Chapter 61 Revascularization Techniques in Pediatric Cerebrovascular Disorders

Moyamoya Syndrome

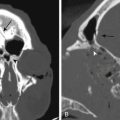

Moyamoya syndrome is an arteriopathy characterized by progressive stenosis of the distal internal carotid arteries as they enter the cranial vault.1,2 With narrowing of the internal carotids, cerebral blood flow is reduced, cerebral ischemia develops, and collateral blood vessels develop in the region of the carotid bifurcation, on the cortical surface, and from branches of the external carotid artery (ECA). This alternative blood supply—comprised of maximally dilated pre-existing arteries and growth of new vessels—provides circulation to the region formerly supplied by the internal carotids. Although usually limited to the anterior circulation, this process may involve the posterior circulation as well; including the basilar and posterior cerebral arteries. The appearance of this basal collateral network on angiography has been compared to a hazy cloud or puff of smoke: the disease defined by the Japanese word “moyamoya.” Because of the natural propensity in patients with moyamoya for collateral vessels to the brain to develop from branches of the external carotid and because these arteries and those on the surface of the brain are not involved by the moyamoya arteriopathy, most of the surgical revascularization techniques in this condition utilize the external carotid circulation as a donor source of new blood flow to the ischemic brain.

Surgical Treatment of Moyamoya

Historically, direct procedures have been used in adults, with immediate increase of blood flow to the ischemic brain cited as a major benefit of the procedure. Augmentation of cerebral blood flow usually does not occur for several weeks with indirect techniques. However, direct bypass is often technically difficult to perform in children because of the small size of donor and recipient vessels; making indirect techniques appealing. Nonetheless, direct operations have been successful in children as have indirect procedures in adults.3–5 Considerable debate exists regarding the relative merits and shortcomings of the two approaches; in fact, some centers advocate combinations of both approaches.5–7

Numerous indirect revascularization procedures have been described: encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis (EDAS) whereby the STA is dissected free over a course of several inches and then sutured to the cut edges of the opened dura; encephalomyosynangiosis (EMS) in which the temporalis muscle is dissected and placed onto the surface of the brain to encourage collateral vessel development; the combination of both, encephalo-myo-arterio-synangiosis (EMAS), a variant of EDAS in which the STA is sutured to the brain; pial synangiosis, described in detail below; and the drilling of multiple burr holes without vessel synangiosis.8–14 Dural inversion, carrying out a craniotomy, opening the dura, and turning the dural flaps inward over the surface of the brain has also been described as a revascularization technique.13 Cervical sympathectomy and omental transposition or omental pedicle grafting have also been described.2 We have found the technique of pial synangiosis particularly effective in the pediatric moyamoya population, and in a review of 143 patients treated with pial synangiosis, demonstrated marked reductions in stroke frequency following surgery.14 Regardless of the revascularization procedure utilized, the perioperative strategies for complication avoidance are relevant to all moyamoya patients, regardless of surgical technique employed.

Pial Synangiosis

We have recently published a specific perioperative protocol for patients with moyamoya15 (Table 61-1). This protocol has been adapted from our practice for all patients with moyamoya and highlights general strategies we have found useful in the surgical management of this condition.

Table 61-1 Perioperative Management Protocol Used at Our Institution for Patients with Moyamoya

| At 1 Day Before Surgery |

| Continue aspirin therapy (usually 81 mg once a day orally if <70 kg, 325 mg once a day orally if ≥70 kg). |

| Admit patient to hospital for overnight intravenous hydration (isotonic fluids 1.25–1.5 × maintenance). |

| At Induction of Anesthesia |

| Institute electroencephalographic monitoring. |

| Maintain normotension during induction; also normothermia (especially with smaller children), normocarbia (avoid hyperventilation to minimize cerebral vasoconstriction, pCO2 > 35 mm Hg), and normal pH. |

