Chapter 28 Respiratory system

• Cough: modes of action and uses of antitussives.

• Respiratory stimulants: their place in therapy.

• Oxygen therapy: its uses and dangers.

• Histamine, antihistamines and allergies.

• Bronchial asthma: types, modes of prevention, agents used for treatment and their use in asthma of varying degrees of severity.

Cough

There are two sorts of cough: the useful and the useless. Cough is useful when it effectively expels secretions or foreign objects from the respiratory tract, i.e. when it is productive; it is useless when it is unproductive and persistent. Useful cough should be allowed to serve its purpose and suppressed only when it is exhausting the patient or is dangerous, e.g. after eye surgery. Useless persistent cough should be stopped. Asthma, rhinosinusitis (causing postnasal drip) and oesophageal reflux are the commonest causes of persistent cough. Recently, eosinophilic bronchitis has been recognised as a possibly significant cause; it responds well to inhaled or oral corticosteroid. Clearly the overall approach to persistent cough must involve attention to underlying factors. The British Thoracic Society publishes guidelines on cough and its management that are available online.1

Sites of action for treatment

Cough suppression

Antitussives that act peripherally

Cough originating above the larynx often benefits from syrups and lozenges that glutinously and soothingly coat the pharynx (demulcents2), e.g. simple linctus (mainly sugar-based syrup). Small children are prone to swallow lozenges, so a sweet on a stick may be preferred.

Many of you know that this (simple) linctus used to be very much thicker than it is now, and very likely the thicker linctus was more efficacious. The reason why it was made thinner was this. It was discovered that a large number of children came to the surgery complaining of cough, and they were given the linctus, but instead of their using it as a medicine, they took it to an old woman out in Smithfield, who gave them each a penny, took their linctus, and made jam tarts with it.3

Cough originating below the larynx is often relieved by water aerosol inhalations and a warm environment – the archetypal ‘steam’ inhalation. Compound benzoin tincture4 may be used to give the inhalation a therapeutic smell (aromatic inhalation). This manoeuvre may have more than a placebo effect by promoting secretion of a dilute mucus that gives a protective coating to the inflamed mucous membrane. Menthol and eucalyptus are alternatives. The efficacy of menthol may be explained by the discovery that it can block the ion channel TRPV1, which is activated by capsaicin, the ‘hot chilli’ component of Capsicum species and a potent trigger for cough.

Respiratory stimulants

Uses

• Acute exacerbations of chronic lung disease with hypercapnia, drowsiness and inability to cough or to tolerate low (24%) concentrations of inspired oxygen (air is 21 % oxygen). A respiratory stimulant can arouse the patient sufficiently to allow effective physiotherapy and, by stimulating respiration, can improve ventilation–perfusion matching. As a short-term measure, this may be used in conjunction with assisted ventilation without tracheal intubation (BIPAP5), and thereby ‘buy time’ for chemotherapy to control infection and avoid full tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

• Apnoea in premature infants; aminophylline and caffeine may benefit some cases.

• The manufacturer’s data sheet suggests the use of doxapram for buprenorphine overdoses where the respiratory depression is not responsive to naloxone.

Irritant vapours, to be inhaled, have an analeptic effect in fainting, especially if it is psychogenic, e.g. aromatic solution of ammonia (Sal Volatile). No doubt they sometimes ‘recall the exorbitant and deserting spirits to their proper stations’.6

Oxygen therapy

• High-concentration oxygen therapy is reserved for a state of low PaO2 in association with normal or low Paco2 (type I respiratory failure), as in: pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, pulmonary oedema, myocardial infarction and young patients with acute severe asthma. Concentrations of oxygen up to 100% may be used for short periods, as there is little risk of inducing hypoventilation and carbon dioxide retention.

• Low-concentration oxygen therapy is reserved for a state of low PaO2 in association with a raised Paco2 (type II failure), typically seen during exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The normal stimulus to respiration is an increase in Paco2, but this control is blunted in chronically hypercapnic patients whose respiratory drive comes from hypoxia. Increasing the Pao2 in such patients by giving them high concentrations of oxygen removes their stimulus to ventilate, exaggerates carbon dioxide retention and may cause fatal respiratory acidosis. The objective of therapy in such patients is to provide just enough oxygen to alleviate hypoxia without exaggerating the hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis; normally the inspired oxygen concentration should not exceed 28%, and in some 24% may be sufficient.

