Chapter 52 Retropleural Approach to the Ventral Thoracic and Thoracolumbar Spine

Two of the most widely used approaches to the ventral thoracic and thoracolumbar spine are the transpleural thoracotomy and the lateral extracavitary approach.1,2 Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages. The major advantage of the ventrolateral transpleural thoracotomy is that it provides unparalleled exposure of the ventral vertebral column over several segments. Nevertheless, this exposure has several disadvantages. First, this approach is characterized by an extensive incision and soft tissue dissection that are necessitated by a deep operative field. Second, because with this approach the chest cavity is entered from the ventrolateral chest quadrant, significant retraction of the unprotected lung is required. Finally, identification and decompression of the ventral spinal canal are also problematic, because the rib head partially obscures the spinal canal and the epidural veins are difficult to control via this trajectory. The aforementioned factors can create a less secure operative environment, increase surgical morbidity, and hinder the attainment of the surgical objective(s).

A retropleural thoracotomy, ideally, is more suited for a ventral exposure of the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine.3–7 Similar to the situation in ventrolateral thoracotomy, the line of vision provided with a retropleural thoracotomy is ventral to the ventral aspect of the spinal canal, but because the chest cavity is entered more dorsally, there is a significantly shorter distance to the ventral vertebral column and canal. The extrapleural nature of the dissection allows safer and more secure lung retraction and avoids postoperative tube thoracostomy placement. This approach allows for earlier identification and entry into the lateral spinal canal, via a resected pedicle. It greatly facilitates ventral spinal canal decompression through the disc space and vertebral bodies. Unlike the lateral extracavitary approach, however, mobilization or sacrifice of the foraminal neurovascular structures is avoided. Thus, retropleural thoracotomy represents a hybrid surgical approach, incorporating the advantages of both standard transpleural ventrolateral and dorsolateral extrapleural approaches while avoiding their limitations.

Surgical Technique

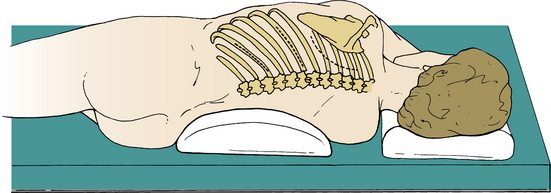

After appropriate arterial and venous line access has been established, induction and intubation are performed. A double-lumen tube is used for lesions above the T6 vertebral level. An epidural catheter may be placed after intubation or at the conclusion of the procedure for postoperative pain management. A broad-spectrum antibiotic is usually administered 30 minutes before the skin incision, and this may be continued for two postoperative doses. The patient is carefully turned into a lateral position on a beanbag chair, with a small, soft roll under the dependent axilla. The upper arm is supported on a pillow or sling. The lower leg is slightly flexed at the hip and knee to help secure the position. All bony prominences and subcutaneously coursing nerve trunks must be well padded. The ulnar nerve at the elbow and the peroneal nerve at the fibular neck are particularly vulnerable areas. Thoracolumbar lesions should be centered over the kidney break. The skin incision is planned according to the level of exposure. For midthoracic lesions (T5-9), a 14-cm skin incision should extend from a point 4 cm off the dorsal midline to the dorsal axillary line. Extension of the incision toward the midaxillary line expands ventral access and may be required in some cases (Fig. 52-1, center incision). A curved incision that parallels the medial and inferior scapular border is used for upper (T3-4) thoracic lesions (see Fig. 52-1, right incision). For thoracolumbar exposure (T10-L2), the incision should parallel the rib one spinal segment above the pathologic level because of the more caudal inclination of the proximal portion of the lowest ribs (see Fig. 52-1, left incision). Therefore, whereas the approach to a T7-8 disc is exposed through the T8 rib bed, a T12 lesion is approached through the bed of the T11 rib.

