Chapter 37 Restless Legs Syndrome Morbidity: Sleep and Quality of Life

Aside from the increased risk of death for patients with both restless legs syndrome (RLS) and end-stage renal disease (see Chapter 25), RLS has no known impact on mortality. But the symptoms associated with the disorder adversely affect several key aspects of daily life. We often assume that we already know the impact of these symptoms on functioning and therefore focus mostly on describing and evaluating the symptoms rather than looking at their impact on the patient’s life. Indeed, this approach has been taken for RLS, and even as late as 2003 there had been very few published studies on the morbidity of RLS. This turns out to be particularly regrettable for RLS. For the morbidity may provide an important, if not the primary, justification for treatment of the disorder. The rationale for treatment then lies not merely with reducing the symptoms but also with reducing the impact they have on the patient’s life.

Morbidity From Sleep Disturbance of Restless Legs Syndrome

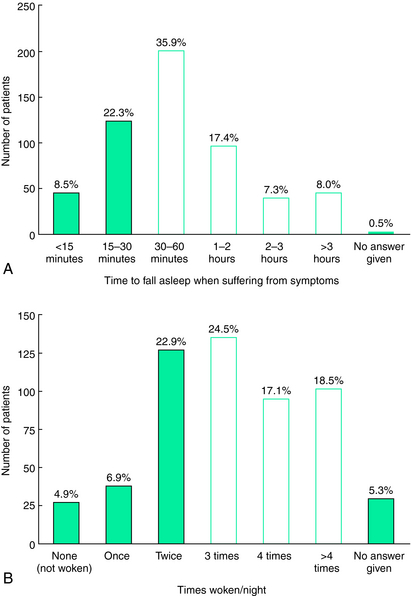

RLS classification as a sleep-related disorder1 emphasizes the sleep disturbance characterizing the disorder. By definition, rest provokes RLS symptoms and it can be seen as a disorder of that quiet drowsy state of waking (the predormitum) that precedes sleep but may occur at other times during the day. RLS will therefore generally disrupt sleep, and indeed, the population-based surveys indicate more than 75% of those with at least moderate RLS symptoms complain of significant sleep disturbance caused by their RLS.2 It appears that some who have very mild RLS do not have any sleep complaint. In such cases, the patient appears to fall asleep fast enough to avoid developing significant symptoms while lying in bed; the longer periods of sitting in the evening, however, cause considerable distress. Most RLS patients, though, complain of interrupted sleep, insufficient hours of sleep, and difficulty falling and staying asleep. Curiously, only a minority complain of daytime sleepiness.2 Figure 37-1 shows the range of RLS effects on sleep onset and sleep awakenings for those with moderate to severe RLS symptoms. These have been confirmed by polysomnographic studies of RLS patients3 and by reports from clinical trial populations showing decreased total sleep times, decreased sleep adequacy, and increased sleep disturbance, which are largely improved by treatment with the dopamine agonist ropinirole.4,5 Sleep efficiency for the more severely affected RLS patient drops below 60% with less than 5 hours a sleep a night for most nights,6 producing what is probably the most extreme chronic sleep loss of any sleep-related disorder; yet, there have been few studies evaluating the effect of this sleep loss.

Profound daytime sleepiness should develop with this level of sleep loss, but surprisingly RLS patients generally do not report falling asleep in the daytime at inappropriate times (e.g., sitting in a car at a red light, talking on the telephone). Thus, the question arises—Aside from the discomfort from not sleeping, do RLS patients have any adverse effects from the sleep loss? That is, do RLS patients show changes in mood, cognition, attention, or pain perception generally associated with significant sleep loss? Unfortunately, to date, this has hardly been studied at all. Saletu and colleagues7 found no excessive sleepiness or vigilance decrement for untreated RLS patients compared with control subjects. Pearson and colleagues,8 however, did find that untreated RLS patients had decreased cognitive performance in the morning on verbal fluency and trail making tests consistent with the prefrontal cognitive effects shown for one night’s of total sleep deprivation.9 Aside from these studies, we know very little about the effects of the sleep disturbance in RLS. It looks as if it produces an awake, but possibly fatigued, individual with some disturbance of prefrontal cognitive functioning, a type of dysfunction also shown with attention deficit disorder.10