• Continuous long-term domiciliary oxygen therapy (LTOT) is given to patients with severe persistent hypoxaemia and cor pulmonale due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (see below). Patients are provided with an oxygen concentrator. Clinical trial evidence indicates that taking oxygen for more than 15 h per day improves survival.

Histamine, antihistamines and allergies

The physiological functions of histamine are suggested by its distribution in the body, in:

• body epithelia (the gut, the respiratory tract and in the skin), where it is released in response to invasion by foreign substances

• glands (gastric, intestinal, lachrymal, salivary), where it mediates part of the normal secretory process

• mast cells near blood vessels, where it plays a role in regulating the microcirculation.

Actions

Histamine acts as a local hormone (autacoid) similarly to serotonin or prostaglandins, i.e. it functions within the immediate vicinity of its site of release. With gastric secretion, for example, stimulation of receptors on the histamine-containing cell causes release of histamine, which in turn acts on receptors on parietal cells which then secrete hydrogen ions (see Gastric secretion, Ch. 32). The actions of histamine that are clinically important are those on:

Blood vessels. Arterioles are dilated, with a consequent fall in blood pressure. This action is due partly to nitric oxide release from the vascular endothelium of the arterioles in response to histamine receptor activation. Capillary permeability also increases, especially at postcapillary venules, causing oedema. These effects on arterioles and capillaries represent the flush and the wheal components of the triple response described by Thomas Lewis.7 The third part, the flare, is arteriolar dilatation due to an axon reflex releasing neuropeptides from C-fibre endings.

Skin. Histamine release in the skin can cause itch.

Gastric secretion. Histamine increases the acid and pepsin content of gastric secretion.

Histamine receptors

Histamine binds to H1, H2 and H3 receptors, all of which are G-protein coupled. The H1 receptor is largely responsible for mediating its pro-inflammatory effects, including the vasomotor changes, increased vascular permeability and up-regulation of adhesion molecules on vascular endothelium (see p. 400), i.e. it mediates the oedema and vascular effects of histamine. H2 receptors mediate release of gastric acid (see p. 528). Blockade of histamine H1 and H2 receptors has substantial therapeutic utility.

Histamine antagonism and H1– and H2-receptor antagonists

The effects of histamine can be opposed in three ways:

• By using a drug with opposing effects. Histamine constricts bronchi, causes vasodilatation and increases capillary permeability; adrenaline/epinephrine, by activating α- and β2-adrenoceptors, produces opposite effects – referred to as physiological antagonism.

• By blocking histamine binding to its site of action (receptors), i.e. using competitive H1-and H2-receptor antagonists.

• By preventing the release of histamine from storage cells. Glucocorticoids and sodium cromoglicate can suppress IgE-induced release from mast cells; β2 agonists have a similar effect.

• histamine H1-receptor antagonists (see below)

• histamine H2-receptor antagonists: cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, ranitidine (see Ch. 32).

The selectivity implied by the term ‘antihistamine’ is unsatisfactory because the older first-generation antagonists (see below) show considerable blocking activity against muscarinic receptors, and often serotonin and α-adrenergic receptors as well. These features are a disadvantage when H1 antihistamines are used specifically to antagonise the effects of histamine, e.g. for allergies. Hence the appearance of second-generation H1 antagonists that are more selective for H1 receptors and largely free of antimuscarinic and sedative effects (see below) has been an important advance. They can be discussed together.