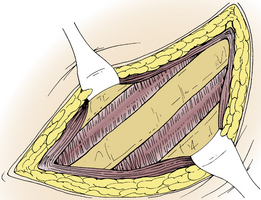

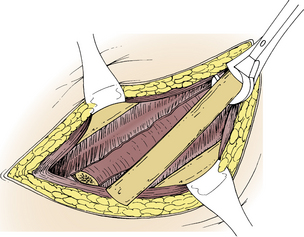

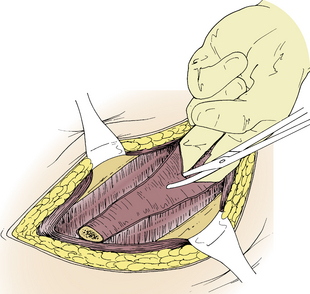

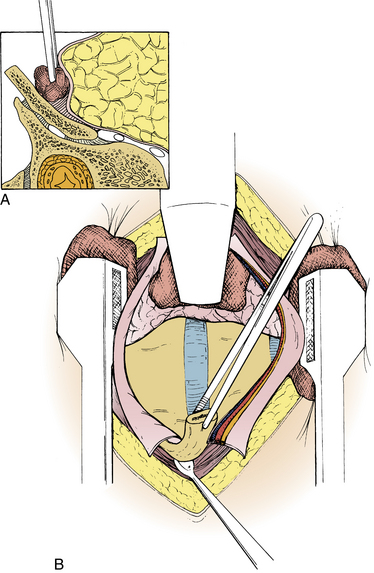

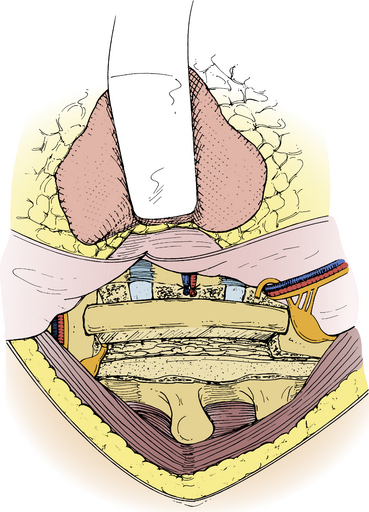

The skin incision is carried down to the rib (Fig. 52-2). A 10- to 12-cm rib segment, extending from the costotransverse ligament to the dorsal axillary line, is subperiosteally exposed and removed with rib shears (Fig. 52-3). The exposed bone surfaces are waxed. Note that the proximal 4 cm of the rib, extending from the costotransverse articulation to the rib head, has yet to be removed. The bed of the resected rib is now inspected. Muscle fibers of an inconstant subcostal muscle may be seen. At thoracic levels above T10, the endothoracic fascia will be identified in the rib bed. The endothoracic fascia is analogous to the transversalis fascia of the abdominal cavity.8 Both types of fascia line the walls of their respective visceral cavities and are reflected onto the surface of the diaphragm. The endothoracic fascia is tightly applied to or is continuous with the inner periosteum of the rib and vertebral bodies. The parietal pleura maintains its attachment to the chest wall through a surface tension seal with the inner surface of the endothoracic fascia. The intercostal vessels, nerves, and sympathetic chain are contained within the endothoracic fascia. Although only a potential (subendothoracic) space exists between the endothoracic fascia and the parietal pleura, a small amount of fluid and loose adipose tissue is occasionally identified, particularly dorsally near the rib head and vertebral bodies. Because the endothoracic fascia is continuous with the inner periosteum of the rib, it may be inadvertently torn during rib dissection and removal. This is common in older patients. If the endothoracic fascia is intact, it should be incised in line with the rib bed (Fig. 52-4). The underlying parietal pleura is bluntly and widely separated from the endothoracic fascia, either manually or with a Kittner (peanut) clamp (Fig. 52-5). The endothoracic fascia incision is continued dorsally to the margin of the cut surface of the remaining proximal rib. Blunt dissection of the pleura off the proximal rib head extends dorsally to expose the vertebral bodies and disc space. When the ventral convex border of the vertebral body has been exposed, a self-retaining, table-mounted retractor maintains exposure of the vertebral column (Fig. 52-6).

