24 Retrobulbar (Peribulbar) Block

Placement

Anatomy

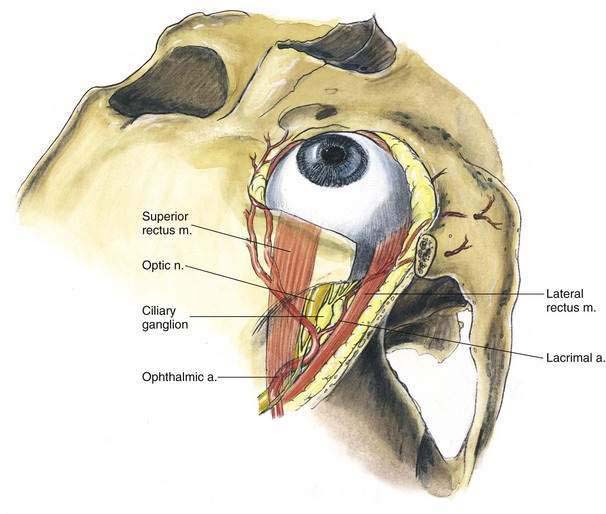

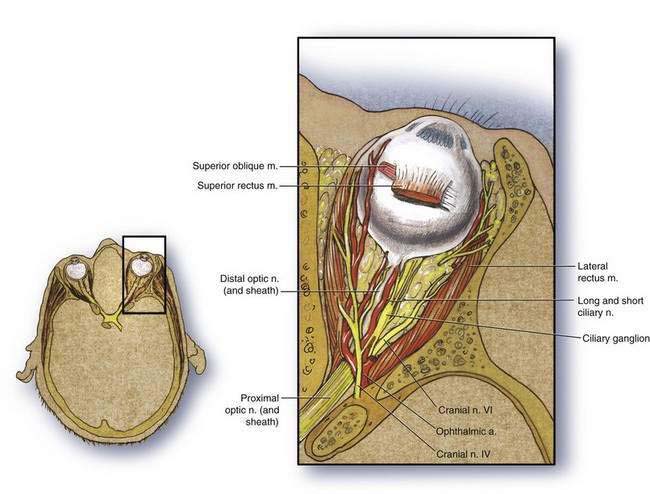

Sensation to the eye is provided by the ophthalmic nerve through the long and short posterior ciliary nerves. Autonomic innervation is provided by the same nerves, and sympathetic fibers traveling with the arteries and parasympathetic fibers carried by the inferior branch of the oculomotor nerve provide additional autonomic innervation. Because the innervation of the orbicularis oculi muscle is through the facial nerve, blockade of these fibers is required to ensure a quiet eye during ophthalmic operations. The ciliary ganglion, measuring approximately 2 to 3 mm in length, lies deep in the orbit just lateral to the optic nerve and medial to the lateral rectus muscle. From this ganglion, the long and short ciliary nerves extend forward in the orbit. Immediately posterior to the ciliary ganglion, the ophthalmic artery can be found at the lateral side of the optic nerve as it crosses superior to it and passes forward medially (Fig. 24-1).

Position

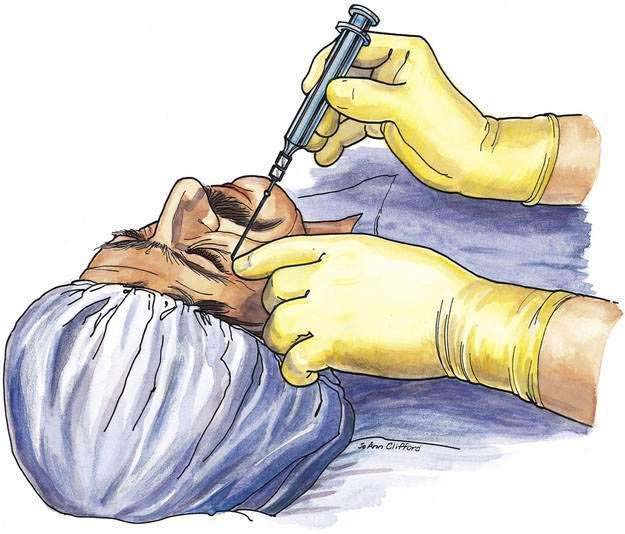

Patients are placed in the supine position and are instructed to maintain their primary gaze directly ahead, not “up and in,” as in earlier recommendations. With the globe in primary gaze, the optic nerve position minimizes potential intraneural injection. The anesthesiologist is positioned for the injection as illustrated in Figure 24-2.

