CHAPTER 74 Rheumatoid Arthritis

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that has been known to exist since at least the 1800s,75,109 when the first detailed description was reported. Indirect evidence that it may have existed as far back as 4000 to 5000 years ago has been reported.100,102,103 Despite extensive research into its etiology and many theories about its pathogenesis, no uniform idea explains its many presentations and clinical course.17,64 In this chapter, the issue is discussed in general terms. The surgical management of the elbow is discussed in Chapters 54 and 55.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

This disease occurs worldwide and has a prevalence of about 0.5% to 2%.112 There is a female preponderance of 2 to 4 in most studies. The etiology of this disease is unknown. The presence of HLA-DR4, the gene for the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), in an increased frequency in patients with RA was a landmark observation,120 and several studies reconfirmed this and showed an increased risk of developing RA in individuals positive for the MHC class II DR-4 gene. Several studies show a strong correlation with the presence of HLA-Dw4 and Dw14 (HLA alleles DRB1*0401 and HLA-DRB1*0404).81,87 This, however, explains only a part of the genetic risk.2,52 The fact that only 1 : 20 to 1 : 35 individuals in the general white population who inherit these genes are at risk for developing RA suggests that other genetic and nongenetic factors3,86,110,133 are involved. Several investigators are currently trying to perform microsatellite mapping to identify other genes that may influence the disease. This approach has led to several likely candidates in animal studies using the rat collagen–induced model of RA.48,95 It would be of interest to see whether these can be confirmed in human studies also. Nongenetic factors that have been suggested include infections,28 pregnancy,111 and smoking,113 and others. These factors continue to be investigated.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The etiology of RA is unknown. The genetic predisposition, the involvement of activated immune cells, the clonal expansion of the cells in the pathologic lesions, and the response to immunosuppressive therapy suggest that this disease is immune mediated. The observation that MHC gene HLA-DR4 was associated with RA120 directly linked the antigen-presenting cells with the immune response and suggested that antigen-induced activation was central to the pathogenesis of this disease.134 Soon, however, it was observed that other HLA-DR antigens (HLA-DR9, HLA-DR3, and HLA-Dw16) were similarly associated in different populations.66,106,138 Some of the initial differences were explained by Gregersen and colleagues’ proposal of the shared epitope hypothesis,46,87 which suggested the significance of the shared sequence in the third hypervariable region. Further studies have led to the observation that multiple genes contribute to the genetic component of susceptibility.121,135 Synovial membrane biopsies of recent-onset disease reveal inflammatory cells, including macrophages, T cells, B cells, occasionally plasma cells, and fair number of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, along with edema and increased vascular permeability. As the disease progresses, the inflammatory process intensifies, with macrophages and lymphocytes either developing into nodular aggregates or as diffuse infiltrates. Increased angiogenesis is evident. This inflammatory process progresses and starts to invade normal tissue, leading to erosions, joint space narrowing, and ultimately, destruction of the joint.

Interest in recognizing the putative antigen is high, and several candidate antigens have been and are being investigated. These include type II collagen,79 proteoglycans,60 cartilage link protein,92 Epstein-Barr virus,6 65-kDa heat shock protein,141 and Proteus mirabilis.31 Some evidence exists for each of them, and yet no one antigen explains the whole picture. This suggests that several different antigens can trigger the disease, with cross-reactivity to a self-antigen leading to a self-perpetuating autoimmune process. Local production and release of cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-8, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and increased expression of intercellular adhesion molecular (ICAM) and lymphocyte function-associated molecules (LFA) and others, contribute to the enhancement of the inflammatory process.119 Of the various cytokines released, TNF-α, a proinflammatory cytokine, is thought to play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of this disease and this has led to development of various new therapeutic agents that are capable of blocking TNF (see below under treatment). B cells are activated and may be involved in antigen presentation.45 They also help plasma cells to produce increased amounts of immunoglobulins, particularly rheumatoid factors (RF). These form immune complexes, which are capable of activating the complement system, leading to enhanced local inflammation. Local release of enzymes capable of damaging the joint (e.g., stromelysin, gelatinase, collagenase) has been demonstrated. These contribute to the ongoing damage.49,143

CLINICAL FEATURES

The presentation of RA can be variable. Obviously, when patients present with a symmetric polyarthritis, the diagnosis of RA is very high on the list of possibilities. On the other hand, when patients present with systemic symptoms, the diagnosis is more uncertain. Subacute bacterial endocarditis, a paraneoplastic syndrome, malignancy,33 hepatitis C,99 or other connective tissue disease should be kept in mind. Patients have been known to present with fever of unknown origin and a clinical picture of Still’s disease, prominent fibrositis that can be mistaken for polymyalgia rheumatica, and episodic oligoarthritis (palindromic rheumatism). All of these conditions can be presenting features of RA (Box 74-1). Even when the joint symptoms are dominant, the pattern of presentation can be variable. Patients can present with a single joint swelling (21%), few swollen joints (44%), or a more typical polyarthritis (35%). The onset may be acute (days or weeks) in about half of the patients, whereas an insidious presentation is seen in the other half. About 32% of the patients present with disease of the small joint, whereas 16% present with medium-sized joints involved. Twenty-nine percent have large joints involved at onset, and 26% have a combination.36 Although the American College of Rheumatology revised the criteria for RA (Box 74-2), it is important to remember that these are for classification of groups of patients who are entered into studies and should not be used as diagnostic criteria in individual patients.8

BOX 74-2 American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Rheumatoid Arthritis

The joint reacts to an insult in a limited number of ways. It is stiff, painful, tender, and swells. Loss of function may result. If the process continues, the joint sustains damage, which may lead to deformity andpermanent compromise in function. Inflammation affects all the joints in the same way, and one can observe these changes in various diarthroidal joints in the patient with RA. Stiffness that improves with use lasting more than 30 minutes is considered significant. It is thought to be due to swelling of the joint and periarticular tissues, leading to redistribution of interstitial fluid when the joint is in one position for several hours (e.g., overnight). Some of these patients also experience a generalized stiffness involving the trunk, shoulder girdles, and hip girdles. This also improves with physical activity21 but recurs with rest and inactivity. The mechanism of this systemic stiffness is not clear but correlates with the activity of disease and can be used as a measure of response to treatment.

