Respiratory tract

4.1

Unilateral hypertransradiant hemithorax

Lung

1. Compensatory hyperexpansion – e.g. following lobectomy (look for rib defects/bronchial sutures indicating previous surgery) or lobar collapse.

2. Airway obstruction – air trapping on expiration results in increased lung volume and shift of the mediastinum to the contralateral side.

3. Unilateral bullae – vessels are absent rather than attenuated. May mimic pneumothorax.

4. Swyer–James (McLeod) syndrome – the late sequela of bronchiolitis in childhood (usually viral but non-viral organisms also implicated). Lung volume on affected side is either normal or slightly reduced but, importantly, there is air trapping on expiration. Ipsilateral hilar vessels are small. CT not infrequently shows bilateral disease with mosaic attenuation and bronchiectasis.

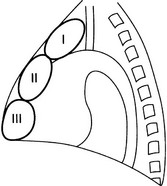

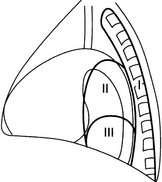

5. Congenital lobar emphysema – one-third present at birth. Marked overinflation of a lobe (most commonly left upper lobe followed by right upper lobe or right middle lobe). The ipsilateral lobes are compressed and there may be mediastinal displacement to the contralateral side.

4.2

Bilateral hypertransradiant hemithoraces

With overexpansion of the lungs

1. Emphysema – with large central pulmonary arteries and peripheral arterial pruning ± bullae; centrilobular emphysema typically in mid/upper zones whereas panacinar emphysema commonly affects lower zones.

2. Asthma – during an acute episode or with chronic disease with ‘fixed’ airflow obstruction due to airway remodelling.

3. Acute bronchiolitis – particularly affects children in the first year of life. Overexpansion is due to small airways (bronchiolar) obstruction. May be associated with large airway mucosal thickening leading to bronchial wall thickening on plain radiography. Collapse and consolidation are not primary features of bronchiolitis.

4. Tracheal, laryngeal or bilateral bronchial stenoses (see 4.3).

Engelke, C., Schaefer-Prokop, C., Schirg, E., et al. High-resolution CT and CT angiography of peripheral pulmonary vascular disorders. RadioGraphics. 2002; 22:739–764.

Frazier, A. A., Galvin, J. R., Franks, T. J., et al. Pulmonary vasculature: hypertension and infarction. RadioGraphics. 2000; 20:491–524.

4.3

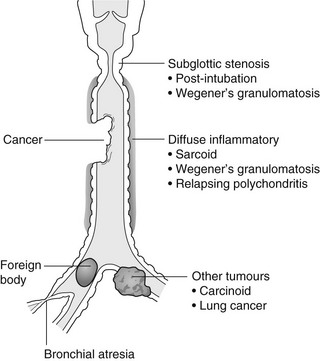

Tracheal/bronchial narrowing, stenosis or occlusion

In the lumen

1. Foreign body – air trapping is more common than atelectasis. The lower lobe is most frequently affected. The foreign body may be opaque. The column of air within the bronchus may be discontinuous (the ‘interrupted bronchus sign’).

2. Mucus plug – e.g. allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, asthma.

In the wall

1. Tracheal/lung cancer – narrowing ± irregularity.

2. Other tumours – e.g. carcinoid tumour – usually a smooth, rounded filling defect. Main bulk of tumour may lie outside the lumen of the airway.

3. Inflammation/fibrosis – e.g. sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, post-tuberculous, relapsing polychondritis.

4. Bronchial atresia – most commonly affecting the apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe.

5. Tracheobronchomalacia – excessive reduction (> 70% luminal calibre) in the calibre of the trachea/central airways at end-expiration. Diagnosis made on CT performed at residual volume or during dynamic expiration.

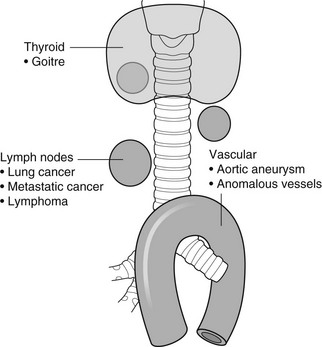

Outside the wall

2. Mediastinal tumours – smooth, eccentric narrowing.

5. Anomalous origin of left pulmonary artery from right pulmonary artery – producing compression of the right main bronchus as it passes over it, between the trachea and oesophagus to reach the left hilum. PA CXR shows the right side of the trachea to be indented and the vessel is seen end-on between the trachea and oesophagus on the lateral view.

Chung, J. H., Kanne, J. P., Gilman, M. D. Structured review article – CT of diffuse tracheal diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 196:W240–W246.

Prince, J. S., Duhamel, D. R., Levin, D. L., et al, Non-neoplastic lesions of the tracheobronchial wall: radiologic findings with bronchoscopic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2002;(Suppl):S215–S230.

4.4

Increased density of one hemithorax

With an undisplaced mediastinum

1. Consolidation/air-space opacification – indicating the replacement of air from the air spaces by exudate or other disease process (e.g. tumour, blood, oedema). An air bronchogram/bronchiologram may be present. Vascular margins and airway wall are obscured.

2. Pleural effusion – in the supine position, an uncomplicated effusion gravitates to the dependent part of the chest, producing a generalized increased density ± an apical ‘cap’ of fluid on CXR. Note that pulmonary vessels will be visible through the increased density (cf. Consolidation/air-space opacification). Erect or decubitus CXRs may confirm the diagnosis.

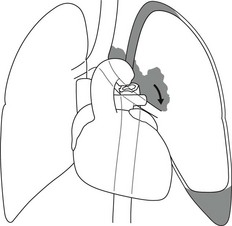

3. Malignant pleural mesothelioma – often associated with a pleural effusion which obscures the tumour ± calcified pleural plaques (more commonly demonstrated at CT). Encasement of the lung limits mediastinal shift. (NB. Affected hemithorax may even be smaller.)

With mediastinal displacement away from the dense hemithorax

1. Large pleural effusion (q.v.) – NB. A large effusion with no mediastinal shift indicates significant lung collapse (and, hence, central obstruction) or relative ‘fixation’ of the mediastinum (e.g. caused by malignant pleural mesothelioma).

2. Diaphragmatic hernia – on the right side with herniated liver; on the left side the hemithorax is not usually opaque because of air within the herniated bowel. The left hemithorax may be opaque in the early neonatal period when air has not yet had time to reach the herniated bowel.

With mediastinal displacement towards the dense hemithorax

3. Lymphangitis carcinomatosa – bilateral and symmetrical infiltration is most common; unilateral lymphangitis occurs more often in patients with lung cancer. Linear and nodular opacities ± ipsilateral hilar and mediastinal lymph-node enlargement. Septal lines. Pleural effusions are common.

4. Pulmonary agenesis and hypoplasia – usually asymptomatic. Absent or hypoplastic pulmonary artery.

4.5

Pulmonary air cysts

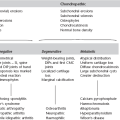

Postinfective

Cysts can appear during the first 2 weeks of the pneumonia and may resolve over several months.

Neoplastic

Diffuse lung diseases

1. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH) – cysts, sometimes with bizarre (i.e. non-circular) outlines, in mid/upper zones. In ‘early’ disease multiple nodules, which then cavitate. Relative sparing of lower zones and medial tips of middle lobe and lingula. Pulmonary LCH (but not other forms of LCH) is strongly linked to cigarette smoking.

2. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) – exclusively in female subjects of child-bearing age and related to mutation of TSC1 (chromosome 9). Smooth-muscle proliferation around vessels, lymphatics and airways. Cysts are a characteristic finding and more uniform in size than in LCH. No zonal predilection (cf. LCH).

3. Tuberose sclerosis (TSC) – neurocutaneous disorder associated with mutations of TSC1 and TSC2 genes. Pathology of lung disease in TSC almost identical to LAM.

4. Neurofibromatosis – cystic lung disease and interstitial fibrosis are reported but some doubt exists and changes maybe simply represent smoking-related interstitial lung disease.

5. Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome – autosomal dominant multisystem disorder characterized by pulmonary cysts, cutaneous fibrofolliculomas and increased risk of renal tumours. Recurrent pneumothoraces due to lung involvement.

6. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia – rarely idiopathic; usually occurs in context of dysproteinaemias, HIV infection and connective tissue disorders (in particular rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome). Mechanism of cyst formation is uncertain but may be caused by partial obstruction of small airways.

7. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis – possibly related to lymphocytic interstitial pulmonary infiltrate in subacute phase.

8. End-stage fibrotic diffuse interstitial lung diseases – e.g. idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Biyyam, D. R., Chapman, T., Ferguson, M. R., et al. Congenital lung abnormalities: embryologic features, prenatal diagnosis, and postnatal radiologic–pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2010; 30:1721–1738.

Seaman, D. M., Meyer, C. A., Gilman, M. D., McCormack, F. X. Pictorial essay: diffuse cystic lung disease at high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 196:1305–1311.

Silva, C. I. Diffuse lung cysts in lymphoid interstitial pneumonias: high-resolution CT and pathologic findings. J Thorac Imaging. 2006; 21:241–244.

4.6

Non-resolving or recurrent consolidation

1. Bronchial obstruction – e.g. caused by a tumour or foreign body.

2. Inappropriate antimicrobial therapy – e.g. tuberculosis, Klebsiella and fungal infection.

3. Malignancy – adenocarcinoma, lymphoma.

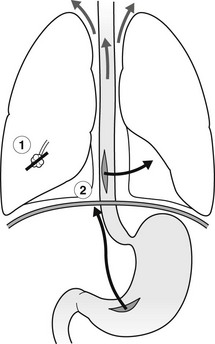

4. Recurrent aspiration – secondary to a pharyngeal pouch, achalasia, systemic sclerosis, hiatus hernia, ‘H’ type tracheo-oesophageal fistula, paralytic/neuromuscular disorders, chronic sinusitis.

5. Pre-existing lung pathology – e.g. bronchiectasis (see 4.10).

6. Impaired immunity – e.g. prolonged corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive therapy, immunoglobulin deficiency, diabetes, cachexia, HIV-related.

4.7

Consolidation with an enlarged hilum

Primary pneumonias

1. Primary tuberculosis – lymph-node enlargement is unilateral in 80% and involves the hilar (60%), or combined hilar and paratracheal (40%) nodes.

3. Mycoplasma pneumonia – lymph-node enlargement is common in children but rare in adults. May be unilateral or bilateral.

4. Primary histoplasmosis – in endemic areas. Hilar lymph-node enlargement is common, particularly in children. During healing, lymph nodes calcify and may cause bronchial obstruction, thereby initiating distal infection.

5. Coccidioidomycosis – in endemic areas. The pneumonic type consists of predominantly lower lobe consolidation that is frequently associated with hilar lymph-node enlargement.

4.8

Pneumonia involving part or the whole of one lobe

1. Streptococcal pneumonia – the commonest cause. Usually unilobar. Cavitation is rare. Pleural effusion is uncommon. Little or no collapse.

2. Klebsiella pneumonia – often multilobar involvement. High propensity for cavitation and lobar enlargement.

3. Staphylococcal pneumonia – especially in children. 40–60% of children develop pneumatocoeles. Effusion (empyema) and pneumothorax are also common. Bronchopleural fistula may develop. No lobar predilection.

4. Tuberculosis – in primary or postprimary tuberculosis, but more common in the former. Associated collapse is common. The right lung is affected more often than the left, and primary tuberculosis has a predilection for the anterior segment of the upper lobes or the medial segment of the middle lobe.

5. Streptococcus pyogenes pneumonia – affects the lower lobes predominantly. Often associated with pleural effusion/empyema.

4.9

Consolidation with bulging of fissures

Homogeneous or inhomogeneous air-space opacification with bulging of the bounding fissures.

1. Infection with abundant exudates – pneumonia caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae (Friedländer’s pneumonia), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Yersinia pestis (plague pneumonia).

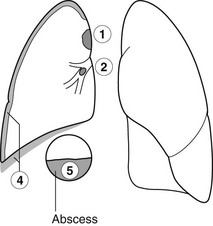

2. Abscess – when an area of consolidation breaks down. Organisms that commonly produce abscesses are Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp. and other Gram-negative organisms.

4.10

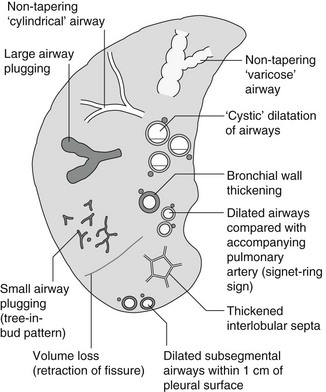

Bronchiectasis

Causes of bronchiectasis

Less frequent

1. Following childhood infections – e.g. secondary to measles and pertussis. Less common cause in the antibiotic era in developed countries but continues to be an important factor in developing countries.

2. Secondary to bronchial obstruction – foreign body, neoplasm, broncholithiasis or bronchial stenosis.

4. Congenital/genetic anomalies

(a) Kartagener’s syndrome – bronchiectasis with immobile cilia, dextrocardia and absent frontal sinuses. 5% of patients with dextrocardia will eventually develop bronchiectasis.

(b) Williams–Campbell syndrome – bronchial cartilage deficiency.

(c) Mounier–Kuhn syndrome – tracheobronchomegaly.

5. Collagen vascular diseases – particularly rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome.

6. Gastrointestinal disorders – ulcerative colitis, coeliac disease.

7. Immunological – allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, following solid-organ (heart/lung) or bone marrow transplantation.

Dodd, J. D., Souza, C. A., Müller, N. L. Conventional high-resolution CT versus helical high-resolution MDCT in the detection of bronchiectasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 187:414–420.

Hansell, D. M., Lynch, D. A., McAdams, H. P., Bankier, A. A., Diseases of the airways diseases. Imaging of diseases of the chest. 5th ed. Elsevier Mosby, Philadelphia, PA, 2010.

McGuinness, G., Naidich, D. P. CT of airways disease and bronchiectasis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002; 40(1):1–19.

4.11

Air-space opacification

Causes of air-space opacification

Note that any of the following may be unilateral and, in some instances, confined to a single lobe.

2. Infection – see also 4.7–4.9

(d) Influenza – particularly in patients with mitral stenosis or who are pregnant.

(e) Chicken pox (and other viral pneumonias) – may be confluent in the central areas of the lungs. ± Hilar lymph-node enlargement.

3. Diffuse pulmonary haemorrhage – e.g. idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis, anti-glomerular basement disease, microscopic polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet’s syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis, contusion, bleeding diatheses, Goodpasture’s syndrome, idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis (in the acute stage), pulmonary infarction.

4. Malignancy – adenocarcinoma, lymphoma.

5. Sarcoidosis* – called ‘air-space’ sarcoidosis and occurring in up to 20%. Air-space pattern is due to thickened interstitium and filling of air spaces by macrophages and granulomatous infiltration.

6. Eosinophilic lung disease – chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is characteristically non-segmental, in the upper zones and paralleling the chest wall.

7. Organizing pneumonia – may be cryptogenic or as a response to other ‘insult’ (e.g. infection, drug toxicity, connective tissue disease). Typically, multifocal air-space opacities in periphery of mid/lower zones. Occasionally a single focus may be present. A characteristic perilobular distribution is seen in some patients. Another pattern is the so-called ‘reverse halo’ or Atoll sign (a ring of consolidation surrounding central ground-glass opacification).

4.12

Pulmonary oedema

Non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

1. Fluid overload – excess i.v. fluids, renal failure and excess hypertonic fluids, e.g. contrast media.

2. Cerebral disease – cerebrovascular accident, head injury or raised intracranial pressure.

3. Near drowning – radiologically no significant radiological differences between freshwater and seawater drowning.

4. Aspiration (Mendelson’s syndrome).

5. Radiotherapy – several weeks following treatment. Ultimately has a characteristic straight edge as fibrosis ensues.

6. Rapid re-expansion of lung following thoracocentesis.

7. Liver disease and other causes of hypoproteinaemia.

8. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) – commonest cause of transfusion-related mortality in UK and USA. Onset of oedema is either during transfusion or within 1–2 hours.