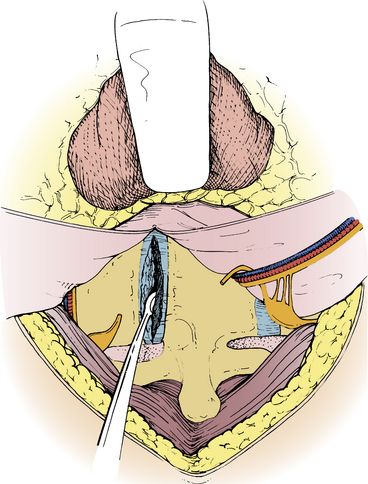

The endothoracic fascia incision is continued dorsally over the remaining proximal rib segment and onto the vertebral body with electrocautery. This divides the sympathetic chain that descends within the endothoracic fascia, just ventral to the rib head insertion on the surface of the vertebral column. The musculoligamentous attachments, including the costotransverse and stellate ligaments, are detached from the rib head segment, which is then removed. Removal of the rib head is critical because it allows identification of the pedicle (through which the lateral spinal canal entry will subsequently be accessed). For thoracic disc removal, the incised endothoracic fascia and vertebral body periosteum are elevated in either direction from the disc space to the midvertebral body. The intercostal vessels, which run transversely at the midvertebral level, are preserved within the reflected tissue. The margins of the pedicle are defined with angled curettes and nerve hooks. The pedicle is resected with a high-speed drill or Kerrison rongeurs. Removal of the pedicle provides lateral spinal canal identification and entrance. This lateral canal entrance, unlike the lateral extracavitary approach, avoids a bloody foraminal dissection as well as possible nerve root and radiculomedullary artery injury.

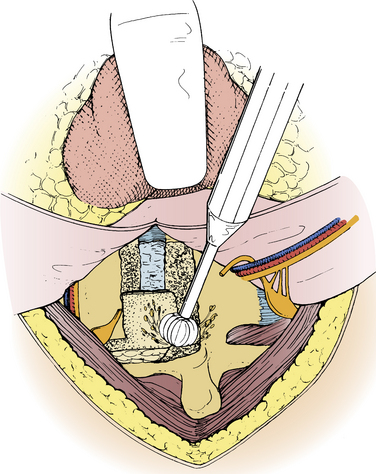

The lateral disc anulus fibrosus is sharply incised. The disc is evacuated with curettes and rongeurs. The adjacent end-plate and vertebral body margins are removed with a high-speed drill. The width and depth of the disc and adjacent vertebral body dissection must be adequate to ensure ventral spinal canal exposure and decompression. The depth should extend 3 to 3.5 cm from the lateral body vertebral margin to reach the contralateral pedicle. The width should extend about 1 cm on either side of the disc into the adjacent vertebral bodies (wider for larger calcified discs that have migrated, usually caudally, behind the vertebral body). The dissection is continued dorsally toward the spinal canal with disc curettage and a high-speed drill (Fig. 52-7). Spinal canal identification through the disc space and adjacent vertebral bodies is readily achieved because of the previously exposed lateral spinal canal entrance through the resected pedicle bed. When the dissection is carried back to the dorsal cortical margin and dorsal anulus fibrosus, a sharp, reverse-angle curette is passed through the lateral spinal canal entrance to displace these structures away from the spinal canal and into the bed of the resected disc and adjacent vertebral bodies. This maneuver may precipitate epidural bleeding that can be effectively managed with bipolar cautery forceps, introduced through the lateral spinal canal margin or with small pieces of Surgicel. As in the ventral cervical region, a thin dorsal layer of posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) often remains after resection of the thicker ventral portion of the PLL (which is firmly attached to the dorsal disc anulus). Many calcified thoracic disc fragments are suspended within this thin dorsal PLL laver and are not located intradurally as often as the literature suggests. The ventral spinal canal should be probed with a microdissector and nerve hook for identification and delivery of these fragments that are suspended within this layer of ligament. The dura mater should be clearly identified before the decompression is considered complete. After adequate spinal canal decompression has been achieved, an interbody autologous rib graft is placed, although its efficacy after routine discectomy has as yet to be established (Fig. 52-8).