Pain experienced by the patients is due to the ongoing inflammation. This leads to local (intra-articular) fluid accumulation and swelling of the synovial lining. Typically, the swelling observed is symmetric in a joint in contrast to the swelling seen in degenerative osteoarthritis, which is asymmetric. The cause of predominant bilateral symmetry is not known, but local innervation and release of inflammatory neuropeptides have been suggested as factors.61,90,105 The presence of synovial swelling and synovial fluid is characteristic evidence of inflammation in the joint, as pain and decreased function can be present owing to extra-articular disease. Motion must contribute to the damage, since joints spared from this are spared by the disease.14,44,124 The diarthrodial joints of the thoracic and lumber spine are very rarely involved, and motion may play a role in this also.96,115

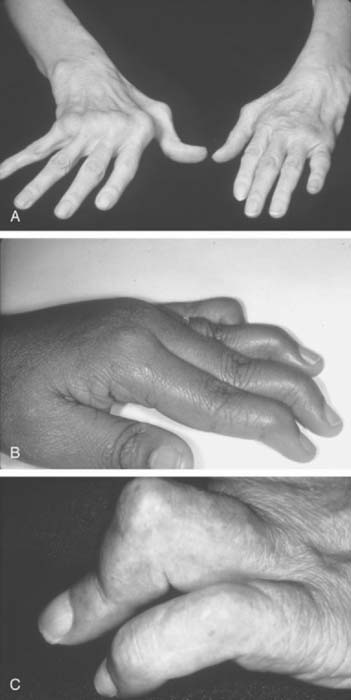

The inflammation in RA goes through intermittent exacerbations and remissions. This cycle leads to stretching and damage of the joint capsule and ligaments. Disuse and inflammation lead to weakness of the supporting muscles.108,123 These factors, and recurring mechanical forces that change as the stability of the supporting tissues is compromised, lead to development of deformities that gradually increase with time (Figs. 74-1 and 74-2).

The hands and wrist are the most common joints involved in this disease and cause the most disability. Elbow involvement has been reported in 20% to 65% of patients with RA. The earliest change noted in the elbow is loss of extension. In most cases, this occurs imperceptibly, because the patient has involvement of the hands and wrist at the same time, and these deformities are usually more disabling. Loss of the groove on either side of the olecranon is usually good evidence of elbow involvement.91 Disease progression is similar to that with other joints; occasionally, large cystic swellings can occur (Fig. 74-3).

EXTRA-ARTICULAR MANIFESTATIONS

Rheumatoid Nodules

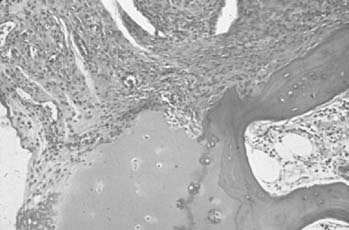

Nodules occur in about 20% of patients with progressive seropositive disease. These nodules are most commonly subcutaneous and occur along the extensor surfaces of the arms, elbows, olecranon bursae, spine, occiput (Fig. 74-4), and other areas exposed to mechanical pressure. They can be very small, for example, ranging from less than 1.00 mm in size to several centimeters in diameter. The latter usually are collections of many nodules occurring together. These nodules have a very characteristic histology in that they are made up of a central area of fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by an area of palisading epithelial cells and fibrocytes. Surrounding this is an area of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibrocytes tissue. Detailed study of the early lesion suggests small vessel vasculitis as the initiating event,118 with deposition of immune complexes,88 and localization of HLA-DR-positive cells.9 These nodules can be observed in tendon sheaths, heart, lungs, liver, eyes, and the meninges.54 The presence of multiple nodules should alert the physician to the presence of vasculitis, and ulcerated nodules can be a source of bacteremia.

Hematologic Manifestations

Anemia is a very common presentation of RA. The prevalence depends on the stage and duration of disease, and the severity on disease activity. The cause of the anemia is multifactorial, resulting from several factors, including subclinical hemolysis, chronic blood loss as a side effect of prolonged use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The most common cause of the anemia is poor iron utilization from stores in the reticuloendothelial system and reduced erythropoietin levels. The increased production of proinflammatory cytokines in the bone marrow contributes to the anemia of chronic disease.53,69 The anemia is usually normocytic normochromic, although the picture can change depending on other complicating factors. Usually, these patients are not iron deficient, unless they have significant blood loss, and it is not always easy to distinguish between these conditions.77 When these patients schedule surgery, they may not be able to donate autologous blood for use during surgery. Recent experience with the use of synthetic erythropoietin suggests that this may be an option for some selected patients.70,71 This needs more study, because there are patients who may not respond to synthetic erythropoietin.10

Usually, the white blood cells are normal in these patients; however, about 1% of patients with RA develop a neutropenia, and splenomegaly. These patients do have an increased risk of bacterial infections and skin ulcerations. Therapy with agents used to treat RA (e.g., intramuscular gold, d-penicillamine, corticosteroids, and methotrexate) have been successful, although recently, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has also been used in small numbers of patients.13,32,63 Surgery should be avoided until the granulocytopenia has resolved. Splenectomy may help, but usually for that episode only, and is best avoided unless a life-threatening situation exists.97

Pulmonary Involvement

Pulmonary involvement in this disease is very common, with many patients with this condition being unrecognized and found to have involvement only at autopsy. In most cases, pleural involvement is asymptomatic and may be noted on incidental chest radiographs taken for other reasons (Fig. 74-5). The effusions may require aspiration, mostly for diagnostic reasons. These effusions are exudates with increased cells, protein, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Complement levels are low, and characteristically these patients have very low glucose in the effusion compared with the concomitant blood glucose. These effusions resolve with treatment of the systemic disease, leaving behind fibrosed pleura.

