10 Respiratory system

The history

Breathlessness

Everyone becomes breathless on strenuous exertion. Breathlessness inappropriate to the level of physical exertion, or even occurring at rest, is called dyspnoea. Its mechanisms are complex and not fully understood. It is not due simply to a lowered blood oxygen tension (hypoxia) or to a raised blood carbon dioxide tension (hypercapnia), although these may play a significant part. People with cardiac disease (see Ch. 11) and even non-cardiorespiratory conditions such as anaemia, thyrotoxicosis or metabolic acidosis may become dyspnoeic as well as those with primarily respiratory problems.

Cough

A cough may be dry or it may be productive of sputum.

How long has the cough been present? A cough lasting a few days following a cold has less significance than one lasting several weeks in a middle-aged smoker, which may be the first sign of a malignancy.

How long has the cough been present? A cough lasting a few days following a cold has less significance than one lasting several weeks in a middle-aged smoker, which may be the first sign of a malignancy.

Is the cough worse at any time of day or night? A dry cough at night may be an early symptom of asthma, as may a cough that comes in spasms lasting several minutes.

Is the cough worse at any time of day or night? A dry cough at night may be an early symptom of asthma, as may a cough that comes in spasms lasting several minutes.

Is the cough aggravated by anything, for example allergic triggers such as dust, animals or pollen, or non-specific triggers like exercise or cold air? The increased reactivity of the airways seen in asthma, and in some normal people for several weeks after viral respiratory infections, may present in this way. Severe coughing, whatever its cause, may be followed by vomiting.

Is the cough aggravated by anything, for example allergic triggers such as dust, animals or pollen, or non-specific triggers like exercise or cold air? The increased reactivity of the airways seen in asthma, and in some normal people for several weeks after viral respiratory infections, may present in this way. Severe coughing, whatever its cause, may be followed by vomiting.

Sputum

What does it look like? Children and some adults swallow sputum, but it is always worth asking for a description of its colour and consistency. Yellow or green sputum is usually purulent. People with asthma may produce small amounts of very thick or jelly-like sputum, sometimes in the shape of a cast of the airways. Eosinophils may accumulate in the sputum in asthma, causing a purulent appearance even when no infection is present.

What does it look like? Children and some adults swallow sputum, but it is always worth asking for a description of its colour and consistency. Yellow or green sputum is usually purulent. People with asthma may produce small amounts of very thick or jelly-like sputum, sometimes in the shape of a cast of the airways. Eosinophils may accumulate in the sputum in asthma, causing a purulent appearance even when no infection is present.

How much is produced? When severe lung damage in infancy and childhood was common, bronchiectasis was often found in adults. The amount of sputum produced daily often exceeded a cupful. Bronchiectasis is now rare, and chronic bronchitis causes the production of smaller amounts of sputum.

How much is produced? When severe lung damage in infancy and childhood was common, bronchiectasis was often found in adults. The amount of sputum produced daily often exceeded a cupful. Bronchiectasis is now rare, and chronic bronchitis causes the production of smaller amounts of sputum.

Wheezing

Sometimes stridor (see Ch. 20) may be mistaken for wheezing by both patient and doctor. This serious finding usually indicates narrowing of the larynx, trachea or main bronchi.

The examination

General assessment

An examination of the respiratory system is incomplete without a simultaneous general assessment (Box 10.1). Watch the patient as he comes into the room, during your history taking, and while he is undressing and climbing on to the couch. If this is a hospital inpatient, is there breathlessness just on moving in bed? A breathless patient may be using the accessory muscles of respiration (e.g. sternomastoid) and, in the presence of severe COPD, many patients find it easier to breathe out through pursed lips (Fig. 10.1).

Is there an audible wheeze or stridor?

Is there an audible wheeze or stridor?

Is the patient capable of producing a normal, explosive cough, or is the voice weak or non-existent even when he is asked to cough?

Is the patient capable of producing a normal, explosive cough, or is the voice weak or non-existent even when he is asked to cough?

Is the wheezing audible, usually loudest in expiration, or is there stridor, a high-pitched inspiratory noise?

Is the wheezing audible, usually loudest in expiration, or is there stridor, a high-pitched inspiratory noise?

What is on the bedside table (e.g. inhalers, a peak flow meter, tissues, a sputum pot, an oxygen mask)?

What is on the bedside table (e.g. inhalers, a peak flow meter, tissues, a sputum pot, an oxygen mask)?

What is the physique and state of general nourishment of the patient?

What is the physique and state of general nourishment of the patient?

