Chapter 19. Reproductive System

Rationale

Examination of the external genitalia enables screening for common disorders that arise from prenatal development and influences. Examination enables the nurse to detect infections that require further evaluation. Assessment of the reproductive system often provides a beginning point for teaching and discussion related to sexuality and hygiene.

Anatomy and Physiology

Female Genitalia

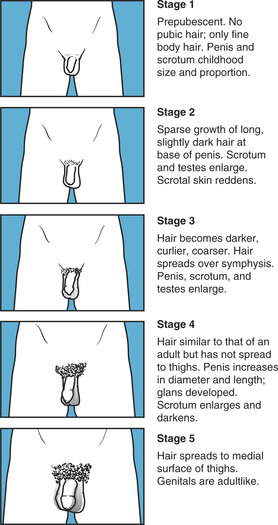

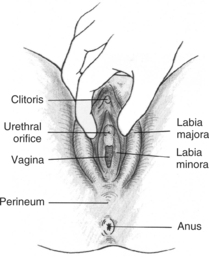

The female genitalia includes the external and internal sex organs. The external sex organs, or vulva, include the mons pubis, a fatty pad overlying the symphysis pubis (Figure 19-1); the labia majora, rounded folds of adipose tissue extending down and back from the mons pubis; the labia minora, two thinner folds of skin medial to the labia majora, which, following prominence in the newborn period, atrophy to become nearly invisible until adolescence; and the clitoris, an erectile body situated at the anterior end of the labia minora. The labia minora are homologous to the male scrotum, and the clitoris to the male penis. Underlying the labia minora is a boat-shaped area termed the vestibule. At the posterior end of the vestibule is the vaginal opening, or introitus, which can be partially obscured by the hymen, a vascular mucous membrane. The perineum is the area between the vaginal opening and the anus. The urethral opening, or urinary meatus, lies between the vaginal opening and the clitoris. On either side of the urethral opening can be seen Skene’s glands, or the paraurethral ducts. Bartholin’s glands, which secrete lubricating fluid during intercourse, are situated on either side of the vaginal opening, but the openings to the glands usually cannot be seen.

|

| Figure 19-1External female genitalia.(From Potter PA, Perry AG: Basic nursing: theory and practice, ed 4, St Louis, 1999, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

The vagina is a hollow tube extending upward and backward between the urethra and the rectum. The cervix joins the vagina, which has a slitlike opening, termed the external os, that provides an opening between the uterus and the endocervical canal. The uterus is a muscular pear-shaped organ suspended above the bladder. In the prepubescent girl the uterus is 2.5 to 3.5 cm (1 to 1.4 in) long, compared with 6 to 8 cm (2.4 to 3.2 in) in the mature woman. The uterine, or fallopian, tubes extend from the uterus to the ovaries and produce a passageway in which ova and sperm meet.

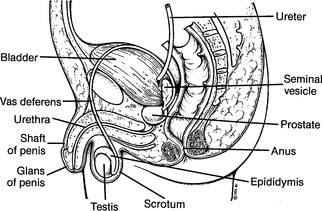

The external male genitalia include the penis and scrotum. The penis consists of a shaft and a glans (Figure 19-2). The shaft is formed primarily of erectile tissue. The glans is a cone-shaped structure at the end of the penis and contains both erectile and sensory tissue. The corona is the crownlike area where the glans arises from the shaft. A loose fold of skin, termed the prepuce or foreskin, overlies the glans. This skin is removed during circumcision. The urethra is within the penile shaft, with the slitlike urethral meatus located slightly centrally at the tip of the glans.

|

| Figure 19-2Male genitalia.(From Whaley LF, Wong DL: Nursing care of infants and children, ed 4, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

The scrotum is a loose, wrinkled sac located at the base of the penis. The scrotum has two compartments, each of which contains a testis, epididymis, and parts of the vas deferens. The testes, epididymis, and vas deferens are considered internal male sex organs.