| Placement of additional intravenous lines, arterial line, Foley catheter, and pulse oximeter. |

| Place precordial Doppler to monitor for venous air emboli (relevant with thicker bone resulting from extramedullary hematopoiesis). |

| During Surgery |

| Maintain normotension, normocarbia, normal pH, adequate oxygenation, normothermia, and adequate hydration. |

| Electroencephalographic slowing may respond to incremental blood pressure increases or other maneuvers to improve cerebral blood flow. |

| Postoperatively |

| Avoid hyperventilation (relevant with crying in children); pain control is important. |

| Maintain aspirin therapy on postoperative day 1. |

| Maintain intravenous hydration at 1.25–1.5 × maintenance until child is fully recovered and drinking well (usually 48–72 hours). |

Revised from Smith ER, McClain CD, Heeney M, et al. Pial synangiosis in patients with moyamoya syndrome and sickle cell anemia: perioperative management and surgical outcome. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E10.

Preoperative Strategy and Imaging

Anesthetic Issues and Monitoring

We routinely supplement routine anesthetic monitoring with the use of intraoperative EEG. EEG is employed during surgery to identify focal slowing, indicative of compromised cerebral blood flow, so that immediate compensatory measures can be instituted by the operative team. EEG technicians must communicate changes in the EEG promptly to allow the team to respond immediately with appropriate titration of blood pressure, pCO2, and anesthetic agents.

Operative Technique and Setup

The specific equipment needed for the procedure includes:

• Hand-held “pencil” Doppler probes—necessary for mapping the STA.

• Powered drill (including footplate attachment)

• Microdissection instruments (including jeweler’s forceps, micro-tying instruments, Vanass ophthalmic scissors, and a disposable arachnoid knife)

• Colorado tip electrocautery (a very fine tip for the monopolar cautery)

Operative Approach

Vessel Dissection

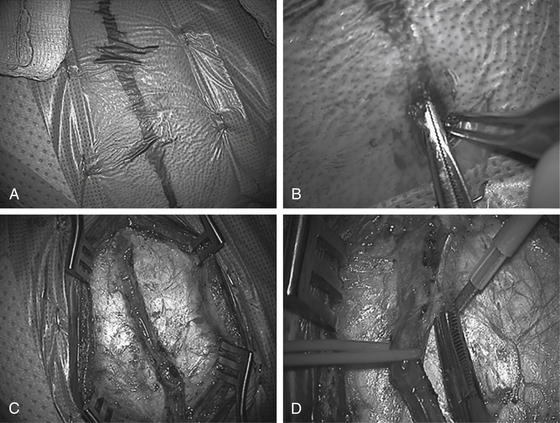

Using high magnification, a #15 blade is used to score the dermis at the distal end of the STA. A thin, curved pediatric hemostat and toothed Adson pickups are used by the surgeon (with suction and a second pickup by the assistant) to identify the STA under the skin. Using a repeated technique of subcutaneous dissection with the hemostat over the STA followed by elevation of the skin by the hemostat and an incision over the hemostat by the assistant, the STA is dissected along its length down to the root of the zygoma. Care must be taken to avoid tearing the vessel; particularly at tortuous bends or side branches. Irrigating bipolar (usually set at 25 with fine tips) is employed for hemostasis of small scalp vessels. A 0.05 × 3 cm Cottonoid is often useful to cover the exposed vessel to gently tamponade scalp bleeding as proximal dissection continues; electrocautery is used sparingly to control bleeding points along the incision line. A longer length of STA dissection is preferable (10 cm is optimal, although not always possible, especially in smaller children) (Fig. 61-1).