Needle Puncture

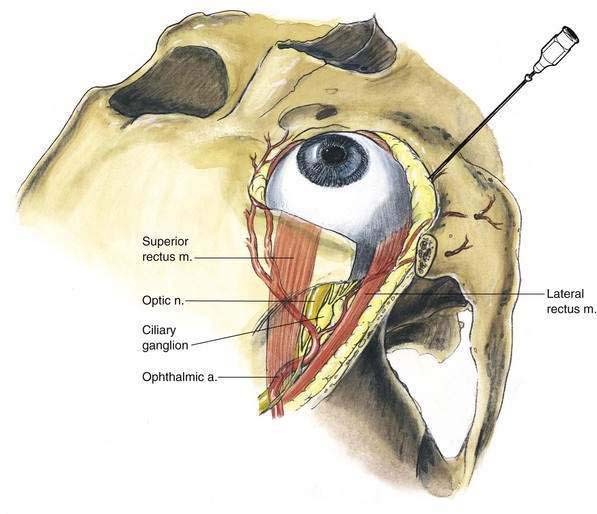

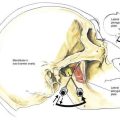

While the patient’s gaze is directed cephalad and opposite to the site of injection, a 27-gauge, 31-mm, sharp-beveled needle is inserted at the inferolateral border of the bony orbit and directed toward the apex of the orbit, as illustrated in Figure 24-3. The needle should be oriented so that the bevel opening faces toward the globe. A “pop” may be appreciated as the needle tip traverses the bulbar fascia and enters the orbital muscle cone. Before 2 to 4 mL of local anesthetic is injected, careful needle aspiration should be carried out. After retrobulbar block, 5 to 10 minutes should be allowed to pass before the operation is started. This helps to avoid operating on patients who develop retrobulbar hematomas. During these 5 to 10 minutes, the anesthesiologist can apply gentle pressure to the globe, principally to facilitate lowering the intraocular pressure. If a peribulbar technique is chosen, needle insertion begins like that used for retrobulbar (inferotemporal) injection; however, the operator inserts the needle parallel and lateral to the lateral rectus muscle and bulbar fascia rather than making an effort to puncture it. Many practitioners also now suggest making a second injection of 3 to 5 mL for a peribulbar block either in the superomedial orbit or at the extreme medial side of the palpebral fissure. To complete the local block for ocular surgery, the orbicularis oculi muscle must be blocked to produce an immobile eye. This is carried out by blocking the facial nerve fibers that innervate the muscle.

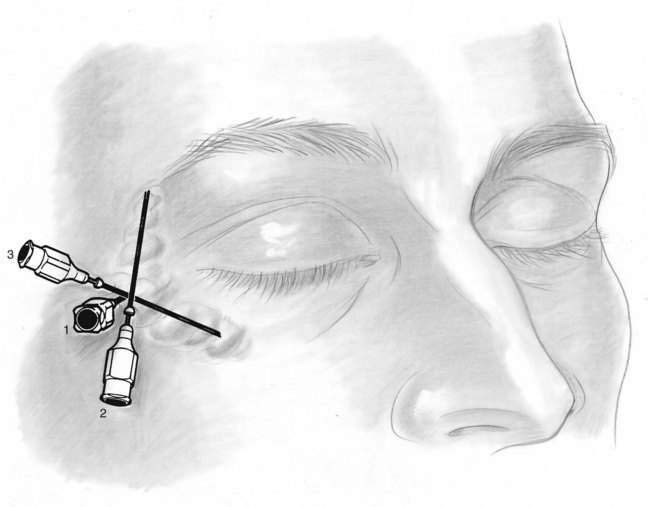

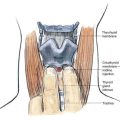

There are many ways of performing blocks of these facial nerve fibers, and the method illustrated in Figure 24-4 is the example of Van Lint. In this block, a 25-gauge, 4-cm needle is inserted at needle position 1 until the lower inferolateral orbital rim is reached. While the needle tip contacts bony surface, 1 mL of local anesthetic is injected. Through this skin wheal, the needle is repositioned along the lateral and inferior margins of the orbit (needle positions 2 and 3), and 2 to 3 mL of local anesthetic is injected along each needle path.

Potential Problems

The most common complication with retrobulbar block is hematoma formation. This can be minimized by using a needle shorter than 31 mm. Hematoma formation is more likely if a longer needle is used and the needle tip rests in the vicinity of the ophthalmic artery as it crosses the optic nerve. Hematoma can also be minimized by using a peribulbar approach. Other complications that can accompany retrobulbar block include local anesthetic toxicity, development of the oculocardiac reflex, and cases of sudden apnea and obtundation after retrobulbar injection. The latter two results are probably related to injection within the optic nerve sheath, resulting in unexpected spinal anesthesia, or intravascular injection affecting the respiratory centers in the midbrain, as illustrated in Figure 24-5.