Respiratory rate and rhythm

The respiratory rate and pattern of respiration should be noted. The normal rate of respiration in a relaxed adult is about 14-16 breaths per minute (Box 10.2). Tachypnoea is an increased respiratory rate observed by the doctor, whereas dyspnoea is the symptom of breathlessness experienced by the patient. Apnoea means cessation of respiration.

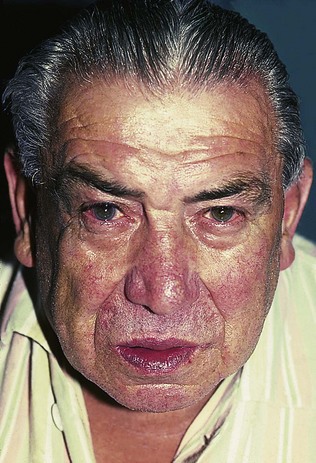

Venous pulses

The venous pulses in the neck (see Ch. 11) should be inspected. A raised jugular venous pressure (JVP) may be a sign of cor pulmonale, right heart failure caused by chronic pulmonary hypertension in severe lung disease, commonly COPD. Pitting oedema of the ankles and sacrum is usually present. However, engorged neck veins can be due to superior vena cava obstruction (SVCO), usually because of malignancy in the upper mediastinum. SVCO can also be associated with facial swelling and plethora (redness).

Examination of the chest

Relevant anatomy

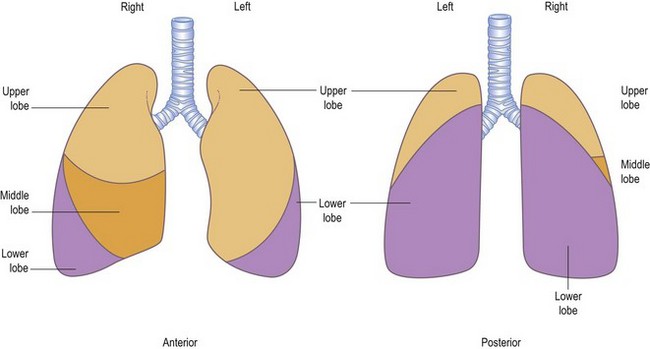

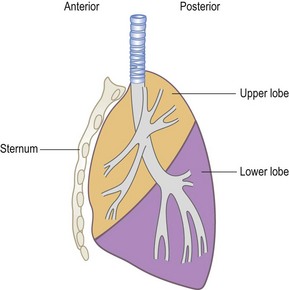

A line from the second thoracic spine to the sixth rib, in line with the nipple, corresponds to the upper border of the lower lobe (oblique or major interlobar fissure). On the right side, a horizontal line from the sternum at the level of the fourth costal cartilage, drawn to meet the line of the major interlobar fissure, marks the boundary between the upper and middle lobes (the horizontal or minor interlobar fissure). The greater part of each lung, as seen from behind, is composed of the lower lobe; only the apex belongs to the upper lobe. The middle and upper lobes on the right side and the upper lobe on the left occupy most of the area in front (Fig. 10.2). This is most easily visualized if the lobes are thought of as two wedges fitting together, not as two cubes piled one on top of the other (Fig. 10.3).

Looking: inspection of the chest

Appearance of the chest

Next, inspect the shape of the chest itself. The normal chest is bilaterally symmetrical and elliptical in cross-section, with the narrower diameter being anteroposterior. The chest may be distorted by disease of the ribs or spinal vertebrae, as well as by underlying lung disease (Box 10.3).

Kyphosis (forward bending) or scoliosis (lateral bending) of the vertebral column will lead to asymmetry of the chest and, if severe, may significantly restrict lung movement. A normal chest X-ray is seen in Figure 10.4. Severe airways obstruction, particularly long-term as in COPD (Fig. 10.5), may lead to overinflated lungs. On examination, the chest may be ‘barrel shaped’, most easily appreciated as an increased anteroposterior diameter, making the cross-section more circular. On X-ray, the hemidiaphragms appear lower than usual, and flattened.

Feeling: palpation of the chest

Swellings and tenderness

It is useful to palpate any part of the chest that presents an obvious swelling, or where the patient complains of pain (Box 10.4). Feel gently, as pressure may increase the pain. It is often important, particularly in the case of musculoskeletal pain, to identify a site of tenderness (Box 10.5).