(a) Those which induce cardiac arrhythmias or depress myocardial contractility (contrast media can induce arrhythmias, alter capillary wall permeability and produce a hyperosmolar load).

(b) Those which alter pulmonary capillary wall permeability, e.g. overdoses of heroin, morphine, methadone, cocaine, ‘crack’, dextropropoxyphene and aspirin. Hydrochlorothiazide, phenylbutazone, aspirin and nitrofurantoin can cause oedema as an idiosyncratic response; interleukin-2 and tumour necrosis factor may cause increased permeability by an unknown pathophysiological process.

11. Mediastinal tumours – producing venous or lymphatic obstruction.

12. Acute respiratory distress syndrome – may be primary (e.g. caused by severe pneumonia, aspiration) or secondary (e.g. following non-thoracic sepsis or trauma); CXR may be normal in first 24 hours but progressive widespread opacification with onset of interstitial and then frank intra-alveolar leak of oedema and haemorrhagic fluid.

13. High altitude (acute mountain sickness) – following rapid ascent to > 3000 metres.

Asrani, A. Urgent findings in portable chest radiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 196:WS37–WS46.

Gluecker, T., Capasso, P., Schnider, P., et al. Clinical and radiologic features of pulmonary edema. RadioGraphics. 1999; 19:1507–1531.

Desai, S. R., Wells, A. U., Suntharalingam, G., et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pulmonary and extrapulmonary injury: a comparative CT study. Radiology. 2001; 218:689–693.

Desai, S. R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: imaging the injured lung. Clin Radiol. 2002; 57:8–17.

4.13

Unilateral pulmonary oedema

Pulmonary oedema on the same side as a pre-existing abnormality

4.14

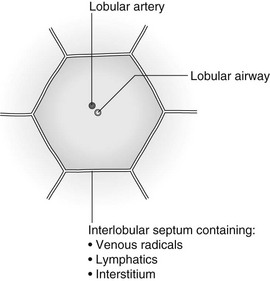

Septal (Kerley B) lines

Lymphatic/interstitial infiltration

1. Lymphangitis carcinomatosa/lymphomatosa – most often caused by lymphatic infiltration in patients with cancer of the lung, breast, stomach and pancreas or lymphoma. Nodular thickening (typically bilateral) of interlobular septa is the characteristic finding on CT.

2. Pneumoconioses – surrounding tissues may contain a heavy metal, e.g. tin, which contributes to the density.

3. Sarcoidosis* – septal lines are uncommon.

4. Idiopathic bronchiectasis – thickened interlobular septa are a feature in around one-third of patients (see 4.10).

5. Erdeim–Chester disease – infiltration of pulmonary interstitium by histiocytes of non-Langerhans’ type. Primarily a bone disorder but extraskeletal involvement in around 50%. Lung involvement in around one-third of patients. On chest radiography, reticulonodular infiltrate in mid/upper zones. On CT, smooth thickening of interlobular septa is characteristic, associated with ground-glass opacification and centrilobular nodules.

6. Diffuse pulmonary haemorrhage – with recurrent episodes of bleeding, thickened interlobular septa may be seen on CT (see 4.11).

7. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis – proliferation of lymphatic channels in pleura, interlobular septa and peribronchovascular connective tissue.

8. Congenital lymphangiectasia – abnormal dilatation of lymphatic vessels. (NB. No increase in number of lymphatics; cf. lymphangiomatosis.) May be associated with extrathoracic congenital anomalies (e.g. renal, cardiac). Usually fatal.

9. Alveolar proteinosis – smooth thickening of interlobular (and intralobular) septa in geographical areas of ground-glass infiltration (i.e. the ‘crazy-paving’ pattern). Infiltration of air spaces and interstitium and air spaces by PAS-positive macrophages.

4.15

Reticular pattern (with or without honeycombing)

Reticular pattern – diffuse interstitial lung diseases

1. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) – most common idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Associated with the histological/radiological pattern of UIP. Typical patient is male, aged 50–60 years and complaining of progressive dyspnoea. On CXR there is a reticular pattern in mid/lower zones. Predominant basal and subpleural reticular pattern with honeycombing is the characteristic finding on CT. Ancillary findings include ground-glass opacification (less extensive than reticular pattern), traction bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis and mediastinal lymph-node enlargement. Atypical HRCT findings in around 30–50%. Coexistent emphysema in upper zones (associated with preserved lung volumes). Increased incidence of lung cancer.

2. Connective tissue diseases (CTDs) – fibrotic lung disease is common and most frequent cause of death. Variable patterns of interstitial lung disease including UIP, NSIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP; see also 4.5) and diffuse alveolar damage. Variable prevalence in different CTDs: UIP pattern more prevalent than NSIP in rheumatoid arthritis; NSIP pattern more prevalent in systemic sclerosis and polymyositis/dermatomyositis; LIP most prevalent in rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome.

(a) Asbestosis: basal and subpleural fibrosis, almost indistinguishable from IPF on histopathology and radiology although fibrosis may be coarser in asbestosis than IPF and pleural abnormalities absent in IPF. Long latency period (> 20 years) following exposure.

(b) Hard metal pneumoconiosis: exposure to alloys of tungsten, carbon and cobalt ± other metals.

(c) Paraquat poisoning: late phase of poisoning associated with pulmonary fibrosis.

4. Sarcoidosis* – archetypal granulomatous fibrotic diffuse interstitial lung disease. Typically associated with symmetrical, bronchocentric reticular pattern in upper zones. Calcified mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes.

5. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis – secondary to repeated exposure to a potentially wide variety of particulate (1–5 µm diameter) organic antigens originating from animals, plants, drugs or bacteria/fungi. A reticular pattern ± honeycombing, ground-glass opacification ± traction bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis and lobular areas of apparently ‘spared’ lung are characteristic on CT.

6. Cystic lung diseases – because of the effects of anatomical superimposition on chest radiographs, the multiple cysts in disorders such as Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and tuberous sclerosis can manifest as a reticular pattern (see also 4.5). Relative preservation of lung volumes.

7. Drug-induced lung disease – e.g. caused by nitrofurantoin, busulphan, cyclophosphamide, bleomycin and melphalan.

8. Bone marrow transplantation – airways disease (constrictive obliterative bronchiolitis) and upper zone fibrosis associated with recurrent small pneumothoraces.

Reticular pattern – due to parenchymal destruction leaving ‘remnant’ interlobular septa

Seen in α1-antitrypsin deficiency-related emphysema; seen in the lower zones.

Dixon, S., Benamore, R. The idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: understanding key radiological features. Clin Radiol. 2010; 65:823–831.

Raghu, G., Collard, H. R., Egan, J. J., et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis evidence-based guideline for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 183:788–824.

Wells, A. U., Hirani, N. Interstitial lung disease guideline. Thorax. 2008; 63(Suppl V):v1–v58.

4.16a

Multiple small (‘pin-point’) micronodules

Must be of very high atomic number to be rendered visible on plain chest radiography.

1. Post lymphangiography – iodized oil emboli. Contrast medium may be visible at the site of termination of the thoracic duct.

2. Silicosis* – usually larger than pin-point but can be very dense, especially in gold miners.

3. Stannosis – inhalation of tin oxide. Even distribution throughout the lungs. With Kerley A and B lines.

4. Barytosis – inhalation of barytes. Very dense, discrete opacities. Generalized distribution but bases and apices usually spared.

5. Limestone and marble workers – inhalation of calcium.

6. Alveolar microlithiasis – familial disorder. Lung detail obscured by miliary calcifications. Few symptoms but may progress to cor pulmonale. Pleura, heart and diaphragm may be seen as ‘negative’ shadows.

4.16b

Multiple micronodules (0.5–2 mm)

Soft-tissue or ground-glass attenuation

1. Miliary tuberculosis – widespread and secondary to haematogenous dissemination. Uniform size. Indistinct margins but discrete. No septal lines. Normal hila unless superimposed on primary tuberculosis.

2. Fungal infection – histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis and Cryptococcus (torulosis). Similar appearance to miliary tuberculosis.