The testes are ovoid and somewhat rubbery. The testes in the infant are 1.5 cm (0.6 in) long. Testicular length remains virtually unchanged until puberty, when the testes gradually enlarge to the adult length of 4 to 5 cm (1.6 to 2 in). The left testis lies slightly lower than the right. Primary functions of the testis are sperm and hormone production. During ejaculation, sperm drains into the epididymis, and then into the vas deferens before passing into the urethra.

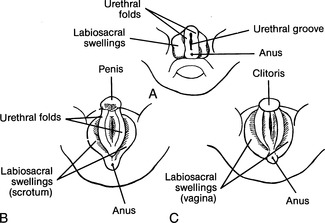

The genetic sex type of the embryo begins during cell division, when X and Y chromosomes are distributed. Initially, internal and external genitalia are not differentiated (Figure 19-3, A). External differentiation begins by about the seventh week of gestation. Under the influence of androgens, enlargement and fusion of primitive urogenital structures occurs and male genitalia are formed (Figure 19-3, B). The testes descend from the abdominal cavity at between 7 and 9 months of gestation. If the tube that precedes their descent fails to close, an indirect inguinal hernia is produced.

|

| Figure 19-3Initial stages in embryonic genital development. A, Undifferen-tiated stage. B, Initial differentiation of external genitalia in male embryo. C, Initial differentiation of external genitalia in female embryo. |

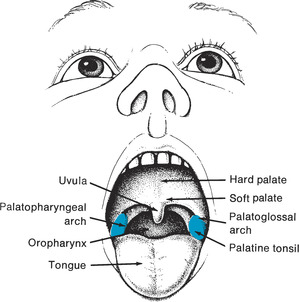

The male reproductive system remains unchanged until maturity. Testicular enlargement is a visible sign of sexual maturation, which can begin by 10 years of age. Accompanying the initial increase in testicular size are a coarsening, reddening, and wrinkling of the scrotal sacs and the growth of a few pubic hairs (the child has no pubic hair). Height and weight increase, and hair growth appears on the face about 2 years after the appearance of pubic hair. During further development the penis enlarges, the voice changes, and body odor appears. The genital skin continues to pigment and the external sex organs continue to enlarge until full maturation is reached. At maturity pubic hair covers the symphysis pubis and medial aspects of the thighs. Reproductive capability accompanies sexual maturity, which is accomplished between 14 and 18 years of age.

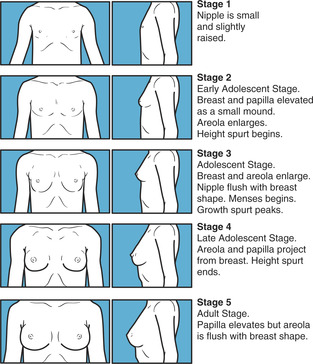

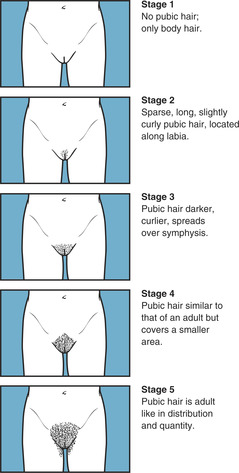

In the embryo, development of female genitalia involves shrinkage and minimal fusion of primitive urogenital structures (Figure 19-3, C). Primordial follicles are formed during the sixth month of gestation, but must wait until puberty for further development. Breast development is usually the first sign of sexual maturation, although growth of pubic hair can precede breast enlargement. The initial pubic hair, located at the sides of the labia, is fine. Gradually the hair coarsens and covers the sides of the labia and the perianal area at full maturation. Internal and external sex organs enlarge. The onset of menstruation provides observable evidence of reproductive maturation (Figure 19-4).

|

|

| Figure 19-4Tanner stages in development of secondary sexual characteristics in females. |

Equipment for Assessment of Reproductive System

▪ Glove for pelvic examination

▪ Drape

▪ Speculum

Preparation

A casual, matter-of-fact approach facilitates examination of the reproductive system. Much of the examination can be accomplished during assessment of the abdomen and anus in the infant and young child. Inform parents (if appropriate) and child of results of the finding as the assessment progresses because this helps relieve anxiety. A child other than an infant should be adequately covered at all times with clothing, such as a top that opens in the front, or a drape. Alternative positions for examination, such as semisitting on the parent’s lap, with the child’s feet on the nurse’s knees, might be more comfortable. An adolescent should be given the option of having a supportive person, such as a friend, present during examination. It is important to ensure privacy and confidentiality and if a parent is present, it must be made clear the adolescent is the patient by directing questions at him or her. It is important to recognize that children and parents from some cultures (e.g., Hispanic) are particularly modest and might require additional assistance to become comfortable.