Individual H1-receptor antihistamines

Non-sedative second-generation drugs

Adverse effects

The second-generation antihistamines are well tolerated but an important adverse effect occurs with terfenadine. This drug can prolong the QTc interval on the surface ECG by blocking a potassium channel in the heart (the rapid component of delayed rectifier potassium current, IKr), which triggers a characteristic ventricular tachycardia (torsade de pointes, see p. 442) and probably explains the sudden deaths reported during early use of terfenadine (and prompted its withdrawal from North American markets). It is associated with either high doses of terfenadine or inhibition of its metabolism. Terfenadine depends solely on the 3A4 isoform of cytochrome P450, and inhibiting drugs include erythromycin, ketoconazole and even grapefruit juice. Fexofenadine, the active metabolite, has a much lower affinity for the IKr channel and does not cause QTc prolongation.

Drug management of some allergic states

Hay fever

If symptoms are limited to rhinitis, a glucocorticoid (beclometasone, betamethasone, budesonide, flunisolide or triamcinolone), ipratropium or sodium cromoglicate applied topically as a spray or insufflation is often all that is required. Ocular symptoms alone respond well to sodium cromoglicate drops. When both nasal and ocular symptoms occur, or there is itching of the palate and ears as well, a systemic non-sedative H1-receptor antihistamine is indicated. Sympathomimetic vasoconstrictors, e.g. ephedrine, are immediately effective when applied topically, but rebound swelling of the nasal mucous membrane occurs when medication is stopped. Rarely, a systemic glucocorticoid, e.g. prednisolone, is justified for a severely affected patient to provide relief for a short period, e.g. during academic examinations.8

Bronchial asthma

Asthma affects 10–15% of the UK population; this figure is increasing.

Some pathophysiology

The bronchi become hyperreactive as a result of a persistent inflammatory process in response to a number of stimuli that include biological agents, e.g. allergens, viruses, and environmental chemicals such as ozone and glutaraldehyde. Inflammatory mediators are liberated from mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages. Some mediators such as histamine are preformed and their release causes an immediate bronchial reaction. Others are formed after activation of cells and produce more sustained bronchoconstriction; these include metabolites of arachidonic acid from both the cyclo-oxygenase, e.g. prostaglandin D2 and lipo-oxygenase, e.g. cysteinyl-leukotrienes C4 and D4, pathways. In addition platelet activating factor (PAF) is being recognised increasingly as an important mediator (see Ch. 16, p. 242).

Types of asthma

Approaches to treatment

With the foregoing discussion in mind, the following approaches to treatment are logical:

• Prevention of exposure to allergen(s).

• Reduction of the bronchial inflammation and hyperreactivity.

These objectives may be achieved as follows:

Reduction of the bronchial inflammation and hyperreactivity

Glucocorticoids

(see p. 242) bring about a gradual reduction in bronchial hyperreactivity. They are the mainstay of asthma treatment. The exact mechanisms are still disputed but probably include: inhibition of the influx of inflammatory cells into the lung after allergen exposure; inhibition of the release of mediators from macrophages and eosinophils; and reduction of the microvascular leakage that these mediators cause. Glucocorticoids used in asthma include prednisolone (orally), and beclometasone, fluticasone and budesonide (by inhalation) (see Ch. 35).

Dilatation of narrowed bronchi

β2–Adrenoceptor agonists

The predominant adrenoceptors in bronchi are of the β2 type and their stimulation causes bronchial muscle to relax. β2-Adrenoceptor activation also stabilises mast cells. Agonists in widespread use include salbutamol, terbutaline, fenoterol, eformoterol and salmeterol, and are discussed in Chapter 23. Salmeterol is longer acting because its lipophilic side-chain anchors the drug in the membrane adjacent to the receptor, slowing tissue washout.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists,

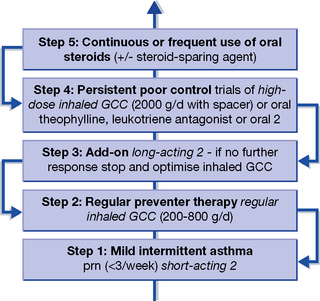

e.g. montelukast and zafirlukast, competitively prevent the bronchoconstrictor effects of cysteinyl-leukotrienes (C4, D4 and E4) by blocking their common cysLT1 receptor. They have similar efficacy to low-dose inhaled glucocorticoid. The scarcity of comparisons with established medications consigns them to a second- or third-line role in treatment. They could be substituted at Step 2 or later stages of the current five-step regimen for asthma (see Fig. 28.1). There are no studies to justify their use as steroid-sparing (far less, replacement) therapy. When used occasionally in this way in patients unwilling or unable to use metered-dose inhalers, serial monitoring of spirometry is essential.

