Chapter 57 Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Using Autologous Hamstring Tendons

Introduction

Due to the high incidence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and the tremendous socioeconomic importance of this injury, there continues to be intensive research into basic science, pathology, and reconstruction techniques of the ACL. Thus a wide range of techniques for ACL reconstruction and numerous different fixation devices are available. Nevertheless, the perfect technique for ACL reconstruction still seems to be elusive, demonstrated by the fact that primary ACL reconstruction is not successful in restoring normal knee kinematics in all cases. According to the current literature, revision surgery after primary ACL reconstruction is performed in 3% to 25% of cases due to long-term graft failure as well as unsatisfactory outcome (loss of range of motion, locking, effusion, pain, etc.).1–3

It is generally believed that revision ACL reconstruction is a challenging procedure requiring experience in a variety of different surgical techniques and graft fixation techniques. Revision ACL reconstruction might be even more demanding if surgical mistakes have been made during primary reconstruction, if a double-bundle reconstruction was performed, or if a severe tunnel enlargement has developed. Whether revision ACL reconstruction can be performed as a single- or two-staged procedure mainly depends on tunnel and hardware management.2,4,5

It is generally believed that the overall clinical outcome after revision ACL reconstruction is inferior compared with primary procedures.2,5–13 Thus the importance of counseling the patient preoperatively about less satisfactory results than in primary ACL reconstruction must be emphasized. However, taking an inferior result into account, as described in the current literature, one might be quickly less optimistic about producing an optimal result after revision reconstruction. Therefore it should be our primary goal to be as perfect as possible with diagnostics and decision making as well as surgery in order to offer the patient a successful outcome, as in primary reconstruction. Thus we strongly recommend the use of a clearly defined diagnostic and treatment algorithm in order to fulfill that goal.

Failure Analysis

Radiographic Evaluation

The performed radiographs should routinely include the following:

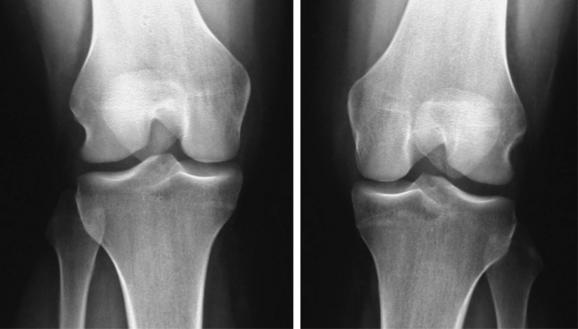

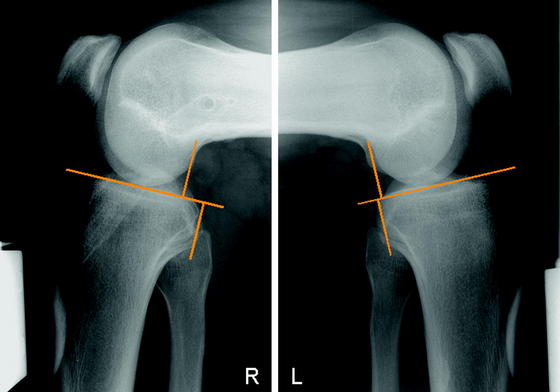

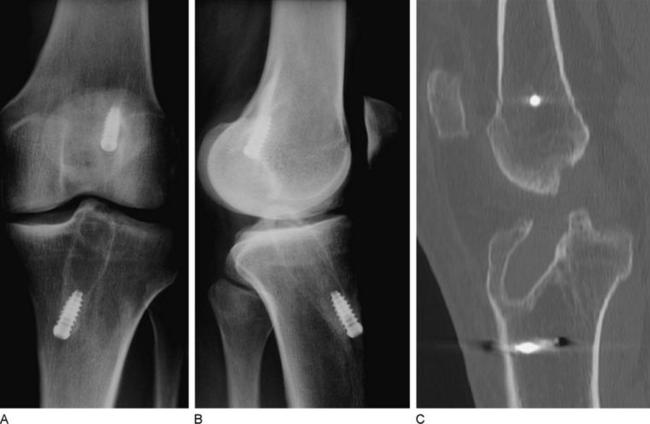

In cases with clinically apparent varus or valgus malalignment or posterolateral insufficiency, long standing radiographs should be made to assess the need for additional axis correction. In case of tunnel enlargement, a computed tomography (CT) scan is indicated to clearly analyze its dimensions (Fig. 57-6).