The first pelvic examination is usually performed when the female child is 18 to 21 years old or as soon as she becomes sexually active, when there is a history of trauma or abuse, when there is vaginal discharge, menorrhagia, primary amenorrhea, secondary amenorrhea for more than 3 months, abdominal pain, or at the adolescent’s request. Adolescents at high risk (sexual intercourse before 18 years, multiple partners, intercourse without a condom, partners with history of intercourse, smoking, sexually transmitted diseases, and absence of three consecutive, negative Pap smears) should be screened yearly.

Inquire whether the female child has had itching, pain on urination, abdominal pain, or vaginal discharge. If the girl is older, inquire whether menses have commenced, the date of the last menstrual period, length of cycle, amount of flow, if the adolescent knows how to or is practicing breast self-examination, dietary and exercise regimen, type of contraception used (if sexually active), number of sexual partners, and experiences with sexual abuse and rape. Inquire about family history of breast cancer and ovarian cancer. If the child has missed three consecutive menses, inquire about eating habits.

Inquire whether the male child has had decreased urination, forced urination, a strong urinary stream, pain on voiding, discharge or drip from the penis, and whether using a condom (if sexually active). Inquire if adolescent knows how or is practicing testicular self-examination.

Assessment of Female Breasts

Assessment is accomplished with the adolescent sitting with arms at her sides. Because the adolescent must disrobe to the waist or wear a front-opening gown, ensure that the room is warm. Privacy is essential. Tell the adolescent that you are going to examine her breasts. A gentle, matter-of-fact approach assists in putting her at ease. If the adolescent is unfamiliar with breast self-examination, this is a good opportunity to explain what is being done and to encourage her to imitate the examination maneuvers. Adolescents might be too embarrassed to touch their breasts, and the nurse’s approach should vary with the patient’s degree of psychologic comfort.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspect the breasts. Note their size, contour, symmetry, and color while the child or adolescent is sitting, trunk exposed, and arms at side. |

Contour and size of the breasts and changes in the areola indicate sexual maturity. Some difference in size of the breasts is usually normal.

One breast can develop before the other, and the adolescent might need reassurance that this is normal.

Clinical Alert

Breast development before 8 years of age can be normal but requires careful assessment.

Delayed breast development (none by age 13 years) should be evaluated along with the development of secondary sexual characteristics.

Dimpling and alterations in the contour of the breast can indicate cancer.

Redness can signal infection.

Striae can be related to obesity or pregnancy. (New striae in the fair-skinned adolescent are red and in the dark-skinned adolescent are ruddy and dark-brown. Old striae in the fair-skinned adolescent are silver and in dark-skinned adolescents are lighter than the skin color.)

|

| Inspect the nipple and areola. Notethe color, size, shape, and the presence and color of any discharge. |

The color, size, and shape of the nipple and areola provide information about sexual maturity.

Nipple inversion is a normal variation and can be present from puberty.

Clinical Alert

Recent inversion, flattening, or depression of the nipple in a more mature adolescent or edema of the nipple or areola can indicate the presence of cancer.

Discharge is an abnormal finding and can be related to a number of hormonal and pharmacologic causes. It should, however, be referred to a physician.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Have the adolescent place her arms above her head, and then on her hips. These maneuvers help accentuate dimpling or retraction that might be missed. Note axilla hair. | African American girls develop axillary hair sooner than Caucasian counterparts (Tanner stages are based on studies of white, English girls) and sometimes before pubic hair. Asian adolescents tend to have finer and sparser hair. |