Drug treatment

Constant and intermittent asthma

The 2008 British Thoracic Society guidelines recommend a five-step approach9 (summarised in Fig. 28.1) to the drug management of chronic asthma. The scheme starts with a patient requiring occasional β2-adrenoceptor agonist and follows an escalating plan of add-on anti-inflammatory treatment. Points to emphasise are:

1. Short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists are used throughout as rescue therapy for acute symptoms.

2. Patients must be reviewed regularly as they can move up or down the scheme.

3. Particular attention should be paid to inhaler technique, as this is an important cause of treatment failure. Patients who cannot manage inhaled therapy, even with the addition of a spacer device or use of a dry-powder device, can be given oral therapy, although this will be accompanied by more systemic side-effects.

Anti-inflammatory agents

can commence either with sodium cromoglicate or low-dose inhaled glucocorticoid (Step 2). The inhaled glucocorticoids in current use (beclometasone, budesonide and fluticasone) are characterised by low oral bio-availability because of high first-pass metabolism in the liver (almost 100% for fluticasone). This property is important, as it minimises the systemic effects of inhaled glucocorticoid, 80–90% of which is actually swallowed. Precisely for this reason, prednisolone or hydrocortisone would have less advantage (over oral administration) if inhaled, because they are absorbed from the gut and enter the circulation with relatively little pre-systemic metabolism. Inhaled glucocorticoids also exhibit higher lipid solubility and potency than those usually administered orally. Potency (the physical mass of drug in relation to its effect, see p. 78) is generally unimportant in comparisons of oral drugs, but is essential for locally administered drugs.

Inhaled glucocorticoids

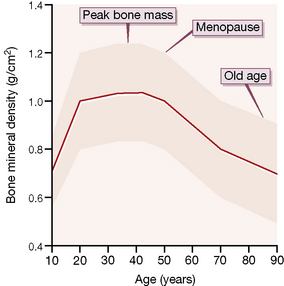

are generally safe at low doses. Topical effects (oral candida and hoarseness) are eliminated by using a spacer device and rinsing the mouth. High doses (> 2000 micrograms/day) are reported to carry a slightly increased risk of cataract and glaucoma; this may reflect local aerosol deposition rather than a true systemic effect. Bone turnover is also increased in adults, suggesting a long-term risk of accelerated osteoporosis, and bone growth may be reduced in children (although evidence indicates that normal adult height can be attained10). Therefore, it is important that patients are maintained on the minimum dose of inhaled glucocorticoid necessary for symptom control.

Acute severe asthma (‘status asthmaticus’)

Immediate treatment

• Oxygen by mask (humidified, to help liquefy mucus). Carbon dioxide narcosis is rare in asthma and 60% can be used if the diagnosis is not in doubt. In older patients, or when there is any concern about chronic carbon dioxide retention, start with 28% oxygen and check that the PaCO2 has not risen before delivering 35% oxygen.

• Salbutamol by nebuliser in a dose of 2.5–5 mg over about 3 min, repeated in 15 min. Terbutaline 5–10 mg is an alternative.

• Prednisolone 30–60 mg by mouth or hydrocortisone 100 mg i.v.

If life-threatening features are present (absent breath sounds, cyanosis, bradycardia, exhausted appearance, PEFR < 33% predicted or best, arterial oxygen saturation of < 92%):

Subsequent management

If the patient is improving, continue:

If the patient is not improving after 15–30 min:

• Continue oxygen and glucocorticoid.

• Give nebulised β2-adrenoceptor agonist more frequently, e.g. salbutamol up to 10 mg/h.

• Add ipratropium 0.5 mg to nebuliser and repeat 6-hourly until patient is improving.