Following dissection of the STA branch, the “Colorado needle” electrocautery device (at low settings, usually one half to one third of the standard skin setting) is used in conjunction with the bipolar and microscissors to divide the galea and soft tissue on either side of the STA down to the temporalis fascia; leaving 1 to 2 mm of cuff on either side of the vessel. Two self-retaining retractors are then placed: one proximal and one distal. Dissection often terminates at the take-off of the frontal branch which should be preserved, if possible. However, if the bifurcation is high enough to prohibit mobilization of the STA then the frontal branch of the STA often must be divided. The preoperative arteriogram will indicate whether the frontal branch provides any significant intracerebral collaterals that can be relevant to the decision to potentially sacrifice the branch. Following the dissection of the vessel, a vessel loop is placed under the distal end of the STA and used to elevate the dissected portion of the vessel from the temporalis muscle. Monopolar electrocautery is then used to free up connective tissue around and beneath the vascular pedicle.

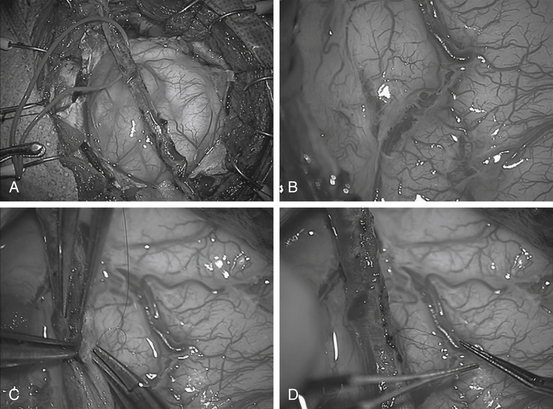

Craniotomy

Once the STA is freed, the microscope is removed and scalp flaps are developed using the electrocautery to minimize bleeding: creating a subgaleal dissection plane anteriorly and posteriorly. The temporalis is then divided into quadrants with the electrocautery. The muscle is reflected from the bone (with use of the electrocautery) and held back with multiple Lone Star retractors (fish hooks). Two burr holes are made; one inferior and one superior, in the bony exposure at the proximal and distal sites of the STA over the exposed bone. Following dural dissection with a #3 Penfield, the footplate is then used to turn the widest possible craniotomy flap. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the vessel. This is usually best performed by the assistant protecting the vessel with retractor (Fig. 61-2).

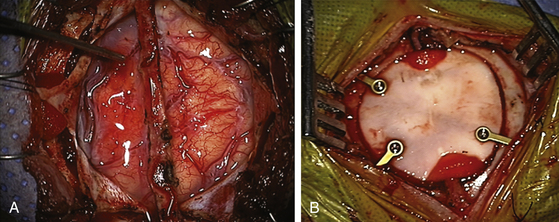

Closure

After synangiosis, the microscope is removed. The dural flaps are repositioned on the brain surface but not sutured. The entire craniotomy exposure is then covered with a large piece of Gelfoam soaked in saline. The burr holes on the bone flap are enlarged to facilitate entry and exit of the vessel (Fig. 61-3). The bone flap is replaced with small titanium plates (not over the burr holes) and the temporalis muscle is closed only vertically to prevent pressure on the entering and exiting STA. Galea is closed with interrupted 3-0 vicryls (4-0 in smaller patients), taking care to avoid injuring the STA. Finally, the skin is closed with a running 4-0 rapide or other absorbable suture. Occasionally, EEG slowing will be noted with replacement of the bone flap. These usually resolve by adjusting anesthetic management or occasionally by briefly lifting the bone flap, followed by replacement of the bone.

Complication Avoidance

The most significant postoperative complication in our series has been stroke, which in a series of 143 patients occurred at about 4% per operated hemisphere. Patients at the greatest risk appear to be those with neurologic instability around the time of surgery, those who have suffered a stroke within 1 month of the operation, or those with certain angiographic risk factors such as moyamoya disease in the posterior circulation. There have been two perioperative deaths related to ischemic stroke: one in a 5-year-old child operated on in the midst of a crescendo of strokes preoperatively and one in a 15-year-old boy with unusually fulminant disease with pre-existing basilar artery occlusion whose internal carotid artery—the sole supply of his posterior circulation—thrombosed following a unilateral operation. Other complications include four subdural hematomas requiring evacuation and two spinal fluid leaks.