Concomitant Pathology

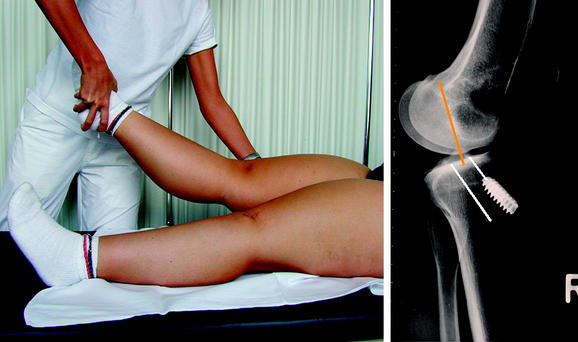

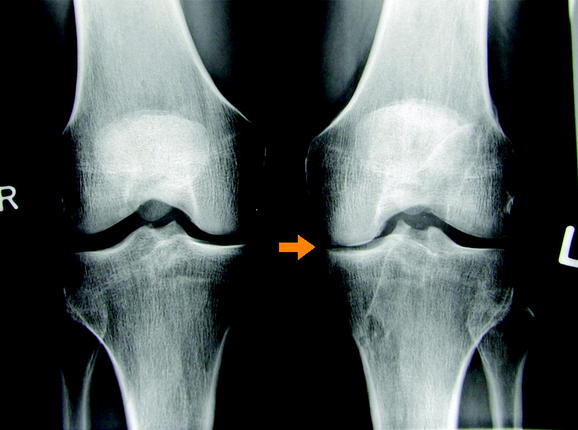

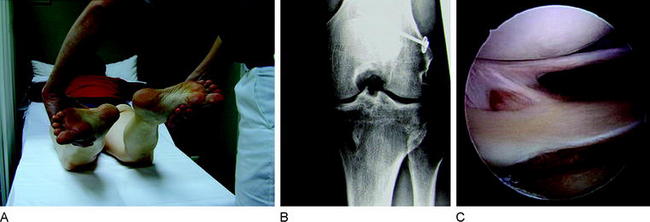

The stabilizing functions of the single knee ligaments are not strictly separated. Secondary graft failure can often be found in combination with unrecognized concomitant ligament pathology, even in perfect ACL reconstructed knees. In fact, all the knee restraints work as a unit and normal knee stability can only be achieved if all ligaments are intact. In cases of ACL insufficiency, secondary restraints such as the posterior oblique ligament (POL) and the posterior horn of the medial meniscus might compensate for the instability. However, if there is medial collateral ligament (MCL) insufficiency (especially POL) and/or a subtotal medial meniscus loss, the freshly reconstructed ACL might not be able to absorb the particular forces and might stretch out. In principle this can be applied to any other combination of ligamentous knee injuries. Thus all directions of knee instability, especially rotatory instabilities, have to be assessed carefully during clinical (and radiological) examination. In detail these instabilities include the PCL (see Fig. 57-5), lateral or posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI; Fig. 57-7), anteromedial rotatory instability (AMRI), anterolateral rotatory instabilities (ALRI), and MCL or posteromedial rotatory instabilities (PMRI; Fig. 57-8).

