28 Reversers

Summary and Key Features

• Increasing popularity of soft tissue augmentation requires knowledge of reversal techniques

• Complications associated with fillers include nodules and contour irregularities, skin necrosis, allergic reaction, foreign-body response, and infection

• Biodegradable fillers are much more forgiving and more easily corrected

• Hyaluronidase can be considered a treatment ‘eraser’ for many complications arising from the injection of hyaluronic acid

• Non-inflammatory nodules can be managed conservatively

• Delayed inflammatory reactions may require more invasive techniques, particularly after complications due to non-biodegradable filling agents

Filler complications

Adverse effects following soft tissue augmentation are generally classified as early (up to 1 year) or delayed (appearing over 1 year after treatment) complications (Box 28.1). Delayed-onset reactions are almost always associated with non-biodegradable filling agents.

Hyaluronidase

Pearl 1

Hyaluronic acid fillers are the only truly reversible fillers with the use of hyaluronidase.

Hyaluronidase in cosmetic dermatology

In 2004, different reports by Soparkar and colleagues and Lambros detailed the use of hyaluronidase to dissolve unwanted side effects after augmentation with HA in the periocular region up to 5 years after initial HA injection. Since then, hyaluronidase has gained enormous popularity among cosmetic practitioners as an off-label ‘eraser’ for HA filling agents, with a reported ability to reverse bluish Tyndall discoloration, lumps and nodules due to overfilling or improper placement, foreign-body reactions, and injection necrosis (Box 28.2).

Several reports have documented the use of hyaluronidase to resolve the slightly bluish effect secondary to the Tyndall effect, caused by too-superficial injections of HA. Brody treated a 64-year-old woman who presented with visible, slightly blue masses beneath each eye 6 weeks after superficial HA injections in the periorbital area. Most of the material disappeared within 24 hours after 75 U of intradermal hyaluronidase; reinjection of the remaining small nodules dissolved the rest of the material within 5 days. In 2006, Hirsch and colleagues reported the case of a woman who developed a large blue ‘egg’ in the subdermal space at the right nasojugal fold 4 days after HA injection. Two injections of 75 U of hyaluronidase a few days apart led to complete resolution. Similar results were reported a year later by Hirsch and colleagues in a 48-year-old woman who received an overabundance of HA for the bilateral treatment of nasojugal folds and subsequently presented with two large, blue-tinted bulbous nodules under each eye. Hyaluronidase dissolved most of the material within 72 hours (Fig. 28.1)

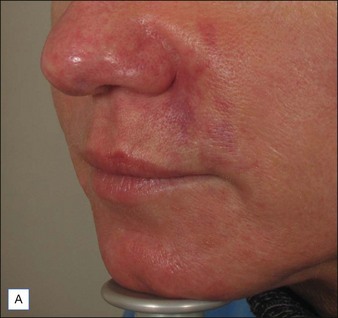

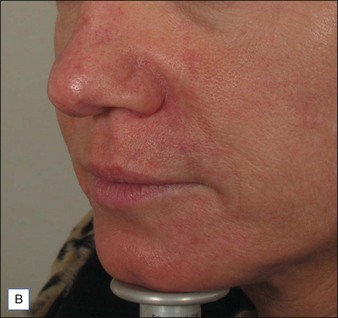

Hirsch and colleagues arrested tissue necrosis in a 44-year-old woman with multiple deep dermal injections of HA into the nasolabial folds whose nose began to ‘turn purple’ 6 hours later. Close examination revealed impending necrosis near the labial artery. After aspirin, topical nitroglycerin paste, and hot compresses for 8 hours failed to provide relief, 30 U hyaluronidase was injected to dissolve a suspected thrombus, with improvement noted at 8 hours and full resolution at 2 weeks (Fig. 28.2). A similar case was reported by Hirsch and colleagues in a 43-year-old woman who had undergone multiple rejuvenation sessions with collagen and HA in the past but experienced impending necrosis 48 hours after injection with HA for the augmentation of the nasolabial folds. Hyaluronidase brought immediate resolution of pain and a return to normal by day 13. Early intervention with the enzyme is recommended in cases of vascular compromise; Kim and colleagues demonstrated no benefit when used >24 hours after HA injection in rabbit ears.

Conservative ‘reversers’

In some cases, non-intervention – ’watchful waiting’ – or conservative management is the most appropriate course of action, particularly with the use of short-term biodegradable filling agents (Table 28.1). Non-inflammatory and non-painful lumps or nodules seen after treatment are usually due to improper injection techniques or misplacement / overcorrection of the filler material (Fig. 28.3). These cases will often resolve after a period of 1–2 weeks and can be combined with massage and possibly saline injection to help disperse the filling agent. Superficial injection of particulate fillers (calcium hydroxylapatite [CaHA] or polymethylmethacrylate [PMMA]) can produce ‘white bumps’ of visible material; these may be treated with saline injections and vigorous massage to ‘break up’ the deposits. In an animal study, Voigts and colleagues demonstrated that early intervention with fluid (sterile water or saline) combined with massage corrected any observed palpable accumulation of CaHA (nodules or irregular contours).