Feeling: percussion of the chest

The two most common mistakes made by the beginner are, first, failing to ensure that the finger of the left hand is applied flatly and firmly to the chest wall and, second, striking the percussion blow from the elbow rather than from the wrist. The character of the sound produced varies both qualitatively and quantitatively (Box 10.6). When the air in a cavity of sufficient size and appropriate shape is set vibrating, a resonant sound is produced, and there is also a characteristic sensation felt by the finger placed on the chest. Try tapping a hollow cupboard and then a solid wall. The feeling is different as well as the sound. The sound and feel of resonance over a healthy lung has to be learned by practice, and it is against this standard that possible abnormalities of percussion must be judged.

Listening: auscultation of the chest

Listen to the chest with the diaphragm, not the bell, of the stethoscope (chest sounds are relatively high pitched, and therefore the diaphragm is more sensitive than the bell). Ask the patient to take deep breaths in and out through the mouth. Demonstrate what you would like the patient to do, and then check visually that he is doing it while you listen to the chest. If the patient has a tendency to cough, ask him to breathe more deeply than usual, but not so much as to induce a cough with each breath. As with percussion, you should listen in comparable positions to each side alternately, switching back and forth from one side to the other to compare (Box 10.7).

Putting it together: an examination of the chest

Observe the patient generally, and the surroundings.

Observe the patient generally, and the surroundings.

Ask the patient’s permission for the examination, and ensure he is lying comfortably at 45°.

Ask the patient’s permission for the examination, and ensure he is lying comfortably at 45°.

Check the face for anaemia or cyanosis.

Check the face for anaemia or cyanosis.

Inspect the chest movements and the anterior chest wall.

Inspect the chest movements and the anterior chest wall.

Feel the position of the trachea, and check for axillary lymphadenopathy.

Feel the position of the trachea, and check for axillary lymphadenopathy.

Feel the position of the apex beat.

Feel the position of the apex beat.

Inspect the posterior chest wall.

Inspect the posterior chest wall.

Check for cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy.

Check for cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy.

Percuss the back of the chest.

Percuss the back of the chest.

Putting it together: interpreting the signs

If movements are diminished on one side, there is likely to be an abnormality on that side.

If movements are diminished on one side, there is likely to be an abnormality on that side.

The percussion note is dull over a pleural effusion and over an area of consolidation – the duller the note, the more likely it is to be a pleural effusion.

The percussion note is dull over a pleural effusion and over an area of consolidation – the duller the note, the more likely it is to be a pleural effusion.

The breath sounds, the vocal resonance and the tactile vocal fremitus are quieter or less obvious over a pleural effusion, and louder or more obvious over an area of consolidation.

The breath sounds, the vocal resonance and the tactile vocal fremitus are quieter or less obvious over a pleural effusion, and louder or more obvious over an area of consolidation.

Over a pneumothorax, the percussion note is more resonant than normal but the breath sounds, vocal resonance and tactile vocal fremitus are quieter or reduced. Pneumothorax is easily missed.

Over a pneumothorax, the percussion note is more resonant than normal but the breath sounds, vocal resonance and tactile vocal fremitus are quieter or reduced. Pneumothorax is easily missed.

Other investigations

Sputum examination

At the bedside

Hospital inpatients should have a sputum pot which must be inspected (Box 10.8). Mucoid sputum is characteristic in patients with chronic bronchitis when there is no active infection. It is clear and sticky and not necessarily produced in a large volume. Sputum may become mucopurulent or purulent when bacterial infection is present in patients with bronchitis, pneumonia, bronchiectasis or a lung abscess. In these last two conditions, the quantities may be large and the sputum is often foul smelling.

Lung function tests

Simple respiratory function tests fall into three main groups:

1 Measuring the size of the lungs.

2 Measuring how easily air flows into and out of the airways.

3 Measuring how efficient the lungs are in the process of gas exchange.

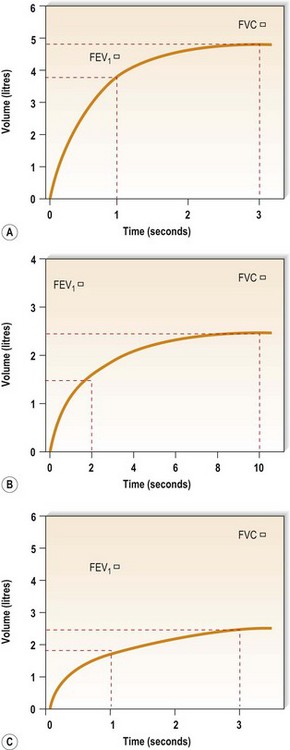

Figure 10.6A shows the trace produced by a spirometer. Time in seconds is on the x-axis and volume in litres is on the y-axis. Thus, the trace moves up during expiration assessing FVC, and along the x-axis as time passes during expiration.