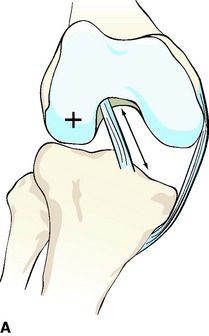

Now we have to question which of these concomitant pathologies needs to be addressed surgically in revision procedures. If an AMRI or PMRI is present, a certain grade of instability might be left untreated in a revision case, as the influence of these instabilities is still not clearly defined and the outcome of surgery (MCL, POL, PMRI) often is unsatisfactory. If there is severe valgus opening, a posteromedial reefing (e.g., that according to Hughston) or a ligament grafting could be done.17,18 Whether a microperforation of the medial structures according to Rosenberg is successful in these conditions needs further clinical research. In cases of lateral instabilities including PLRI and ALRI, the situation is different. In former years a grossly positive pivot shift was often treated by an additional anterolateral stabilization such as according to Lemaire19–21 (Fig. 57-9). At present, an additional extraarticular procedure is not routinely recommended; however, in revision reconstructions one might make an exception. In cases with only a slight anterior translation combined with a gross pivot shift, one might consider an additional anterolateral stabilization in selected cases if the femoral ACL graft position is lateral (10-o’clock position). If, for example, a revision reconstruction with lateral femoral tunnel placement does not restore the pivot shift during revision surgery, one might consider an additional Lemaire procedure in these rare cases. However, only one peripheral concomitant pathology should always be addressed during ACL revision reconstruction, the PLRI (see Fig. 57-7), because the high failure rate of ACL reconstruction in combination with a PLRI is well known.22–24

In principle, single-staged repair of any of these combinations is possible if boundary conditions allow for the planned surgical procedure. One major exception has to be assessed carefully, which is clinically apparent as the “fixed posterior subluxation.” Normally this phenomenon is discussed in the context of PCL insufficiency and repair. However, it has been demonstrated that approximately 15% of all patients with PCL insufficiency underwent previous isolated ACL reconstruction.25 The reason for this failure often is a wrongly interpreted positive Lachman test, which in the case of PCL insufficiency and an intact ACL might demonstrate an increased way with a firm endpoint. Thus it is of great importance to always evaluate the PCL in ACL deficient knees. Additionally, the PCL deficient knee easily subluxates to posterior during ACL graft fixation, which might lead to a fixed posterior subluxation.26 This results in changed femorotibial biomechanics and high patellofemoral reaction forces. Patients who demonstrate a fixed posterior subluxation often suffer from very early and severe degenerative lesions. If a fixed posterior subluxation is diagnosed, the initial treatment includes the wear of a special brace (PTS Brace, Medi GmbH, Bayreuth, Germany), which pushes the tibia to anterior.25,26 Depending on boundary conditions and ligamentous instability, revision ACL reconstruction as well as PCL reconstruction might be indicated.26

Hardware Management

Hardware Removal

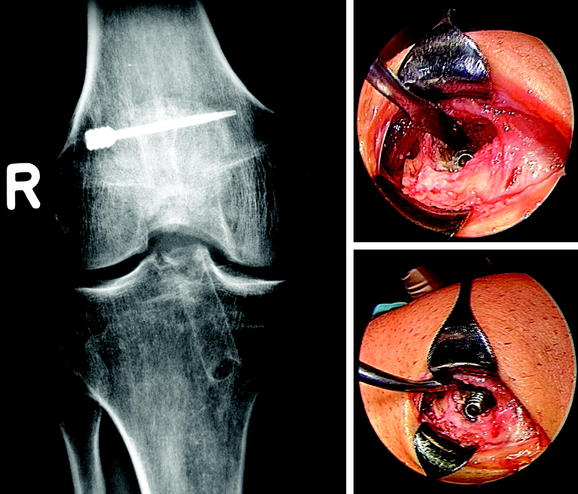

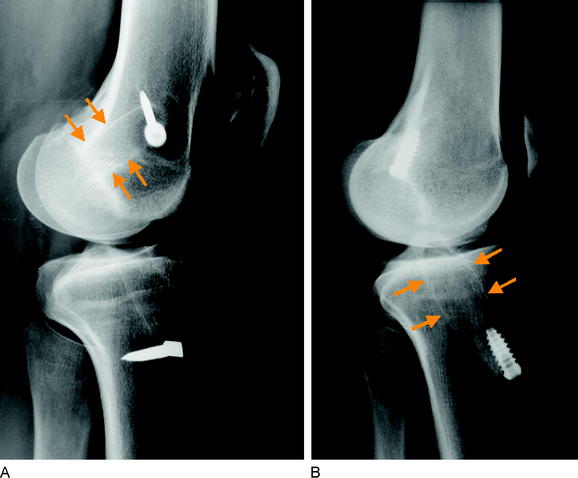

Hardware removal might result in distinct postoperative morbidity or large bone defects (e.g., transfixation devices or deeply countersunk metal interference screws) (Fig. 57-10). Thus older fixation devices need to be removed only if they compromise new tunnel placement or graft fixation. If metal fixation devices do not completely affect new tunnel placement, they often can be pushed into the cancellous bone by serial tunnel dilation (Fig. 57-11). Biodegradable interference screws, even if they are not degraded during revision surgery, do not need to be removed because they can easily be overdrilled. Only a careful washout of particles from the joint cavity is needed to prevent later chondral lesions and/or inflammatory response. Hardware removal also should be performed if older fixation devices clearly are responsible for local pain or discomfort (Fig. 57-12).