Quality of Life Measures Used in Restless Legs Syndrome

Three basic types of QoL measurements have been developed: general QoL assessments, disease-specific QoL measures, and judgments or recording of critical life-activities or events. The general QoL assessments usually focus on providing a broad-based assessment of health-related impacts on QoL. Several instruments have been developed to provide this type of QoL assessment, including the Nottingham Health Profile, the Sickness Impact Profile, and the 36-item Short-form Health Survey (SF-36). The most commonly used and best standardized is the Medical Outcomes Study11 SF-36,12,13 which has been shown to have very good psychometric properties when used in a patient population.14 The SF-36 also comes in two shortened forms: the SF-1215 and the SF-8.16 The SF-36 provides scores in eight dimensions and a summary score for four dimensions covering physical health (physical functioning, role physical, pain, and general health) and four covering mental health (role emotional, vitality, social functioning, and mental health).

Quality of Life for Untreated Restless Legs Syndrome

The SF-36 has now been used in two population-based studies identifying individuals with RLS symptoms. The evaluation of RLS prevalence among elderly in Augsburg, Germany, used a standard clinical interview with a neurologic examination. The 369 participants completed the SF-36. RLS was diagnosed for 36 subjects (9.8%). Those with RLS compared with those without RLS showed on the SF-36 significantly (p <.05) lower scores for the mental health and depression dimensions. Although the vitality and role-physical scores were also lower for RLS, the differences were not statistically significant,17 but this was a small sample of older individuals (65 to 83 years old) who already have some compromise in physical health and vitality limiting somewhat sensitivity of the measure on these domains.