If the patient is still not improving:

• Consider intravenous infusion of aminophylline (0.9 micrograms/kg/min)11 or

• Consider as an alternative intravenous β2-adrenoceptor agonist (as above), e.g. salbutamol 250 micrograms over 10 min, then up to 20 micrograms/min as an infusion (as nebulised salbutamol may not be reaching the distal airways).

• Contact the intensive care unit to discuss intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Treatment in intensive care unit

Transfer (accompanied by doctor with facilities for intubation) is required if:

Treatment at discharge from hospital

• continue high-dose inhaled glucocorticoid and complete course of oral prednisolone

• be instructed to monitor their own PEFR and not to reduce dose if the PEFR falls, or there is a recurrence of early morning dipping in the reading (patients should not generally be discharged until there is less than 25% diurnal variation in PEFR readings).

Warnings

Overuse

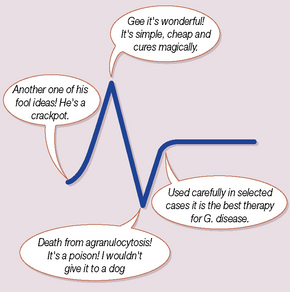

of β2-adrenergic agonists is dangerous. In the mid-1960s, there was an epidemic of sudden deaths in young asthmatics outside hospital. It was associated with the introduction of a high-dose, metered aerosol of isoprenaline (β1 and β2 agonist); it did not occur in countries where the high concentration was not marketed.12 The epidemic declined in Britain when the profession was warned, and the aerosols were restricted to prescription only. Though the relationship between the use of β2-receptor agonists and death is presumed to be causal, the actual mechanism of death is uncertain; overdose causing cardiac arrhythmia is not the sole factor. The subsequent development of selective β2-receptor agonists was a contribution to safety, but a review in New Zealand during the 1980s found that the use of fenoterol (β2 selective) by metered-dose inhalation was associated with increased risk of death in severe asthma,13 and later analysis concluded that it was the most likely cause.14 A further cause for concern comes from a meta-analysis of 19 clinical trials which concluded that long-acting β agonists (LABAs) increased severe and life-threatening asthma exacerbations, as well as asthma-related deaths.15 The US Food and Drug Administration has recently confirmed their belief that the benefits of LABAs still outweigh these risks but have opted for a more cautious labelling policy.16

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Drugs

used to treat COPD are exactly as for asthma, except that antimuscarinics, such as ipratropium or the longer-acting tiotropium, are often more effective bronchodilators than β2 agonists. Patients with reversible airways obstruction should also receive an inhaled glucocorticoid and its combination with a long-acting β2 agonist may improve control, especially in moderate or severe disease (FEV1 < 50% predicted), e.g. fluticasone + salmeterol (Seretide). This strategy is designed to reduce the frequency of disease exacerbations rather than affect the decline in lung function per se.17

Long-term oxygen therapy

improves survival in hypoxic patients. It is indicated when:

• PaO2 is less than 7.3 kPa (56 mmHg) when stabilised on optimal medical treatment.

• PaO2 is 7.3–8.0 kPa and there is evidence of right-sided cardiac failure (cor pulmonale).

• Asthma is characterised by hypersensitivity to the endogenous bronchoconstrictors, acetylcholine and histamine, and by reversible obstruction of the airways.

• Drugs that block the actions of acetylcholine and histamine are weak or ineffective in the treatment of asthma.

• Most anti-asthma treatment is therefore aimed either at reducing release of inflammatory cytokines (glucocorticoids and sodium cromoglicate) or at direct bronchodilatation by stimulation of the bronchial β2-adrenoceptors.

• Aggressive use of glucocorticoids, especially by the inhaled route, is the keystone of the modern stepped approach to asthma management.

• Antihistamines conventionally refer to antagonists of the H1 receptor, and have wide applications in the treatment of allergic disorders, and in anaphylaxis.

• The principal adverse effect of older first-generation antihistamines, sedation, is avoided by use of newer second-generation drugs which do not enter the CNS.

• Smoking cessation and long-term treatment with oxygen are the only interventions that are known to improve survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Devereux G. ABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Definition, epidemiology, and risk factors. Br. Med. J. 2006;332:1142–1144. (the first in a series of 12 weekly articles on the subject)

Hendeles L., Colice G.L., Meyer R.J. Withdrawal of albuterol inhalers containing chlorofluorocarbon propellants. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2007;356:1344–1351.