Due to the variability of fixation devices available on the market, hardware removal can be extremely frustrating. Attempts to remove hardware using instruments that do not fit exactly to the fixation devices might result in large bone defects and iatrogenic lesions. Thus in our experience a set of specially designed revision screwdrivers can be very helpful. These instruments fit to most of the fixation devices available (Fig. 57-13).

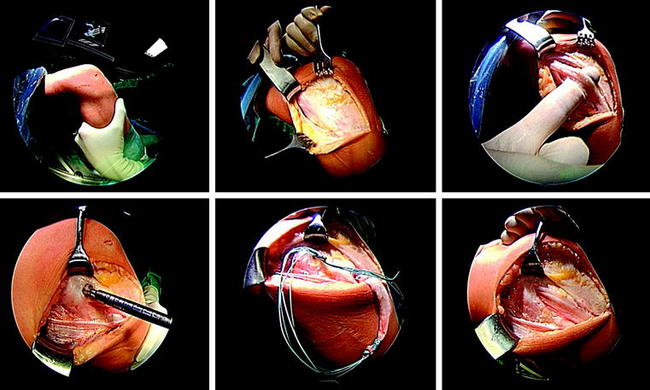

Fig. 57-13 A set of specially designed revision screwdrivers.

(By permission of KarlStorz, Tuttlingen, Germany.)

Most of the standard metallic interference screws can be removed nicely in a single-staged procedure. However, if metal screws have been deeply countersunk (tibial site, femoral outside-in) and need to be removed for revision reconstruction, one might consider a two-staged procedure because the removal in these circumstances could be very time consuming. Moreover, if the removal of metal implants and ACL revision reconstruction are planned in the same procedure, the patient should be informed that it might be possible to end in a two-staged procedure if problems occur during implant removal. Sometimes problems occur during surgery; for example, if there is an incompletely incorrect tunnel (see later discussion) and the metal screw is large (9 × 25 mm), the additional removal of that screw might lead to a large bone defect, communicating with the old and desired new tunnel. In these cases, bone grafting in a two-staged procedure might be necessary. Sometimes the removal of metallic cross-pin devices, especially the Arthrex TransFix might be tricky, because the manufacturer recommends the countersinking of the implant (see Fig. 57-10). Based on our own experience, we always schedule patients with a metallic TransFix for a two-staged procedure.

Tunnel Management

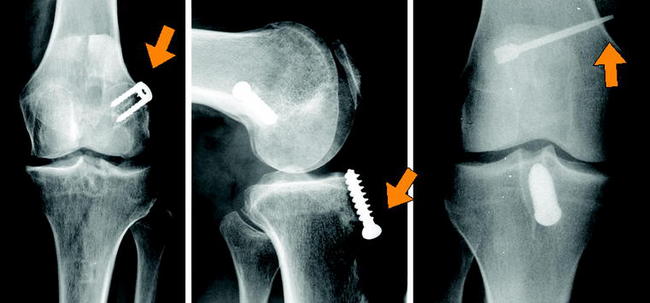

Tunnel Malplacement

According to the current literature the femoral tunnel should be drilled in the 10-o’clock position for right knees or in the 2-o’clock position for left knees.27–29 This means that a lateral femoral tunnel position should be achieved in order to control rotation as well as anterior displacement of the knee. A femoral tunnel drilled at the 12-o’clock position (“high-noon” or central cruciate) might be appropriate to control anterior translation but does not allow for rotational stabilization.30,31 Often in these cases a normal Lachman test with firm endpoint combined with a positive pivot-shift test can be found in the clinical examination.