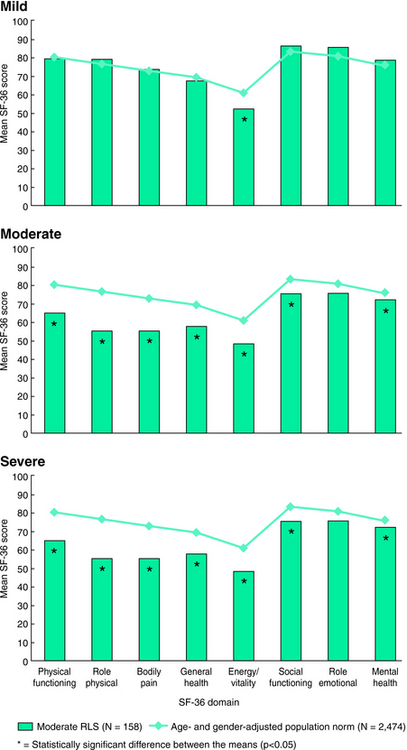

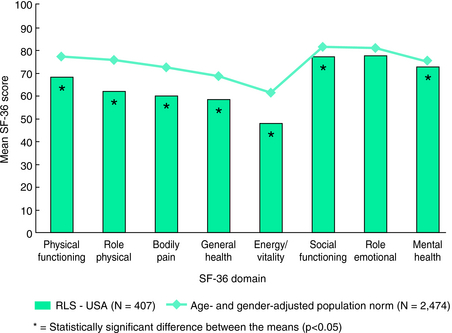

A larger population-based study used a validated set of questions to assess presence of RLS symptoms among 6014 subjects in the United States. The 187 subjects meeting criteria for having RLS symptoms also completed the SF-36 and rated their symptoms as either mild, moderate, or severe (including very severe).18 This population of those with RLS showed overall lower scores than those from an age- and gender-matched normal population on all domains except for role emotional19 (Fig. 37-2). Increasingly poorer scores on the SF-36 occurred for increasing severity of the symptoms (Fig. 37-3). Compared with the normative data, those with mild RLS symptoms showed significant differences only for energy/vitality; those with moderate RLS symptoms showed significant differences for all of the dimensions except role emotional; and those with severe RLS symptoms showed significant and dramatic impairments on all eight of the dimensions. There are some interesting differences between the American and somewhat younger sample of adults compared with the German elderly. Both studies showed significant decreased QoL for the mental health dimension and also reduced scores in the physical health dimensions, but for the American study the greater differences occurred for the physical health scores of bodily pain and role physical. Thus, we have a picture of mild RLS affecting most vitality, but moderate to severe RLS showing not only decreased vitality but also equally decreased role physical and bodily pain. This somewhat surprising picture of RLS indicates those with moderate to severe symptoms have marked impairment of QoL involving both vitality and physical limitations and pain. The issue of pain in RLS has to a large extent been ignored, although in the REST population-based study 59% reported pain with the symptoms and in another survey 56% of clinical patients with RLS similarly reported pain with RLS.20 Thus, the sensory discomfort of RLS appears to be both intense and at least as significant as the loss of energy or vitality for effects on QoL (see Chapter 27). This issue is of course confounded by the fact that sleep loss lowers pain thresholds; the sleep effects of RLS may be contributing not only to decreased vitality but also to increased pain. However, sleep loss by itself seems an inadequate explanation for the marked deficits seen on these dimensions of the SF-36 in RLS.

FIGURE 37-2. SF-36 for all with restless legs syndrome symptoms compared with age- and gender-matched norms.

From Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST General Population Study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1286-1292.

In addition, the SF-36 scores of those with mild to severe RLS symptoms in the American population–based study show similar impairment to that of other significant chronic diseases (Figs. 37-4 and 37-5). Moderate to severe RLS affects SF-36–based QoL as much as depression, osteoarthritis, congestive heart failure, or type 2 diabetes.19

These data provide strong support for the need to provide treatment for RLS.

Quality of Life for Treated Restless Legs Syndrome

Treatment effects on QoL are usually more clearly seen for disease-specific QoL measurements. Three such QoL scales have been developed. The first of these, developed at Johns Hopkins University and referred to as either the Hopkins RLSQoL or simply the RLSQoL, used expert opinion and patient support groups to develop a 18-item questionnaire covering a wide range of reported adverse effects of RLS on daily living. This test was found to have a valid total score with good psychometric properties (Chronbach alpha = 0.92, test-retest =0.84). The total score showed significant differences with even small changes in subjective report of symptoms occurring over a few weeks suggesting adequate responsiveness for treatment evaluation.21 This questionnaire was further evaluated in a two large clinical trial populations where the total score was again found to have very good psychometric properties and reasonable correlations of 0.67 or better with independent RLS severity ratings.22

The Johns Hopkins RLSQoL was used in two large placebo-controlled clinical trials evaluating benefits of a dopamine agonist (ropinirole) after 12 weeks of treatment. In both trials ropinirole showed an improvement in the RLSQoL score 25% greater than placebo.4,23 The degree of improvement was reasonably impressive, exceeding a 1 standard deviation change, which would be considered a large and clinically meaningful improvement in QoL. This has been the most widely used RLS specific quality of life scale. It has been used in most clinical trials and is available in well-validated translations in many languages from http://www.mapi-research.fr/.

The generic QoL SF-36 was also evaluated in these two large clinical trials and as expected showed less treatment effects than did the disease specific Johns Hopkins RLSQoL. In one of these trials conducted in 10 countries in Europe there were no significant changes noted in the SF-36 scores with treatment.23 The other clinical trial from centers in Europe, Australia, and North America, however, showed significantly greater improvement for ropinirole compared with placebo on 3 of the SF-36 domains, i.e., mental-health, social functioning, and vitality. The first two of these domains were not the ones with the biggest difference between those with and those without RLS symptoms, so why did these show responsiveness when the domains of role-physical and pain did not? One explanation may be furnished by study design: this study selected patients with only evening and nighttime symptoms and gave medication in one daily dose before bedtime with the goal of reducing late night symptoms and improving sleep. Although these were selected to be moderate to severe patients, the limitation of no daytime symptoms probably excluded the more severe RLS and thus the domains of pain and role-physical on the SF-36 were less likely to be reduced. They were, therefore, not the domains most expected to show treatment benefits. In contrast the study demonstrated the expected significant treatment benefit on sleep with improvement in the vitality domain. These differences regarding the significance of the pain and role-physical dimensions of QoL for different RLS populations needs to be further explored. It may represent a severity effect or possibly reflect differing phenotypes.