Rheumatoid nodules occur in the lungs in patients who are RF positive and have subcutaneous nodules. These can be single or multiple, unilateral or bilateral, or small or large. The nodules can be particularly large in patients with pneumoconiosis. Malignancy is always a consideration when a new nodule appears in the setting of a stable pulmonary picture. Without a biopsy, this possibility cannot be ruled out.127

Lungs are involved in RA patients in many different ways, although clinically, the patients may present with radiographic changes before symptoms develop. Interstitial fibrosis usually affecting the bases and spreading to the other areas of the lungs can be observed. The clinical picture is similar to that in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or the picture of interstitial fibrosis seen in connective tissue diseases. Although as many as 50% of RA patients may develop interstitial disease, only 5% are symptomatic. Pulmonary function tests and high-resolution computed tomography can aid in the recognition of small airway disease.30,43,51,68,144 Smoking has been found to be a risk factor for developing interstitial lung disease.104

Cardiac Conditions

Pericarditis, similar to pleuritis, can be found in almost 50% of the patients with RA at autopsy. The patients may be asymptomatic or may have moderate to large effusions. Fluid removed shows characteristics similar to those of pleural effusions; that is, they are exudates with increased cell counts, increased protein, LDH, low complement levels, and low glucose. Some patients present with pericardial tamponade that requires emergency aspiration or surgery. Recurrent episodes with resulting fibrosis lead to the development of constrictive pericarditis. Pericardiectomy, pericardial window, or repeated pericardial aspirations can be life-saving; without these, the mortality rates are very high.56,126

Myocarditis and endocarditis can occur in RA patients. Myocarditis is usually found at biopsy or autopsy, and rarely does it lead to congestive heart failure. More often, it presents with cardiac conduction abnormalities, as does the presence of rheumatoid nodules when localized to the conduction system, leading to first-degree, second-degree, and in some patients, third-degree heart block. Rheumatoid nodules involving the valves have been reported.16,23 Coronary vasculitis has been observed in rare cases.

Vasculitis

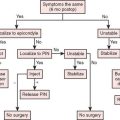

Necrotizing vasculitis of the medium-sized vessels occurs in patients who have progressive uncontrolled disease. These patients have polyarticular, nodular, erosive disease, with fever, recurrent pericarditis, cutaneous ulcerations, scleritis, and digital infarcts (Figs. 74-6 and 74-7). Laboratory studies show that these patients are anemic, and have leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and high titers of RF. The manifestations of vasculitis depend on the organ system involved. Cutaneous infarcts, ulcerations, neuropathy, bowel infarcts, digital infarcts, and, gangrene of the gallbladder, brain, heart, and peripheral nerves all can be observed.67,82 These patients are not good candidates for surgery, and it is best to delay any surgical procedures.

LABORATORY STUDIES

Laboratory studies are done to aid in diagnosis, monitor the progress and complications of disease, and assess the side effects of drugs. These tests include measuring hemoglobin, white blood cell count, differential white blood cell counts, platelet counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinatedpeptide antibody, antinuclear antibodies, liver enzymes, and renal function. Special circumstances may require specific tests, depending on the patient’s condition. Radiologic changes (Fig. 74-8) are an important measure of disease progression, and plain radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging are necessary.50 Although RF tests are positive in about 80% of patients with RA, 20% of patients with this disease are rheumatoid factor negative. Anti-IgG antibodies can also be seen in several other connective tissue diseases, with infections and malignancies, and in other states (Box 74-3); thus, one needs to interpret the results with some caution.

MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

In the past, the treatment of RA has been based on anecdotal observations, a few small short-term studies, and personal experiences.98 For many years, researchers have been proposing, trying, and then modifying different ways of approaching this disease, mainly because of a lack of curative agents. These endeavors have helped us understand the disease, the drugs we have used, and the limitations of these approaches.117,139,140 Work during the past two decades, and particularly the last decade, has led to a more scientific approach that is bearing fruit, and we are on the threshold of an era of many new agents,85 which have changed our approach as well as the outlook for patients with this disease.

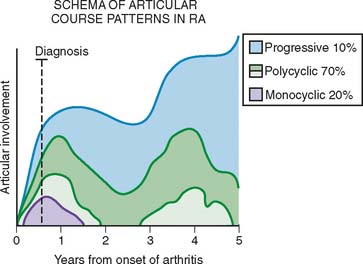

Because, at present, we do not have a cure for this disease, the goal of management is to reduce inflammation, prevent or delay disease progression, and maintain function of the joints and other organs as best as we can and for as long as possible. Although our treatments are aimed at affecting the short-term effects on the patient, the fact that RA is a chronic disease makes it very important that we keep the long-range outcome in mind. Masi65 followed a group of patients with disease of recent onset and observed that they follow several different patterns. A small group of patients (about 20%) have a monocyclic course. In these patients, the disease usually lasts less than 2 years. A small number of patients (approximately 10%) have progressive aggressive disease that does not respond to the therapies available to us today. The majority of the patients have a polycyclic course, with few actually having periods of remission, whereas others mostly go through cycles of exacerbations and partial remissions (Fig. 74-9).

FIGURE 74-9 The articular patterns seen in a prospective study of patients with early-onset rheumatoid arthritis.

(Redrawn from Masi, A. T.: Articular patterns in the early course of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Med. 75:16, 1983.)

The presence of features described in Box 74-4 have been shown to predict more aggressive disease, and these patients should be treated more aggressively.59 For years, it was believed that RA was a benign disease, but several studies have shown that the mortality of these patients is increased.7,72,78,125 Studies have shown that bony erosions occur early in this disease.37 Thus, aggressive management should be the norm rather than the exception. The management of these patients is best with the help of a rheumatologist,128,129 and such collaboration will become more important as new immunomodulators become available.

BOX 74-4 Circumstances in Which a More Aggressive Clinical Course of Rheumatoid Arthritis Should Be Suspected

It has been shown that rest is beneficial for patients with RA.51,116 It is also clear that rest without any physical activity can lead to further deconditioning and disuse atrophy of the muscles. Thus, a proper balance between physical activity and rest is very important. A physical therapy and occupational therapy26,39,40,121 program with regular monitoring should become part of the management in every case.

NSAIDs are analgesics with anti-inflammatory and antipyretic properties that have been traditionally used as initial therapy in these patients.42,47,117 Sodium salicylate was the first drug used for RA, and acetylsalicylic acid was developed for use in RA to avoid the gastrointestinal toxicity. Its mechanism of action was unknown, but later it was found to inhibit cyclooxygenase, a critical enzyme in the production of inflammatory mediators, including prostglandin E2 and F1a and thromboxane A2. It has been shown that these compounds are capable of inhibiting the activation of transcriptional nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB).57 This affects the transcription of genes of multiple molecules, including IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8. NSAIDs have many common effects, which include, in addition to cyclooxygenase inhibition, inhibition of the production of leukotrienes, superoxide, lysosomal enzyme release, lymphocyte function, and cartilage metabolism. These drugs have a mild anti-inflammatory effect on RA. They also share many of the toxicities seen with these agents, the most prominent of which are gastrointestinal. These side effects include epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting. Patients who have a history of peptic ulcer disease may experience exacerbation, with dyspepsia, indigestion, gastritis, and bleeding.89 These effects are due to suppression of prostaglandin synthesis. Misoprostol, a prostaglandin analogue, has been shown to be beneficial in these patients.114 Other side effects include liver enzyme elevations, skin rashes, headaches, drowsiness, and rarely, confusion.