Radiographically the tibial tunnel should be placed directly posterior to the intersection point of the Blumensaat line and the tibial joint line (lateral view in full knee extension) in order to avoid anterior impingement of the graft. Placement of the tibial tunnel too anteriorly might lead to an extension deficit due to notch impingement, which possibly results in long-term graft failure.14

Classification of Existing Tunnel Positions

Surgical Management

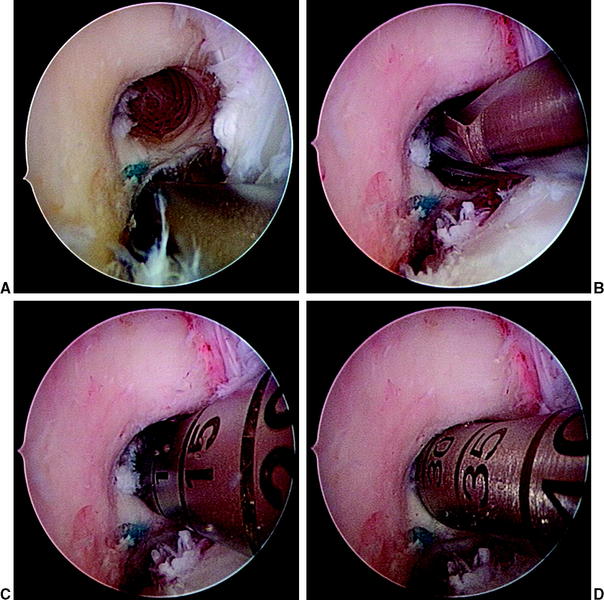

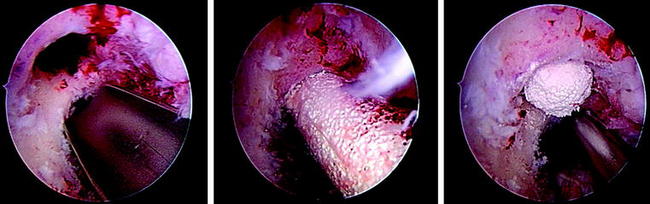

Correctly positioned tunnels measuring less than approximately 8 mm in diameter can be reused if primary reconstruction was performed with a soft tissue graft, depending on the desired type of fixation (isolated versus hybrid). In these cases, tunnel preparation includes removal of intratunnel soft tissue using a drill or a shaver followed by drilling or dilation of the re-created tunnel to the desired diameter. The important effect of this procedure is a débridement of the tunnel wall by removing sclerotic bone so that graft incorporation can proceed (Fig. 57-15).

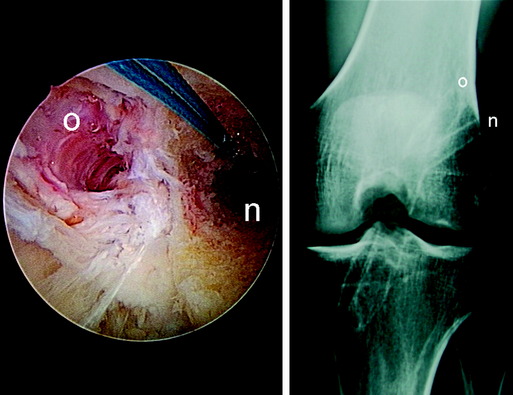

In cases of complete incorrect tunnel placement or complete bony replacement of the previous graft (e.g., BPTB), new tunnel preparation can be done as in primary ACL reconstruction. If an old and completely incorrect tunnel shows excessive enlargement, it should be filled with a cancellous bone plug or, as an alternative, with a biodegradable interference screw prior to graft fixation to prevent collapse between the old and new tunnels (Fig. 57-16).