3. Coal miner’s pneumoconiosis* – predominantly mid zones with sparing of the extreme bases and apices. Ill-defined and may be arranged in a circle or rosette. Septal lines.

4. Sarcoidosis* – predominantly upper/mid zones and strikingly bronchocentric (causing ‘bronchovascular beading’) ± enlarged hilar lymph nodes.

Greater than soft-tissue density

1. Haemosiderosis – secondary to chronic raised venous pressure (seen in 10–15% of patients with mitral stenosis), repeated pulmonary haemorrhage (e.g. Goodpasture’s disease) or idiopathic (see also 4.11). Septal lines. Smaller than miliary tuberculosis.

2. Silicosis* – relative sparing of bases and apices. Very well-defined and dense when due to inhalation of pure silica: ill-defined and of lower density when due to mixed dusts. Septal lines.

3. Siderosis – lower density than silica. Widely disseminated. Asymptomatic.

4.16c

Multiple opacities (2–5 mm)

Soft-tissue or ground-glass attenuation and remaining discrete

1. Disseminated cancer – breast, thyroid, sarcoma, melanoma, prostate, pancreas or lung (eroding a pulmonary artery). Variable sizes and progressive increase in size. ± Lymphatic obstruction.

2. Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis* – centrilobular nodules, ground-glass opacification, lobular foci of decreased attenuation, ± scattered thin-walled cysts. Smoking has a ‘protective’ effect (cf. respiratory bronchiolitis).

3. Respiratory bronchiolitis – (similar CT appearances to hypersensitivity pneumonitis but invariably linked to smoking) multiple centrilobular nodules, together with ground-glass opacification, lobular air trapping (on expiratory CT), thickened interlobular septa and limited emphysema.

4. Lymphoma* – usually with hilar or mediastinal lymph-node enlargement.

5. Sarcoidosis* – predominantly upper/mid zones and strikingly bronchocentric ± enlarged hilar lymph nodes.

4.17

Solitary pulmonary nodule

Granulomatous

1. Tuberculoma – more common in the upper lobes and on the right side. Well-defined; 0.5–4 cm. 25% are lobulated. Calcification frequent. 80% have satellite lesions. Cavitation is uncommon and, if present, is small and eccentric. Usually persist unchanged for years.

2. Histoplasmoma – in endemic areas (Mississippi and the Atlantic coast of USA). More frequent in the lower lobes. Well-defined. Seldom larger than 3 cm. Calcification is common and may be central, producing a target appearance. Cavitation is rare. Satellite lesions are common.

Malignant tumours

1. Lung cancer – usually > 2 cm. Accounts for less than 15% of all solitary nodules at 40 years; almost 100% at 80 years. However, up to 38% of small (< 1 cm) nodules identified by CT may be primary lung cancer. Radiological appearances suggesting malignancy include: recent appearance or rapid growth (review previous CXRs); size greater than 4 cm; the lesion crosses a fissure (although some fungal infections may also do so); ill-defined margins; umbilicated or notched margin (if present it indicates malignancy in 80%); corona radiata (spiculation) (but also seen in PMF and granulomas); peripheral line shadows. Calcification is rare (but seen in up to 10% at CT). Most lung cancers appear ‘solid’ on CT although foci of low (fluid) attenuation, denoting necrosis, may be present. Recent evidence points to significance of pure ground-glass/part-solid ground-glass nodules larger than 5 mm diameter and indicates that these may represent premalignant lesions, adenocarcinoma in situ or malignant adenocarcinoma.

2. Solitary metastasis – accounts for 3–5% of asymptomatic nodules. 25% of pulmonary metastases may be solitary. Most likely primary tumours are breast, sarcoma, seminoma and renal cell carcinoma. Predilection for the lung periphery. Calcification is rare but when present suggests metastatic osteosarcoma, or chondrosarcoma. When considering the diagnosis of pulmonary metastases in children the following points must be borne in mind:

(a) In contrast to adults, it is highly unlikely that there will be an incidental finding of pulmonary metastatic disease.

(b) The majority of single lung nodules are benign and even in a child with known malignancy one-third of new lung nodules may be benign.

(c) Multiple lung nodules are more likely to be malignant than a single nodule.

(d) Therapy usually results in complete resolution of a metastatic nodule but occasionally there may be a residual scar.

3. Rare malignant lung tumours – pulmonary blastoma, pulmonary sarcoma, plasmacytoma, atypical carcinoid (see below).

Benign tumours

1. Carcinoid tumour – ‘typical’ carcinoids account for majority (90%) of cases and tend to be more benign than atypical (accounting for 10%) tumours. However, the spectrum of biological behaviour is wide ranging, from benign to frank small cell carcinoma. Typical carcinoids are generally central whereas atypical tumours tend to be peripheral. May be associated with ectopic ACTH production (Cushing’s syndrome).

2. Hamartoma – 96% occur over 40 years. 90% are intrapulmonary and usually within 2 cm of the pleura. 10% cause bronchial stenosis. Usually < 4 cm diameter. Well-defined. Lobulated rather than smooth. Calcification in 30%, although incidence rises with the size of the lesion (in 75% when > 5 cm). Calcification may have a ‘pop-corn’ configuration, craggy or punctate.

Infectious/inflammatory

1. Pneumonia – especially pneumococcal.

2. Hydatid – in endemic areas. Most common in the lower lobes and more frequent on the right side. Well-defined. 1–10 cm. Solitary in 70%. May have a bizarre shape. Rupture results in the ‘water lily’ sign.

3. Rounded atelectasis – typically a sequela of an exudative (inflammatory) pleural effusion. Mass associated with adjacent smooth pleural thickening and parenchymal bands giving rise to ‘comet tail’ appearance.

4. Wegener’s granulomatosis – solitary nodules in up to one-third of patients but more commonly multiple (see 4.18).

5. Sarcoidosis* – a solitary lung nodule (simulating malignancy) is rare but recognized.

6. Organizing pneumonia – can masquerade as a (malignant) solitary pulmonary nodule (see also 4.11).

Congenital

1. Sequestration – may be intralobar (more common; acquired abnormality probably secondary to chronic lung suppuration; no separate pleural covering; venous drainage into pulmonary veins) or extralobar (rare; congenital lesion with separate pleural covering; venous drainage into systemic circulation). Usually large (> 6 cm). Majority in the left lower lobe; next most common site is the right lower lobe, contiguous with the diaphragm. Well-defined, round or oval. Diagnosis confirmed by identification of the mass and its blood supply: increasingly possible with advent of multidetector CT; MR angiography also of value in demonstration of anomalous vasculature.

2. Bronchogenic cyst – majority are mediastinal or hilar but occasional bronchogenic cysts are intrapulmonary (even more rarely: diaphragmatic, pleural or pericardial). Most intrapulmonary/bronchogenic cysts are central (perihilar) and may have a systemic arterial supply. Round or oval. Smooth-walled and well-defined.

3. Intrapulmonary lymph node – usually solitary, small (< 2 cm), well-defined and discovered incidentally at CT in mid/lower zones. Vast majority within 2 cm of visceral pleura. Accounting for around 20% of all incidentally-detected solitary nodules. Usually benign (even when detected in context of a known malignancy).

Vascular

1. Haematoma – peripheral, smooth and well-defined. 2–6 cm. Slow resolution over several weeks.

2. Arteriovenous malformation – 66% are single. Well-defined, lobulated lesion. Feeding or draining vessels may be demonstrable. Calcification rare. Pulmonary angiography previously the gold standard for diagnosis but now supplanted by multidetector CT.

Naidich, D. P., Bankier, A. A., MacMahon, H., et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2013; 266:304–317.

Travis, W. D., Brambilla, E., Noguchi, M., et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011; 6:244–285.

Winer-Muram, H. The solitary pulmonary nodule. Radiology. 2006; 239:34–49.

4.18

Multiple pulmonary nodules (> 5 mm)

Neoplastic

1. Metastases – most commonly from breast, thyroid, kidney, gastrointestinal tract and testes. In children, Wilms’ tumour, Ewing’s sarcoma, neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma. Predilection for lower lobes and more common peripherally. Range of sizes. Well-defined. Ill-definition suggests prostate, breast or stomach. Hilar lymphadenopathy and effusions are uncommon.