Two isoenzymes of cyclooxygenase, COX-1 and COX-2, have been characterized. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in most tissues and is thought to be important for physiologic homeostasis and function of different organ systems, including the kidney, and platelets. In contrast, COX-2 is absent in most tissues and is expressed in increased amounts in inflammatory states.62,73,80,107 Although several COX-2 inhibitors were developed, currently only celecoxib is approved for use. The main issue that led to their withdrawal was concern for increased cardiovascular events occurring in patients on these drugs.11 These drugs are thought to have considerably less gastrointestinal toxicity and can be used in patients with increased risk of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal bleeding. They are also thought to have no effect on platelet function. Celecoxib is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to sulfonamides and in patients with known asthma, urticaria or allergic reactions to aspirin or other NSAIDs.

Hydrochloroquine has been used for the treatment of this disease for a long time. It is useful in patients with mild to moderate disease.27 Its mechanism of action is believed to be interference with antigen processing. This drug has been found to be safe as long as the daily dose does not exceed 6.5 mg/kg body weight. Annual eye examinations to check for retinal toxicity should be performed. Hydrochloroquine has been found to be of no additional benefit when used in combination,93 to be potentially deleterious,22 or to be beneficial.83,84

D-Penicillamine was used for years and did benefit patients22 but, because of its toxicity, has fallen out of favor. D-Penicillamine inhibits T-lymphocyte activation and decreases the formation of immune complexes. The major side effects, in addition to bone marrow toxicity, include the development of autoimmune diseases, such as myasthenia gravis, polymyositis, and Goodpasture’s syndrome. Similarly, parenteral gold has been a favorite1 until the past 10 years, when the use of methotrexate has overshadowed it. Parenteral gold has many in vitro and in vivo effects on the cellular and humoral immune response, including inhibition of antigen presentation.25 Parenteral gold use, in addition to the inconvenience of the injections, required patients to have weekly blood and urine monitoring and also exposed the patients to many side effects, some of which were serious, including bone marrow suppression, proteinuria, and skin rashes.

Methotrexate has become the standard disease-modifying agent in the treatment of RA. Several studies have shown that this drug is effective136,137 and well tolerated,94,130 and delays radiologic progression.4,131 The mechanism of action is thought to comprise both an anti-inflammatory effect and inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase. The concomitant use of folic acid has not reduced its efficacy but has decreased the frequency and severity of side effects. The concern about liver toxicity has proved not to be as serious as was the experience with psoriatic arthritis, but regular monitoring of liver function is nonetheless required.58 The issue of increased risk of infection in RA patients receiving methotrexate at the time of surgery has been controversial, because reports of both an increased risk19,24 and the lack thereof55 have been published. It has been proposed that stopping methotrexate therapy for 2 weeks before surgery is reasonable.20 Several drugs have been used successfully in combination.83,84

Leflunomide inhibits the enzyme dihydro-orotate dehydrogenase, thus leading to inhibition of pyrimidine synthesis. This inhibition, in turn, inhibits both T- and B-cell function.38,74 This oral drug has a long half-life of 7 to 8 days, which can increase over a longer time of dosing to as much as 28 days. It is excreted via the kidneys and in the feces in a 1 : 1 ratio. Biliary excretion and reabsorption are major reasons for the prolonged half-life, and female patients planning to have children need treatment with cholestyramine to rid the leflunomide from the body. Leflunomide has been shown to be effective in patients with RA and can be used alone or in combination with methotrexate. It seems to be well tolerated, with the major side effects being gastrointestinal disturbances, skin rashes, weight loss, and alopecia. Gastrointestinal disturbances include abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, gastritis, and occasionally, vomiting.

The past 10 years have seen a revolution in the management of RA.135 New biologic agents targeting various inflammatory molecules have been shown to successfully control this disease and to retard the damage that accompanies it. Several new products aim at blocking tumor necrosis factor (TNF), one of the proinflammatory cytokines produced during the inflammatory process in the joints.

Etanercept is a dimeric recombinant fusion protein that consists of the human 75-kd tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) fused with the Fc portion of human IgG1. It binds to TNF, blocking its ability to bind to cell surface TNFRs. It is given parenterally once or twice a week and is one of the few drugs that shows a response within a couple of weeks.76,132 Infliximab122 and adalimumab18 are monoclonal antibodies capable of binding TNF in solution as well as on the cell surface. The former is a chimeric molecule given as an intravenous infusion at 6- to 8-week intervals while the latter is a wholely human molecule and given subcutaneously at weekly or biweekly intervals. All of these agents can be used along with methotrexate. This combination does not have any increased toxicity and, in fact, may have additional benefit than when given alone. They are generally well tolerated. Etanercept and adalimumab can be associated with local injection site reactions; most of these require no treatment. Other side effects have included upper respiratory infections, headaches, rhinitis, dizziness, cough, and dyspepsia, in descending order of frequency. Infliximab is associated with infusion reactions including rash, urticaria, fever, chest heaviness, and rarely, anaphylactic reactions. They are contraindicated in patients with sepsis and during pregnancy. All of these conditions carry a risk of infections including reactivation of tuberculosis and fungal diseases. Because of this problem, all patients are screened for exposure to tuberculosis before therapy is initiated. It has also been observed that patients on these drugs do have a slightly higher risk of lymphoproliferative malignancies.15 This is in the background of increased lymphoproliferative malignancies in patients with RA, as well as treatment with methotrexate. Other rare side effects include demyelinating diseases in rare patients.