FIGURE 52-7 After disc curettage, the adjacent vertebral end plates and pedicle are removed with a high-speed drill.

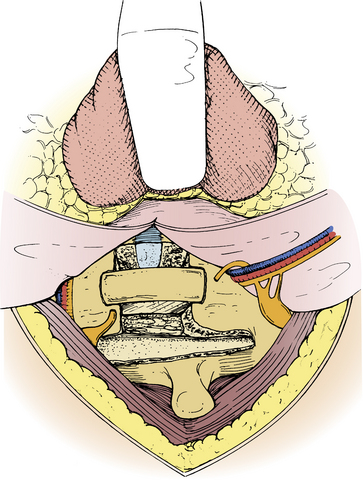

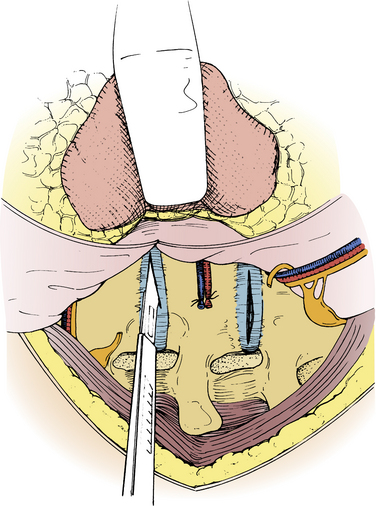

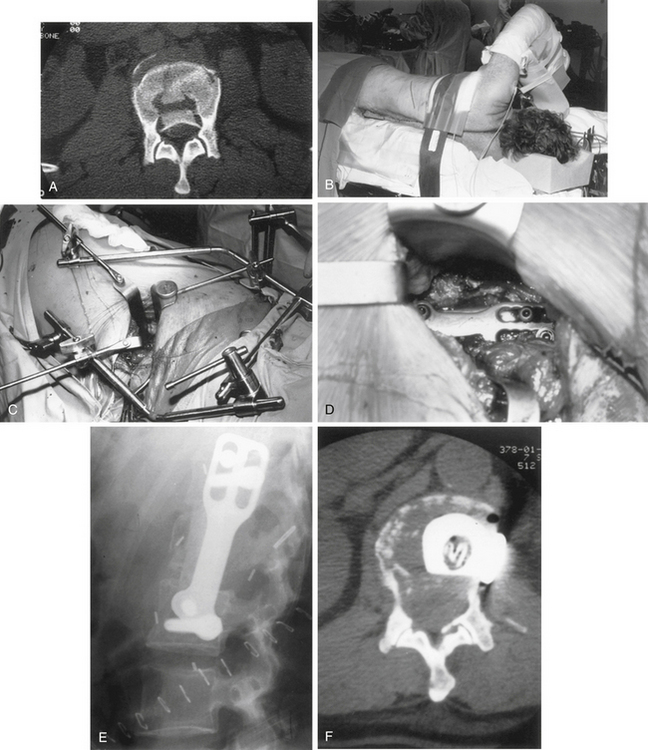

A more extensive dissection is required for vertebral corpectomy, particularly if stabilization with a lateral metallic implant is planned. For a T8 corpectomy, after the initial exposure through the T8 rib bed, the T8 and T9 rib heads are removed to expose the T7-8 and T8-9 disc spaces. The segmental artery and vein at the T8 midvertebral body level are individually ligated and divided as ventrally as possible. After resection of the pedicle of the vertebral body to be resected, the discs above and below the vertebral body are incised and evacuated (Fig. 52-9). Rongeurs and a high-speed drill are used to complete the corpectomy. Appropriate stabilization is then performed (Fig. 52-10). If a lateral implant is planned, the lateral aspects of the instrumented segments must be well exposed. This includes subperiosteal reflection of the endothoracic fascia and suture ligation and division of the segmental vessels at the midvertebral body level. The rostral margin of the rib of the rostral instrumented vertebrae may also have to be removed to achieve adequate exposure for plate placement.