Infections

1. Abscesses – widespread distribution but asymmetrical. Commonly Staphylococcus aureus. Cavitation common. No calcification.

2. Coccidioidomycosis – in endemic areas. Well-defined with a predilection for the upper lobes. 0.5–3 cm. Calcification and cavitation may be present.

3. Histoplasmosis – in endemic areas. Round, well-defined and few in number. Sometimes calcify. Usually unchanged for many years.

4. Hydatid – more common on the right side and in the lower zones. Well-defined unless there is surrounding pneumonia. Often 10 cm or more. May rupture and show the ‘water lily’ sign.

Immunological

1. Wegener’s granulomatosis – bilateral nodules or masses (± cavitation in 30–50% of cases) or unifocal/multifocal consolidation. Widespread distribution. Round and well-defined. No calcification. Cavitation.

2. Rheumatoid nodules – peripheral and more common in the lower zones. Round and well-defined. No calcification. Cavitation common.

3. Caplan’s syndrome – well-defined nodules. Develop rapidly in crops. Calcification and cavitation occur. Background stippling of pneumoconiosis.

4. Sarcoidosis – multiple nodules/masses, measuring up to 5 cm, are an uncommon but recognized manifestation.

5. Organizing pneumonia (see also 4.11).

6. Amyloidosis – multiple nodules of varying size (calcified in up to 50%).

Orseck, M. J., Player, K. C., Woollen, C. D., et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia mimicking multiple pulmonary metastases. Am Surg. 2000; 66:11–13.

Trousse, D. Synchronous multiple primary lung cancer: an increasing clinical occurrence requiring multidisciplinary management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007; 133:1193–1200.

4.19

Lung cavities

A cavity is any gas-filled space in an area of consolidation, nodule or mass.

Infective

1. Staphylococcus aureus – thick-walled with a ragged inner lining. Usually multiple; no lobar predilection. Associated with effusion and empyema ± pyopneumothorax – almost invariable in children but less common in adults.

2. Klebsiella pneumoniae – thick-walled with a ragged inner lining. More common in the upper lobes. Usually single but may be multilocular ± effusion.

3. Tuberculosis – thick-walled and smooth. Upper lobes and apical segment of lower lobes mainly. Usually surrounded by consolidation ± fibrosis.

4. Aspiration – look for foreign body, e.g. tooth.

5. Others – Gram-negative organisms, actinomycosis, nocardiosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, aspergillosis, hydatid and amoebiasis.

Neoplastic

1. Lung cancer – thick-walled with an eccentric cavity. Predilection for the upper lobes. Found in 2–10% of carcinomas and especially if peripheral. More common in squamous cell carcinomas and may then be thin-walled (see also 4.17).

2. Metastases – thin- or thick-walled. May involve only a few of the nodules. Seen especially in squamous cell, colon and sarcoma metastases.

3. Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease) – thin- or thick-walled and typically in an area of infiltration. With hilar/mediastinal lymph-node enlargement.

Vascular

Infarction – primary infection due to a septic embolus commonly results in cavitation. There may be secondary infection of an initially sterile infarct. An aseptic cavitating infarct may subsequently become infected: tertiary infection. Aseptic cavitation is usually solitary and arises in a large area of consolidation after about 2 weeks. If localized to a segment, the commonest sites are apical or the posterior segment of an upper lobe or apical segment of lower lobe (cf. lower lobe predominance with non-cavitating infarction). Majority have scalloped inner margins and cross-cavity band shadows ± effusion.

In abnormally modelled/destroyed lung or congenital

1. Infected emphysematous bulla – thin-walled. ± Air–fluid level.

2. Sequestrated segment – thick- or thin-walled. 66% in the left lower lobe, 33% in the right lower lobe. ± Air–fluid level. ± Surrounding pneumonia.

3. Bronchogenic cyst – in medial third of lower lobes. Thin-walled. ± Air–fluid level. ± Surrounding pneumonia.

Inflammatory

1. Wegener’s granulomatosis – cavitation in some of the nodules. Thick-walled, becoming thinner with time. Can be transient.

2. Rheumatoid nodules – thick-walled with a smooth inner lining. Especially in the lower lobes and peripherally. Well-defined. Become thin-walled with time.

3. Progressive massive fibrosis – predominantly in the mid and upper zones. Thick-walled and irregular. Background nodularity.

4. Sarcoidosis* – thin-walled. In early disease due to a combination of central necrosis of areas of coalescent granulomas and a check-valve mechanism beyond partial obstruction of airways by endobronchial sarcoidosis.

4.20

Non-thrombotic pulmonary emboli

1. Septic embolism – associated with indwelling venous catheters, tricuspid valve endocarditis and peripheral septic thrombophlebitis. Variable size, poorly marginated nodules, predominantly in the lower lobes which may cavitate.

3. Fat embolism – 1–2 days post-trauma. Predominantly peripheral. Resolves in 1–4 weeks. Normal heart size. Pleural effusions uncommon. Neurological symptoms in up to 85% and skin abnormalities in 20–50%.

4. Venous air embolism – when iatrogenic, prognosis is affected by volume of air and speed of injection. Clinical effects are the result of right ventricular outflow obstruction or obstruction of pulmonary arterioles. CXR may be normal or show air in the main pulmonary artery, heart or hepatic veins, focal pulmonary oligaemia or pulmonary oedema.

5. Amniotic fluid embolism – rare. The majority of patients suffer cardiopulmonary arrest and the CXR shows pulmonary oedema.

6. Tumour embolism – common sources are liver, breast, stomach, kidney, prostate and choriocarcinoma. CXR is usually normal.

7. Talc embolism – in i.v. drug abusers.

8. Iodinated oil embolism – following contrast lymphangiography.

9. Cotton embolism – when cotton fibres adhere to angiographic catheters or guidewires and in i.v. drug abusers.

4.21

Pulmonary calcification or ossification

Localized

1. Tuberculosis – demonstrable in 10% of those with a positive tuberculin test. Small central nidus of calcification. Calcification ≠ healed.

2. Histoplasmosis – in endemic areas, calcification due to histoplasmosis is demonstrable in 30% of those with a positive histoplasmin test. Calcification may be laminated, producing a target lesion. ± Multiple punctate calcifications in the spleen.

Calcification in a solitary nodule

Calcification within a nodule generally equates with benignity. The exceptions are:

(a) Lung cancer ‘engulfing’ a pre-existing calcified granuloma (eccentric calcification).

(b) Solitary calcifying/ossifying metastasis – osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon or breast, papillary carcinoma of the thyroid, cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary and carcinoid.

(c) Primary peripheral squamous cell or papillary adenocarcinoma.

Diffuse or multiple calcifications

(a) Tuberculosis – healed miliary.

(c) Varicella – following chicken pox pneumonia in adulthood. 1–3 mm. Numbered in 10s.

2. Chronic pulmonary venous hypertension – especially mitral stenosis. Up to 8 mm. Most prominent in mid and lower zones. ± Ossification.

3. Silicosis – in up to 20% of those showing nodular opacities.

5. Alveolar microlithiasis – often familial. Myriad minute calcifications in alveoli which obscure all lung detail. Because of the increased lung density, the heart, pleura and diaphragm may be seen as negative shadows.

6. Metastatic due to hypercalcaemia – chronic renal failure, secondary hyperparathyroidism and multiple myeloma*. Predominantly in the upper zones.

Interstitial ossification

1. Dendriform/disseminated pulmonary ossification. Branching or nodular calcific densities extending along the bronchovascular distribution of the interstitial space. Seen in long-term busulphan therapy, chronic pulmonary venous hypertension (e.g. due to mitral stenosis), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, asbestosis, following ARDS, chronic bronchitis.

4.22

Unilateral hilar enlargement

Lymph nodes

1. Lung cancer – hilar enlargement may be tumour itself or malignant lymph nodes.

2. Lymphoma* – unilateral is very unusual; involvement is usually bilateral and asymmetrical.

4. Sarcoidosis* – unilateral disease in only 1–5%.

Pulmonary artery

1. Poststenotic dilatation – on the left side.

2. Pulmonary embolus (see Pulmonary embolic disease*) – massive embolus to one lung. Peripheral oligaemia.

3. Aneurysm – in chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension. ± Egg-shell calcification.

4.23

Bilateral hilar enlargement

Caused by lymph-node or pulmonary artery enlargement.