Other immunomodulators that are approved for treatment of RA include anakinra, a human recombinant anti-IL-1 receptor antagonist, which is given by daily subcutaneous injections. The benefits on the disease are modest.29 Abatacept is a recombinant fusion protein made up of the extracellular domain of CTLA-4 and Fc portion of human IgG1. This prevents the antigen-presenting cells from activating the T cells. Like anti-TNF agents, abatacept has been shown to be effective in RA including patients refractory to methotrexate and anti-TNF agents.41 Rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody long used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, has been found to be effective in treating RA and has been approved for use. This is the only biologic agent approved for treatment of RA that targets the B cells.34,35

1 Abeles M., Urman J.D., Weinstein A. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with gold. South. Med. J. 1977;70:604.

2 Aho K., Koskenvuo M., Tuominen J., Kaprio J. Occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis in a nationwide series of twins. J. Rheumatol. 1986;13:899.

3 Alarcon G.S. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1995;21:589.

4 Alarcon G.S., Lopez-Mandez A., Walter J., Boerbooms A.M., Russell A.S., Furst D.E., Rau R., Drosos A.A., Bartolucci A.A. Radiographic evidence of disease progression in methotrexate treated and nonmethotrexate disease modifying antirheumatic drug treated rheumatoid arthritis patients: A meta-analysis [see comments]. J. Rheumatol. 1992;19:1868.

5 Alexander G.J., Hortas C., Bacon P.A. Bed rest, activity and the inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1983;22:134.

6 Alspaugh M.A., Henle G., Lennette E.T., Henle W. Elevated levels of antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus antigens in sera and synovial fluids of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 1981;67:1134.

7 Anderson S.T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: Do age and gender make a difference? Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;25:291.

8 Arnett F.C., Edwarthy S.M., Bloch D.A., McShane D.J., Friès J.F., Cooper N.S., Healey L.A., Kaplan S.R., Liang M.H., Luthra H.S., et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315.

9 Athanasou N.A., Quinn J., McGee J.O. Immunohistology of rheumatoid nodules and rheumatoid synovium. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1988;47:398.

10 Baer A.N. Blunted erythropoietin response to anaemia in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Haematol. 1987;66:559.

11 Baigent C., Patrono C. Selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors, aspirin and cardiovascular disease: a reappraisal. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:12.

12 Barry M.A., Purser J., Hazleman R., McLean A., Hazleman B.L. Effect of energy conservation and joint protection education in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1994;33:1171.

13 Bhalla K., Ross R., Jeter E., Madyastha P., Stuart R. G-CSF improves granulocytopenia in Felty’s syndrome without flare-up of arthritis [letter]. Am. J. Hematol. 1993;42:230.

14 Bland J., Eddy W. Hemiplegia and rheumatoid hemiarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1968;11:72.

15 Bongartz T., Sutton A.J., Sweeting M.J., Buchan I., Matteson E.L., Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies. J. A. M. A. 2006;295:2275.

16 Bortolotti U., Cassarotto D., Gallucci V., Gasparotto G., Thiene G. Mitral and aortic valve replacement in valvular rheumatoid heart disease. Chest. 1978;73:427.

17 Brasington R.D.Jr. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In Hochberg M.C., Silman A.J., Smolen J.S., Weinblatt M.E., Weissman M.H., editors: Rheumatology, 4th ed., St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

18 Breedveld F.C., Weisman M.H., Kavanaugh A.F., Cohen S.B., Pavelka K., van Vollenhoven R., Sharp J., Perez J.L., Spencer-Green G.T. The PREMIER study: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who have not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:26.

19 Bridges S.L.Jr., Lopez-Mendez A., Han K.H., Tracy I.C., Alarcón G.S. Should methotrexate be discontinued before elective orthopedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? J. Rheumatol. 1991;18:984.

20 Bridges S.L.Jr., Moreland L.W. Perioperative use of methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing orthopedic surgery. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1997;23:981.

21 Bromley J., Unsworth A., Haslock I. Changes in stiffness following short- and long-term application of standard physiotherapeutic techniques. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1994;33:555.

22 Bunch T.W., O’Duffy J.D., Tompkins R.B., O’Fallon W.M. Controlled trial of hydroxychloroquine and D-penicillamine singly and in combination in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:267.

23 Carpenter D.F., Golden A., Roberts W.C. Quadrivalvular rheumatoid heart disease associated with left bundle branch block. Am. J. Med. 1967;43:922.

24 Carpenter M.T., West S.G., Vogelgesang S.A., Casey Jones D.E. Postoperative joint infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients on methotrexate therapy. Orthopedics. 1996;19:207.

25 Champion G.D., Graham G.G., Ziegler J.B. The gold complexes. Baillieres Clin. Rheumatol. 1990;4:491.

26 Chan M.L. The role of occupational therapy in rheumatoid arthritis management. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 1998;27:120.

27 Clark P., Casas E., Tugwell P., Medina C., Gheno C., Tenorio G., Orozco J.A. Hydroxychloroquine compared with placebo in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial [see comments]. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993;119:1067.

28 Cohen B.J., Buckley M.M., Clewley J.P., Jones V.E., Puttick A.H., Jacoby A.K. Human parvovirus infection in early rheumatoid and inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1986;45:832.

29 Cohen S.B., Moreland L.W., Cush J.J., Greenwald M.W., Block S., Shergy W.J., Hanrahan P.S., Kraishi M.M., Patel A., Sun G., Bear M.B., 990145 Study Group. A multicentre, double blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial of anakinra (Kineret), a recombinant interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with background methotrexate. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004;63:1062.

30 Cortet B., Perez T., Roux N., Duquesnoy B., Delcambre B., Rémy-Jardin M. Pulmonary function tests and high-resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1997;56:596.

31 Deighton C.M., Gray J., Bint A.J. Specificity of the Proteus antibody response in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis.. 1992;51:1206.

32 Dillon A.M., Luthra H.S., Conn D.L., Ferguson R.H. Parenteral gold therapy in the Felty syndrome: Experience with 20 patients. Medicine. 1986;65:107.

33 Dorfman H.D., Siegel H.L., Perry M.C., Oxenhandler R. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the synovium simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:155.

34 Edwards J.C., Szczepanski L., Szechinski J., Filipowicz-Sosnowska A., Emery P., Close D.R., Stevens R.M., Shaw T. Efficacy of B-cell targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2572.

35 Emery P., Fleischmann R., Filipowicz-Sosnowska A., Schechtman J., Szczepanski L., Kavanaugh A., Racewicz A.J., van Vollenhoven R.F., Li N.F., Agarwal S., Hessey E.W., Shaw T.M. DANCER Study Group.: The efficacy and safety of rituximabin patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate treatment: results of a phase IIb randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. Arthritis Rheum.. 2006;54:1390.