The retropleural approach is modified at the thoracolumbar junction (T10-L2), because of the caudal rib angulation and diaphragm attachments (Fig. 52-11). At these levels, the approach is through the rib, one level above the pathologic segment. When the initial rib segment is removed, the diaphragm, rather than the endothoracic fascia, remains in the bed of the rib at the lowest three rib levels. A Cobb elevator is used to detach the dorsal diaphragm margins from their attachment to the inner surfaces of the rib origins. This immediately unites the retropleural and retroperitoneal compartments. The dissection continues dorsally to elevate the diaphragm from the dorsal abdominal wall attachments to the quadratus lumborum muscle (lateral arcuate ligament), the psoas muscle (medial arcuate ligament), and the vertebral body (crus). The exposure is maintained with table-mounted retractors. Elevation of the psoas muscle with electrocautery is required at the L1 and L2 levels. Decompression and stabilization are then performed by using the previously described techniques and principles. After decompression and stabilization, the diaphragm is reattached to the psoas and quadratus muscles with suture.

Follow-Up

In the author’s experience, the morbidity and complications are less than were seen in previous experience with the standard transpleural ventrolateral thoracotomy. Postoperative pain is similar to that encountered with dorsolateral approaches, which suggests that the pleural incision accounts for much of the postoperative intercostal neuralgia that has occurred in fewer than 10% of patients. In some patients, postoperative intercostal pain and dysesthesias eventually lessened and evolved into a mildly annoying numbness or hypersensitivity. For lower thoracic and thoracolumbar approaches (T7-L1), abdominal wall outpouching (i.e., pseudohernia) has also occurred, particularly in middle-aged men.

Angevine P.D., McCormick P.C. Retropleural thoracotomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10:1-5.

Angevine P.D., Parsa A.T., Schwartz T.H., McCormick P.C. Ventral approach: extrapleural thoracotomy. Tech Neurosurg. 2003;8(2):122-129.

Bohlman H.H., Zdeblick T.A. Anterior excision of herniated thoracic discs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1988;20:1038-1047.

Louis R. Surgery of the spine. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1983. pp 228–231

McCormick P.C. The lateral extracavitary approach to the thoracic and lumbar spine. In: Holtzman R.N.N., McCormick P.C., Farcy J.P.C., editors. Spinal instability. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1993:335-348.

McCormick P.C. Retropleural approach to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:908-914.

1. Bohlman H.H., Zdeblick T.A. Anterior excision of herniated thoracic discs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1988;20:1038-1047.

2. McCormick P.C. The lateral extracavitary approach to the thoracic and lumbar spine. In: Holtzman R.N.N., McCormick P.C., Farcy J.P.C., editors. Spinal instability. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1993:335-348.

3. Angevine P.D., McCormick P.C. Retropleural thoracotomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10:1-5.

4. Angevine P.D., Parsa A.T., Schwartz T.H., McCormick P.C. Ventral approach: extrapleural thoracotomy. Techn Neurosurg. 2003;8(2):122-129.

5. Louis R. Surgery of the spine. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1983. pp 228–231

6. McCormick P.C. Retropleural approach to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:908-914.

7. Otani K., Yoshida M., Fujii E., et al. Thoracic disc herniation: surgical treatment in 23 patients. Spine. 1988;13:1262-1267.

8. Hollinshead W.H. Textbook of anatomy, ed 3. Hagerstown, MD: Harper & Row; 1974. pp 496–501