The second disease-specific QoL scale was developed based on a large convenience sample from the Internet of RLS patients, most of whom were receiving treatment. The diagnosis of these patients relied on their self-report, which was unlike the Johns Hopkins population, where the diagnosis was made by an experienced clinician. This second scale, referred to as the RLSQoL-1, has four distinguishable factors that were labeled: daily function, social function, sleep quality, and emotional well-being.24 This 17-item scale also has very good psychometric properties and it was used in one study of RLS patients, many of whom continued to have symptoms even if treated. The RLSQoL-1 results when analyzed in detail in relation to subjective report of sleep status indicated that a large part of the RLS impact on functioning was associated with the degree of sleep disturbance. Once the sleep status was considered, there appeared to be no further relation between the RLS severity and impact on functioning.25 This was a limited study, but it raised the possibility that the sleep disturbance produces most of the RLS impact on QoL. Again, however, the major dimensions of pain, discomfort, and role-physical were not adequately covered in any of the material used in this study.

The third specific QOL scale is the Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life (QoL-RLS) questionnaire.26 From a survey on 721 patients of North-German RLS advocacy groups, the item pool was determined by a content analysis of written reports from RLS patients on the consequences of their RLS disorder on everyday life functioning. The items are to be answered on a 6-point scale (0 = no impairment to 6 = very severe impairment). Factor analysis of a questionnaire combining the items resulted in one scale with 12 items. The most relevant item consists of a global rating of quality of life “all in all.” Further items are related to consequences of the RLS symptoms on sleep, activities of daily living, mood, and social interactions, to the consequences of disturbed sleep on everyday life and tiredness during the day and on mood as well as to consequences of pain and side effects of treatments on daily activities. A final section of the questionnaire asks for evaluation of coping behavior (effort of measures to get relief from the symptoms, avoidance of social situations, changes in lifestyle). Reliability estimates showed favorable psychometric qualities of the QoL-RLS (Cronbach’s α=.954). Intercorrelations of the total score from this QoL-RLS with RLS-6 severity scales (at time falling asleep, at night, during the day at rest, and during the day when active) were sufficiently high (around r = 0.60); however, the correlation to the total score of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) Rating Scale was exceptionally high (r = 0.925), indicating a presumably high affinity of the IRLS scale to quality of life. The QoL-RLS was applied in several clinical trials; in all these trials, the total score was more improved by active dopamine agonist therapy than by placebo27,28 or by levodopa.29 The instrument is available in several languages.

Conclusion

The morbidity of the RLS sleep disturbance appears to include cognitive deficits similar to those seen with one night’s sleep loss but does not include significant daytime sleepiness, suggesting there may be a hyperarousal with RLS during the daytime. Overall, the impact of the RLS sleep disturbance has unfortunately not been adequately studied. One limited study, however, suggested it was a primary contributor to the RLS effects on QoL.

The treatment results similarly show improved QoL on the disease specific QoL. The SF-36 results suggest some possible benefits for the sleep-related dimension of vitality and also for the mental health and social functioning but not for the role-physical or pain dimensions of the SF-36. This may reflect subject selection or again a failure to target treatment to address all aspects of RLS. Clearly, QoL evaluations should continue in future treatment trials. The SF-36 is widely available in multiple languages. The Johns Hopkins RLS-QoL has been translated into several languages and is available from MAPI-Research (http://www.mapi-trust.org/t_03_serv_dist_user.htm, where it is listed under J as the Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life questionnaire [RLS-QoL]). The QoL-RLS developed in Germany is available at http://www.kohnen@imerem.de.