Idiopathic

Sarcoidosis* – symmetrical and lobulated. Bronchopulmonary ± unilateral or bilateral paratracheal lymph node enlargement.

4.24

‘Egg-shell’ calcification of lymph nodes

1. Silicosis* – seen in approximately 5% of silicotics. Predominantly affecting hilar lymph nodes but may also be observed in the nodal groups. Calcification more common in complicated pneumoconiosis. Lungs show multiple small nodular shadows or areas of massive fibrosis.

2. Coal miner’s pneumoconiosis* – occurs in only 1% of cases. Associated pulmonary changes include miliary shadowing or massive shadows.

3. Sarcoidosis* – nodal calcification overall in approximately 5% of patients and is occasionally ‘egg-shell’ in appearance. Calcification appears about 6 years after the onset of the disease and is almost invariably associated with advanced pulmonary disease and in some cases with steroid therapy.

4. Lymphoma following radiotherapy – appears 1–9 years after radiotherapy.

4.25

Diffuse lung disease with preserved lung volumes

1. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis*.

2. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis/tuberose sclerosis complex.

4. Sarcoidosis* – obstruction of small airways is often a dominant finding in sarcoidosis.

4.27

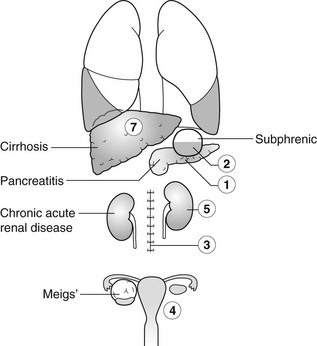

Pleural effusion due to extrathoracic disease

1. Pancreatitis – acute, chronic or relapsing. Effusions are predominantly left-sided. Elevated amylase content.

2. Subphrenic abscess – with elevation and restriction of movement of the ipsilateral diaphragm and basal atelectasis or consolidation.

3. Following abdominal surgery – most often seen on the side of the surgery and larger after upper abdominal surgery. Disappears after 2 weeks.

4. Meigs’ syndrome – pleural effusion + ascites + benign pelvic tumour (most commonly an ovarian fibroma, thecoma, granulosa cell tumour or cystadenoma).

4.28

Pleural effusion with an otherwise normal chest X-ray

Effusion may be the only abnormality or other signs may be obscured by the effusion.

Neoplastic

1. Carcinoma of the bronchus – effusion occurs in 10% of patients and a peripheral carcinoma may be hidden by the effusion.

2. Metastases – most commonly from breast; less commonly pancreas, stomach, ovary and kidney. Look for evidence of surgery.

3. Mesothelioma – effusion in 90%; often massive and obscures the underlying pleural disease.

4. Lymphoma* – effusion occurs in 30% but is usually associated with lymphadenopathy or pulmonary infiltrates.

Immunological

1. Systemic lupus erythematosus* – effusion is the sole manifestation in 10% of cases. Usually small but may be massive. Bilateral in 50%. 35–50% of those with an effusion have associated cardiomegaly.

2. Rheumatoid disease (see Rheumatoid arthritis*) – observed in 3% of patients. Almost exclusively males. Usually unilateral and may predate joint disease. Tendency to remain unchanged for a long time.

Others

1. Pulmonary embolus (see Pulmonary embolic disease*) – effusion is a common sign and it may obscure an underlying area of infarction.

2. Closed chest trauma – effusion may contain blood, chyle or food (due to oesophageal rupture). The latter is almost always left-sided.

3. Asbestosis* – mesothelioma and carcinoma of the bronchus should be excluded but an effusion may be present without these complications. Effusion is frequently recurrent and usually bilateral. Usually associated with pulmonary disease.

4.29

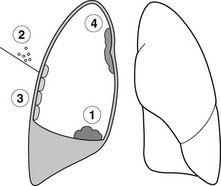

Pneumothorax

1. Spontaneous – M : F = 8 : 1. Especially those of tall thin stature, usually due to ruptured blebs or bullae. 20% are associated with a small pleural effusion.

2. Iatrogenic – following chest aspiration, artificial ventilation, lung biopsy or central line insertion.

3. Trauma – may be associated with rib fractures, haemothorax, surgical emphysema or mediastinal emphysema.

4. Secondary to mediastinal emphysema (see 4.30).

(e) Bronchopleural fistula, e.g. due to lung abscess or carcinoma.

(f) Lung neoplasms – especially metastases from osteogenic sarcomas and other sarcomas.

6. Pneumoperitoneum – air passage through a pleuroperitoneal foramen.

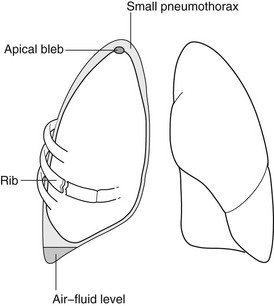

4.30

Pneumomediastinum

1. Lung tear – a sudden rise in intra-alveolar pressure, often with airway narrowing, causes air to dissect through the interstitium to the hilum and then to the mediastinum.

(a) Spontaneous – the most common cause and may follow coughing or strenuous exercise.

(b) Asthma – but usually not < 2 years of age.

(c) Severe and protracted vomiting.

(d) Vaginal delivery because of repeated Valsalva manoeuvres.

2. Perforation of oesophagus, trachea or bronchus – ruptured oesophagus is often associated with a hydrothorax or hydropneumothorax, usually on the left side.

3. Perforation of a hollow abdominal viscus – with extension of gas via the retroperitoneal space.

Katabathina, V. S., Restrepo, C. S., Martinez-Jimenez, S., Riascos, R. F. Nonvascular, nontraumatic mediastinal emergencies in adults: a comprehensive review of imaging findings. RadioGraphics. 2011; 31:1141–1160.

Lee, S. Y., Chen, C. H., Sheu, C. Y., et al. The radiological manifestations of the aberrant air surrounding the pleura: in the embryological view. Pulm Med. 2012; 2012:290802.

Zylak, C. M., Standen, J. R., Barnes, G. R., et al. Pneumomediastinum. RadioGraphics. 2000; 20:1043–1057.

4.32

Unilateral elevated hemidiaphragm

Causes above the diaphragm

1. Phrenic nerve palsy – smooth hemidiaphragm. No movement on respiration. Paradoxical movement on sniffing. The mediastinum is usually central. The cause may be evident on the X-ray.

3. Pulmonary infarction – see Pulmonary embolic disease*.

4. Pleural disease – especially old pleural disease, e.g. haemothorax, empyema or thoracotomy.

5. Splinting of the diaphragm – associated with rib fractures or pleurisy or subphrenic abcess.

Differential diagnosis

1. Subpulmonary effusion – movement of fluid is demonstrable on a decubitus film. On the left side there is increased distance between the lung and stomach fundal gas. On the right side the normal liver makes assessment more difficult.

2. Ruptured diaphragm – more common on the left. Barium meal confirms the diagnosis.

4.33

Bilateral elevated hemidiaphragms

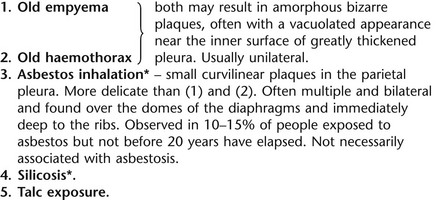

4.35

Local pleural masses

1. Loculated pleural effusion.

2. Metastases – from bronchus or breast. Often multiple.

3. Malignant mesothelioma – nearly always related to asbestos exposure. The pleural thickening may be obscured by an effusion. Often associated with a small hemithorax.

4. Solitary fibrous tumour of the pleura (SFT) (previously called pleural fibroma) – 20% contain malignant elements. Usually a smooth lobular mass, 2–15 cm diameter, arising more frequently from the visceral pleura than the parietal pleura. May change position due to pedunculation. Forms an obtuse angle with the chest wall suggesting extrapulmonary location. Patients usually over 40 years of age and asymptomatic. When SFT is present, there is a high chance of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy.

