its benefit in rheumatoid arthritis is weak and it is considered modestly effective. There are no trials directly comparing anakinra with other biologic agents; adjusted indirect comparisons suggest that anakinra may be significantly less effective at relieving the clinical signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis than anti-TNF agents in combination with methotrexate. Anakinra is not cost effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and availability for routine use in the NHS has not been supported (NCCCC, 2009).

Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab is recommended for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients who fulfil the following criteria (NICE, 2010c):

Which biologic?

At present, anti-TNF agents remain the first-line biological therapy. Following failure or intolerance to one anti-TNF agent, patients should then be treated with rituximab. However, if patients cannot receive rituximab due to a contraindication, adverse effect, or intolerance to methotrexate, there remains a number of treatment options (see Fig. 53.4).

Patient care

Patient education and counselling are vital aspects in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Patients should be encouraged to engage actively in their pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment, and take responsibility for ensuring their medication regimen is safe and effective. Medicine information sheets are available from the Arthritis Research UK with further information available on their website (http://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/). Monitoring of the potentially toxic DMARDs is essential as non-adherence with the monitoring schedule may have serious consequences. Patients should be reminded of the warning symptoms that must trigger them to contact a healthcare professional. They should also be counselled to inform healthcare professionals of all the medication they are taking before starting a new medicine, and this includes use of over-the-counter products such as ibuprofen or aspirin.

Some of the common therapeutic problems that are encountered in the management of rheumatoid arthritis are outlined in Table 53.4.

Table 53.4 Examples of therapeutic problems encountered in the management of rheumatoid arthritis

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| NSAID not providing adequate symptom control | Consider alternative NSAID |

| Review DMARD dose | |

| If patient has been on DMARD for a sufficient time period but with no improvement, consider alternative disease-modifying agent, i.e. another DMARD or a biologic agent | |

| Consider short-term systemic steroids for rapid relief of symptoms | |

| Patient non-adherent with DMARD monitoring regimen | Education and counselling |

| If patient still unwilling to comply, the safest option would be to consider swapping to DMARDs that require less stringent blood monitoring, for example hydroxychloroquine or sulphasalazine | |

| However, relative drug efficacy must also be considered | |

| Nausea and vomiting with methotrexate | Ensure patient is taking folic acid |

| Add anti-emetic therapy | |

| Change to parenteral methotrexate | |

| Disease flares when trying to withdraw systemic steroids | Use a slower withdrawal regimen, for example decrease by 1 mg each month |

| If patient cannot be withdrawn completely from steroids, consider reducing to lowest dose possible as maintenance treatment | |

| Side effects of long-term steroids | Aim to use steroids for short-term treatment only |

| Ensure concomitant treatment of PPI, bisphosphonate and calcium and vitamin D preparations are prescribed where appropriate | |

| Patient cannot tolerate stinging at injection site associated with adalimumab or etanercept administration | Consider switching to infliximab |

Osteoarthritis

Guidelines are available for the management of osteoarthritis (NCCCC, 2008). If the three core interventions are not sufficient, paracetamol and topical NSAIDs can be added in to the treatment regimen. Paracetamol and topical NSAIDs are deemed ‘relatively safe pharmaceutical options’ compared to other available agents such as oral NSAIDs, opioids and intra-articular steroids. Other interventions which may also be considered include joint arthroplasty, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), supports and braces, or manual therapy involving manipulation and stretching.

Answers

Questions

Answers

Arnett F.C., Edworthy S.M., Bloch D.A., et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum.. 1988;31:315-324.

Chakravarty K., McDonald H., Pullar T., et alon behalf of the British Society for Rheumatology, British Health Professionals in Rheumatology Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group in consultation with the British Association of Dermatologists. BSR/BHPR guideline for disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy in consultation with the British Association of Dermatologists. Rheumatology. 2008. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel216b. Available at http://www.rheumatology.org.uk/includes/documents/cm_docs/2009/d/diseasemodifying_antirheumatic_drug_dmard_therapy.pdf

Deighton C., Hyrich K., Ding T., et alon behalf of BSR Clinical Affairs Committee & Standards, Audit and Guidelines Working Group and the BHPR. BSR and BHPR rheumatoid arthritis guidelines on eligibility criteria for the first biological therapy. Rheumatology. 2010. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq006b

Emery P., Sheeran T., Lehane P.B., et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab at 2 years following a single treatment in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum.. 2004;50(Suppl. 9):S659.

Karlson E.W., Lew J.M., Cook N.R., et al. A retrospective cohort study of cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in female health professionals. Arthritis Rheum.. 1999;42:910.

Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors. Current Problems in Pharmacovigilance. 2006;31:7.

National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Osteoarthritis: National Clinical Guideline for Care and Management in Adults. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. Available at http://www.gserve.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG59NICEguideline.pdf

National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Rheumatoid Arthritis: National Clinical Guideline for the Management and Treatment in Adults. London: NICE; 2009. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG79NICEGuideline.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Adalimumab, Etanercept and Infliximab for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. In: Technology Appraisal 130. London: NICE; 2007. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA130guidance.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Certolizumab Pegol for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. In: Technology Appraisal 186. London: NICE; 2010. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12808/47544/47544.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, Rituximab and Abatacept for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis After the Failure of a TNF Inhibitor. In: Technology Appraisal 195. London: NICE; 2010. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13108/50413/50413.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Tocilizumab for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. In: Technology Appraisal 198. London: NICE; 2010. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13100/50391/50391.pdf

O’Dell J.R. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2004;350:2591-2602.

Firestein G., Panayi G.S., Wollheim F.A., editors. Rheumatoid Arthritis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Hochberg M.C., Silman A.J., Smolen J.S., et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis. London: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2008.

Sharma L., Berenbaum F., editors. Osteoarthritis. London: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2007.

Taylor P.C. Rheumatoid Arthritis in Practice. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd; 2007.