36 Fahalli S., Halla J.T., Hardin J.G. Onset patterns of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Res. 1983;31:650A.

37 Fuchs H.A., Kaye J.J., Callahan L.F., Nance E.P., Pincus T. Evidence of significant radiographic damage in rheumatoid arthritis within the first 2 years of disease. J. Rheum. 1989;16:585.

38 Furst D. Cyclosporine, leflunomide and nitrogen mustard. Bull. Clin. Rheumatol. 1995;9:711.

39 Furst G.P., Gerber L.H., Smith C.C., Fisher S., Shulman B. A program for improving energy conservation behaviors in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1987;41:102.

40 Ganz S.B., Harris L.L. General overview of rehabilitation in the rheumatoid patient. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1998;24:181.

41 Genovese M.C., Becker J.C., Schiff M., Luggen M., Sherrer Y., Kremer J., Birbara C., Box J., Natarajan K., Nuamah I., Li T., Aranda R., Hagerty D.T., Dougados M. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1114.

42 Gibson T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Another look. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1988;27:87.

43 Gilligan D.M., O’Connor C.M., Ward K., Moloney D., Bresnihan B., FitzGerald M.X. Bronchoalveolar lavage in patients with mild and severe rheumatoid lung disease. Thorax. 1990;45:591.

44 Glick E.N. Asymmetrical rheumatoid arthritis after poliomyelitis. B. M. J. 1967;3:26.

45 Goronzy J.J., Weyand C.M. Interplay of T lymphocytes and HLA-DR molecules in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 1993;5:169.

46 Gregersen P.K., Silver J., Winchester R.J. The shared epitope hypothesis: An approach to understanding the molecular genetics of susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1205.

47 Guidelines for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:713.

48 Gulko P.S., Kawahito Y., Remmers E.F., Reese V.R., Wang J., Dracheva S.V., Ge L., Longman R.E., Shepard J.S., Cannon G.W., Sawitzke A.D., Wilder R.L., Griffiths M.M. Identification of a new non-major histocompatibility complex genetic locus on chromosome 2 that controls disease severity in collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:2122.

49 Hasty K.A., Reife P.A., Kang A.H., Stuart J.M. The role of stromelysin in the cartilage destruction that accompanies inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:388.

50 Ho C.P., Sartoris D.J. Magnetic resonance imaging of the elbow. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1991;17:705.

51 Ippolito J.A., Palmer L., Spector S., Kane P.B., Gorevic P.D. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia and rheumatoid arthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;23:70.

52 Jawaheer D., Thomson W., MacGregor A.J., Carthy D., Davidson J., Dyer P.A., Silman A.J., Ollier W.E. “Homozygosity” for the HLA-DR shared epitope contributes the highest risk for rheumatoid arthritis concordance in identical twins. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:681.

53 Jongen-Lavrencic M., Peeters H.R., Wognum A., Vreugdenhil G., Breedreld F.C., Swaak A.J. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines in bone marrow of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and anemia of chronic disease. J. Rheumatol. 1997;24:1504.

54 Kamio N., Kuramochi S., Wang R.J., Hirose S., Hosoda Y. Rheumatoid arthritis complicated by pachy- and leptomeningeal rheumatoid nodule-like granulomas and systemic vasculitis. Pathol. Int. 1996;46:526.

55 Kasdan M.L., June L. Postoperative results of rheumatoid arthritis patients on methotrexate at the time of reconstructive surgery of the hand. Orthopedics. 1993;16:1233.

56 Kennedy W.P., Partridge R.E., Matthews M.B. Rheumatoid pericarditis with cardiac failure treated by pericardiectomy. Br. Heart J. 1966;28:602.

57 Kopp E., Ghosh S. Inhibition of NF-kB by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science. 1994;265:956.

58 Kremer J.M., Alarcon G.S., Lightfoot R.W.Jr., Willkens R.F., Furst D.E., Williams H.J., Dent P.B., Weinblatt M.E. Methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis: Suggested guidelines for monitoring liver toxicity. American College of Rheumatology [see comments]. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:316.

59 Lard L.R., Visser H., Speyer I., vander Horst-Bruinsma I.E., Zwinderman A.H., Breedveld F.C., Hazes J.M. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparision of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am. J. Med. 2001;111:446.

60 Leroux J.Y., Poole A.R., Webber C., Vipparti V., Choi H.U., Rosenberg L.C., Bannerjee S. Characterization of proteoglycan-reactive T cell lines and hybridomas from mice with proteoglycan-induced arthritis. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2090.

61 Levine J.D., Goetzl E.J., Basbaum A.I. Contribution of the nervous system to the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis and other polyarthritides. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1987;13:369.

62 Lipsky P.E. Progress toward a new class of therapeutics: Selective COX-2 inhibition. J. Rheumatol. 1997;24(Suppl. 49):1.

63 Luthra H.S. Felty’s syndrome: A therapeutic dilemma? [editorial] [see comments]. J. Rheumatol. 1989;16:864.

64 Maini R., Feldman M. Immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Maddison P.J., Isenberg D.A., Woo P., Glass D.N., editors. Oxford Textbook of Rheumatology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998:983.

65 Masi A.T. Articular patterns in the early course of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Med. 1983;75:16.

66 Massardo L., Jacobelli S., Rodriguez L., River S., Gonzalez A., Naschetti R. Weak association between HLA-DR4 and rheumatoid arthritis in Chilean patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1990;49:290.

67 McCurley T.L., Collins R.D. Intestinal infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: Three cases due to unusual obliterative vascular lesions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1984;108:125.

68 McDonagh J., Greaves M., Wright A.R., Heycock C., Owen J.P., Kelly C. High-resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and interstitial lung disease [see comments]. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1994;33:118.

69 Means R.T., Krantz S.B. Progress in understanding the pathogenesis of the anemia of chronic disease. Blood. 1992;80:1639.

70 Mercuriali F., Gualtieri G., Sinigaglia L., Inghilleri G., Biffi E., Vinci A., Colotti M.T., Barosi G., Lambertengh Deliliers G. Use of recombinant human erythropoietin to assist autologous blood donation by anemic rheumatoid arthritis patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Transfusion. 1994;34:501.