Preoperative

As discussed in the preoperative section, careful management of moyamoya patients before they get to the OR can have a significant influence on complication avoidance. Patients, ideally, should be neurologically stable prior to surgery and at least 1 month out from any significant stroke. Patients must be medically optimized for surgery including prehydration, as described in our protocol (Table 61-1). Preoperative imaging is critical to planning vessel selection (the parietal branch of the STA may be small or absent, necessitating utilization of a frontal or retroauricular branch).

Follow-Up

Careful follow-up of patients with moyamoya is warranted to monitor for disease progression and for response to therapy.16,17 We routinely obtain MRI and MRA studies 6 months after surgery. Postoperative angiograms are usually obtained 12 months after surgery and typically demonstrate excellent MCA collateralization from both the donor STA and the meningeal arteries. A repeat MRI and MRA is done for comparison purposes and for a new baseline. For high-risk patients, MRI/A may be obtained in lieu of an angiogram if contrast from the angiogram presents a substantial risk to the kidneys. Generally, annual MRIs are obtained in all patients for 3 to 5 years after the initial 1-year angiogram and then spaced out subsequent to the 5-year time point. Particular attention must be paid to patients with unilateral moyamoya as the opposite side can progress in up to one third of patients, especially in children.18 Patients are maintained on lifelong ASA therapy.

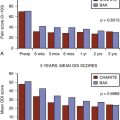

A review of 143 children with moyamoya syndrome treated with pial synangiosis had marked reductions in their stroke frequency after surgery especially after the first year postoperatively. In this group, 67% had strokes preoperatively and only 3.2% had strokes after at least 1 year of follow-up. The long-term results are excellent with a stroke rate of 4.3% (2 patients in 46) in patients with a minimum of 5 years of follow-up.19 This work supports the premise that pial synangiosis provides a significant protective effect against new strokes in this patient population.

Dauser R.C., Tuite G.F., McCluggage C.W. Dural inversion procedure for moyamoya disease. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:719-723.

Fukui M. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (“moyamoya” disease). Research Committee on Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis (Moyamoya Disease) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(suppl 2):S238-S240.

Fung L.W., Thompson D., Ganesan V. Revascularisation surgery for paediatric moyamoya: a review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:358-364.

Houkin K., Kamiyama H., Abe H., et al. Surgical therapy for adult moyamoya disease. Can surgical revascularization prevent the recurrence of intracerebral hemorrhage? Stroke. 1996;27:1342-1346.

Houkin K., Kuroda S., Nakayama N. Cerebral revascularization for moyamoya disease in children. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2001;12:575-584. ix

Ikezaki K. Rational approach to treatment of moyamoya disease in childhood. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:350-356.

Isono M., Ishii K., Kobayashi H., et al. Effects of indirect bypass surgery for occlusive cerebrovascular diseases in adults. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:644-647.

Kawaguchi S., Okuno S., Sakaki T. Effect of direct arterial bypass on the prevention of future stroke in patients with the hemorrhagic variety of moyamoya disease. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:397-401.

Matsushima T., Inoue T., Ikezaki K., et al. Multiple combined indirect procedure for the surgical treatment of children with moyamoya disease. A comparison with single indirect anastomosis with direct anastomosis. Neurosurgical Focus. 1998. 5:e4

Matsushima T., Inoue T., Katsuta T., et al. An indirect revascularization method in the surgical treatment of moyamoya disease—various kinds of indirect procedures and a multiple combined indirect procedure. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998;38(suppl):297-302.

Scott R.M., Smith E.R. Moyamoya disease and moyamoya syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1226-1237.

Scott R.M., Smith J.L., Roberstson R.L. Long-term outcome in children with moyamoya syndrome after cranial revascularization by pial synangiosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;100:142-149.