1. Diagnostic Classification Steering Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association (M. Sateia, Chairperson). The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, Second Version. Chicago: American Association of Sleep Medicine, 2005.

2. Abetz L, Arbuckle R, Allen R, et al. The reliability, validity and responsiveness of the Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life questionnaire (RLSQoL) in a trial population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:79.

3. Saletu M, Anderer P, Saletu B, et al. sleep laboratory studies in restless legs syndrome patients as compared with normals and acute effects of ropinirole. 2. Findings on periodic leg movements, arousals and respiratory variables. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;41:190-199.

4. Walters AS, Ondo WG, Dreykluft T, et al. Ropinirole is effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. TREAT RLS 2: A 12-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1414-1423.

5. Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, et al. Ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: Results from the TREAT RLS 1 study, a 12 week, randomised, placebo controlled study in 10 European countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:92–97.

6. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Validation of the Johns Hopkins restless legs severity scale. Sleep Med. 2001;2:239-242.

7. Saletu M, Anderer P, Saletu B, et al. EEG mapping in patients with restless legs syndrome as compared with normal controls. Psychiatry Res. 2002;115:49.

8. Pearson VE, Allen RP, Dean T, et al. Cognitive deficits associated with restless legs syndrome (RLS). Sleep Med. 2006;7:25-30.

9. Harrison Y, Horne JA. Sleep loss impairs short and novel language tasks having a prefrontal focus. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:95-100.

10. Fallgatter AJ, Ehlis AC, Rösler M, et al. Diminished prefrontal brain function in adults with psychopathology in childhood related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2005;138:157-169.

11. Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring Functioning and Well-Being—The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC/London: Duke University Press, 1992.

12. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey—Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1993.

13. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

14. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724-735.

15. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220-233.

16. http://www.qualitymetric.com/products/sf8.aspx [online]. Available.

17. Rothdach AJ, Trenkwalder C, Haberstock J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of RLS in an elderly population: the MEMO study. Memory and Morbidity in Augsburg Elderly. Neurology. 2000;54:1064-1068.

18. Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286–1292.

19. Kushida C, Martin M, Nikam P, et al. Burden of restless legs syndrome on health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:617-624.

20. Bassetti CL, Mauerhofer D, Gugger M, et al. Restless legs syndrome: A clinical study of 55 patients. Eur Neurol. 2001;45:67-74.

21. Abetz L, Vallow SM, Kirsch J, et al. Validation of the Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life questionnaire. Value Health. 2005;8:157-167.

22. Abetz L, Arbuckle R, Allen R, et al. The reliability, validity and responsiveness of the Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life questionnaire (RLSQoL) in a trial population. Health Qual Life. 2005;3:79.

23. Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, et al. Ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: Results from the TREAT RLS 1 study, a 12 week, randomised, placebo controlled study in 10 European countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:92-97.

24. Atkinson MJ, Allen RP, DuChane J, et al. Validation of the Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life Instrument (RLS-QLI): Findings of a consortium of national experts and the RLS Foundation. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:679-693.

25. Kushida CA, Allen RP, Atkinson MJ. Modeling the causal relationships between symptoms associated with restless legs syndrome and the patient-reported impact of RLS. Sleep Medicine. 2004;5:485-488.

26. Kohnen R, Benes H, Heinrich CR, et al. Development of the disease-specific Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life (RLS-QoL) questionnaire. Seventh International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders (Movement Disorder Society), Miami 2002. Mov Disord 17(suppl. 5):743.

27. Oertel WH, Benes H, Bodenschatz R, et al. Efficacy of cabergoline in restless legs syndrome: A placebo-controlled study with polysomnography (CATOR). Neurology. 2006;67:1040-1046.

28. Trenkwalder C, Benes H, Grote L, et al. Cabergoline compared to levodopa in the treatment of patients with severe restless legs syndrome: Results from a multi-center, randomized, active controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2007;22:696-703.

29. Oertel WH, Benes H, Garcia-Borreguero D, et al. Efficacy of rotigotine transdermal system in severe restless legs syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, six-week dose-finding trial in Europe. Sleep Med. 2008;9:228-239.