4.36

Rib lesion with an adjacent soft-tissue mass

Neoplastic

1. Bronchogenic carcinoma – solitary site unless metastatic.

2. Metastases – solitary or multiple.

3. Multiple myeloma* – classically multiple sites and bilateral.

4. Mesothelioma – rib destruction occurs in 12%.

Infective

1. Tuberculosis osteitis – commonest inflammatory lesion of a rib but a rare manifestation of tuberculosis. Second only to malignancy as a cause of rib destruction. Clearly defined margins ± abscess.

2. Actinomycosis – usually a single rib and often associated with a lung mass due to consolidation.

4. Blastomycosis – adjacent patchy or massive consolidation ± hilar lymphadenopathy.

Mullan, C. P., Madan, R., Trotman-Dickenson, B., et al. Radiology of chest wall masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 197:W460–W470.

Restrepo, R., Lee, E. Y. Updates on imaging of chest wall lesions in pediatric patients. Semin Roentgenol. 2012; 47:79–89.

Steiner, R. M., Cooper, M. W., Brodovsky, H. Rib destruction: a neglected finding in malignant mesothelioma. Clin Radiol. 1982; 33:61–65.

4.37

Chest radiograph following chest trauma

Pleura

1. Pneumothorax – simple (in 20–40% of patients with blunt chest trauma and 20% of patients with penetrating injuries) or tension. Signs of a small pneumothorax on a supine chest radiograph include a deep costophrenic sulcus, basal hyperlucency, a ‘double’ diaphragm, unusually clear definition of the right cardiophrenic angle or left cardiac apex and visualization of apical pericardial fat tags. CT is more sensitive than plain film radiography.

2. Haemothorax – in 25–50% of patients with blunt chest trauma and 60–80% of patients with penetrating wounds.

Lung

1. Contusion – non-segmental alveolar opacities which resolve in a few days.

2. Laceration – a shearing injury results in a parenchymal tear that may fill with blood or air and result in a rounded opacity. Usually resolves spontaneously.

3. Haematoma – usually appears following resolution of contusion. Round, well-defined nodule. Resolution in several weeks.

6. Pulmonary oedema – following blast injuries or head injury (neurogenic oedema).

7. Acute respiratory distress syndrome – widespread air-space shadowing appearing 24–72 hours after injury.

8. Fat embolism – 1–2 days post-trauma. Resembles pulmonary oedema, but normal heart size and pleural effusions are uncommon. Resolves in 1–4 weeks. Neurological symptoms in up to 85% and skin abnormalities in 20–50%.

Diaphragm

Rupture – in 3–7% of patients with blunt and 6–46% of patients with penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma. Diagnosis may be delayed for months or years. Plain film findings include herniated stomach or bowel above the diaphragm, pleural effusion, a supradiaphragmatic mass or a poorly visualized or abnormally contoured diaphragm. Probable equal incidence on both sides but rupture of the right hemidiaphragm is less easily diagnosed.

Mediastinum

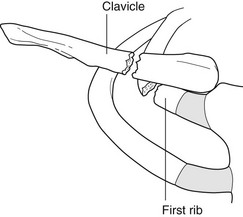

1. Aortic injury – 90% of aortic ruptures occur just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. The majority of patients with this complication die before radiological evaluation, especially when rupture involves the ascending aorta. Plain film radiographic abnormalities of aortic rupture are:

(a) Widening of the mediastinum (sensitivity 53–100%; specificity 1–60%).

(b) Abnormal aortic contour (sensitivity 53–100%; specificity 21–42%).

(c) Tracheal displacement to the right (sensitivity 12–100%; specificity 80–95%).

(d) Nasogastric tube displacement to the right of the T4 spinous process (sensitivity 9–71%; specificity 90–96%).

(e) Thickening of the right paraspinal stripe (sensitivity 12–83%; specificity 89–97%).

(f) Depression of the left mainstem bronchus > 40° below the horizontal (sensitivity 3–80%; specificity 80–100%).

(g) Loss of definition of the aortopulmonary window (sensitivity 0–100%; specificity 56–83%).

2. Mediastinal haematoma – blurring of the mediastinal outline. 80% of mediastinal haematoma is due not to aortic rupture but to other large or small vessel bleeding.

3. Mediastinal emphysema (see 4.30).

Bocchini, G., Guida, F., Sica, G., et al. Diaphragmatic injuries after blunt trauma: are they still a challenge? Reviewing CT findings and integrated imaging. Emerg Radiol. 2012; 19:225–235.

Desai, S. R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: imaging of the injured lung. Clin Radiol. 2002; 57:8–17.

Peters, S., Nicolas, V., Heyer, C. M. Multidetector computed tomography-spectrum of blunt chest wall and lung injuries in polytraumatized patients. Clin Radiol. 2010; 65:333–338.

4.38

Drug-induced lung disease

Diffuse alveolar opacities

1. Pulmonary oedema – cocaine, cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C), heroin overdose, interleukin 2, morphine overdose, OKT3 (in association with fluid overload), some sympathomimetics, salicylate overdose and tricyclic antidepressant overdose.

2. Pulmonary haemorrhage – anticoagulants and those drugs which produce an idiosyncratic thrombocytopenia, crack cocaine, penicillamine and quinidine.

Diffuse interstitial opacities

1. Acute interstitial reactions – methotrexate, nitrofurantoin, procarbazine and drugs causing pulmonary oedema.

2. Chronic interstitial reactions – cytotoxic agents (BCNU, bleomycin, busulphan, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and mitomycin C).

3. Non-cytotoxic agents – amiodarone, gold salts and nitrofurantoin.

Erasmus, J. J., McAdams, H. P., Rossi, S. E. High-resolution CT of drug-induced lung disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002; 40(l):61–72.

Fernández, A. B., Karas, R. H., Alsheikh-Ali, A. A., Thompson, P. D. Statins and interstitial lung disease: a systematic review of the literature and of food and drug administration adverse event reports. Chest. 2008; 134:824–830.

Hagan, I. G., Burney, K. Radiology of recreational drug abuse. RadioGraphics. 2007; 27:919–940.

Müller, N. L., White, D. A., Jiang, H., Gemma, A. Diagnosis and management of drug-associated interstitial lung disease. Br J Cancer. 2004; 91(Suppl 2):S24–S30.

Rossi, S. E., Erasmus, J. J., McAdams, P., et al. Pulmonary drug toxicity: radiologic and pathologic manifestations. RadioGraphics. 2000; 20:1245–1259.

4.39

High-resolution CT – nodules

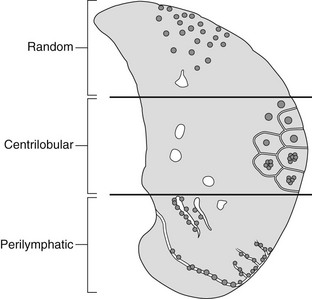

These may be centrilobular, perilymphatic or random.

4.40

High-resolution CT – ground-glass opacification

1. Infective – e.g. Pneumocystis jiroveci, viral.

2. Pulmonary oedema – see 4.12.

4. Diffuse interstitial lung disease – idiopathic or otherwise

(a) Non-specific interstitial pneumonia.

(b) Usual interstitial pneumonia. (NB. Ground-glass opacification less extensive than reticulation.)

(c) Desquamative interstitial pneumonia.

(d) Respiratory bronchiolitis/respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease.

(f) Acute interstitial pneumonia.

(g) Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.

5. Malignancy – diffuse adenocarcinoma (previously bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma).

Hansell, U. D. M., Bankier, A. A., MacMahon, H., et al. Fleischner Society: Glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008; 246:697–722.

Travis, W. D., King, T. E., Bateman, E. D., et al. ATS/ERS international multidisciplinary consensus classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. General principles and recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002; 165:277–304.