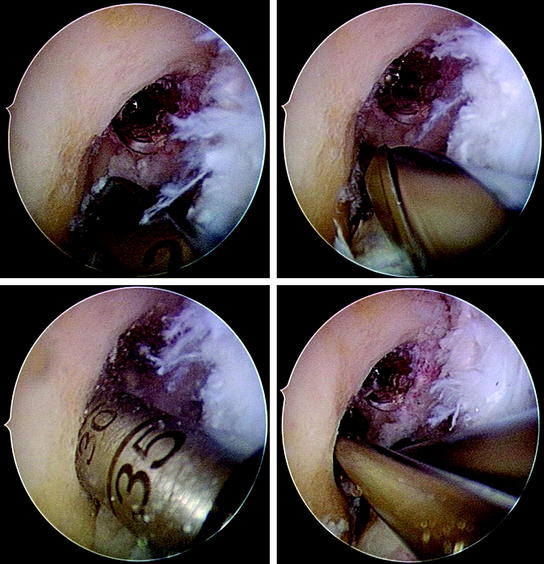

Surgically the most demanding cases are those with incompletely incorrectly placed tunnels. Drilling a correctly positioned tunnel in these cases might lead to huge bone defects. To achieve stable tunnel conditions, we suggest initially drilling a correctly placed tunnel with a diameter of only 4 to 5 mm and then using the serial dilation technique to the desired diameter. This procedure leads to a compaction of cancellous bone from the newly created tunnel into the old tunnel. In critical cases with very large bone defects or low bone density, a biodegradable interference screw or a cancellous bone plug can be placed into the old tunnel prior to dilation (Fig. 57-17). However, if there is any uncertainty, a two-staged procedure should be performed.

Tunnel direction must be verified in the coronal plane in addition to the tunnel entry position. Because many surgeons use a transtibial technique for femoral tunnel creation, the direction of a new tunnel drilled via the anteromedial portal diverges from the old tunnel, which finally improves graft fixation even if the tunnel entry site is enlarged (Fig. 57-18). Thus the anteromedial portal technique should be recommended routinely in all ACL revision procedures.

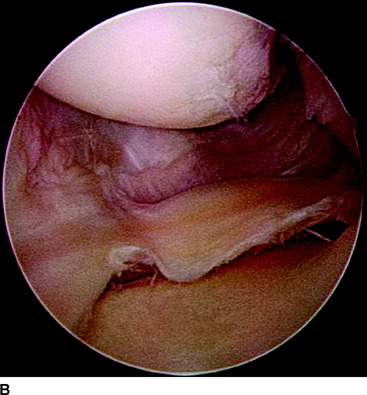

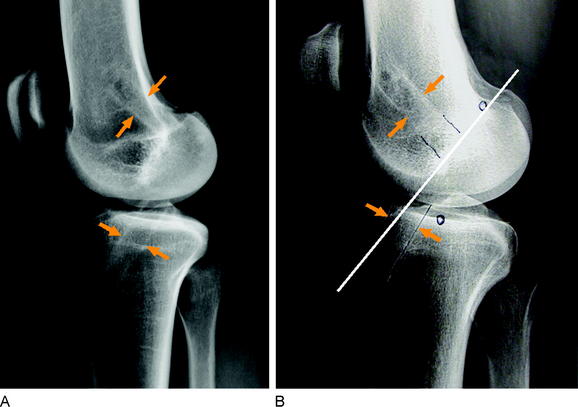

Tunnel Enlargement

Bone tunnel enlargement commonly occurs following an extracortical (nonanatomical) fixation technique combined with soft tissue grafts due to intratunnel graft motions or with BPTB grafts on the tibial site16,32 (windshield-wiper and bungee-cord effect) (Fig. 57-19). An additional biological factor that might lead to tunnel enlargement is inflow of synovial fluid between the tunnel wall and the graft during cyclical loading, which leads to high intratunnel pressures and the activation of osteoclasts by synovial cytokines. In these cases, radiographically the tunnel enlargement often appears pear–shaped below the joint line (see Fig. 57-19). The inflow of synovial fluid into the tunnel depends on the type of graft and its fixation.

Factors that inhibit synovial inflow are as follows:

In contrast, the inflow of synovial fluid is advanced by the following:

If a two-staged procedure is indicated, the first step includes autologous or allogenic cancellous bone or bone substitute filling followed by revision ACL reconstruction. On the femoral site, the impaction of a cylindrical iliac crest graft or a cylindrical synthetic filler (β-tricalcium phosphate [TCP]) can be nicely performed arthroscopically (Fig. 57-20). The use of bone chips on the femur might require special instruments if performed arthroscopically.16 On the tibial site one might use a single or two cylindrical plugs, which should be impacted. However, in most cases a tight filling with this technique is difficult. Thus we recommend using autologous bone chips, which are eventually mixed with synthetic materials (β-TCP) to tightly fill the old tunnel. In this case one should be careful not to compact bone chips into the joint cavity. We therefore recommend not to débride soft tissue from the tibial tunnel aperture site, which can later prevent bone chip access to the joint.