The volume of air breathed out in the first second of a forced expiration is known as the forced expiratory volume in the first second – almost always abbreviated to FEV1. In normal lungs, the FEV1 is >70% of FVC. When there is obstruction to airflow, as in COPD, the time taken to expire fully is prolonged and the ratio of FEV1 to FVC is reduced. An example is shown in Figure 10.6B. A trace like this is described as showing an obstructive ventilatory defect. As noted above, the FVC may be reduced in severe airways obstruction but, in such cases, the FEV1 is reduced even more and the FEV1/FVC ratio remains low.

Some lung conditions restrict expansion of the lungs but do not interfere with the airways. In such individuals, both FEV1 and FVC are reduced in proportion to each other, so the ratio remains normal even though the absolute values are reduced. Figure 10.6C shows a trace of this kind, a restrictive ventilatory defect in a patient with diffuse pulmonary fibrosis.

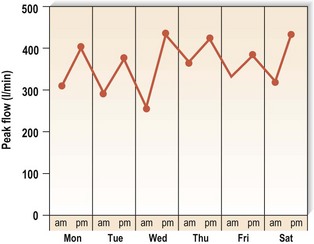

Look again at the normal expiratory spirogram (Fig. 10.6A). The slope of the trace is steepest at the onset of expiration. The trace thus shows that the rate of change of volume with time is greatest in early expiration: in other words, the rate of airflow is greatest then. This measurement, the peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), can be easily measured with a peak flow meter. A simplified version of this device is shown in Figure 10.7. This mini-peak flow meter is light and inexpensive, and people with asthma can use it to monitor themselves and alter their medication, as suggested by their doctor, at the first signs of any fall in peak flow measurement which indicates a deterioration in their condition.

Imaging the lung and chest

The chest X-ray

The chest X-ray is an important extension of the clinical examination (Box 10.9). This is particularly so in patients with respiratory symptoms, and a normal X-ray taken some time before the development of symptoms should therefore not be accepted as a reason for not taking an up-to-date film. In many instances, it is of great value to have previous X-rays for comparison, but if these are lacking then careful follow up with subsequent films may provide the necessary information.

The standard chest X-ray is a posteroanterior (PA) view taken with the film against the front of the patient’s chest and the X-ray source 2 m behind the patient (see Fig. 10.4). The X-ray is examined systematically on a viewing box or computer screen, according to the following plan and referring to the thoracic anatomy described at the beginning of this chapter.

The lung fields

For radiological purposes, the lung fields are divided into three zones:

1 The upper zone extends from the apex to a line drawn through the lower borders of the anterior ends of the second costal cartilages.

2 The mid-zone extends from this line to one drawn through the lower borders of the fourth costal cartilages.

3 The lower zone extends from this line to the bases of the lungs.

The bony skeleton

As well as the standard AP view, lateral views are sometimes carried out to help localize any lesion that is seen. In examining a lateral view, as in Figure 10.8, follow this plan:

Identify the sternum anteriorly and the vertebral bodies posteriorly. The cardiac shadow lies anteriorly and inferiorly.

Identify the sternum anteriorly and the vertebral bodies posteriorly. The cardiac shadow lies anteriorly and inferiorly.

There should be a lucent (dark) area retrosternally which has approximately the same density as the area posterior to the heart and anterior to the vertebral bodies. Check for any difference between the two, or for any discrete lesion in either area.

There should be a lucent (dark) area retrosternally which has approximately the same density as the area posterior to the heart and anterior to the vertebral bodies. Check for any difference between the two, or for any discrete lesion in either area.

Check for any collapsed vertebrae.

Check for any collapsed vertebrae.

The lowest vertebrae should appear darkest, becoming whiter as they progress superiorly. Interruption of this smooth gradation suggests an abnormality overlying the vertebral bodies involved.

The lowest vertebrae should appear darkest, becoming whiter as they progress superiorly. Interruption of this smooth gradation suggests an abnormality overlying the vertebral bodies involved.