| Palpate the breast tissue with the patient supine and with her hands behind her neck. If breasts are large, place a pillow under the patient’s shoulder on the side that is to be examined. This distributes the breast tissue more evenly. Use the pads of the fingers flat on the breast to gently compress the tissue against the chest wall. Systematically palpate the entire breast, including the periphery, areola, nipple, and tail using a pattern such as parallel lines, concentric circles, or consecutive clock times, using a rotary motion. During palpation note consistency of tissues and areas of tenderness. If masses are present, note size, shape, consistency, number, mobility, definition, tenderness, erythema, and lymphadenopathy. | Normal young breast tissue has firm elasticity. The stimulation of examination can cause erection of the nipple and wrinkling of the areola. Coolness in the room can also elicit erection of the nipple. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Palpate abnormal masses and note their location (by quadrant or clock), size (in centimeters or inches), shape (round, discoid, irregular, matted), consistency (soft, firm, hard, fluid, cystic), tenderness (whether palpation elicits pain), mobility (fixed or freely movable), definition (well-circumscribed or not), presence of erythema, and lymphadenopathy. |

Clinical Alert

Fixed or movable, hard, irregular, and poorly circumscribed nodules can suggest cancer.

Mobile, nontender, round or disclike, well-delineated nodules can indicate fibroadenoma.

|

Assessment of Female Genitalia

Assessment is best accomplished with the child supine or semireclining. If a young child, the examination can be performed with child semireclining in the parent’s lap; if an adolescent, she might prefer to assume a semisitting position and to have a mirror to see what is taking place. Encouraging the child to keep her heels together provides distraction. Before beginning a pelvic examination, have the adolescent empty her bladder.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspect the mons pubis for hair. Note color, quality, quantity, and distribution of hair, if present. |

Soft, downy hair along the labia majora signals early sexual maturation.

In the mature female, pubic hair forms an inverted triangle.

|

| Inspect the labia majora and labia minora for size, color, skin integrity, masses, and lesions. |

Labia should appear pink and moist.

Clinical Alert

Rash over the mons pubis and labia can indicate contact dermatitis or infestations.

Redness and swelling of labia can indicate infection, masturbation, or sexual abuse.

Fusion of labia can indicate male scrotum.

Labial adhesions can be seen in infants.

Painful, clear, raised vesicles that fuse together to form an ulcer on the genitals are indicative of Herpes simplex.

Hard, nontender, red, sharply demarcated and indurated lesions (chancre) and yellow discharge are indicative of syphilis.

Venereal disease in the young child is a sign of sexual abuse.

Urogenital abnormalities are found in infants born to mothers who used cocaine prenatally.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Note the size of the clitoris. |

Clinical Alert

A clitoris larger than normal can indicate labioscrotal fusion.

In some cultures, female circumcision is practiced, which can produce extensive scarring and adhesions.

|

| Palpate for Skene’s and Bartholin’s glands. |

Skene’s and Bartholin’s glands are normally not palpable.

A small amount of clear, mucousy discharge is normal.

Clinical Alert

If Bartholin’s or Skene’s glands are palpable, infection or cysts might be present.

|

| Inspect urethral and vaginal openings for edema, redness, and discharge. |

Clinical Alert

Redness of the urethra can indicate urethritis.

Hymen tears, enlarged hymenal opening, irregular or thickened hymenal edges, and attenuation of hymenal tissue can indicate abuse.

Redness and foul-smelling discharge from the vagina can indicate a foreign body, infection, sexual abuse, or pinworms.

A white, cheesy discharge from the vagina indicates a candidal infection.

Pregnancy is the most common cause of abnormal bleeding, but bleeding can also be related to foreign bodies, STDs, bleeding disorders, or endocrine disorders.

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding can occur in the absence of these conditions.

Vaginal discharge and dysuria can indicate chlamydial infection.

Refer the child for further examination if a vaginal opening cannot be seen.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Initiate the speculum examination in the adolescent after inspection of external structures. Use a plastic or metal speculum that has been lubricated and warmed with warm water. Usually the narrow Pederson speculum is used.