Graft Selection and Fixation

Graft Selection

Hamstring tendons have become increasingly popular in ACL surgery due to decreased donor site morbidity, improved cosmesis, and at least identical clinical outcome compared with autologous BPTB grafts if modern fixation techniques are used.33

Graft Fixation

The standard procedure in our institution for ACL revision reconstruction is a direct fixation technique by the use of biodegradable interference screws and hybrid fixation (Table 57-1) at both sites. General surgical principles of this technique, as well as possible intraoperative problems and their solution strategies, are described elsewhere in this text (see Chapter 46). The use of interference screws allows for an anatomical fixation at the level of the joint line, which has been shown to increase graft isometry34 and knee stability by reducing the graft length to its intraarticular portion, thus increasing construct stiffness.35,36 The use of interference fit fixation additionally reduces intratunnel graft motion, which is a common side effect of nonanatomical (extracortical) graft fixation.

| Femoral Hybrid Fixation |

|---|

| • Interference screw and EndoPearl suture button and interference screw |

| • Suture button and cancellous bone plug |

| • Transfixation and interference screw |

| • Transfixation and cancellous bone plug |

| Tibial Hybrid Fixation |

|---|

| • Interference screw and suture to bony bridge |

| • Interference screw and suture button |

| • Interference screw and staples |

| • Cancellous bone plug and suture button |

| • Cancellous bone plug and suture to bony bridge |

| • Cancellous bone plug and tying of sutures over screw |

An easy and secure method for tibial backup fixation is a suture of the linkage material over a bony bridge. To do so, a monocortical drill hole is created 2 cm distally of the tibial tunnel exit site. Then one strand of each attached suture is passed through the hole and tied over the created bony bridge37 (see Chapter 46).

For femoral hybrid fixation with interference screw fixation, we prefer the use of a biodegradable spherical device (EndoPearl, Linvatec, Largo, FL). The EndoPearl is sutured to the femoral end of the graft and achieves an internal locking between the graft and the tip of the interference screw. Thus it increases fixation strength, especially in cases of tunnel enlargement and low bone density (see Chapter 39).

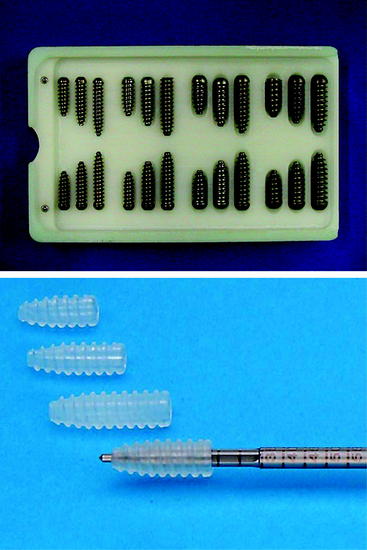

In cases with rather insecure tibial interference screw fixation, we favor the use of a suture button instead of the suture over a bony bridge. Manual rotation of the button tightens the linkage material, thus preventing graft slippage (see Chapter 46). Furthermore, in cases with impaired tibial bone quality, we suggest the use of oversized screws (diameter of 11–12 mm; Fig. 57-21) or the use of two screws (sandwich technique; Fig. 57-22) for tibial graft fixation.

1 Bach BRJr. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:4-29.

2 Wirth CJ, Peters G. The dilemma with multiply reoperated knee instabilities. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:148-159.

3 Wolf RS, Lemak LJ. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. J South Orthop Assoc. 2002;11:25-32.

4 Miller MD. Revision cruciate ligament surgery with retention of femoral interference screws. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:111-114.

5 Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Revision anterior cruciate surgery with use of bone-patellar tendon-bone autogenous grafts. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83A:1131-1143.

6 Allen CR, Giffin JR, Harner CD. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:79-98.

7 Brown CHJr, Carson EW. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Clin Sports Med. 1999;18:109-171.

8 Carson EW, Anisko EM, Restrepo C, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: etiology of failures and clinical results. J Knee Surg. 2004;17:127-132.