Webb, W. R., Müller, N. L., Naidich, D. P. High resolution CT of the lung. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

4.41

High-resolution CT – mosaic attenuation pattern

Mosaic attenuation pattern – small airways disease (constrictive obliterative bronchiolitis)

2. Lower respiratory tract infection – especially viruses but also mycoplasma.

3. Connective tissue diseases – especially rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome.

4. Post-transplantation – heart–lung, heart, bone marrow.

5. Drugs – penicillamine, Sauropus androgynus (Katuk leaves).

Grosse, C., Grosse, A. CT findings in diseases associated with pulmonary hypertension: a current review. RadioGraphics. 2010; 30:1753–1777.

Rossi, A., Attinà, D., Borgonovi, A., et al. Evaluation of mosaic pattern areas in HRCT with Min-IP reconstructions in patients with pulmonary hypertension: could this evaluation replace lung perfusion scintigraphy? Eur J Radiol. 2012; 81:e1–e6.

Sibtain, N. A., Padley, S. P. HRCT in small and large airways diseases. Eur Radiol. 2004; 14(Suppl 4):L31–L43.

4.42

Anterior mediastinal masses in adults

Region I

1. Retrosternal goitre – goitre extends into the mediastinum in 3–17% of cases. On a PA CXR, it appears as an inverted truncated cone with its base uppermost. It is well-defined, smooth or lobulated. The trachea may be displaced posteriorly and laterally, and may be narrowed. Calcification is common. CT shows the connection with the cervical thyroid. Relatively high attenuation compared with other mediastinal structures and other tumours. Uptake by iodine-123 is diagnostic when positive but the thyroid may be non-functioning.

2. Tortuous innominate artery – a common finding in the elderly.

3. Lymph nodes – due to reticuloses, metastases or granulomas.

4. Thymic tumours – are uncommon but occur in 15% of adult patients with myasthenia gravis. They are round or oval and smooth or lobulated. They may contain nodular or rim calcification. If the tumour contains a large amount of fat (thymolipoma) then it may be very large and soft and reach the diaphragm, leaving the superior mediastinum clear.

Region II

1. Germinal cell neoplasms – including dermoids, teratomas, seminomas, choriocarcinomas, embryonal carcinomas and endodermal sinus tumours. More than 80% are benign and they occur with equal incidence to thymic tumours. Usually larger than thymomas (but not thymolipomas). Round or oval and smooth. They usually project to one or other side of the mediastinum on the PA view. Calcification, especially rim calcification, and fragments of bone or teeth may be demonstrable, the latter being diagnostic.

2. Thymic tumours – see above.

3. Sternal tumours – metastases (breast, bronchus, kidney and thyroid) are the most common. Of the primary tumours, malignant (chondrosarcoma, myeloma, reticulum cell sarcoma and lymphoma) are more common than benign (chondroma, aneurysmal bone cyst and giant cell tumour).

Region III (anterior cardiophrenic angle masses)

1. Pericardiac fat pad – especially in obese people. A triangular opacity in the cardiophrenic angle on the PA view. It appears less dense than expected because of the fat content. CT is diagnostic. Excessive mediastinal fat can be due to steroid therapy.

2. Diaphragmatic hump – or localized eventration. Commonest on the anteromedial portion of the right hemidiaphragm. A portion of liver extends into it and this can be confirmed by ultrasound or isotope examination of the liver.

3. Morgagni hernia – through the defect between the septum transversum and the costal portion of the diaphragm. It is almost invariably on the right side but is occasionally bilateral. It usually contains a knuckle of colon or, less commonly, colon and stomach. Appears solid if it contains omentum and/or liver. Ultrasound and/or barium studies will confirm the diagnosis.

4. Pericardial cysts – either a true pericardial cyst (‘spring water’ cyst) or a pericardial diverticulum. The cyst is usually situated in the right cardiophrenic angle and is oval or spherical. CT confirms the liquid nature of the mass.

Drevelegas, A., Palladas, P., Scordalaki, A. Mediastinal germ cell tumours: a radiologic–pathologic review. Eur Radiol. 2001; 11:1925–1932.

Frank, L., Quint, L. E. Chest CT incidentalomas: thyroid lesions, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, and lung nodules. Cancer Imaging. 2012; 12:41–48.

Landwehr, P., Schulte, O., Lackner, K. MR imaging of the chest: mediastinum and chest wall. Eur Radiol. 1999; 9:1737–1744.

Quint, L. E. Imaging of anterior mediastinal masses. Cancer Imaging. 2007; 7(Spec No A):S56–S62.

Takahashi, K., Al-Janabi, N. J. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of mediastinal tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010; 32:1325–1339.

4.43

Middle mediastinal masses in adults

1. Lymph nodes – the paratracheal, tracheobronchial, bronchopulmonary and/or subcarinal nodes may be enlarged. This may be due to neoplasm (most frequently metastatic bronchial carcinoma), reticuloses (most frequently Hodgkin’s disease), infection (most commonly tuberculosis, histoplasmosis or coccidioidomycosis) or sarcoidosis.

2. Carcinoma of the bronchus – arising from a major bronchus.

3. Aneurysm of the aorta – CT scanning after i.v. contrast medium or, if this is not available, aortography is diagnostic. Peripheral rim calcification is a useful sign if present.

4.44

Posterior mediastinal masses in adults

For ease of discussion it can be divided into three regions.

4.45

CT mediastinal mass containing fat

1. Teratodermoid – well-defined soft-tissue mass containing fat and calcification.

2. Diaphragmatic hernia – bowel, liver, kidney or stomach may also be present. Anterior (Morgagni) hernias are usually on the right, and posterior (Bochdalek) hernias usually on the left. Linear soft-tissue densities representing omental vessels help to distinguish hernias which only contain omental fat from pericardial fat pads.

3. Lipoma – relatively rare. Can occur anywhere in the mediastinum.

4. Liposarcoma – can contain calcification, and may also appear as a soft-tissue mass with no visible fat, due to excess soft-tissue component of the sarcoma.

5. Thymolipoma – occurs in children and young adults. Accounts for 2–9% of thymic tumours. Usually asymptomatic.

6. Mediastinal lipomatosis – associated with Cushing’s syndrome, steroid treatment and obesity.

8. Chylolymphatic cyst – fat–fluid level in cyst.

9. Neurofibroma – can have a negative CT attenuation due to myelin content.

4.46

CT mediastinal cysts

(a) Bronchogenic cyst – usually subcarinal or right paratracheal site. 50% homogeneous water density, 50% soft-tissue density due to mucus or milk of calcium content. Occasional calcification in cyst wall, and air in cyst if communicating with airway.

2. Pericardial cyst – usually cardiophrenic angle.

3. Thymic cyst – can develop following radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease.

5. Pancreatic pseudocyst – can track up into mediastinum.

O’Leary, S. M., Williams, P. L., Williams, M. P., et al. Imaging the pericardium: appearances on ECG-gated 64-detector row cardiac computed tomography. Br J Radiol. 2010; 83:194–205.

Peebles, C. R., Shambrook, J. S., Harden, S. P. Pericardial disease – anatomy and function. Br J Radiol. 2011; 84(Spec No 3):S324–S337.

Takahashi, K., Al-Janabi, N. J. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of mediastinal tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010; 32:1325–1339.

Wright, C. D. Mediastinal tumors and cysts in the pediatric population. Thorac Surg Clin. 2009; 19:47–61.

4.47

CT thymic mass

1. Thymoma – occurs in 15% of those with myasthenia gravis (usually occurring in the fourth decade) and 40% of these will be malignant. If malignant it is usually locally invasive and can extend along pleura to involve the diaphragm and even spread into the abdomen. Can contain calcification.

(a) Lymphoid – occurs in 65% of those with myasthenia gravis. Only medulla enlarges and this is not sufficient to be visible on CT.

(b) True hyperplasia – occurs in myasthenia gravis, postchemotherapy rebound, Graves’ thyrotoxicosis, Addison’s disease and acromegaly. Thymus increases in size but is normal in shape.

3. Germ cell tumour – teratodermoid, benign and malignant teratomas.

4. Lymphoma* – thymus is infiltrated in 35% of Hodgkin’s disease but there is always associated lymphadenopathy.

5. Thymolipoma – usually children or young adults. Asymptomatic.

4.48

Ventilation–perfusion mismatch