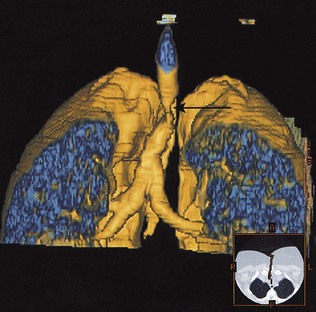

The computed tomography scan

The CT scan is a vital part of the staging of lung cancer, and inoperability may be demonstrated by evidence on CT of mediastinal involvement. CT scanning will demonstrate the presence of dilated and distorted bronchi, as in bronchiectasis. Diffuse pulmonary fibrosis will be shown by a modified high-resolution/thin-section scan technique. Emboli in the pulmonary arteries can be demonstrated by a rapid data acquisition spiral CT technique, and has advantages over isotope lung scanning (see below) in diagnosing pulmonary embolism in patients with pre-existing lung disease. Many scanners can now generate three-dimensional representations of the thoracic structures (Fig. 10.9).

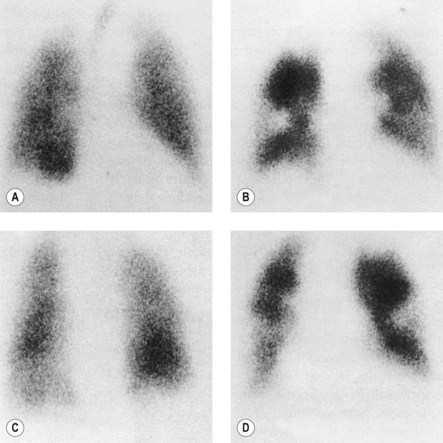

Radioisotope imaging

Blood is usually diverted away from areas of the lung that are unventilated, so a matched defect on both the ventilation and perfusion scans usually indicates parenchymal lung disease. If there are areas of ventilated lung which are not perfused (i.e. an unmatched defect), this is evidence in support of an embolism to the unperfused area. Figure 10.10 shows a ventilation-perfusion isotope scan. The unmatched defects (areas ventilated by the inspired air but not perfused by blood) suggest a high probability of pulmonary embolism.

Flexible bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy is an essential tool in the investigation of many forms of respiratory disease. For discrete abnormalities, such as a mass seen on chest X-ray and suspected to be a lung cancer, bronchoscopy is usually indicated to investigate its nature. Under local anaesthesia, the flexible bronchoscope is passed through the nose, pharynx and larynx, down the trachea, and the bronchial tree is then inspected. Figure 10.11 shows a lung cancer seen down the bronchoscope. Flexible biopsy forceps are passed down a channel inside the bronchoscope, and are used to obtain tissue samples for histological examination. Similarly, aspirated bronchial secretions and brushings of any endobronchial abnormality can be sent to the laboratory for cytological examination.

Pleural aspiration and biopsy

The pleural fluid should also be examined for protein content. A transudate (resulting from cardiac or renal failure) can be distinguished from an exudate (from pleural inflammation or malignancy) by its lower protein content (<30 g/l). Light’s criteria may also be applied (Box 10.10).

Lung biopsy

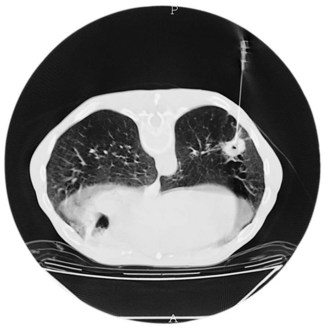

When there is a discrete, localized lesion, it may be possible to obtain a biopsy percutaneously with the aid of CT scanning to direct the insertion of the biopsy needle (Fig. 10.12).

Immunological tests

Asthma attacks may be due to type I immediate hypersensitivity reactions on exposure to common environmental proteins known as allergens. In such individuals, an inherited tendency to produce exaggerated levels of immunogobulin E (IgE) against these allergens is responsible. Part of the assessment of such allergic patients might include skin-prick tests (see Ch. 15). Alternatively, serum levels of specific (individual) IgEs against allergens may be measured by blood tests (formerly known as RAST tests) to demonstrate sensitization. The total IgE level is often raised in patients with asthma, rhinitis or eczema. Delayed (type IV, cell-mediated) hypersensitivity is shown by the Mantoux and Heaf skin tests, used to detect the presence of sensitivity to tuberculin protein. Precipitating immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies in the circulating blood are present in patients with some fungal diseases, such as bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or aspergilloma. In patients suspected of having an allergic alveolitis, IgG antibodies may be demonstrated to the relevant antigens.

Clinical images

Figures 10.13–10.18 illustrate some of the clinical points of this chapter.

Figure 10.14 Chest X-ray showing a right upper lobe mass in a 70-year-old smoker presenting with haemoptysis.

Figure 10.15 Bronchoscopic view of the tumour seen radiologically in Figure 10.14 – histology showed a squamous carcinoma.