Scott R.M., Smith J.L., Robertson R.L., et al. Long-term outcome in children with moyamoya syndrome after cranial revascularization by pial synangiosis. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:142-149.

Sencer S., Poyanli A., Kiris T., et al. Recent experience with moyamoya disease in Turkey. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:569-572.

Smith E.R., McClain C.D., Heeney M., et al. Pial synangiosis in patients with moyamoya syndrome and sickle cell anemia: perioperative management and surgical outcome. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E10.

Smith E.R., Scott R.M. Surgical management of moyamoya syndrome. Skull Base. 2005;15:15-26.

Smith E.R., Scott R.M. Progression of disease in unilateral moyamoya syndrome. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E17.

Suzuki J., Takaku A. Cerebrovascular “moyamoya” disease: disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288-299.

Veeravagu A., Guzman R., Patil C.G., et al. Moyamoya disease in pediatric patients: outcomes of neurosurgical interventions. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E16.

1. Suzuki J., Takaku A. Cerebrovascular “moyamoya” disease: disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288-299.

2. Scott R.M., Smith E.R. Moyamoya disease and moyamoya syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1226-1237.

3. Isono M., Ishii K., Kobayashi H., et al. Effects of indirect bypass surgery for occlusive cerebrovascular diseases in adults. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:644-647.

4. Smith E.R., Scott R.M. Surgical management of moyamoya syndrome. Skull Base. 2005;15:15-26.

5. Veeravagu A., Guzman R., Patil C.G., et al. Moyamoya disease in pediatric patients: outcomes of neurosurgical interventions. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E16.

6. Ikezaki K. Rational approach to treatment of moyamoya disease in childhood. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:350-356.

7. Matsushima T., Inoue T., Ikezaki K., et al. Multiple combined indirect procedure for the surgical treatment of children with moyamoya disease. A comparison with single indirect anastomosis with direct anastomosis. Neurosurgical Focus. 1998. 5:e4

8. Matsushima T., Inoue T., Katsuta T., et al. An indirect revascularization method in the surgical treatment of moyamoya disease—various kinds of indirect procedures and a multiple combined indirect procedure. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998;38(suppl):297-302.

9. Kawaguchi S., Okuno S., Sakaki T. Effect of direct arterial bypass on the prevention of future stroke in patients with the hemorrhagic variety of moyamoya disease. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:397-401.

10. Houkin K., Kamiyama H., Abe H., et al. Surgical therapy for adult moyamoya disease. Can surgical revascularization prevent the recurrence of intracerebral hemorrhage? Stroke. 1996;27:1342-1346.

11. Sencer S., Poyanli A., Kiris T., et al. O. Recent experience with Moyamoya disease in Turkey. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:569-572.

12. Houkin K., Kuroda S., Nakayama N. Cerebral revascularization for moyamoya disease in children. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2001;12:575-584. ix

13. Dauser R.C., Tuite G.F., McCluggage C.W. Dural inversion procedure for moyamoya disease. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:719-723.

14. Scott R.M., Smith J.L., Roberstson R.L. Long-term outcome in children with moyamoya syndrome after cranial revascularization by pial synangiosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;100:142-149.

15. Smith E.R., McClain C.D., Heeney M., et al. Pial synangiosis in patients with moyamoya syndrome and sickle cell anemia: perioperative management and surgical outcome. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E10.

16. Fukui M. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (“moyamoya” disease). Research Committee on Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis (Moyamoya Disease) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(suppl 2):S238-S240.

17. Fung L.W., Thompson D., Ganesan V. Revascularisation surgery for paediatric moyamoya: a review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:358-364.

18. Smith E.R., Scott R.M. Progression of disease in unilateral moyamoya syndrome. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E17.

19. Scott R.M., Smith J.L., Robertson R.L., et al. Long-term outcome in children with moyamoya syndrome after cranial revascularization by pial synangiosis. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:142-149.