Holgate S.T., Polosa R. The mechanisms, diagnosis and management of severe asthma in adults. Lancet. 2006;368:780–793.

Irwin R.S., Madison J.M. The diagnosis and treatment of cough. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2000;343:1715–1721.

Kay A.B. Allergy and allergic diseases. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2001;344:30–37. (part I); 109–113 (part 2)

Newoehner D. Outpatient management of severe COPD. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2010;362:1407–1416.

O’Byrne P.M., Parameswaran K. Pharmacological management of mild or moderate persistent asthma. Lancet. 2006;368:794–803.

Plaut M., Valentine M.D. Allergic rhinitis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;353:1934–1944.

Reynolds S.M., Mackenzie A.J., Spina D., Page C.P. The pharmacology of cough. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.. 2004;25:569–576.

Simons F.E.R. Advances in H1-antihistamines. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2004;351:2203–2217.

Weir E.K., López-Barneo J., Buckler K.J., Archer S.L. Acute oxygen-sensing mechanisms. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;353:2042–2055.

1 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2080754/pdf/i1.pdf (accessed 31 July 2010).

2 Latin: demulcere, to caress soothingly.

3 Brunton L 1897 Lectures on the action of medicines. Macmillan, London.

5 Bi-level positive airways pressure. Air (if necessary enriched with oxygen 24% or 28%) is administered through a close-fitting facemask at a positive pressure of 14–18 cmH2O to support inspiration, then at a pressure of 4 cmH2O during expiration to help maintain patency of small airways and increase gas exchange in alveoli.

6 Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689). He was called the ‘English Hippocrates’ due to his classic description of diseases, based on observation and recording.

7 Lewis T et al 1924 Heart 11:209.

8 A man with severe hay fever who received at least one depot injection of corticosteroid each year for 11 years developed avascular necrosis of both femoral heads, an uncommon but serious complication of exposure to corticosteroid (Nasser S M S, Ewan P W 2001 Lesson of the week: depot corticosteroid treatment for hay fever causing avascular necrosis of both hips. British Medical Journal 322:1589–1591).

9 British Thoracic Society 2008 Guidelines on the management of asthma. Thorax 2008;63(Suppl. 4):1–121. Available online at: http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/clinical-information/asthma/asthma-guidelines.aspx [under review at the time of writing] http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/guidelines/asthma-guidelines/past-asthma-guidelines.aspx

10 Agertoft L, Pedersen S 2000 Effect of long-term treatment with inhaled budesonide on adult height in children with asthma. New England Journal of Medicine 343:1064–1069.

11 This intervention is generally safe but not proven to affect outcome. The British Thoracic Society guideline no longer recommends intravenous aminophylline without consultation with a senior physician. Doubtless, this reflects an equal lack of evidence base for benefit and the very clear potential for harm if given to patients already taking oral theophyllines.

12 Stolley P D 1972 Why the United States was spared an epidemic of deaths due to asthma. American Review of Respiratory Diseases 105:833–890.

13 Crane J, Pearce N, Flatt A et al 1989 Prescribed fenoterol and death from asthma in New Zealand: case control study. Lancet i:917–922.

14 Pearce N, Beasley R, Crane J et al 1995 End of the New Zealand asthma mortality epidemic. Lancet 345:41–44.

15 Salpeter S R, Buckley N S, Ormiston T M et al 2006 Meta-analysis: effect of long-acting β agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths. Annals of Internal Medicine 144:901–912.

16 Chowdhury B A, Dal Pan G 2010 The FDA and safe use of long-acting beta-agonists in the treatment of asthma. New England Journal of Medicine 362:1169–1171.

17 A trial in patients without reversibility found that inhaled glucocorticoid had no effect on the decline in their lung function (Pauwels R A, Lofdahl C G, Laitinen L A et al 1999 Long-term treatment with inhaled budesonide in persons with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who continue smoking. New England Journal of Medicine 340:1948–1953).