Chapter 496 Retinoblastoma

Epidemiology

According to Knudson’s “two-hit” model of oncogenesis, two mutational events are required for retinoblastoma tumor development (Chapter 486). In the hereditary form of retinoblastoma, the first mutation in the RB1 gene is inherited through germinal cells and a second mutation occurs subsequently in somatic retinal cells. Second mutations that lead to retinoblastoma often result in the loss of the normal allele and concomitant loss of heterozygosity. Most children with hereditary retinoblastoma have spontaneous new germinal mutations, and both parents have wild-type retinoblastoma genes. In the sporadic form of retinoblastoma, the two mutations occur in somatic retinal cells. Heterozygous carriers of oncogenic RB1 mutations demonstrate variable phenotypic expression.

Clinical Manifestations

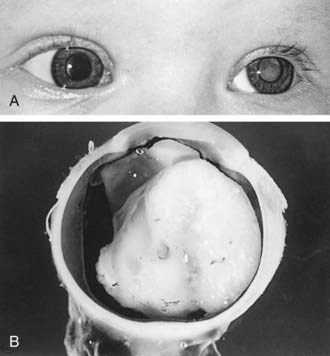

Retinoblastoma classically presents with leukocoria, a white pupillary reflex (Fig. 496-1), which often is first noticed when a red reflex is not present at a routine newborn or well child examination or in a flash photograph of the child. Strabismus often is an initial presenting complaint. Orbital inflammation, hyphema, and pupil irregularity can occur with advancing disease. Pain can occur if secondary glaucoma is present. Only about 10% of retinoblastoma cases are detected by routine ophthalmologic screening in the context of a positive family history.

Abramson DH, Schefler AC. Update on retinoblastoma. Retina. 2004;24:828-848.

Classon M, Harlow E. The retinoblastoma tumour suppressor in development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:910-917.

Kleinerman R, Tucker MA, Tarone RF, et al. Risk of new cancers after radiotherapy in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma: an extended follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2272-2279.

Lohman DR, Gallie BL. Retinoblastoma: Revisiting the model prototype of inherited cancer. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;129:23-28.

MacCarthy A, Bayne AM, Draper GJ, et al. Non-ocular tumours following retinoblastoma in Great Britain 1951 to 2004. Br J Opthalmol. 2009;93:1159-1162.

Richter S, Vandezande K, Chen N, et al. Sensitive and efficient detection of RB1 gene mutations enhances care of families with retinoblastoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:253-269.

Rodriguez-Galindo C, Chantada G, Wilson MW, et al. Treatment of retinoblastoma: current status and future perspectives. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2007;9:294-307.

Woo KI, Harbour W. Review of 676 second primary tumors in patients with retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(7):865-870.