Table 28.1 Conservative versus semi-invasive and invasive ‘reversers’

| Conservative | Semi-invasive | Invasive |

|---|---|---|

Antibiotics, corticosteroids, and 5-fluorouracil

Red, painful nodules appearing from 2 weeks up to 1 year after treatment indicate infection and require immediate treatment with systemic antibiotics, incision and drainage, and hyaluronidase (Fig. 28.4). Clarithromycin 500 mg or minocycline 100 mg twice a day for 6 weeks will cover most early infections, although the length of treatment depends on the degree of infection and the duration of the implant.

Invasive reversal techniques

Injection of particulate fillers may result in the late appearance of visible nodules or bumps that are painless and non-inflammatory (Fig. 28.5). These may require ‘unroofing’ and evacuation with a needle tip or removal via superficial dermabrasion.

Late-onset infectious nodules appearing more than 1 year after treatment are sometimes attributed to the formation of a biofilm, which can be confirmed by biopsy and culture; infection will recur if the biofilm is not removed. Biofilms are usually associated with non-biodegradable fillers. Combination gels, such as PMMA or polyalkylimide, are most susceptible to complications from biofilms. Removal of the implant may sometimes be accomplished by expression through a small, sterile incision made over the site of augmentation (Fig. 28.6). Other cases require local anesthetic over the infected nodule, and extraction of the filling agent with an empty syringe and 16-gauge needle. However, needle aspiration of partially or completely non-resorbable polymers is rarely successful, particularly in cases of delayed presentation. Surgery is generally considered the last option after failure of more conservative approaches and should only be performed by experienced physicians. Fifty-two percent of patients in the IFS study experienced adverse effects such as scarring and asymmetry from surgical reversal.

Andre P, Fléchet ML. Angioedema after ovine hyaluronidase injection for treating hyaluronic acid overcorrection. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2008;7:136–138.

Brody HJ. Use of hyaluronidase in the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions or unwanted hyaluronic acid misplacement. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(8 pt 1):893–897.

Cassuto D, Marangoni O, De Santis G, et al. Advanced laser techniques for filler-induced complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(suppl 2):S1689–S1695.

Cohen JL. Understanding, avoiding, and managing dermal filler complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34(suppl 1):S92–S99.

Conejo-Mir JS, Sanz Guirado S, Angel Muñoz M. Adverse granulomatous reaction to Artecoll treated by intralesional 5-fluorouracil and triamcinolone injections. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32:1079–1081.

Glaich AS, Cohen JL, Goldberg LH. Injection necrosis of the glabella: protocol for prevention and treatment after use of dermal fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32:276–281.

Goldan O, Georgiou I, Grabov-Nardini G, et al. Early and late complications after a nonabsorbable hydrogel polymer injection: a series of 14 patients and novel management. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(suppl 2):S199–S206.

Hirsch RJ, Narurkar V, Carruthers J. Management of injected hyaluronic acid induced Tyndall effects. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2006;38:202–204.

Hirsch RJ, Brody HJ, Carruthers JD. Hyaluronidase in the office: a necessity for every dermasurgeon that injects hyaluronic acid. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2007;9:182–185.

Hirsch RJ, Cohen JL, Carruthers JD. Successful management of an unusual presentation of impending necrosis following a hyaluronic acid injection embolus and a proposed algorithm for management with hyaluronidase. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:357–360.

Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, et al. Injectable collagenase clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:968–979.

Kim DW, Yoon ES, Ji YH, et al. Vascular complications of hyaluronic acid fillers and the role of hyaluronidase in management. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2011;64(12):1590–1595.

Lambros V. The use of hyaluronidase to reverse the effects of hyaluronic acid filler. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;114:277.

Lee A, Grummer SE, Kriegel D, et al. Hyaluronidase. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:1071–1077.

Menon H, Thomas M, D’silva J. Low dose of hyaluronidase to treat over correction by HA filler – a case report. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2010;63:e416–417.

Narins RS, Coleman WP, 3rd., Glogau RG. Recommendations and treatment options for nodules and other filler complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(suppl 2):1667–1671.

Rzany B, Becker-Wegerich P, Bachmann F, et al. Hyaluronidase in the correction of hyaluronic acid-based fillers: a review and a recommendation for use. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2009;8:317–323.

Sclafani AP, Fagien S. Treatment of injectable soft tissue filler complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(suppl 2):1672–1680.

Soparkar CN, Patrinely JR. Managing inflammatory reaction to Restylane. Ophthalmic, Plastic, and Reconstructive Surgery. 2005;21:151–153.

Soparkar CN, Patrinely JR, Tschen J. Erasing Restylane. Ophthalmic, Plastic, and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;20:317–318.

Sperling B, Bachmann F, Hartmann V, et al. The current state of treatment of adverse reactions to injectable fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(suppl 3):1895–1904.

Vartanian AJ, Frankel AS, Rubin MG. Injected hyaluronidase reduces Restylane-mediated cutaneous augmentation. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2005;7:231–237.

Voigts R, DeVore DP, Grazer JM. Dispersion of calcium hydroxylapatite accumulations in the skin: animal studies and clinical practices. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:798–803.

Watt AJ, Curtin CM, Hentz VR. Collagenase injection as nonsurgical treatment of Dupuytren’s disease: 8-year follow-up. Journal of Hand Surgery. 2010;35:534–539.