71 Mercuriali F. Epotein alfa for autologous blood donation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and concomitant anemia. Semin. Hematol. 1997;33(2 Suppl 2):18. discussion 21

72 Mitchell D.M., Spitz P.W., Young D.Y., Bloch D.A., McShane D.J., Fries J.F. Survival, prognosis, and causes of death in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:706.

73 Mitchell J.A., Akarasereenont P., Thiemermann C., Flower R.J., Vane J.R. Selectivity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as inhibitors of constitutive and inducible cyclooxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;90:11693.

74 Mladenovic V., Domljan Z., Rozman B., Jajic I., Mihajlovic D., Dordevic J., Popovic M., Dimitrijevic M., Zivkovic M., Campion G., et al. Safety and effectiveness of leflunomide in the treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1595.

75 Morales-Torres J. Antiquity of rheumatoid arthritis. In Hochberg M.C., Silman A.J., Smolen J.S., Weinblatt M.E., Weissman M.H., editors: Rheumatology, 4th ed., St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

76 Moreland L.W., Baumgartner S.W., Schiff M.H., Tindall E.A., Fleischmann R.M., Weaver A.L., Ettlinger R.E., Cohen S., Koopman W.J., Mohler K., Widmer M.B., Blosch C.M. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75) fusion protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;337:141.

77 Mulherin D., Skelly M., Saunders A., McCarthy D., O’Donoghue D., Fitzgerald O., Bresnihan B., Mulcahy H. The diagnosis of iron deficiency in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and anemia: An algorithm using simple laboratory measures [see comments]. J. Rheumatol. 1996;23:237.

78 Myllykangas-Luosujarvi R.A., Aho K., Isomaki H.A. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;25:193.

79 Nabozny G.H., Baisch J.M., Cheng S., Cosgrove D., Griffiths M.M., Luthra H.S., David C.S. HLA-DQ8 transgenic mice are highly susceptible to collagen-induced arthritis: A novel model for human polyarthritis. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:27.

80 Needleman P., Isakson P.C. The discovery and function of COX-2. J. Rheumatol. 1997;24(Suppl 49):6.

81 Nepom G.T., Byers P., Seyfried C., Healey L.A., Wilske K.R., Stage D., Nepom B.S. HLA genes associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:15.

82 Newbold K.M., Allum W.H., Downing R., Symmons D.P., Oates G.D. Vasculitis of the gall bladder in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 1987;6:287.

83 O’Dell J.R., Haire C.E., Erikson N., Drymalski W., Palmer W., Eckhoff P.J., Garwood V., Maloley P., Klassen L.W., Wees S., Klein H., Moore G.F. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate alone, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or a combination of all three medications [see comments]. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:1287.

84 O’Dell J.R., Haire C.E., Erikson N., Haire C., Erikson N., Drymalski W., Palmer W., Maloley P., Klassen L.W., Wees S., Moore G.F. Efficacy of triple DMARD therapy in patients with RA with suboptimal response to methotrexate. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 1996;44:72.

85 Oliver A.M., St. Clair E.W. Rheumatoid arthritis C. Treatment and assessment. In: Klippel J.H., Stone J.H., Crofford L.J., White P.H., editors. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. New York: Springer, 2008.

86 Ollier W.E., MacGregor A. Genetic epidemiology of rheumatoid disease. Br. Med. Bull. 1995;51:267.

87 Ollier W., Thomson W. Population genetics of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1992;18:741.

88 Palmer D.G. The anatomy of the rheumatoid lesion. Br. Med. Bull. 1995;51:286.

89 Patrono C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In Hochberg M.C., Silman A.J., Smolen J.S., Weinblatt M.E., Weissman M.H., editors: Rheumatology, 4th ed., St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

90 Pereira da Silva J.A., Carmo-Fonseca M. Peptide containing nerves in human synovium: Immunohistochemical evidence for decreased innervation in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 1990;17:1592.

91 Peterson L.F., Janes J.M. Surgery of the rheumatoid elbow. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1971;2:667.

92 Poole A.R., Dieppe P. Biological markers in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;23(6 Suppl 2):17.

93 Porter D.R., Capell H.A., Hunter J. Combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: No benefit of addition of hydroxychloroquine to patients with a suboptimal response to intramuscular gold therapy. J. Rheumatol. 1993;20:645.

94 Rau R., Herborn G., Menninger H., Blechschmidt J. Comparison of intramuscular methotrexate and gold sodium thiomalate in the treatment of early erosive rheumatoid arthritis: 12-month data of a double-blind parallel study of 174 patients. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1997;36:345.

95 Remmers E.F., Longman R.E., Du Y., O’Hare A., Cannon G.W., Griffiths M.M., Wilder R.L. A genome scan localizes five non-MHC loci controlling collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:82.

96 Resnick D. Thoracolumbar spine abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis [letter]. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1978;37:389.

97 Riley S.M., Aldrete J.S. Role of splenectomy in Felty’s syndrome. Am. J. Surg. 1975;130:51.

98 Rodnan G.P., Benedek T.G. The early history of antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 1970;13:145.

99 Rosner I. Rheumatoid-like arthritis associated with hepatitis. C. J. Clin. Rheumat. 1995;1:182.

100 Rothschild B.M., Woods R.J. Does rheumatoid polyarthritis come from the New World? Rev. Rhum. Maladies Osteo-Articulaires. 1990;57:271.

101 Rothschild B.M., Woods R.J. Symmetrical erosive disease in Archaic Indians: The origin of rheumatoid arthritis in the New World? Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;19:278.

102 Rothschild B.M., Turner K.R., DeLuca M.A. Symmetrical erosive peripheral polyarthritis in the Late Archaic Period of Alabama. Science. 1988;241:1498.

103 Rothschild B.M., Woods R.J., Rothschild C., Sebes J.I. Geographic distribution of rheumatoid arthritis in ancient North America: Implications for pathogenesis [see comments]. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;22:181.

104 Saag K.G., Kolluri S., Koehnke R.K., Georgou T.A., Rachow J.W., Hunninghake G.W., Schwartz D.A. Rheumatoid arthritis lung disease: Determinants of radiographic and physiologic abnormalities. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1711.

105 Sakai K., Matsuno H., Tsuji H., Tohyama M. Substance P receptor (NK1) gene expression in synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1998;27:135.