9 Fules PJ, Madhav RT, Goddard RK, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autografts with a polyester fixation device. Knee. 2003;10:335-340.

10 Johnson DL, Swenson TM, Irrgang JJ, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery: experience from Pittsburgh. Clin Orthop. 1996;325:100-109.

11 Kohn D, Rupp S. [Strategies for interventional revisions in failed anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction]. Chirurg. 2000;71:1055-1065.

12 Taggart TF, Kumar A, Bickerstaff DR. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a midterm patient assessment. Knee. 2004;11:29-36.

13 Thomas NP, Kankate R, Wandless F, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using a 2-stage technique with bone grafting of the tibial tunnel. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1701-1709.

14 Howell SM, Taylor MA. Failure of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament due to impingement by the intercondylar roof. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A:1044-1055.

15 Rosenberg TD, Paulos LE, Parker RD, et al. The forty-five-degree posteroanterior flexion weight-bearing radiograph of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:1479-1483.

16 Strobel M. Manual of arthroscopic surgery. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2001.

17 Fanelli GC, Orcutt DR, Edson CJ. The multiple-ligament injured knee: evaluation, treatment, and results. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:471-486.

18 Hillard-Sembell D, Daniel DM, Stone ML, et al. Combined injuries of the anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligaments of the knee. Effect of treatment on stability and function of the joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:169-176.

19 Christel P, Djian P. [Anterio-lateral extra-articular tenodesis of the knee using a short strip of fascia lata]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2002;88:508-513.

20 Ireland J. LeMaire procedure for anterior cruciate instability. Injury. 1999;30:151-152.

21 Lemaire M, Combelles F. [Plastic repair with fascia lata for old tears of the anterior cruciate ligament (author’s translation)]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1980;66:523-525.

22 Gollehon D, Torzilli P, Warren R. The role of the posterolateral and cruciate ligaments in the stability of the human knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69A:233-242.

23 Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Satoh H, et al. Posterolateral bundle reconstruction for rotatory instability after revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:546-549.

24 Veltri D, Warren R. Operative treatment of posterolateral instability of the knee. Clin Sports Med. 1994;13:615-627.

25 Strobel MJ, Weiler A, Schulz MS, et al. Fixed posterior subluxation in posterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees: diagnosis and treatment of a new clinical sign. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:32-38.

26 Weiler A, Jung T, Lubowicki A, et al. Management of posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction after previous isolated anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:164-169.

27 Hefzy M, Grood E, Noyes F. Factors affecting the region of most isometric femoral attachments. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:208-216.

28 Loh JC, Fukuda Y, Tsuda E, et al. Knee stability and graft function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Comparison between 11 o’clock and 10 o’clock femoral tunnel placement. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:297-304.

29 Sapega AA, Moyer RA, Schneck C, et al. Testing for isometry during reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Anatomical and biomechanical considerations. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:259-267.

30 Arnold MP, Kooloos J, van Kampen A. Single-incision technique misses the anatomical femoral anterior cruciate ligament insertion: a cadaver study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:194-199.

31 Musahl V, Plakseychuk A, Vanscyoc A, et al. Varying femoral tunnels between the anatomical footprint and isometric positions. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:712-718.

32 Höher J, Möller H, Fu F. Bone tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: fact or fiction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:231-240.

33 Wagner M, Kaab MJ, Schallock J, et al. Hamstring tendon versus patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using biodegradable interference fit fixation: a prospective matched-group analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1327-1336.

34 Morgan CD, Kalmam VR, Grawl DM. Isometry testing for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction revisited. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:647-659.

35 Ishibashi Y, Rudy T, Livesay G, et al. The effect of anterior cruciate ligament graft fixation site at the tibia on knee stability: evaluation using a robotic testing system. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:177-182.

36 Johnson D, Houle J, Almazan A. Comparison of intraoperative AP translation of two different modes of fixation of the grafts used in ACL reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:425.

37 Weiler A, Richter M, Schmidmaier G, et al. The EndoPearl device increases fixation strength and eliminates construct slippage of hamstring tendon grafts with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:353-359.