Initiate the bimanual examination following the speculum examination. Inability to feel ovaries is not unusual, especially if the adolescent is overweight.

|

Clinical Alert

Adnexal tenderness and cervical motion tenderness, as well as tenderness in the lower abdomen, can indicate pelvic inflammatory disease.

|

Assessment of Male Genitalia

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspect the penis for size, color, skin integrity, masses, and lesions. | An obese child might appear to have a small penis because of overlying skin folds. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Note whether the child is circumcised. If uncircumcised and older than 3 years of age, attempt to gently retract the foreskin. Do not forcibly attempt to retract the foreskin; in infants, the prepuce is tight. Forcible retraction can damage the thin membrane and cause adhesions |

The foreskin is normally adherent in children younger than 3 years.

Clinical Alert

A penis that is large in relation to the child’s stage of development can suggest precocious puberty or testicular cancer. An abnormally small penis can indicate a clitoris.

Chancres are indicative of syphilis and need to be reported.

Condyloma acuminatum, or genital warts, is a venereal disease and can indicate sexual activity in an adolescent or sexual abuse in a young child. Warts appear as soft, skin-colored discrete growths that are whitish pink to reddish brown. Warts can be pedunculated or broad based and can enlarge to cauliflower-like masses. Warts on the anus or rectum are associated with anal intercourse.

Small, round or oval, dome-shaped papules with a central umbilicum, from which thick, creamy material can be expressed, are found with molluscum contagiosum.

A foreskin that cannot be easily retracted in a child older than 3 years can indicate phimosis.

|

| Assessment | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inspect the urinary meatus for shape, placement, discharge, and ulceration. If possible, note the strength and steadiness of the urinary stream. |

The urinary meatus is normally slightly ventral at the tip of the penis and slitlike.

Clinical Alert

A urinary meatus that is ventral is called hypospadias. A meatus that is dorsal is called epispadias.

A round meatus can indicate meatal stenosis related to repeated infections.

|

||

| Inspect the quality, quantity, and distribution of pubic hair. Inspect the base of the penis for scratches and inflammation. Inspect the scrotum for color, size, symmetry, edema, masses, and lesions. Palpate the testes by holding a finger over the inguinal canal while palpating the scrotal sac. Cold, touch, exercise, and stimulation cause the testes to ascend higher into the pelvic cavity. A retractile testicle can be pushed back into the scrotum by placing firm pressure on the inguinal canal before palpating the abdomen or genitalia or by having the child sit tailor fashion or blow on a windmill. A retractile testicle can be distinguished from a lymph node by its mobility; it can be massaged down the canal although it will spring back. |

A prepubertal boy normally does not have pubic hair (Figure 19-5). The left testis is lower than the right. A testis should be present in each sac, freely movable, smooth, equal in size, and about 1.5 cm (0.6 in) until puberty. A retractile testis is usually bilateral.

Clinical Alert

The absence of a testis in the scrotal sac can indicate temporary ascent of the testis into the pelvic cavity or an undescended testicle. If the one testis is undescended, the affected hemiscrotum will appear small in contrast to the other hemiscrotum. Reassess. If testes still cannot be felt, refer the child if older than 1 year. Before 1 year the testicle might descend without intervention. If both testes are undescended, this can indicate pseudohermaphroditism, especially if hypospadias or a small penis is also present. Delayed pubertal changes can indicate chronic illness or abnormalities in the anterior pituitary gland, hypothalamus, or testes.

Scratches and inflammation at the base of the penis can indicate lice. Check for nits on the pubic hair.

|

Pain: related to injury agents.

Altered family processes: related to shift in health status of family member.

Infection: related to trauma, inadequate primary defense, insufficient knowledge to avoid pathogens.

Knowledge deficit: related to normal development, safe sexual practices, breast or testicular self-examination, home contraceptive practices.

Self-esteem disturbance: related to disturbances in body image, role performance, guilt/shame.

Impaired skin integrity: related to excretions, moisture, discharge, abuse.

Impaired tissue integrity: related to mechanical factors.

Sexual dysfunction: related to misinformation or lack of knowledge, vulnerability, psychosocial abuse, physical abuse, altered body structure/function.

Altered sexuality: related to conflicts with sexual orientation or variant preferences.

Fear: related to physical/social conditions, fear of others, separation from support system in potentially stressful situations, knowledge deficit.

Altered parenting: related to physical illness.