106 Sattar M.A., al-Saffar M., Guindi R.T., Sugathan T.N., White A.G., Behloehari K. Histocompatibility antigens (A, B, C, and DR) in Arabs with rheumatoid arthritis. Dis. Markers. 1990;8:11.

107 Seibert K., Zhang Y., Leahy K., Hauser S., Masferrer J., Perkins W., Lee L., Isakson P. Pharmacological and biochemical demonstration of the role of cyclooxygenase 2 in inflammation and pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:12013.

108 Shapiro J.S. A new factor in the etiology of ulnar drift. Clin. Orthoped. Rel. Res. 1970;68:32.

109 Short C.L. The antiquity of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:193.

110 Silman A.J. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Apmis. 1994;102:721.

111 Silman A.J. Parity status and the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. (Copenhagen). 1992;28:228.

112 Silman A.J., Hochberg M.C. Epidemiology of the Rheumatic Diseases. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

113 Silman A.J., Newman J., MacGregor A.J. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: Results from a nationwide study of disease-discordant twins [see comments]. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:732.

114 Silverstein F.E., Graham D.Y., Senior J.R., Davies H.W., Struthers B.J., Bittman R.M., Geis G.S. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995;123:241.

115 Sims-Williams H., Jayson M.I., Baddeley H. Rheumatoid involvement of the lumbar spine. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1977;36:524.

116 Smith R.D., Polley H.F. Rest therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1978;53:141.

117 Smyth C.J. Therapy of rheumatoid arthritis: A pyramidal plan. Postgrad. Med. 1972;51:31.

118 Sokoloff L., McCluskey R., Bunim J. Vascularity of the early subcutaneous nodule of rheumatoid arthritis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1953;355:475.

119 Starkebaum G. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Science Med. 1998;5:6.

120 Stastny P. The association of B-cell alloantigen DRw4 with rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978;298:869.

121 Stastny P., Ball E.J., Khan M.A., Olsen N.J., Pincus T., Gao X. HLA-DR4 and other genetic markers in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1988;27(Suppl 2):132.

122 St. Clair E.W., van der Heijde D.M., Smolen J.S., Maini R.N., Bathon J.M., Emery P., Keystone E., Schiff M., Kalden J.R., Wang B., Dewoody K., Weiss R., Baker D. Active-Controlled Study of Patients Receiving Infliximab for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis of Early Onset Study Group: Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3432.

123 Swezey R.L., Fiegenberg D.S. Inappropriate intrinsic muscle action in the rheumatoid hand. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1971;30:619.

124 Thompson M., Bywaters E.G.L. Unilateral rheumatoid arthritis following hemiplegia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1962;21:370.

125 Vandenbroucke J.P., Hazevoet H.M., Cats A. Survival and cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis: A 25-year prospective follow-up. J. Rheumatol. 1984;11:158.

126 Wallberg-Jonsson S., Ohman M.L., Dahlqvist S.R. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis in Northern Sweden. J. Rheumatol. 1997;24:445.

127 Walters M.N., Ojeda V.J. Pleuropulmonary necrobiotic rheumatoid nodules: A review and clinicopathological study of six patients. Med. J. Austral. 1986;144:648.

128 Ward M.M., Leigh P., Fries J.F. Progression of functional disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Associations with rheumatology subspeciality care. Arch. Intern. Med. 1993;153:2229.

129 Ward M.M., Lubeck D., Leigh J.P. Long-term health outcomes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated in managed care and fee-for-service practice settings [see comments]. J. Rheumatol. 1998;25:641.

130 Weinblatt M.E., Maier A.L., Fraser P.A., Coblyn J.S. Long-term prospective study of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: Conclusion after 132 months of therapy. J. Rheumatol. 1998;25:238.

131 Weinblatt M.E., Polisson R., Blotner S.D., Sosman J.L., Aliabadi P., Baker N., Weissman B.N. The effects of drug therapy on radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a 36-week randomized trial comparing methotrexate and auranofin [published erratum appears in Arthritis Rheum. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:613. 1993 36:1028] [see comments].

132 Weinblatt M.E., Kremer J.M., Bankhurst A.D., Bulpitt K.J., Fleischmann R.M., Fox R.I., Jackson C.G., Lange M., Burge D.J. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate [see comments]. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:253.

133 Weyand C.M., Goronzy J.J. Inherited and noninherited risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 1995;7:206.

134 Weyand C.M., Goronzy J.J. Pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Med. Clin. North Am. 1997;81:29.

135 Weyand C.M., Klimiuk P.A., Goronzy J.J. Heterogeneity of rheumatoid arthritis: From phenotypes to genotypes. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 1998;20(1-2):5.

136 Williams H.J., Willkens R.F., Samuelson C.O.Jr., Alarcón G.S., Guttadauria M., Yarboro C., Polisson R.P., Weiner S.R., Luggen M.E., Billingsley L.M., et al. Comparison of low-dose oral pulse methotrexate and placebo in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:721.

137 Willkens R.F. Resolve: Methotrexate is the drug of choice after NSAIDs in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;20:76.

138 Willkens R.F., Nepom G.T., Marks C.R., Nettles J.W., Nepom B.S. Associations of HLA-Dw 16 with rheumatoid arthritis in Yakima Indians. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:43.

139 Wilske K.R. Inverting the therapeutic pyramid: Observations and recommendations on new directions in rheumatoid arthritis therapy based on the author’s experience. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;23(2 Suppl 1):11.

140 Wilske K.R., Healey L.A. Remodeling the pyramid: A concept whose time has come. J. Rheumatol. 1989;16:565.

141 Winrow V.R., Ragno S., Morris C.J., Colston M.J., Mascagni P., Leosi F., Gromo G., Coates A.R., Blake D.R. Arthritogenic potential of the 65 kDa stress protein: An experimental model. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1994;53:197.

142 Wollheim F. Rheumatoid arthritis: The clinical picture. In: Maddison P.J., Isenberg D.A., Woo P., Glass D.N., editors. Oxford Textbook of Rheumatology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998:1004.

143 Woolley D.E., Crossley M.J., Evanson J.M. Collagenase at sites of cartilage erosion in the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:1231.

144 Yousem S.A., Colby T.V., Carrington C.B. Lung biopsy in rheumatoid arthritis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1985;131:770.